Filed under: Capitalism, Community Organizing, Featured, Interviews, The State

After Trump’s electoral victory, artist and theorist Ian Alan Paul wrote a series of theses on both Trump and resistance to him. Now, as both Sheriff Clarke and Joe Lieberman stand ready to take the reigns of the security state amidst the ongoing breakdown of the Trump administration, we wanted to pick Ian’s brain about how things have played out thus far.

IGD: We saw mass shut downs and demonstrations against the Muslim ban, but much smaller protests (which to be clear are still ongoing and should be supported) against the continuing roundups and raids by ICE. Why do you think this is?

“we should struggle to grasp how the desire to suspend the usual order of things resonated so widely, and so spontaneously, and how we might act when a collective desire like this arrives again.”

Ian Alan Paul: I’m unsure if we can so easily decipher why one thing generates the conditions for popular revolt while another does not, whether we’re analyzing a moment in retrospect or trying to predict one in advance. What we can do however is look at these two phenomena and attempt to understand what distinguishes them so we can be more prepared to participate in and make the most of these kinds of uprisings when they do eventually arrive again. I think that anyone interested in radical politics is interested in that thing which doesn’t follow the usual course of history, the unexpected and the unpredictable, that thing that drifts in an anomalous direction and by its very nature does not follow a known or knowable path. As such, a necessary task for us as radicals is to attempt to understand the nuances and complexities of these drifts, to try to map their dynamics and grasp the manifold opportunities they provide us with.

The Muslim ban was first and foremost an anomaly, or what others have at times called an event, an exception to or deviation away from the usual order of things. Anomalies upset routines, systems, relations, habits, and procedures, and create the conditions for something radically otherwise to unfold. They can be distinguished by their intensities and the turbulences they introduce, by the attractions and repulsions that they put into play, by the forms of perception and sensation they render possible, and by their spatial and temporal characteristics.

Anomalies upset time in the sense that while they emerge from a particular history, they also disrupt it by the very fact of their emergence. In this way, anomalies are also themselves a particular kind of time, however fleeting. They are both a cessation of the time of work, of school, and of administration, and the opening of a different kind of time, the time of revolt. Whatever force initially brings an anomaly into existence doesn’t own or control what occurs within the space and time of the anomaly and, as a consequence of this, anomalies always invite and create the conditions for the appearance of new kinds of forces that cannot be entirely anticipated or known in advance.

In the case of the Muslim ban, the anomaly took shape in the mass spontaneous occupations of airports, while the ICE raids failed to produce such anomalous conditions. Perhaps this is because of the ICE raids’ historical continuity across several administrations, or in other words because they were largely already part of the order of things in our world. Perhaps it was because of their dispersion across many different and disparate spaces and times. Whatever the reasons or causes were, we should remain attentive to the ways that something else briefly became possible in those airport terminals. We should reflect upon the way that people were able to perceive something, a fragile opening, together. We should see what kinds of ideological and political divisions were crossed, erased, or made irrelevant in that moment, and what new lines of antagonism were drawn. And ultimately, we should struggle to grasp how the desire to suspend the usual order of things resonated so widely, and so spontaneously, and how we might act when a collective desire like this arrives again.

IGD: A lot of big left groups, such as RefuseFascism, seem to have taken to trying to mobilize people around whatever either much of the Left is doing, such as the “Tax/Science/Climate March,” or simply the latest thing that pops up on the radar, such as protesting the firing of Comey. What do you think about this strategy?

“if we want to be effective as a force, this is a temptation that we need to suppress and in some fashion push back against.”

There is always the temptation to respond to the felt immediacy of the present, and certainly the way that contemporary media is structured by corporate algorithmic news feeds and ceaseless 24-hour news cycles creates the perception that the critical political moment can always be located in the heated and accelerating now. At times, this temptation can be overwhelmingly strong because we live in overwhelming times, and it’s unquestionable that things such as climate change, the refugee and migrant crises, and a myriad number of other pressing concerns demand dramatic and militant responses. However, if we want to be effective as a force, this is a temptation that we need to suppress and in some fashion push back against.

