Filed under: Action, Solidarity, Southwest, Uncategorized, War

A report on the encampment at Arizona State University (ASU) in so-called Tempe, Arizona. Originally published on Living and Fighting.

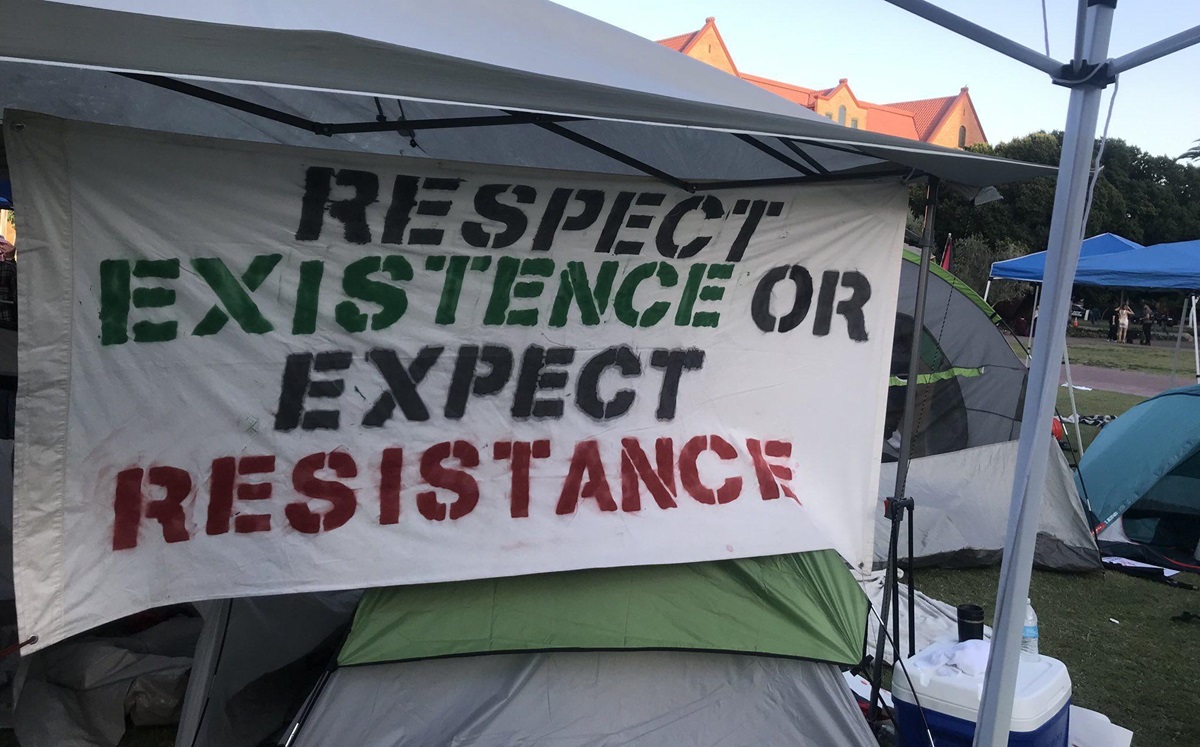

A comrade and I arrived at Arizona State University around 11 am on Friday, April 26, hoping to witness, support, and participate in the campus occupation in solidarity with the people of Gaza. We arrived to find a densely clustered collection of tents on the lawn of ASU’s Old Main building, surrounded by about 100 people chanting, singing, and drumming their expressions of solidarity with Palestinians and their condemnations of the Israeli state. Across from the protesters, blocking a lane of traffic on University Drive,was a similarly dense cluster of a dozen Tempe and ASU police cars. Their red and blue sirens flashed as the officers looked on at the nascent occupation, which they had failed to crush earlier that morning.

“We began around 8:30 this morning,” one camp occupant told me. “Around forty people pretty quickly set up tents on the lawn. After about fifteen minutes, a landscaper called someone–either school administration or the cops–and it took maybe five or ten minutes for the cops to show up.” While we found a quieter space away from the encampment to have our conversation, a faint echo of chants still found its way to us.

“The initial police response was eight squad cars total–four on either side of the encampment and they pretty much immediately escalated,” the occupier continued, “They arrested two or three people in the confrontation and started pulling down the tents.” Despite the shockingly quick escalation from the police, the participants were able to regroup, link arms, reclaim their tents from the pile the police had made of them, and begin setting them back up. It was around this time that the police and ASU turned on the sprinklers, presumably in an attempt to humiliate, antagonize, and otherwise further crush the morale and resolve of the protesters. Instead, the sprinkler situation was quickly remedied with a bit of quick thinking and creativity: five-gallon water jugs–proving their utility in this movement for at least the second time–were placed over the sprinkler heads.

