Filed under: Action, Critique, Development, Editorials, Environment, Midwest

A few weeks ago, I met up with about 150 people in Keokuk, Iowa, to stop Dakota Access Pipeline construction in the small town and under the Mississippi River. By the end of the day, we’d stopped construction for about an hour, and 44 of us had been arrested, cited for trespass, released, and given dates to appear in court for an arraignment.

I had been in Iowa to attend an annual Catholic Worker gathering, a weekend of camping, roundtables, skits, and socializing, mostly with Christian anarchist folks from the Midwest who are engaged in hospitality, simple living with people at the margins, and social activism, either on farming communes or communal houses in cities.

Eight of us decided to take advantage of our proximity to construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline and spent Saturday, September 17, with protesters at Mississippi Stand, where Catholic Workers and others had already been disrupting pipeline construction for several weeks.

As we were driving toward the site on Saturday morning, we noticed a sign for “protest parking” at the end of a gravel driveway. We turned down the drive and met a kind family who was offering their yard and driveway as a parking lot for people coming to the demonstration. We parked and took a tractor-pulled ride down to the protest site.

Tractor ride from a parking area down to the protest site

As we neared the site, we passed a row of tents along the road where protesters had been staying since late August. In addition to the 24/7 protest at the camp, several actions had been carried out so far, including the construction of a barricade across an access road leading to the pipeline and attempts to enter the construction site. Several people riding in the trailer had participated in a protest during the previous week that included marching and chanting and were excited to be going one step further this week by attempting to physically stop construction despite possibly risking arrest.

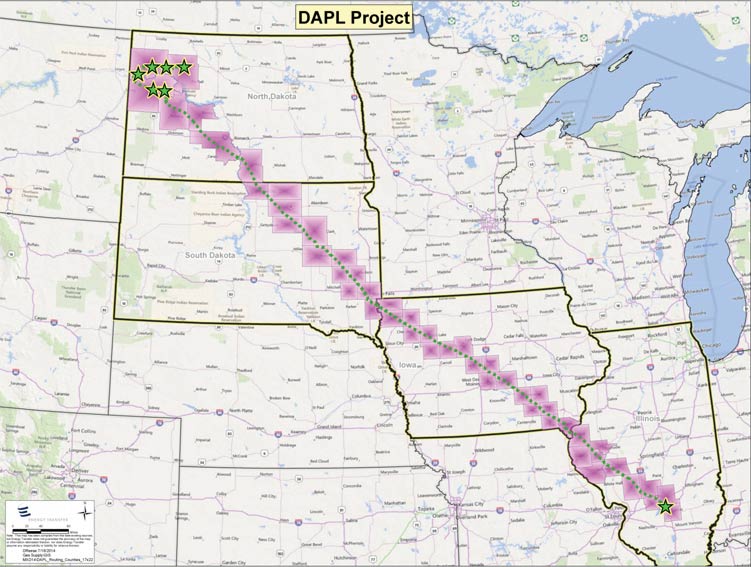

One person on the trailer spoke with sadness and frustration about her grandmother’s farm, which is one of the many residential properties that has been seized for the pipeline’s path. Nearly 350 miles of the planned pipeline stretches diagonally across Iowa before crossing under the Mississippi River in Keokuk and into central Illinois. Construction of Bakken’s Dakota Access Pipeline is known to have adverse effects on soil health, including compaction, changes in soil biology and fertility, and disruption of soil horizons, which affects drainage and root growth. Entire ecosystems depend on soil health, as it in turn affects vegetation and microorganisms as well as the animals and others that use vegetation for food and shelter. A leak in the Bakken pipeline could release oil at a rate of nearly one million gallons per hour and cause lasting effects–plant and animal death, soil and water pollution, and oil seepage of 30-feet deep in affected areas–as is the case in North Dakota, where Bakken spilled 840,000 gallons of oil in 2013.

Bakken’s planned pipeline route (with much construction already underway)

When we arrived at the gathering spot for the protest, a gravel parking lot along the Mississippi River, people were introducing themselves and sharing what had brought them to the protest that day. Many people were coming from Keokuk and other cities throughout Iowa and across the river in Illinois, and others traveled farther from St. Louis; Springfield, IL; South Bend, IN; Evansville, IN, and other places in the region. One person said the pipeline “doesn’t represent the world I want to live in,” and another said, “the earth’s health should come before corporate interests.” Many came in solidarity with those at Standing Rock or for their own kids, grandkids and future generations. I had come for many of those reasons, too. I also wanted to meet folks who are currently and directly affected by pipeline construction and to participate in resisting the pipeline’s (destructive) construction.

The morning’s pre-protest program included a talk on civil disobedience and principles of nonviolence, role playing to practice nonviolent responses to possible scenarios, and a centering prayer and song led by a Cherokee woman. There was also an explanation of the proposed action and time for folks to discern if they were willing to risk arrest, as well as a presentation about possible legal consequences.

In one of the role plays, everyone partnered up and took turns acting like a police officer and someone who was being arrested. I thought someone summed up the exercise nicely, saying that playing the role of a police officer “felt powerful,” while playing the role of someone being arrested “felt like being a human.”

