Filed under: Analysis, Featured, Police, The State, White Supremacy

A look at the George Floyd rebellion in Richmond, Virginia, and how widespread attack of the vestiges of the Confederacy and white supremacy gave way to the creation of communal forms of life. Originally posted here.

Do statues actually matter?

This is a question that left-wing, anarchist, abolitionist, and other rebellious southerners have grappled with in recent years. Some argue that statues don’t affect people’s lives directly; they just represent something symbolic and that getting rid of statues doesn’t have a concrete, material gain for individuals.

This would probably be true if statues were stand-alone, if they didn’t come coupled with the labor and time stolen and put into them, with the histories they invoke (and erase) as well as the histories they help create themselves, and with the surrounding cities that work in tandem with them to achieve certain ideological objectives.

Instead, statues claim both space and time, in their physical construction and in the histories they occupy. They serve as time-capsules, haunted by the past, bringing it forth to spectators in the present.

How might we break the clicking clock in Lee’s coat pocket, and free the past for reclamation?

Richmond’s Statues vs. Richmonders

The Daughters of the Confederacy were founded squarely with the principle that, in fact, monuments did matter for the purpose of trying to resurrect a mythologized history of the Confederacy, and in doing so, perpetuating the “Lost Cause” myth: that the South never had a fighting chance, that they were vastly overpowered by a Northern invading army while just trying to preserve their sovereignty and property rights (for whites to own Blacks), and so they were martyred for their ideals.

This myth also perpetuated the lie that slaves in the American south had been happy with slavery, that slavery was benign, and that slavery had been the best possible thing for a people who were considered by whites to be docile, savage, and immoral. They believed that the ideas from the bourgeois revolutions a century past about human equality and self-determination did not apply to Black people; that Black people could not and would not participate in such revolutions without outside influence, because their humanity was lesser, and therefore void of the same notions of “rights.” This conception of Southernness and whiteness, which views the dead of the Confederacy as martyrs to white southerners alongside the idea that Black people in the United States are too docile and therefore incapable of having their own revolution without outside influence, is a set of ideas that continue to live til this day thanks in part to the memorializing of the Daughters of the Confederacy.

The Daughters of the Confederacy was established thirty-four years after the end of the Civil War in 1896 and spent the decades after funding the erection of Confederate monuments all over the country, particularly the South. To perpetuate their conception of Southernness and whiteness they materialized a revisionist history, in the form of monuments, so that they could create cultural icons around figures of the Confederacy. When a victor wins a war, they construct statues to their icons, and the loser typically does not. But the Daughters of the Confederacy understood that their war would extend well into the future, and so their iconography must as well. Not only did their iconography last many decades, but in recent years, they gained more attention (and in some cases active support) than ever before.

But while the Daughters of the Confederacy were convinced of their mission, and the importance of monuments, we still have to ask ourselves how and why do they really matter today?

The Lee Statue at Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia preceded the Daughters of the Confederacy, and the idea for the statue preceded the idea for Monument Avenue itself. Funding for a Lee statue began being raised in 1870 after Lee’s death and the city began plans for the avenue in 1887, erecting it in 1890. The unveiling drew in one hundred thousand people, and marked Monument Avenue as a place of pilgrimage for those that saw themselves connected to the legacy of the Confederacy. The Daughters of the Confederacy headquarters would eventually be established a few blocks from the end of the avenue, and they helped raise the funds for other statues to be erected on the avenue as well, while simultaneously erecting similar statues across the country.

Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia, was constructed into empty fields past the ends of the existing urban area at the time, on land donated by a land speculator, Otway Allen¹. This area designated in the middle of nothing, where these monuments were designated to be constructed, would go on to be one of the most central streets in an urbanized area in the 20th century. Looking at Monument Avenue this way, it becomes apparent how the myths of the past became integrally intertwined with the daily lives of southerners and their urbanizing environments throughout the 20th century, especially in the case of Richmonders.

