Filed under: Anarchist Movement, Bloc Party, Canada, Featured, Incarceration, Interviews, Political Prisoners, Repression, The State

Last week we shared an overview of the history of Canadian prisons and the resistance to them. We’re excited to share an interview with the authors of that history–two friends from Quebec and Ontario, who are deeply engaged in the struggle against prisons. We took the opportunity in speaking with them to dig a little deeper on a few of the topics they touched on last week as well as discuss similarities and differences between the U.S. and Canadian prison industrial complex.

In this interview the authors speak about one way those of us in the States can support prison/er organizing across borders, which is essentially decentering the U.S. in the conversation. In an effort to do just that, we’re publishing a downloadable zine version of both parts of Our Neighbors to the North. We hope you’ll add it to your zine tables and distros, sharing it with your comrades both inside and out.

Our Neighbors to the North PDF Here

Bloc Party: You talked about the high rates of suicide in women’s facilities in Canada and mentioned the story of one woman named Ashley Smith who ended her life while in custody in 2007. Can you tell us more about the struggles of women incarcerated in Canada?

Some Friends from so-called Canada: There’s a lot to say about the struggles of women incarcerated in Canada, so take this as a snapshot.

First, we want to highlight some individuals who have been speaking out about how the prison system effects women in Canada. Sheri Pranteau, a Cree woman from Winnipeg, Manitoba, who is on parole with a life sentence, has spoken publicly about the issues facing indigenous women in Canadian prisons (for instance at this event, among many others and on this CBC documentary). Arlene Gallone, a Black woman who lives in Montreal, is in the process of suing the Correctional Services of Canada in a class action lawsuit for putting her in solitary confinement for long stretches of time in the federal prison for women in Joliette, Quebec. You can hear her and her lawyer talking about the case here. Lastly, we want to highlight Nyki Kish, a wrongfully convicted activist currently serving a life sentence at the Grand Valley Institute for Women in Ontario. She has a blog where she writes about her experience in prison and her analysis of the prison system and you can hear audio from her here and her website is also at freenyki.org. She is still in prison. All of these individuals talk about conditions facing women in prison in so-called Canada, so go check them out in their own words!

Second, we want to highlight issues being brought to light in general in terms of struggles facing women in prison. The first is the situation facing pregnant women and newborn babies in the prison system. Most women who give birth while incarcerated have their babies taken away from them right away. Folks on the inside and the outside have been advocating for, firstly, an end to incarceration, period. As part of that advocacy, there was an effort to develop guidelines for Mother-Baby Units in the prison system so that newborn babies could stay with their mothers. As of 2016, some prisons in BC are implementing programs for some mothers. But, many other women face long bouts away from their kids while incarcerated, including newborns whose fates are decided by social workers unfamiliar with the programs that are available. Most of the news around this in the past few years has been about provincial prisons in British Colombia. The federal government responded to the news by increasing the amount of existing spots in the mother-baby programs in federal institutions, although spots remain limited.

Last, we want to highlight issues facing trans women incarcerated in Canada. Up until very recently, trans women were incarcerated in prisons for men in Canada, a reality that exposed many women to violence and harassment. Due to a lawsuit brought on the inside by Fallon Aubee, and advocacy on the outside, like the time when Teresa Windsor asked Prime Minister Trudeau why trans women were being incarcerated in men’s facilities at a town hall in Kingston, Ontario, the Correctional Services of Canada have released a new policy regarding trans women in prison in the last month. As of January 2018, Correctional Services Canada will let incarcerated trans people choose whether they want to be incarcerated in a men’s prison or a women’s prison and that choice can be based on gender identity, although we’re guessing that this change will be far from accessible for all who want it because of the language that is still in the policy regarding “safety concerns” and the continued reality of transphobia both in prison and outside prison.

Given all this, it might sound like we think shit is pretty good for women in prison in Canada. Not the case! Though the government has changed some things in the last five years, many of the issues we have seen playing out in men’s prisons (terrible food, lack of access to programming, lack of access to educational opportunities, overcrowding, lack of access to outside community, restrictive conditions for visitors, and on and on and on) also plague women’s prisons, sometimes in a magnified way. For instance, the lack of access to adequate programming has consistently been much more of a problem in women’s prisons than in men’s prisons. There are also fewer women’s prisons in Canada, making it more likely that women will be incarcerated far from their families and thus, receive fewer visitors. The smaller numbers of women in prison in Canada means that people placed in maximum security units are essentially in solitary confinement.