One person gave a short presentation about the use of civil disobedience as a tactic, or perhaps even an obligatory step, toward fighting oppression and injustice. Intentionally breaking an unjust law and being arrested for it, such as during sit-ins during the civil rights movement, was described almost as a noble deed.

I had decided that I was willing to risk arrest. I wanted to experience planning and executing a nonviolent direct action with possible risk of arrest, something I hadn’t done before.

The plan we developed was for two groups of people to approach the construction site from different areas–one group would walk up an access road (property of Bakken) and another group through the woods (private property where owners had given permission to use the property for that purpose). According to organizers who had been in conflict with the construction for couple of weeks, it was likely that the group using the access road would be stopped by law enforcement fairly quickly, at which point people had at least two choices. They could stop walking toward the construction site and therefore likely avoid any risk of arrest but be unable to interfere with construction. Alternatively, people could continue moving toward the construction site, which would allow them to potentially stop construction, but would likely put them at risk of arrest for trespass, disorderly conduct, or interference with official acts. The group that approached through the woods faced a similar scenario, except that they would likely be at very low risk for arrest until they reached the end of the private property, which was within easy earshot and eyesight of the construction site.

People gathering to walk toward the construction site, with the Mississippi River in the background

Two of the other people I had come with had decided that they were willing to risk arrest as well. The three of us decided to stick together and take the route up the access road, as one of us wasn’t prepared to hike through the dense woods the other group would take.

I was already partway up the access road, talking with those I’d come with, when the remainder of the protesters at the base of the hill started moving up it, chanting phrases such as “water is life” as they walked. A group of police formed a line between the two groups of protesters, and when the lagging group reached the police, the group stopped moving and grew quiet. A police officer pulled out a piece of paper that he read in a loud but shaky voice, explaining that we were not allowed on the property and would be trespassing if we continued past the police line.

Many thoughts went through my head then and now as I’m thinking back on it.

Why did everyone stop moving forward? Why did everyone become silent (other than a few isolated shouts) for the police officer to read the statement? I felt disappointed that we were making their job easier.

I was questioning what it meant that I was already past the invisible line that the officer said we couldn’t cross. Was I already in an arrestable position? Was he technically saying I couldn’t cross back over the line? I felt confused and agitated, wondering if these minute details even mattered, since police make arrests–or don’t–based on whatever they feel like doing.

I’ve thought about the irony of the police, who supposedly “protect and serve,” stopping protesters, many of whom are trying to do just that. Why do the police protect and serve the big oil company, “their” forcibly-acquired land, their projects? If the police get their power to do so from authority–from the whole system built up around crime, punishment, lawyers, judges, politicians, democracy–how do we dismantle that? What power do we have as people, and how do we tap into that?

As the police officer finished reading the statement, I started walking farther up the hill. The others who were already past the police line also continued on, and many from the larger group joined us.

Protesters approaching the first line of police en route to the Bakken pipeline construction site on the other side of the hill

We met a second line of police. Some people were singled out and stopped, and others of us continued on and encountered a third line of police. Here, one of them called out, “This is where it stops!”

The police officer directly in front of me looked nervous and kept looking over at the other officers as if begging someone to step in and take over. The officer spoke in an unsteady voice and choppy sentences. All around me, police officers were approaching people, having short conversations with them, arresting them and lining them up once they’d been handcuffed (zip-tied). It was like the person in front of me missed the training and didn’t know what to do or wasn’t prepared to do it.

I wasn’t quite sure what to do either. In our role plays, the police officer was always aggressive and authoritative, but the person in front of me was scared and hesitant. I decided to try to step around.

The officer said, “No,” and I stopped.

Again, looking back, I think I could have pressed on. But maybe I didn’t know what to do just as much as the police officer didn’t know what to do. So we fell into familiar roles–with the police officer saying what to do and me doing it. I was nervous, too, because when it comes down to it, police can always just resort to their tasers, their guns, and the system that supports their harassment and control.

I asked, “Am I under arrest?”

The police officer looked around at what the other police officers were doing, then back at me, but didn’t respond.

I knew from the pre-protest legal talk that under Iowa law, to be guilty of trespass, one has to enter a space without permission, be explicitly asked to leave, and continue to stay in the space. I said, “If I’m not under arrest, I’m going to keep walking,” and I took a few more steps.

The police officer said something like, “you’re trespassing.”

Knowing that Iowa code also defines trespass as “unjustifiably” being in a space, I challenged the assertion, saying that I thought I had a justified reason to be there, to stop the destruction that was taking place.

This kind of back and forth went on for a while, until one of the other police officers was free, came over, and said I could leave or get arrested. I said more of the same and that I’d stay, and I was arrested.

The group at the base of the access road parted to make way for those who were arrested to come back down the hill

Since I was last to be arrested, I was first to go back down the hill, through the crowd of protesters and into the paddy wagon.

And that was exhilarating. In such a weird way.