In Richmond, the police statue appears to have been covered in red paint. Now it's taped up with trash bags. pic.twitter.com/zaIQ1fu7UV

— Jolene Smith (@aejolene) June 2, 2020

These monuments grew alongside the growing urbanism of the American south, including as more Black people began to move into them after the end of slavery and throughout the Great Migrations, as cities got blacker and blacker while these monuments remained.² Over time the city of Richmond’s civic identity became largely defined by Monument Avenue, and by relation, the “Lost Cause” myth. Otway Allen, the land speculator who donated the land for the Lee statue, would go on to become a Virginia delegate and was seminal in helping pass a constitutional amendment that disenfranchised poor and working class Black Virginians after Reconstruction. This newly strengthened sector of “Lost Cause” civic society was, in part, a reaction against the modest foothold that a coalition of working class Black people had gained in Richmond city government in the 1880’s, during Reconstruction.

But the statues remained well protected, in part because as Richmond urbanized throughout the 20th century, old white money moved in where it felt it rightly belonged, along Monument Avenue. Otway Allen, changed his occupation in the city directory from “farmer” to “capitalist” two years after the construction of the Lee statue, representative of the capitalist class’s shift from plantations and slavery to alliances within manufacturing in the American south and also representative of the shifting gentry who moved into Monument Avenue as it developed. This gentry was set on creating an enclave of old white money on Monument Avenue, as the city of Richmond grew. From its beginning in 1890 every deed on Monument Avenue forbade the sale or lease of any property to Black people. By 1910, 85% of households on Monument Avenue had live-in servants, the vast majority of whom were Black women.³

Heck yes, a marching band is at Marcus-David Peters Circle. pic.twitter.com/Oad2THPMsw

— Goad Gatsby (@GoadGatsby) August 8, 2020

To think that these statues stood alone, disconnected from the experience of daily life in the city of Richmond, would be incorrect. There is an idea from the Situationists called unitary urbanism⁴: that there is a combined effect from the aggregated material forms that urbanism has on those that experience it. That every section of an urban area has a unique combined experience on those who pass through it, because different modes of urbanism work in conjunction: everything from the masonry of a building to how streets are laid out, to the width of the street, to the sign that stops you at the end of the street, to the passing guard that arrests you when you cross the street illegally. All these things taken together have a unified effect on the person going through urban space.

Likewise, Confederate statues grew into the unified urban effect of the American south as its cities developed, and existed in conjunction with new and developing modes of urban control on Black populations in these cities, particularly policing and Jim Crow. The point of Monument Avenue wasn’t just to a communicate a message from the past, the point of Monument Avenue was to become one with the city of Richmond, and to have the city of Richmond itself be that message from the past.

This delivers home the point of the Daughters of the Confederacy, that in speaking from the past, there are white slavery protectors have a right to be lifted up and praised in places like Richmond, in some cases lifted so high above the observer that they are utterly untouchable because of how high off the ground they are. They were placed on those pedestals with the notion that there is a reason that they should be so far from the ground, because of how the future might change the perception of them. The goal was to preserve them indefinitely, not for southerners, but in spite of them.

I grew up in Richmond, and I remember conversations about the statues from a very early age. Monument Avenue was one of the most notable features to outsiders visiting Richmond. But it was always something shameful to many of us.

I remember when I was young, they unveiled an Abraham Lincoln statue down at the waterfront. At the time it was probably the only Union-related statue in the city. I went with my family to see the unveiling of the statue and I remember seeing the first protest I had ever seen there, people holding up cardboard signs shaped like pennies that read “Lincoln wasn’t worth a cent.” Someone flew a plane over the event with a banner that read “Sic Semper Tyrannus,” the words the John Wilkes Booth yelled as he shot Lincoln.

Confirmed: The national headquarters of the Daughters of the Confederacy, in Richmond, VA, the capital of the Confederacy itself, is on fire. https://t.co/XYOVoC7CfN

— Angus Johnston (@studentactivism) May 31, 2020

I remember being surprised at how passionate they were about protesting a president who had died over a century earlier. But they weren’t there to protest Lincoln, but instead to protest the idea of emancipation that they had equated him with. They were there to protest on behalf of the mythology of Southernness and whiteness that the Daughters of the Confederacy worked so hard to preserve in their own statues.

That was one of my earliest political memories.

It was long an accepted fact that the statues on Monument Avenue and the city of Richmond were so intertwined in their legacy, that despite being shameful to many, they weren’t ever going away. Around five years ago that rhetoric started to shift slightly as areas in periphery to Richmond, and Richmond to a lesser extent, had attention paid to Confederate statue removal.