When we become trapped by the necessity of having to respond to every little thing, every new crisis and scandal, every contingency and urgency, we also become trapped within the terrain and temporality of that which we mean to oppose. A necessary part of a radical struggle is the attempt to create different spaces and times that don’t conform to the logic or limits of the world they emerge from. The systems and structures that we seek to destroy also anticipate and incorporate forms of antagonism and opposition, which is what makes capitalism and (neo)liberal democracy so historically resilient. And so, when leftists decide to follow the crowd, so to speak, often they are just playing a game which they have no hope of winning. Participating in political struggles as they’ve already been articulated and defined often implies conceding your most radical imaginaries and demands in advance.

“If we are pressed to always respond and react to the time of the world, we may never find the time to escape it.”

It’s an incredibly difficult task to distinguish between what presents an opportunity for revolt and what does not, and often it requires that we explore situations nearly without direction, but this is needed of us if we desire to be meaningful and effective. This activity requires a kind of intuition, a cultivated feeling of what could possibly be in place of the suffocating capitalist world we were born into. Perhaps it’s a practice of developing a sensitivity to possibility itself, which often is so incredibly curtailed in our imaginations. I realize this is unapologetically utopian, but one of the important roles that radicals have always played is keeping the idea of other worlds alive in the hopes of preserving their eventual possibility.

Additionally, another aspect of the dynamic you’ve described is that capitalism as a system always demands that we speed up, that we produce more, that we always have something to offer and express and contribute, even if that thing we express is dissent or critique or frustration. As such, slowing down, refusing to follow along, can itself be an act of resistance. This is what a strike is, after all: a refusal to follow the clock or the calendar as it presently exists, and as a result to make time for something else. If we are pressed to always respond and react to the time of the world, we may never find the time to escape it.

IGD: Before Trump came into power, we saw a massive prison strike, the #NoDAPL struggle, workplace struggles, riots and uprisings against police, and more. It seems that one of the pitfalls in the current era is that these struggles have now been perhaps swept under the rug in favor of “anti-Trump.” Your thoughts?

“Antagonism is incredibly important, and the way that we organize and aggregate together in various forms of collective negativity should be at the forefront of our minds.”

Antagonism is incredibly important, and the way that we organize and aggregate together in various forms of collective negativity should be at the forefront of our minds. This is paramount not because political struggles can simply be reduced to pure antagonism, but rather because the way we express ourselves negatively also in some fashion determines the forms of affirmation that are subsequently available to us.

The #NoDAPL struggle, the prison strike, the riots against police executions, Black Lives Matter, and a great many other movements create particular kinds of political horizons, each of which is in some way necessary but ultimately insufficient. Of course, people must find ways of revolting and resisting from where they are, and in this way it’s unsurprising that we see diverse forms of struggle emerging constantly. However, if struggles remain isolated and concerned only about the particular battlefield they’ve entered onto, we will remain unable to meaningfully oppose or dismantle the larger global systems of which the aforementioned problems are only singular expressions of.

“In these kinds of movements, radicals often refuse to participate altogether in the interest of preserving some kind of purity or alternatively adopt vanguardist positions which only alienates them from the people they mean to transform and radicalize with their militant actions.”

The benefit of something like a movement against Trump is that it dramatically broadens the scope of the conflict, but this also of course carries along an entirely different set of problems for us. In these larger movements, we often find ourselves needing to coordinate with and act alongside groups that we have significant political and ethical differences with, which too often means that these struggles end up being ineffective and hopelessly liberal in their popular manifestation. In these kinds of movements, radicals often refuse to participate altogether in the interest of preserving some kind of purity or alternatively adopt vanguardist positions which only alienates them from the people they mean to transform and radicalize with their militant actions.

We have to refuse the question of whether we should be investing in popular or particular struggles, and instead continually try to think these things together. Our success, to some degree, depends upon this. How do we find that road in between the particularity of singular struggles and the generality of popular movements? Can we imagine forms of coalition and alliance that don’t become homogeneous and remain radically emancipatory and freeing? Can we envisage forms of collectivity that simultaneously affirm our radical differences and our radical interdependencies? These questions aren’t easy to answer, and I’m not going to pretend that any solution is obviously available to us. These are questions that perhaps we must perpetually ask, again and again, to ensure that we don’t lose our way. A politics of negation or affirmation always requires a we, and this mobile, dynamic, inconsistent, diverse, contradictory we is the basis for that which we mean to collectively destroy and that which we mean to collectively become.