In that moment, I was in a new place surrounded by various people, only a few of whom I knew. I was doing this thing I’d never done before–getting arrested–and doing it in this strange, controlled, predictable way. I was listening to someone I’d met, who was singing–belting out–a song in his native language as we all walked back down the hill. I was taking in the sights and sounds and energy of fifty or more people cheering as we walked through the parted crowd. I was noticing the Mississippi River, majestic as ever, in the background. I couldn’t help but grin.

But yet, what had we accomplished?

Someone (in blue) sings while walking down the hill after being arrested

One arrested person (in blue) celebrates the arrest triumphantly, while another (center, in stripes) cries

We piled into police vehicles as directed and were transported to the county jail, where we were each photographed, issued a ticket for trespass, assigned a date to appear in court, and released.

As others who were arrested trickled into the jail, I learned about the efforts of the group that went through the woods toward the construction site.

Protesters emerging from the woods and continuing toward the construction site on the horizon

As predicted, protesters who went through the woods were able to get rather close to the site before police presented them with the option of stopping or getting arrested.

Because the protesters were close to the construction workers, the workers reportedly stopped what they were doing–turned off the huge machine that was drilling through the ground–and turned their attention to watching and snapping photos of the protest. For an hour. I was told that, eventually, energy for chanting and carrying on dwindled, and the protesters retreated.

Drilling deep into the ground leading to the Mississippi River at a halt while construction workers (left) watch protesters

I’m left with bittersweet feelings–the satisfaction of construction having stopped for that one hour as well as confusion, disappointment, thoughts, and unanswered questions about my experience and the effectiveness of our tactics.

Was getting arrested really “worth it?” Getting arrested, in itself, didn’t physically stop construction.

Did it draw attention to the issue? Maybe. But did it matter that I was arrested–is 44 people getting arrested better than 43? Would it make a difference if only 20 people were arrested? Or even just a few? I don’t know.

If I were to plead not guilty and take the case to trial, would that draw attention to it? Would I get a ruling in my favor that paves a way for others to carry out actions like this one without getting arrested? Not likely.

So then, are we just fattening the wallet of the state with the fines we’ll get? Are we just a training program for the police so they’re better prepared to handle the next protest?

I also think about how the action relates to privilege. Many (but definitely not all) of the organizers and people who risked arrest were white and had the ability to pay fines, which was seen as the likeliest consequence of the action. The action likely excluded some people of color or asked them to take a greater risk. It likely excluded people who knew they wouldn’t be able to pay a fine as well. What kind of action did these people want to do? At the same time, the action brought in many locals who were participating in their first protest or first act of civil disobedience with a risk of arrest, and I wonder what value that adds to the action and the overall momentum and effectiveness of the NoDAPL compaign.

If the goal that day was simply to stop construction for as long as possible, I wonder what would have been more effective. For instance, if we all would have gone through the woods to the edge of private property, where we could legally be, and put all of our effort into distracting the construction workers, maybe we could have found creative ways to keep ourselves engaged and could have stopped construction for longer than an hour.

I wonder, too, what people are taking away from the action. I know I’ve learned things about myself. I know I’ll have more confidence next time around, more creativity, more ease. I have a shared experience with these friends and strangers. I have a story to tell. Again, is that worth it?

On the flip-side, am I really losing anything by getting arrested? Probably not. A few hours of my time here and there. A reason to go back to Iowa (for court) or to avoid Iowa forever (or at least avoid getting pulled over there). Will I have to check a box on some future job application saying I’ve been arrested? Maybe. But fuck jobs.

I’m also left with an approaching arraignment on October 19th in Iowa (a six-hour drive from Evansville) and details to figure out about that–to go or skip it? To plead guilty or not? To pay fines or let them carry over to a collection agency and go unpaid? The two folks I’d come with who were also arrested are planning to skip. One of them is already “a wanted man in two states” for his activism. He figures, why not add a third? The other person opted to plead guilty by mail.

I plan to go to my scheduled arraignment. I see that I’m only able to participate in this direct action at all and can only consider skipping the arraignment because of privileges I have in being white, being adept enough at navigating the legal system and middle-class institutions, and having other privileges I’m less aware of. I don’t like that that’s the case. I think that when it’s all over though, I’ll be glad to have gone through the whole sentencing process; maybe next time I get arrested it won’t be such a simple, planned procedure; maybe it will be nice to have gone through it before. But again, I’m sitting in a strange place of privilege to be able to take that perspective. I’m not sure what to do with that.

I’m also looking forward to spending time at the Mississippi Stand camp, which from what I’ve heard, is developing into an interesting temporary transient community with daily direct actions as well as shared meals, space, responsibilities and resources, which is totally my jam.

I don’t plan to pay the fines. They can take away Iowa state tax return money and suspend Iowa driver’s licenses, but as far as I can tell, I should be able to get away with not paying them. I don’t want to support the things the money would be used for. I’d rather take jail time than actually pay a fine (there’s a 30-day maximum for trespass), but I’m hoping that doesn’t come up.

I’m hoping, also, that as I make my way back to Iowa next week, I’ll be filled with more stories to tell and questions to ask myself. Check back for “Anti-Dakota Access Pipeline in Iowa, Part 2” in a few weeks!