We talked with Maya Little @readkropotkin about how neo-Confederate groups during the Jim Crow South pushed for the construction of statues as a means of white washing the "Lost Cause." But resistance to these symbols of white supremacy – is just as old. https://t.co/RUs3wdlJn4 pic.twitter.com/cBh0JDeHGD

— It's Going Down (@IGD_News) December 21, 2018

There was the battle in North Carolina over the Silent Sam statue which protesters eventually tore down in 2018⁵. And of course, in Charlottesville, discussions within the city council about taking their Lee statue down eventually escalated to the Unite the Right Rally in 2017⁶.

But while these events were playing out in Richmond’s orbit, Richmond remained an untouchable place. “You could take down all the statues in the world, but they aren’t going to come down in Richmond,” was a familiar type of refrain from Richmonders. But if they did come down in Richmond, then surely everything else would start to fall with it.

In the wake of the United the Right Rally, the city of Richmond invited public comments on what to do with the Monument Avenue statues through the Monument Avenue Commission. Despite strong sentiment for removal from many Richmonders, the commission resulted in more shoulder-shrugging from local politicians who pointed out various legal protections established by “Lost Cause” politicians of the past, which prevented their removal.

What You Need to Know About the Nazi Rally in #Charlottesville #Virginia #DefendCville #CharlottesvilleKKK #NoNewKKK https://t.co/dvhs96Ti5w pic.twitter.com/ezVmrzzwXd

— It's Going Down (@IGD_News) August 4, 2017

Throughout all the efforts for removal, wealthy property owners on Monument Avenue continued to argue that the value of their properties were integrally intertwined with the “tourism” and value that the Confederate statues brought to the area. The gentry of Monument Avenue continue to have powerful friends in high places in the city of Richmond, and were fairly successful at obstructing the many of the efforts to get the statues taken down.

So Richmonders, seeing their city not reflecting them, did little things to change it. Throughout the years, Richmonders began attacks on the monuments, throwing paint and engaging in repeated vandalism against them. These attacks cost the city of Richmond thousands of dollars to polish off the statues to maintain the materialized “Lost Cause” mythology. As well, the monuments served as a flashpoint to highlight events elsewhere. After the United the Right Rally, a banner was dropped at the Lee statue in ode to Heather Heyer, killed by fascists in Charlottesville days prior.

The Rupture

But then one night everything changed.

On the second night of the George Floyd uprising in Richmond on May 30th, 130 years and one day after the Lee statue had been unveiled, Richmonders descended upon Monument Avenue in a fury. People who had been told for years they were powerless to change anything about their lives or the city they lived in were all of a sudden encumbered with Herculean strength. They flooded west on Monument Avenue, first approaching the JEB Stuart monument, where people tore away at the iron rebar surrounding it with their bare hands, it as if it were made of cardboard, totally destroying the fencing, and vandalizing the statue in the act.

Police fled in terror as Richmonders stormed westward towards the Lee statue. One police car got caught going eastbound against the Richmonders and to evade sped at nearly 60 miles per hour in their direction as people jumped out of the way. In response, a Richmonder picked up an entire stop sign, pole and sign in all, and one-hand lunged it like an Olympic javelin thrower directly into the front of the police car, perfectly spearing through the front window. The police car continued at full-speed with the sign hanging out of the front of the car.

When the protesters reached the Lee statue, they tore the spotlights out of the ground with their hands and applied the first layer of spray paint of what would become many hundred layers. Richmonders continued on to the headquarters of the Daughter’s of the Confederacy, where the building was attacked and set ablaze. Jefferson Davis’s personal Confederate flag was destroyed in a fire there.

A few days later on June 6th, Richmonders tore down the statue of Williams Carter Wickham, and in doing so tapped into a primal urge in the hearts of Richmonders, to reinvent the city in their vision. From this point on, the attacks on statues were ordinary and ritualistic, as though gravity were knocking them over itself.

Congratulations to demonstrators in Richmond who have apparently just pulled down a statue of Christopher Columbus.

Here's a little background on why someone might do such a thing: https://t.co/wp0qYsuqUD#UntilTheyAllFall pic.twitter.com/J9lOTLSv5U

— CrimethInc. (@crimethinc) June 10, 2020

On June 9th, at a protest for the indigenous of Richmond, Richmonders toppled a Christopher Columbus statue. Richmonders took the statue which appeared to weigh several tons, and rolled it playfully like a child’s bouncy ball down a hill, depositing it in a lake. This was similar to how a slave trader statue in Bristol, of Edward Colston, had been toppled and drowned a few days earlier.