In the latest report from the Office of the Correctional Investigator there is a section on the maximum security units in federal prisons for women. The report details how cramped and closed the cells are and how being forced into the maximum security wings means that one can no longer access programs, education, or the gym or library. It says, “[prisoners] can be subject to strip searches every time they return to their unit. This system is unique to women’s corrections”. In short, without even getting into high rates of suicide and the story of Ashley Smith (which is heartbreaking and you can read about the inquest into her death here and know that we are not aware of any of the recommendations being implemented), its not hard to see that struggles facing women incarcerated in Canada are intimately connected to systems of hetero-patriarchy, settler colonialism, white supremacy, ableism, and anti-Blackness.

Bloc Party: Also, in the U.S. women are the fastest growing prison population. Do you see this trend in Canada as well?

Some Friends from so-called Canada: As of 2015/2016, 16% of adults admitted to provincial prisons were women. For federal prisons, women are between 7 and 8% of the prison population. The total number of women in prison in Canada (in both provincial and federal prisons) has been increasing in the past 20 years. In 1999, women represented 10% of the population in provincial prisons and 5% of the population in federal prisons. The number of indigenous women in prison increased by 109% between 2001 and 2011. 41% of women in provincial prisons in 2013 were indigenous (fuck Vice News but this article is pretty good). As of 2017, Indigenous women represented 50% of the maximum security population in federal prisons for women. Like we said in our longer article, the history of settler colonialism in this country really clearly shapes who ends up in prison.

Bloc Party: Resistance in women’s prisons in the States can be hard to track, almost to the point where people have the idea that it simply doesn’t happen. In our experiences of connecting with rebellious women on the inside, we’ve heard that resistance often manifests differently than you might see in a male facility. Do you see this hold true in Canada as well? What can you tell us about resistance among incarcerated women currently?

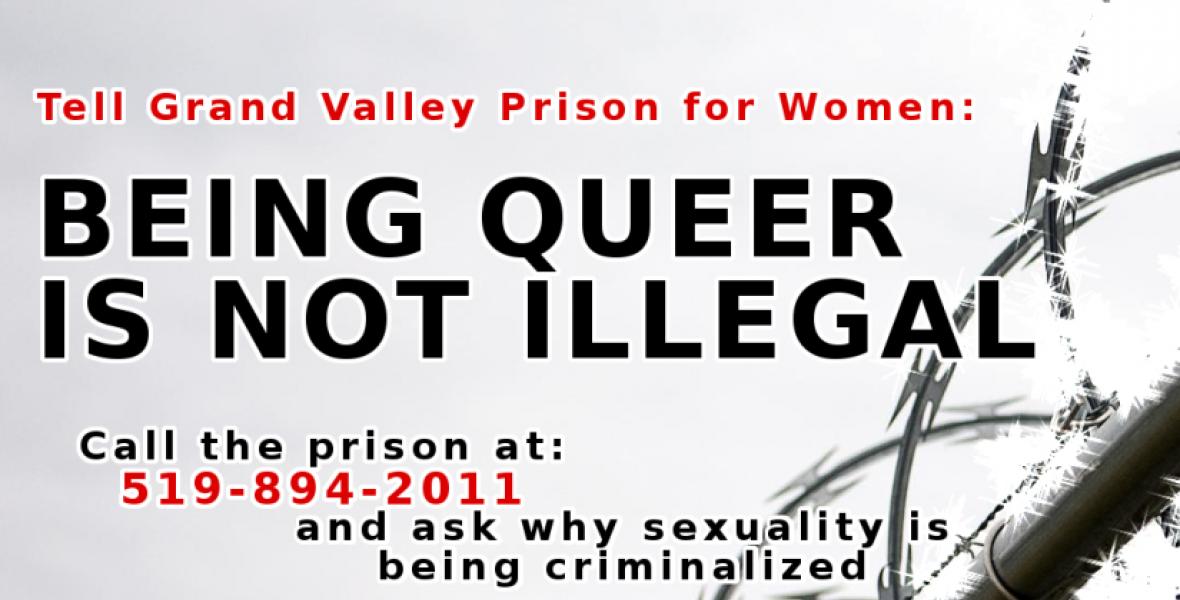

Some Friends from so-called Canada: In 2015, women at Grand Valley Institution were facing repression for being in queer relationships (having a romantic relationship with a fellow prisoner is against CSC policy). Folks were in the hole, facing institutional charges and transfers to different security ranges. They decided to get organized. The subsequent campaign, called GVI Watch, was supported by people on the outside, who organized a call-in campaign to the prison’s administration. In the end, queers in GVI were allowed to create a queer support group, although individuals were still fighting their institutional charges and changes in security classification.