IGD: Right now we are seeing heated town hall meetings in response to the American Health Care Act (AHCA). What are your thoughts on these gatherings? Do you see something deeper and more radical coming out of them, and if so, what do you think that could look like?

“These conflicts that are emerging in town halls across the country are fascinating, largely because we are beginning to see a wide-scale disillusionment with the political system in the United States.”

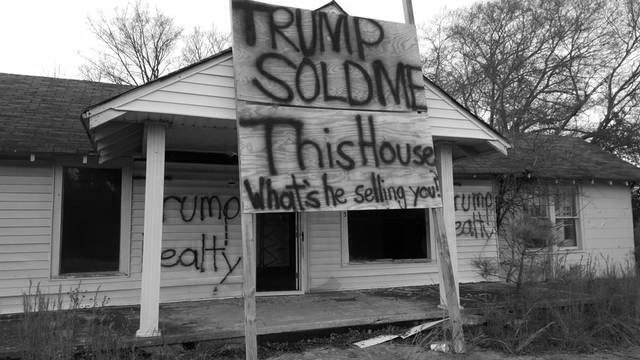

These conflicts that are emerging in town halls across the country are fascinating, largely because we are beginning to see a wide-scale disillusionment with the political system in the United States. Participation in elections continues to fall, which shouldn’t be the least bit surprising given the severe poverty of our political system. The electoral college renders so many people politically irrelevant, which as we saw led to Trump’s victory despite losing the popular vote. Record amounts of dark money are being poured into campaigns big and small, further empowering the wealthy. Gerrymandering and voter disenfranchisement in minority communities continue to become more extreme, reinforcing white democracy. Prisoners are robbed of the right to vote. Why should anyone have a modicum of faith that democracy, as it presently exists in the Unites States, will save them? I think we will continue to see people abandoning electoral politics, and these town hall protests are some of the more visible manifestations of the growing hatred of the political system.

“The important question to ask for us is: as people reject their representatives, what will they turn to instead?”

All of this being said, this is also a dangerous development in many ways. The state won’t simply go away, and as elections continue to lose legitimacy we will likely see the militarization of the police increase as if the two were synchronized. The important question to ask for us is: as people reject their representatives, what will they turn to instead? It isn’t ensured that this radicalization will push people to the left, and we’ve certainly seen far right ethno-nationalist movements become popularized by means of articulating their own critiques of politicians and the state. If the radical left doesn’t provide another choice for these people, I fear that far worse than what we find in our present moment will soon confront us.

IGD: It seems that we’ve entered into a period where we exist both on the edge of a potential uprising, but also in a period where the State is losing more legitimacy every day, and in response is doubling down on repression. People often talk about building autonomy and dual power, but we’re curious if you have seen any concrete examples of this being created, either in North America or across the world?

“I don’t think that we should fool ourselves into believing that the state can be overcome simply by becoming more tactically sophisticated in the streets.”

This is a very important question that requires many sobering answers. Revolutions, revolts, and uprisings are often romanticized, and I think that to some degree they should be, but never at the expense of diminishing the dramatic costs that almost always accompany them. When we look at contemporary examples of mass uprisings, whether in Egypt, Syria, Ukraine, Turkey, Mexico, or elsewhere, they have all been met with the most extreme violence of the state, and no one should deceive themselves into believing that a revolt, no matter how big or militant, will be able to achieve anything but momentary tactical victories over the police or the military in the streets. I’ve lived for extended periods in post-coup Egypt where the military kills with impunity as well as in occupied Palestine where the security apparatus is perhaps most advanced, and I don’t think that we should fool ourselves into believing that the state can be overcome simply by becoming more tactically sophisticated in the streets.