Then the Jefferson Davis Memorial was partially toppled by Richmonders on June 10th, the Howitzer Monument on June 16th, the First Regiment of Virginia Infantry on June 19th.

The Jefferson Davis statue in Richmond has been torn down pic.twitter.com/4njD5TfYq7

— Midwest People's History (@MPHProject) June 11, 2020

Richmonders had done it. They had proven that they could change the city that would never change with their own bare hands. Politicians were helpless and out of sight, booed at every public appearance, hiding like cowards in the shadows from the inhabitants of Richmond. Richmonders had unleashed a wolf within them, bent on Black liberation and Black autonomy.

So the city government, out of their own fears and in the hope of preventing damage to the rest of the statues, magically figured out how to take down the rest of the statues. They filed an emergency injunction, declaring the statues a public safety hazard, because the statues would be taken down by protesters if the city didn’t. This is the most literal example of forcing someone’s hand by Richmonders. As the injunction, triggered by the actions of Richmonders, overruled any legal protections the statues had.

The N. Jefferson side of the Richmond Police Department Headquarters was vandalized over night by protesters. Photo by Regina H. Boone/Richmond Free Press #RichmondVa #RVA #richmondprotest #protest #spraypaint #red #sculpture #art #richmondpolicedepartment #HQ @RichmondPolice pic.twitter.com/UULvqOOulC

— Richmond Free Press (@FreePressRVA) July 26, 2020

The city of Richmond first removed the Richmond Police Memorial on June 11th, the Stonewall Jackson statue on July 1st, two Confederate cannons on July 2nd, then Matthew Fontaine Maury on July 2nd, then JEB Stuart on July 7th, the Confederate Soldiers and Sailors Monument on July 8th, the Fitzhugh Lee Cross on July 9th, the statue of Joseph Bryan on July 9th, at the Virginia State Capitol a smaller statue of Robert E. Lee, busts of Fitzhugh Lee, J. E. B. Stuart, Stonewall Jackson, Joseph E. Johnston, Jefferson Davis and Alexander Stephens, a plaque for Thomas Bocock on July 24th. This doesn’t include the various plaques, statues, and busts removed by various private institutions throughout Richmond in this period. Over an eerie police head statue someone spray-painted a giant “ACAB.”

Removal of Stonewall Jackson statue in Richmond, today: #AP pic.twitter.com/OA8jIu6xW4

— Michael Beschloss (@BeschlossDC) July 1, 2020

Out of anywhere in the world during this uprising, Richmond easily had the most removal of iconography of anywhere.⁷ It was a period of well-justified, and well overdue iconoclasm by Richmonders, a period of ruthlessly stripping away the iconography of the old world which had long haunted them.

In addition to the statue removal, the crowds battled police for months, taking the fight to their headquarters and all over the city, elsewhere. Property was attacked and looted continuously. Two police chiefs resigned in the process. The crowds were disproportionately Black people while other races also participated in the militant actions including white people.

The Reclamation

In honor of Richmond’s own, #MarcusDavidPeters. HE died at the hands of police violence during a mental health crisis. He lives on eternally in our fight for justice. Say his name too as you march. We love you @JusticeforMDP. We’ll get the #MarcusAlert & the CRB. pic.twitter.com/R6s1C1WQm2