(This campaign is not ongoing and ended in 2015)

In November 2015, women in the now-closed provincial prison in Montreal, called Tanguay, released a statement about austerity measures in prison. Decrying the slashing of public services in Quebec, the statement describes the small food portions, the moldy conditions, and the dilution of cleaning products available to prisoners. It also explains the lack of access to medical services, the lack of prenatal care for pregnant women, and the impact of harsher sentencing. The letter demanded “food that meets our nutritional needs, accessible and adequate medical services, specific follow-up for pregnant women, care for people going through withdrawal, adequate provision of sanitary products, more social programs, more classes that can lead to a job, access to therapy” and calls for a social strike. The Tanguay Prison for Women was closed in the year following the release of this letter and all the women were moved to an ex-federal prison in Laval, a suburb off the island of Montreal.

Bloc Party: You talked about the overlap and divergences of abolitionists and anarchists. You said a few things that we took immediate note of and hoped you might expand upon. You said that abolitionists tend to be “more supportive of and comfortable with ‘non-violent’ resistance.” Do you find that they restrict support efforts of those prisoners willing to engage in other tactics? If so, what has that looked like and how have anarchists responded or intervened?

Some Friends from so-called Canada: We spent a lot of time discussing this question, both between us (the authors) and in consultation with comrades. It has become clear to us that people use the term ‘abolitionist’ in different ways. There are anarchists who also identify as abolitionists and there are abolitionists who become Senators and everything in between. However, we have not seen any evidence that abolitionists (as a broad category) restrict support efforts of prisoners who engage in tactics other than ‘non-violence.’ Instead, we think that just like on the outside, there is a class of people in prison who are relatively articulate and may self-identify as activists (and some of them as abolitionists). Some of these prisoners, in trying to be ‘constructive,’ will channel the frustration and anger of others towards calls for political reform, legal battles and non-violent resistance. Many abolitionists, especially those with academic credentials and institutional connections (ICOPA), are well-positioned to advance these struggles by advocacy in mainstream media, activist campaigns, lobbying government, etc. So those are the voices that get heard in the end.

To be clear, we think many abolitionists are solid, committed people and we’re glad they do this good work. Non-violent resistance is often the best practical option available to prisoners who suffer severe consequences for the slightest insubordination. Still, abolitionists and anarchists both tend to lack connections among the non-activist prisoners. Some anarchists are looking to break out of this specific milieu. One way to do that is to reach out to prisoners facing repression for their participation in uprisings, such as the Saskatchewan Penitentiary Riot.

Bloc Party: You also mentioned an abolitionist organizer, Kim Pate, who now sits in the upper house of parliament. You wrote, “this raises the question of whether prison abolitionism as an ideology implies meaningful opposition to the state itself.” We’ve discussed this before in Bloc Party – what does it mean when our struggles against prison from an anti-capitalist and anti-authoritarian perspective are taken into the mainstream? What do we need to be wary of? We’re certainly not at the point of having self-identified abolitionists in the Senate here in the States, but in 2016 even Hillary Clinton was speaking out against “mass incarceration.” What do you think anarchists need to be wary of in collaborating in anti-prison efforts with those who don’t hold the same political values?

Some Friends from so-called Canada: In Canada, the Senate is appointed by government, not elected. Kim Pate claims that she accepted the position because in doing so, she couldn’t be banned from entering any prison in the country. Yet, she has stopped openly talking about abolition since being appointed, and that is troubling. Just like when prison justice activists talk to the mainstream media and leave open the possibility of prison for “the worst of the worst,” it becomes clear that being against mass incarceration is different than being for the abolition of prison.

