Filed under: Analysis, Community Organizing, Mexico, Repression

By Analy S. Nuño

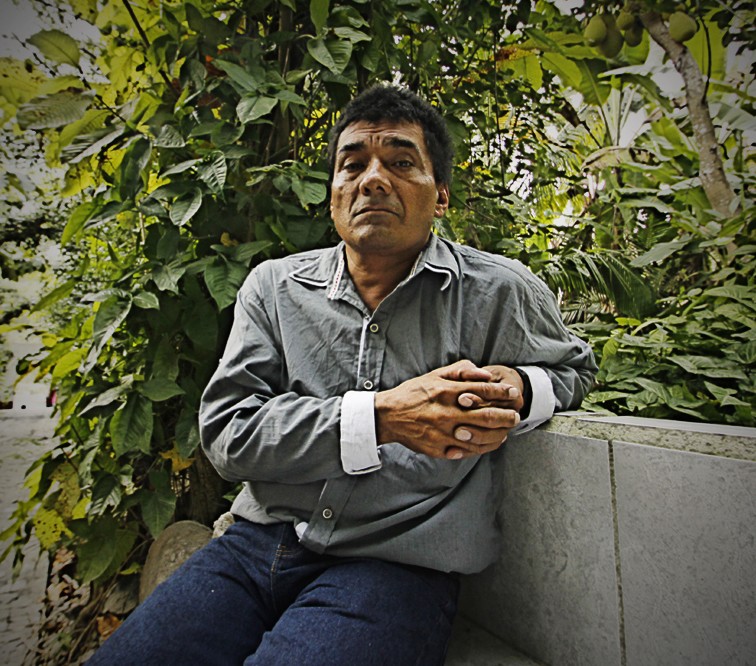

The arrests of social leaders in Michoacán is related to land grabs for resource extraction. Recently freed after four years in prison, Agustín Villanueva — a community police member in Aquila — shares his take on the violence against these communities: First it was the drug trade, but now it’s about mining interests.

AQUILA, MICHOACÁN. In the middle of a dirt road, 90 minutes from the town square, three vehicles meet up and stop. Agustín Villanueva is the first to get out of a white truck, followed by his brother and the group of men that are with them. While the men look on suspiciously, Agustín cautiously greets the crew of the other two cars. He settles in under a tree to take cover from the sun, and — with some reservation — agrees to give an interview, here in the mountains of Michoacan. This mistrust is natural; only 55 days have passed since he was released from prison.

A false accusation of kidnapping kept him, one of the founders of the “autodefensa” community self-defense movement and former president of the town’s communal land council, in prison for four years and two months. He was detained in August 2013, during the first security operation that took place to disarm the autodefensa organizations that took up arms against the Knights Templar cartel.

On that day, eight community members were murdered and 41 more were detained along with Agustín and his brothers Efraín and Vicente. Only the Villanueva brothers remained in prison.

Agustín Villanueva.

– How do you feel?

“I don’t feel very good – they threw me in jail for four years, unjustly and without having committed any crime. I don’t know how to say it, but I feel infuriated and offended by the government. I know that it’s dangerous, in this time and place, to speak of the government in strong or harsh words, seeing how the situation is in Coahuayana, Chinilcuila and Cuelcoman. I don’t feel at ease because what I did, confronting the murderers – the Knights Templar – was the same as what my brothers, my cousins, and my friends did.

– What happened with the Templars?

“Well, the day came when we couldn’t take it anymore, because they charged us protection fees. We were paying protection to a man who called himself ‘Lico’ (Federico Gonzalez, who works for the criminal organization), saying that he was sent by ‘La Tuta’ (Servando Gómez, leader of the group).

They charged us to let us work in our community, on our land, in our mine. They charged protection fees to the women who sold tortillas, the tamarind farmers, the ranchers, they charged us all. We were all under threat, ruined, and nobody wanted to work because what little they made had to be paid up in fees, fees for the Templars — and if you didn’t pay the Templars, then the Jalisco cartel would come, which was another group, worse than the Templars. “What the hell?!” we said, “What is this, anyway?” We couldn’t take it anymore, and so we had to do what we did.”

The year that the Villanueva brothers were imprisoned, the Knights Templar was in control of the mountains and the coast of Michoacan. This situation changed in 2014, when the community members of Santa María Ostula took up arms and succeeded in recovering their territory and expelling the cartel. Agustín did not see the flight of the Templars, however, and although at the time of his release from the Morelia High-Security Social Reintegration Center for High-Impact Crimes he was assured that the town is at peace, he knows that the Aquila mine is an issue that continues to threaten the community, since the royalty fees of over 18,000 pesos a month owed by the Ternium Las Encinas company for the extraction of iron ore, which was agreed upon in a contract from 2012, are not being paid as they should.