— Justice looks like abolition. (@BreRVA) June 6, 2020

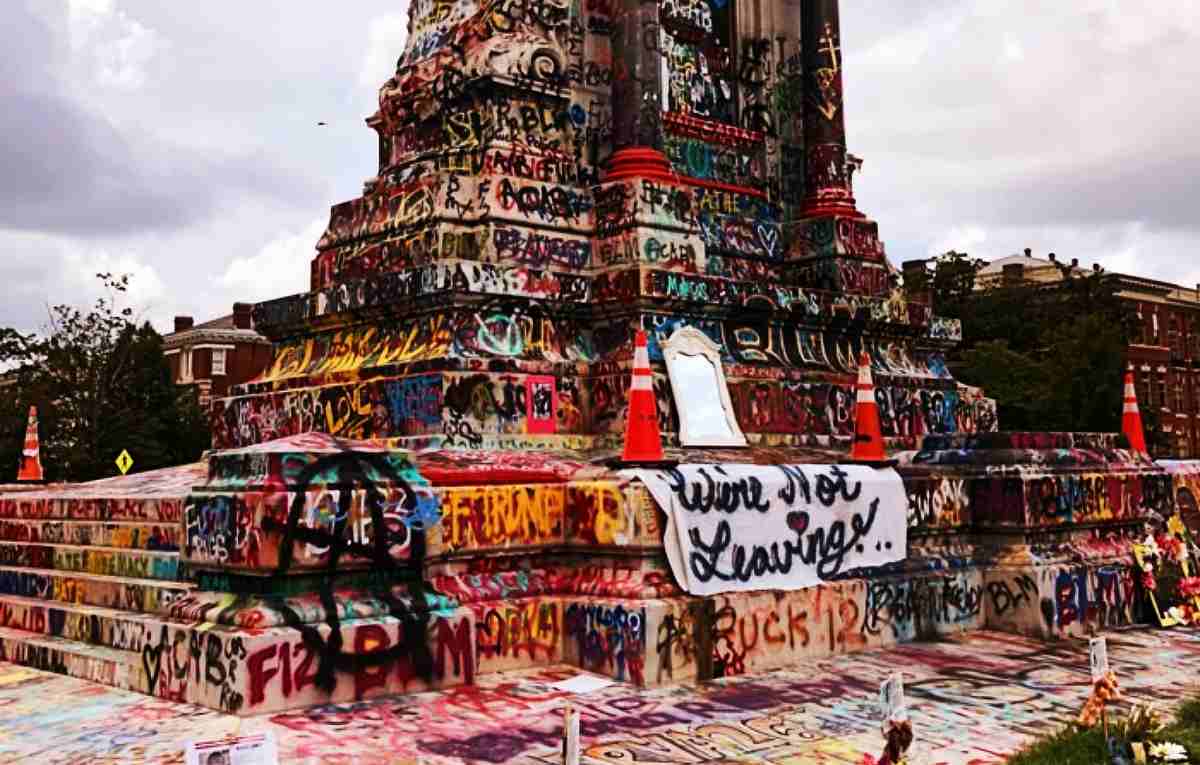

But the reinvention of the city didn’t end there. The Lee statue, once a place of shame, became a meeting place for protesters. It became a base camp where people hosted events, slept overnight, played music and sports. The statue looked nothing like it once had. It was now drenched in the paint of Black autonomous action, drenched so deep that it would be impossible to restore it to its former state.

Every week the paint deepened, making its state the previous week appear bare.

Shreding on Stuart, a difficult spot pic.twitter.com/t3CiGXGFsq

— Goad Gatsby (@GoadGatsby) June 21, 2020

Skateboarders poured concrete and laid wood boards at the base of the JEB Stuart statue so it could be used as a ramp.

There are a few sections that someone improved with some concrete making it more skateable! Love. This. City. pic.twitter.com/lV5WigZvns

— John D. Freyer (@temporama) June 22, 2020

People set up a basketball court on the lawn at the Lee statue.

So glad the hoop is back pic.twitter.com/GZf1YRkae1

— Goad Gatsby (@GoadGatsby) June 26, 2020

They played jazz.

Marcus-David Peters Circle in Richmond, formerly Lee Circle, has become a vibrant community space #13NewsNow #rvaallday #BlackLivesMatter pic.twitter.com/i4MuqCdTTQ

— Stephen Wozny (@woznyphoto) July 3, 2020

They projected Billie Holiday on the statue.

Billie Holiday sings "Strange Fruit" at MDPC. #richmondprotests pic.twitter.com/HrG8sCT75W

— Alex Criqui (@alex_criqui) July 5, 2020

They set up orchestras.

"We Shall Overcome" pic.twitter.com/1eoMnYvTnq

— Jimmie Lee Jarvis (@JLJLovesRVA) July 22, 2020

Sometimes they played solo.

Marcus-David Peter's Circle is one of the most beautiful and special places on earth. pic.twitter.com/ILGJ1IUe0Y

— Alex Criqui (@alex_criqui) November 27, 2020

They established community gardens.

I wanted to post pictures of the garden at Marcus-David Peters Circle on Monday but I got to it now. pic.twitter.com/DXei4rQBXT

— Goad Gatsby (@GoadGatsby) October 2, 2020

And perhaps most importantly, they surrounded the base of the statue with memorials for Black people killed by the police and they renamed the area Marcus-David Peters Circle, named after Marcus-David Peters who was killed by Richmond Police and they renamed the area Marcus-David Peters Circle, named after Marcus-David Peters who was killed by Richmond Police.