We think it’s important to be able to collaborate with others across political difference while maintaining our integrity and refusing to water down our politics. When we approach it this way, we can actually hold others accountable for the politics they profess and keep openly pushing an anarchist, anti-prison politic that is true to what we want. That said, there is a point at which a person’s choices mean that they shouldn’t be trusted, and another point at which we begin to recognize them as enemies. We don’t necessarily consider Kim Pate to be an enemy, but her appointment to the Senate should be a wake-up call for those of us who oppose the state about the degree to which some self-described abolitionists are willing to collaborate with government. Why was Pate’s transition to the Senate so unsurprising, seamless and even uncontroversial?

Kim Pate’s decision to accept the Senate appointment also raised questions for us about social position. In reality we are socially closer to Kim Pate than we are to many many people in prison. She is really two or three degrees from us socially. That has happened for a few reasons, one of which is about social position – she’s a white, university educated, upper-middle class woman who is working as a professional. There is a lot of overlap there, not just with us, but many people in our milieu. We think being aware of patterns in the demographics of the people who are around us is a smart thing to do as anarchists and is connected to organizing with people who don’t hold the same political values as us. As anarchists, we need to think more about who we are reaching out to, who we are building coalition with, and who we are building close relationships with as those are all political questions that can affect our ability to meet our goals. In the end, getting clear on our collective intentions and goals in any given struggle can help a lot in terms of bridging differences in values and social positions.

Bloc Party: There are stark differences in the histories of Canadian and U.S. prisons as well as striking similarities. The 1970s were a time of widespread, global civil unrest. From prisons to the streets, the world was in revolt against institutionalized power structures of all stripes. Here we are again, in a moment of widespread civil unrest that spans the globe. From the prison strike of September 2016 to struggles for Indigenous sovereignty across the Americas, we’re seeing tremendous upticks in struggle. In what ways do you see prisoners resisting in Canada? Do you think word of the prisoner resistance here in the States has reached inside the barbwire there and had any impact on organizing efforts or resistance?

Some Friends from so-called Canada: We want to preface this answer by saying it’s very hard to speak of Canada as a coherent thing. Canada is a very large country with strong regional identities, which is why we are mostly limiting our points to the provinces where we live, Ontario and Quebec. That said, it does make sense to speak of a national context in terms of prisoners incarcerated in federal institutions, as the federal government controls the laws and politics that largely determine the conditions of confinement. So it makes sense that federal prisoners, who get transferred all over the country (definitely if they take a leading role in any resistance inside) have some sense of a shared history and connection, and as a result we see traditions like Prisoners Justice Day across the country, and sometimes a strike started in one province will spread rapidly to the others.

Prior to 2015, Canada endured 10 years of Conservative Party rule, which was heavily focused on a ‘law and order’ agenda. Prisoners bore the brunt of countless attacks on their dignity, conditions and quality of life, including both significant changes such as the introduction of mandatory minimum sentencing, and petty affronts such as the elimination of pizza party fund raisers for charity. Predictably, these almost daily attacks on their lives, combined with a total unwillingness to even appear interested in compromise, sparked a lot of resistance, although it also lead to a situation of depression and resignation for some.

In 2015, Liberal Party Leader Justin Trudeau was elected Prime Minister. He is young, charismatic, well-versed in anti-oppression jargon, and uses a lot of Obama-like rhetoric: hope, change, and sunny ways. Shortly after being elected, Trudeau published an open ‘mandate letter’ to his Minister of Justice, including a section on prison reform:

You should conduct a review of the changes in our criminal justice system and sentencing reforms over the past decade … Outcomes of this process should include increased use of restorative justice processes and other initiatives to reduce the rate of incarceration amongst Indigenous Canadians, and implementation of recommendations from the inquest into the death of Ashley Smith regarding the restriction of the use of solitary confinement and the treatment of those with mental illness.

In Ontario, we’ve seen a significant shift where much of the left has re-oriented its strategy in the hope that the new government will be persuaded to enact various reforms. Inside, we still see a lot of unrest, but not ‘tremendous upticks,’ as some folks are definitely still holding out for a ‘political solution’ to certain grievances . We’re wary of this renewed sense of hope in government, and the degree to which it can pacify our struggles. That said, it’s too early to predict the level of resistance to the current regime, as unmet expectations can also have a radicalizing effect.