Creating autonomy under capitalism is crucially important and we can see many inspiring examples of this occurring in Southern Europe. Most notably, the thriving municipal movements in Spain have achieved many victories and material gains, but ultimately I think that these can only carry us so far. The form that we should be concentrating most on understanding is the public assembly. Whether in Occupy, or in the Indignados, or in Tahrir, the movements that have focused on taking the space of the city and turning it towards other ends is by far the most interesting thing I’ve seen in my lifetime. The forms of mutual care, of self defense, of radical democracy, and of collective courage together suggest the possibility of exiting the present situation, and we should continue to think about how this particular form can be developed further and experimented with.

“What would it mean to consider putting these forms of infrastructure to different use?”

Ultimately, for the assembly form to be useful, not only would it have to endure for significant durations but it would also have to spread and be contagious, which of course is much easier said than done. Some of the limits that assemblies have faced were defined by police and military assaults, and new forms of militant confrontation will surely be required to be able to fend these off. For the assemblies to be successful as a mechanism of revolution or insurrection, they would also need to have large sections of the police and/or the military either abandon their ranks, or intentionally side with the assemblies, as we saw happen for a very brief period in Egypt in 2011. These different movements would also have to find ways to coordinate and act in solidarity with movements across borders, because it’s also become apparent that a singular revolt in one country, no matter how large, will not succeed if it takes place in isolation. What occurred in the Maidan in Ukraine was incredibly complicated, but one of the lessons we can draw from that revolt is that we should expect other states to militarily intervene when a particular state loses control over its own territory.

There are also of course the radical experiments that have been taking place in the Zapatista communities in Chiapas as well as with the Kurdish autonomous movements in Syria/Iraq/Turkey, but these have largely occurred in geographies that lend themselves to these kind of armed movements and could not so easily be translated to urban settings. Finding ways to link these different forms of struggle, between rural and urban contexts and across continents, is a complex and much-needed endeavor. One of the potential ways forward for these kinds of movements would be to take the question of infrastructure more seriously, which many people have already begun thinking through. We’ve seen very interesting kinds of blockades of airports, of highways, of ports, and of city centers, but perhaps with the exception of the assemblies of the squares they have all limited themselves to the act of refusal. What would it mean to consider putting these forms of infrastructure to different use?

IGD: You wrote, “The crisis has already arrived, and whoever is best able to shape the chaos that ensues will produce what has yet to arrive.” What are your thoughts on Trump’s former cheerleaders, the Alt-Right, and how they have positioned themselves to “shape the chaos” of a post-Trump world?

“As various forms of crises expand, we should expect to see these categories become increasingly militarized as white straight men come to feel they have nothing and everything to lose and act accordingly.”

I don’t think that the Alt-Right is positioned to seize the power of the state or to even have a meaningful influence on it, nor do I think we live in a historical conjuncture defined by the possibility of a slide into fascist politics. If anything, the Alt-Right is perhaps better understood as being an extreme expression of a kind of microfascism that has always been historically endemic to the United States. Their reactionary and authoritarian politics emerge from the steady disintegration of the white heteropatriarchal family structure, from a deepening sense of threatened whiteness and fragile masculinity. As various forms of crises expand, we should expect to see these categories become increasingly militarized and weaponized as white straight men come to feel like they simultaneously have nothing and everything to lose and act accordingly.

Capitalism is deeply structured by racial, gendered, and sexual dimensions, and as the crisis of capitalism expands, these dimensions will also become increasingly policed and repressed. We must take the Alt-Right seriously, particularly as they transform from a dispersed online movement to a coordinated militant movement that seeks to actively confront the radical left. When Trump was inaugurated, I took some solace in the fact that the radical left still largely controlled the space of the streets. In less than four months, that is already no longer the case and I think that should give us all reason to pause. The radical left must be very cautious concerning how we confront the Alt-Right, and should only decide to engage when we’re sure that the odds are significantly tilted in our favor. Refusing to give fascists a platform is important, but engaging in militant confrontations that have little chance of succeeding only encourages and provides experience and training to those we mean to defeat.

“When confronting them we should try to draw together large antifascist coalitions, as has successfully been done in recent decades in Germany and Greece, in order to marginalize these groups as much as possible and in as many fashions as possible.”