The persecution of the leader of the autodefensa group in Aquila began after this agreement, including the fabrication of the crimes that took him to prison. It’s important not to neglect the fact that, if the situation (like with the Templarios) were to be repeated, he represents a significant inconvenience for the mining interests.

– They say that the repression that came down on the other comrades probably had something to do with the mine and with your release, because of the risks posed to the mine by people like yourself and others standing against these processes.

“It’s really dangerous, because this mining company, Ternium, is stealing ore from the community of Aquila. They have permission to make use of 73 hectares and no more, given by the federal government and the community, but they’re converting 383 hectares into a “temporary occupation” mining area, without permission from the community or the federal government. The danger that we’re living under is that the mining company will fabricate charges against anyone who is defending their comrades. They fabricated 12 charges against me, and even though not even one could be proven, they managed to throw me in jail and I was wrongly imprisoned for four years.”

Rising Persecution of Community Leaders

After the Villanueva brothers were released on bail, the persecution and criminalization of leaders of community policing organizations in the Sierra Costa region of Michoacán began to intensify. The most recent strategy employed by the federal and state government to break up the movement is the fabrication of charges for kidnapping, fuel theft, organized crime, money laundering, and terrorism.

A document taped to the door of the Aquila town hall was the only notice that the Federal Attorney General’s Office gave about arrest warrants for Cemeí Verde Zepeda, commander of the community police in Santa María Ostula; Germán Ramírez Sánchez, who was in charge of the Municipal Security group in Aquila, Héctor Zepeda Navarrete, commander of the community police in Coahuayana; José Luis Arteaga Olivares, the mayor of Aquila, and Raúl Baltazar, a community member in Aquila.

In response, the Citizen’s Council for the Security of the Free and United Communities of the Sierra-Costa of Michoacán blocked the highway from Lázaro Cárdenas where it crosses the road leading to Aquila, a place known as Triquis. They demanded an end to this campaign of harassment and false accusations, that the charges be dropped, and demanded a meeting with Berta Paredes, the representative of the Federal Attorney General’s office in Michoacán, and Tania Jacqueline Rangel Villaseñor, an agent of the prosecutor’s office that put together the case files.

“They’re not self-defense organizations, they’re our guardians. The state shouldn’t get involved in disrupting our peace. Really, I fear the state more than the criminals – I don’t want them to come. The statistics show it, we don’t have kidnappings, we don’t have extortion, we don’t have homicides, nothing – but they want to get involved, to take this away just because it suits them.” These were the words of a business owner, a member of the Citizens’ Council, who spoke on condition of anonymity.

Little is known about the case files that led to the arrest warrants that were left on the door of the town hall in mid-November. It’s related to the kidnapping, in February 2017, of five community police from San Pedro Naranjestil, carried out by Marines, who turned them over to the Knights Templar. They were freed, alive, after a mobilization by the communities of Aquila and Coahuayana.

The leaders of the community forces who carried out the rescue, as well as the mayor of Aquila — who at that point denounced the kidnapping of his five police members — are the same individuals who are now facing the kidnapping charges laid out by the Attorney General.

“For rescuing our comrades, they’re rewarding us with arrest warrants,” says Germán Ramirez Sánchez, leader of Municipal Security in Aquila, who is not intimidated by the criminalization and the fabrication of charges against him: “These are very complicated situations, but they don’t diminish the work that we’re doing. We have no low sense of morals, we’re perfectly clear about what we’re doing, and we know it is worth the effort. We don’t have any of the trouble that’s going on in Lázaro, Zamora, in the capital, or in Apatzingan. If none of that is happening here, why are we the bad ones?”

They’re After Natural Resources

For the community members and business owners of Aquila, Coahuayana, Chiniquila, Coalcomán, and Tepalcatepec, the attempts to break up the autodefensa movement through the criminalization of its leaders is, at its core, intended to support the appropriation of natural resources in the Sierra-Costa region of Michoacán. As another member of the Citizens’ Council puts it, “We represent a rural model for security, in which we support and endorse the guys who are defending us. They want to decapitate the movement, and that’s what we’re afraid of, that they’ll leave the movement leaderless, and we won’t have people with the skills and ability to take up arms. They want to disrupt us because they want the beaches, they want the mines, they want all that we have on the coast of Michoacán. Why don’t they let us live in peace?”

The region is rich in mineral, timber, and coastal resources, as well as being a key transit point between the ports of Lázaro Cárdenas, Michoacán, and Manzanillo, Colima. The result has been that the region has been plundered for its natural resources for decades: Clear examples include the illegal logging of valuable lumber such as sangüalica (an endangered species), which has taken place since 2012, when trees were felled throughout the coastal region, to be sent to Chinese and other Asian markets. Further examples include the extraction of materials such as iron, quartz, and other semiprecious stones from the mine in Aquila, the same which was controlled by the Templars for many years.