Richmonders exorcised the spirit of the Confederacy that haunted their streets for over a century in the form of monuments. But in doing so they also started to imagine what they really wanted their city to look like, a place that fosters community and mutual aid, that values anti-racism and solidarity, that chooses Black liberation, Black autonomy, collective joy and revolutionary play instead of monuments to racists.

forever known as beautiful Marcus David Peters Circle 🖤

sent to us on ig (@/shutitdownrva) pic.twitter.com/bGe74uaUsu

— shut it down RVA! (@MayDayRVA) June 4, 2020

These spaces on Monument Avenue that had long haunted Richmonders were no longer places of a shameful history. Instead they were a history of the present rebellion, a history that was changing everyday. They were a place of pride, a place of rage and passion, and also joy and elation. They attracted far more foot traffic than they had ever before, including from tourists from all over.

At the same time, these were spaces of trauma for protesters, as the Richmond Police Department, Virginia State Police, and the office of Mayor Stoney declared war against them for taking their statues. For months, Richmonders stayed long nights at Marcus-David Peters Circle to prevent eviction by police, and faced brutal and relentless attacks.

At one point a police brutality tracker listed Richmond as second place for the most instances of police brutality per capita within the uprisings from the 2020 summer.

One night included over 200 curfew arrests⁸ (about 1 out of every 1000 people in the city of Richmond), with police searching with rifles under cars and in alleyways for protesters. Richmond Police reported using force on 94 separate incidents throughout the uprising, many of which involved the deployment of dozens of tear gas canisters and flash bangs at each instance.⁹

Incidents/100k residents

1. Portland-61.4

2. Richmond-10.6

3. Seattle -10.3

4. Minneapolis -8.2

5. D.C -6.8

6. DesMoines -5.5

7. Denver -4.7

8. L’Ville -3.8

9. Columbus -2.6

10. Austin -2.0

10. Detroit -2.0

11. LA -1.4

12. NYC -1.3

12. Philly-1.3

13. Chicago-1.1

14. San Jose-1.0— /r/2020PoliceBrutality (@r2020PB) November 30, 2020

As politicians and police worked their hardest to repress and appropriate the struggles for Black liberation in the city of Richmond (of which the statues were only one small part) I can’t help but think of the foresight the Daughters of the Confederacy and those that helped perpetuate the “Lost Cause” myth must have had in conceptualizing their purpose for their successors.

They knew how long the statues would last. They knew to construct them so high and heavy that many of them would be impossible to pull down with rope and hands.

I also think about how there is a legend that a cornerstone of the Lee statue contains a time capsule with one of the only existing photos of Lincoln on his deathbed, which Mary Todd had wished to be destroyed.¹⁰ They knew they were speaking to the future. In building these statues and passing legislation that would preserve them forever, they were playing with the nature of time, making all of Monument Avenue a giant time capsule itself, which would defy their own deaths, and survive long after them.

Where is Time?

The spirit is something that is immaterial that continues to exist in the material world, something that defies time, by projecting the past into the future.

Similarly, dead-labor or dead-time, is the labor that occupies the commodity and capital that are created by it. Labor that was once alienated from those who produced it, but remains still in the commodity form. America as a project, as a colony, is one massive pile of dead-time, the base of which is almost exclusively from African slaves.

The three hundred-year old bricks at the base of some streets in Richmond are not simply bricks, they are also the weeks, days, years, lifetimes stolen from Black people. It is also everything that time represents to a living being, it is self-determination, autonomy, freedom. Slavery and the systems of labor that followed stole all those things and embodied them in material forms.

Within an hour of unconfirmed reports that shots were fired at the Marcus-David Peters Circle, more than 20 cars have formed a perimeter around to protect it and the people inside pic.twitter.com/lBUfMX5Ptq

— Sabrina Moreno (@sabrinaamorenoo) November 1, 2020

But this dead-time, this labor continues to exist today and is foundational to this colony. Sometimes this labor is just a brick, sometimes it is bought and sold many times over for many centuries and no longer resembles its original form.