When confronting them we should try to draw together large antifascist coalitions, as has successfully been done in recent decades in Germany and Greece, in order to marginalize these groups as much as possible and in as many fashions as possible. In addition, we should resist getting trapped within the confines of a strictly binary struggle, in which organizing within the radical left becomes increasingly concerned only with opposing the Alt-Right. First, we should avoid making the mistake of overestimating the Alt-Right, as they are an incredibly small movement whose members have to travel across the country to organize even small events or demonstrations. Second, our focus must remain on questions of capitalism and the state and on their racial, sexual, classed, and gendered dynamics, which will necessarily entail conflict with groups like the Alt-Right.

If it’s true that the Alt-Right is symptomatic of microfascist tendencies, then it’s best fought not by confronting them directly, as this is ultimately part of what they desire. Only through the production and affirmation of new forms of desire outside of the logic of white heteropatriarchy can we overcome the repressive desires of capitalist society. We must not forget that ethno-nationalists are also fundamentally organized around desire, primarily a love of the powerful, of the self, and of the similar, and as more people’s lives are turned upside down by the crises of the present we must be able to offer them a different form of collective desire that is not repressive in nature but is instead emancipatory.

IGD: If the world is truly becoming more unstable, in this context will things like riots and black blocs then lead to people feeling like they need a strong leader to save them? Is there a way out of this?

“no singular form of organization or method will do everything we need, and we should remain as flexible, experimental, and thoughtful as possible as the situation we’re in develops and proceeds in new directions.”

I think there’s plenty of room for militant struggle in the present, and it should remain a part of how we imagine movements going forward. Of course, there’s also a tendency to fetishize this kind of protest, sometimes to the point where we fail to think at all about why we sometimes use these tactics or when they are and aren’t effective. I also think that now is the time for the invention of new tactics that allow us to gain ground and create novel kinds of collectivities. The beauty of the Black Bloc is that it is not only meant to oppose, but it also allows those who take part to become something else, collectively and anonymously, together. What other kinds of tactics and forms could we imagine doing similar things?

What is sure is that no singular form of organization or method will do everything we need, and we should remain as flexible, experimental, and thoughtful as possible as the situation we’re in develops and proceeds in new directions. As I’ve written elsewhere, I think that the people already most affected by power will also be the ones most ready to confront it, and this should be a starting point for us to think about what it means to try to build a new world together.

“We should not shy away from conflict or from the possibility of destabilization, as these will increasingly arrive on our doorstep whether we’re ready for them or not.”

In the United States, this would imply that we look to the queer-feminist movement, to Black Lives Matter, to the Indigenous and decolonization movements, and to the immigrant movement to begin to understand where we should go from here. Militant radicals have a lot to learn from these movements, and often people in those movements have a lot to learn from radicals who have been participating in various struggles for decades as well.

We should not shy away from conflict or from the possibility of destabilization, as these will increasingly arrive on our doorstep whether we’re ready for them or not. The task for us remains, and will remain, to grasp not only how we can defeat that which is already in the process of destroying the world, but also how we can create a world that is worth living in, a world in which different ways of living are rendered possible, a world that doesn’t resemble our own, a world that would be worth fighting for, cultivating, and defending.

Ian Alan Paul is a transdisciplinary artist, theorist, and curator. His practice encompasses experimental documentary, critical fiction, and media art, aiming to produce novel conditions for the exploration of contemporary politics and aesthetics in global contexts. His projects often incorporate digital/new media, performance, and installation, and are informed by prolonged engagements with continental philosophy and critical/queer/feminist theory. His recent work has approached topics such as the Guantanamo Bay Prison, Fortress Europe, the Zapatista communities, Drone Warfare, and the military regime in post-revolution/post-coup Cairo. Find him on Twitter here.

Ian Alan Paul is a transdisciplinary artist, theorist, and curator. His practice encompasses experimental documentary, critical fiction, and media art, aiming to produce novel conditions for the exploration of contemporary politics and aesthetics in global contexts. His projects often incorporate digital/new media, performance, and installation, and are informed by prolonged engagements with continental philosophy and critical/queer/feminist theory. His recent work has approached topics such as the Guantanamo Bay Prison, Fortress Europe, the Zapatista communities, Drone Warfare, and the military regime in post-revolution/post-coup Cairo. Find him on Twitter here.