“This action came together really fast without a lot of planning,” said the camper. “It began with this week of events on campus called The Liberation School, where they talked about ASU’s investments in the military-industrial complex as well as [ASU President] Michael Crow’s involvement with the CIA, and all of the different ways that ASU and Israel are tied together.” The week after that was when the campus occupations kicked off across the country. When that happened, a coalition of student groups–like the Party for Socialism & Liberation , Democratic Socialists of America , Revolutionary Communists of America , and a few different Palestinian student groups–called Students Against Apartheid joined with Students for Justice in Palestine and pieced this occupation together.

A Rupture of Daily Life

After that morning’s initial confrontation, a fragile sense of stability developed that lasted well into the night. The day took on a certain rhythm as participants maintained a near-constant stream of chants and drumming, punctuated by novel moments that would soon become ritualistic: a counter-protester would attempt to instigate a fight before being de-escalated, an announcement made, a speech or poem shared, an organizer would urge participants not to antagonize the police or counter-protesters. Some of the Muslim students were members of a nearby mosque, and this led to a steady stream of material support that trickled into the camp, including chicken shawarma sandwiches. The five daily Salah were held at the encampment and, after the Friday afternoon prayers at the mosque, numbers at camp roughly doubled as attendees arrived together.

A space of opportunity and possibility opened itself up before us: daily life had ruptured–even if only a little bit–and in our departure from our quotidian lives we found ourselves stunned to have made it this far, and by the chances of the moment. That said, we could accomplish little more than to chant at the encampment and wait, while the cops lurked along the edges and a police drone hovered overhead, its whirring motors just audible over the ceaseless energy of camp.

As the sun set and night fell, the stasis remained. Numbers remained steady, as did the hesitating optimism that had carried through the warmth of the day. But as darkness settled in, the police made preparations to clear the camp. Through a window at Durham Hall–a building adjacent to the Old Main lawn–protesters could see Tempe and ASU police using one of the classrooms to brief one another and strategize. Down the block on College Avenue, the police started staging patrol cars and buses. Before long, rumors of an eviction circulated among the protesters and a faculty member alerted the camp that the police planned to sweep it at 11 p.m. Around 10:30 p.m., the police declared the camp an unlawful assembly and ordered its dispersal. By 11 p.m., as had been rumored, the police started to make arrests. Quickly, those present split into two groups: occupants that couldn’t or didn’t want to risk arrest moved together to the sidewalk and looked on as those who wanted to try and hold the space in its waning moments sat, arms locked together, as the police pulled them apart and arrested them one by one. At least sixty-nine people were arrested by the end of the night.

The Next Encampment

“I’m pretty happy with how it all went, despite not lasting through the night,” one protester told me when I spoke to them the following day. “A lot of people sort of expected it wouldn’t but despite that, I think it was successful. [The camp] got so much material support and community support and so many people stopped by throughout the day and night. My biggest criticism is that [the organizers] didn’t have a cohesive plan to either protect the encampment or to disperse and regroup, rather than linking arms and locking down.”

The protester suggested that it was an oversight to “bring all of their supplies–all of their food, all of their tents–into the encampment, just for it all to be thrown away by the cops in one night, even though the amount of supplies could have probably sustained a multi-day encampment.” This protester also remarked on instances throughout the day when certain people in the camp would chastise others for being disrespectful to the police, and remarked specifically on one of the chants heard on Friday: “Peaceful protest, peaceful arrest.”

“Apparently, they were actually supposed to be chanting, ‘peaceful protest, no arrest,’ but I think that kind of shows the mindset some people were going into this with.” The chant was indicative of a liberal nonviolence that seeks to control, contain, and limit the confrontational capacity of social movements, as well as the agency of individuals acting within them.

“There definitely needs to be a broader tactical approach that’s more conflictual and antagonistic and maybe something like that will develop through more experience,” they continued. “I think there’s a lot of potential here still: there’s a lot of support for it and despite how unsure, uncertain and inexperienced a lot of the people there were, there was a huge amount of passion, and that passion is really the most important thing you need to start these struggles.”

Friday’s repression is the largest mass arrest of a social movement in the Phoenix metropolitan area since the uprisings of 2020 and is perhaps the largest mass arrest in Tempe, at least in contemporary memory. It also seems likely that there hasn’t been a comparable situation on the ASU campus since the occupation movement of the 1960s. It’s notable that regardless of strategic shortcomings and the ultimate loss of the encampment late on Friday night, our enemies evidently still perceived the occupation as enough of a threat to warrant its violent dispersal. We should ask ourselves, then: What is it about this moment that threatens them so sharply, that makes them afraid, and how might we turn that threat into a promise? The moment is not over and has not passed us yet. The space might be lost for the moment, but our dispersal comes with the gift of experience and the opportunity to re-emerge again.