The statues on Monument Avenue, the city of Richmond, and the colony of America are not just made up of the inanimate, but instead of dead-time. The labor stolen at the expense of Black’s people self-determination and autonomy, continues to live in these objects. These statues reanimate this dead-time, but instead of it being reanimated for Black people, they are reanimated to serve the autonomy of white property owners who weaponize these statues against the Black descendants whose ancestors’ labor they stole.

But in certain moments, this paradigm bursts at its seams. Sometimes Black people in Black revolt declare themselves as the proper owners of that which has been stolen from them. In acts of looting and destruction poor and working class Black people are not just engaging in what white media refers to as senseless nihilism, but instead are engaging in acts that are spiritual and rooted in liberation: by taking back the autonomy stored as dead-time in the commodity-form, and in choosing to use or destroy it, they are truly embracing that autonomy. This idea that Black revolt can engage in this time-hacking and reclaim the primitive accumulation that was stolen from their predecessors, is the absolute kryptonite to the American colony.¹¹ ¹²

Marcus-David Peter's Circle is one of the most beautiful and special places on earth. pic.twitter.com/ILGJ1IUe0Y

— Alex Criqui (@alex_criqui) November 27, 2020

As Walter Benjamin awaited what he saw as inevitable Nazi capture in 1940, before fleeing to Spain and committing suicide, he wrote one final piece, “Theses on the Philosophy of History”, where he lamented the almost religious aspect of Marxists’ historical materialism, which seeks to keep its adherents waiting for the proper moment for change, or rupture, which will happen when the material circumstances are perfect.¹³ ¹⁴ For someone awaiting certain doom by Nazi capture, this was a hopeless vision, as it is a hopeless vision for the millions of people who have perished and anguished due to systems built on white supremacy and colonialism. The idea that “progress is on the way, you just have to be patient and calm down” continues to be invoked in various liberal and leftist iterations.

Benjamin goes further with his critique, and says the problem of historical materialists is viewing the past as something that remains linear after each moment passes by, and in doing so they view the past as a series of events; a progress. Instead, Benjamin invokes the painting Angel Novus by Paul Klee as a metaphor to explain how history is actually viewed. The painting features an angel facing the viewer and seemingly drifting backwards.

A Klee painting named ‘Angelus Novus’ shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing in from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such a violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.

Benjamin suggests that the fault of historical materialists is that their conception of a progress of history is from a warped perspective, in that history is defined by victors, in a series of successions from the last. While we should view history like the angel drifting backwards, seeing the piles of rubble stack on top of one another in the distance as time passes, with those who did not reach redemption in their lifetimes lost in the wake.

There is no inevitable progress of history, it is an optical illusion, and instead, the present is what you make of it.

Rather than waiting for a revolutionary future to save us, we instead have to engage in revolutionary action which save this past in our present, and therefore the perfect time for action is now!

When we do this, we change our whole view of history from our angle. In doing so we are engaging in an odd sort of time travel, in which time itself ruptures and stops, and the past leaps forward into the present and is redeemed. This is a reclaiming of the past, it is a messianic time, and a rupture in our way of understanding space-time.

This is precisely what happens when a statue commemorating those who fought for slavery, built by the wealth stolen through slavery, is transformed into a space of community and joy by the descendants of the enslaved in a single night. In the moments of destruction and appropriation of these monuments, every moment of despair and anguish as those Black Richmonders in the past have looked upon those statues, is called forth instantly, to be redeemed in the present.

Afterword

In January 2021, the State of Virginia reclaimed the statue, building large heavy-duty fences around it to prevent people from forming community there. They said it was to prepare to take down the statue, but that was six months ago.

As the state attempts to take back reclaimed space, it is no coincidence that politicians attempt to take back reclaimed history as well.

Mayor Stoney recently published a New York Times article in which he wrote an utterly false tale about how he led efforts to take down the statues, and how the police violence was an accident along the way.¹⁵ That may be the only New York Times article profiling the timeline of events in Richmond that exists, and so Stoney’s revisionist history will likely shape how outsiders understand what happened in Richmond in the summer of 2020.

I wrote this so that a history of these protesters and their uprising may be preserved. This was an unprecedented revolt for Black liberation and Black autonomy.

No politician aided it.

The efforts of politicians to take back this history while police take by physical space show how they view this reclaimed space-time as a threat to their very existence. Unfortunately, they currently continue to lay claim to these.

Yet still…

The present remains unwritten.