It does seem that prisoners here are aware of what’s going on south of the border, and this has been true for a long time. While they were very different in many ways, the Kingston Pen Uprising occurred only a few hours drive away and a few months before the Attica Uprising in 1971. While it can be difficult to pass news through the walls, anarchists and other folks here have put some effort into spreading word of unrest down south such as the September 9th national strike in 2016, which in one instance led to a support letter from inside.

Bloc Party: We loved the name of the ’90s prisoner newsletter you mentioned briefly in your article: Bulldozer: The Only Vehicle For Prison Reform. Fucking classic! Prison newsletters have a vibrant history in the U.S. as well. In the last 5 years we’ve seen a number of prison newsletters published by anarchists in collaboration with contacts inside prisons. After many years of anarchists primarily focusing on traditional ideas of political prisoner support (as a response to the large number of political prisoners taken in during the 1960s and ’70s), there is a recent tendency towards focusing on broader prisoner support amongst anarchists. From your history and overview, it seems like anarchists in Canada have generally taken a broader approach to prison rebellion and prisoner support for much longer. Can you speak to this and share any thoughts?

Some Friends from so-called Canada: Prison sentences do tend to be shorter here than in the U.S. and we have not seen many long-term ‘political’ prisoners/prisoners of war incarcerated in this country in recent decades. One notable exception would be the Direct Action 5, anarchist urban guerillas active across Canada in the 1980s, who were given long prison sentences in 1983. So anarchists organizing prisoner support here have mostly put their efforts into contributing additional energy to U.S.-based political prisoner support and/or working with politicized prisoners active inside, overlapping with the prison justice & prison abolitionist movements. Jim Campbell, one of the founding members of Bulldozer, actually wrote an interesting report-back from the 1994 Anarchist Black Cross Conference in New York, which we would encourage readers to check out for more perspective on this question.

Bloc Party: Can you talk a little more about the importance of the pre-existing infrastructure of Anarchist Black Cross chapters in the response to repression around the G-20? How did that play into anti-repression efforts?

Some Friends from so-called Canada: We asked this question to a friend involved with ABC Toronto in 2010, who emphasized the importance of pre-existing relationships that made it possible to draw on a large network of ABC chapters and related groups for fundraising, legal support and to spread the word very quickly. There were websites, publications, newsletters and listservs in place with large audiences who could be mobilized to support arrestees. Finally, having a regular presence in Toronto meant that people who wanted to get involved with support work had a clear entry point. In Montreal, there was no ABC at that time. A lot of the support was coordinated by folks involved in the CLAC, some of whom had experience from the Quebec City FTAA Protests in 2001.

Definitely being involved in ongoing projects to support prisoners can help anarchists figure out how to support each other when shit hits the fan. Knowing the ins and outs of the prison system before you or your best friends get arrested can give you a sense of what could be coming and how to navigate the struggles ahead.

Bloc Party: In what ways do you think we can better support our comrades in Canada in their efforts to bulldoze these prisons? What does prison abolition collaboration look like across borders?

Some Friends from so-called Canada: De-normalize and de-center the US in how we understand ‘what’s going on.’

Sometimes when doing prisoner support, we can get caught up in the specificities of the particular prison (or state system) that we’re facing. When thinking about collaboration across borders, it’s important to also see the similarities across jurisdictions in order to transform individual experiences into collective struggles.

For instance, the Demand Prisons Change letter that some prisoners in Canada wrote shares many similarities with the list of demands issued from Attica during the 1971 uprising. Struggles about conditions in prisons are often about basics of life like food, communication with other humans, opportunities for learning and growing, and access to family and community. When we understand each other better, effective solidarity across borders becomes more possible, and we hope this article is a contribution in that direction.

In moments where we need support the most, what we actually need is usually pretty clear, but our capacity can be lacking. When things are quieter, we can build capacity by establishing material infrastructure for sharing resources and skills, making personal connections of affinity and solidarity, as well as setting up channels for private and public communication across borders.

Bloc Party: “At least you’re not in prison in the US.” We’ve discussed with comrades here in the States how a primary export of the U.S. is the prison industrial complex. We saw that reflected in your historical overview. In both the expansion period and “Marionization” of the 70s, as well currently with the harshening of conditions. In seeing a presentation by you that covered the history and current context of Canadian prisons, we were struck by how much more access to things prisoners have there that just seem wild by comparison. But, the U.S. seems to be ever expanding its horrifying bullshit across the border. Do you see that reflected up there, and if so, in what ways?

Some Friends from so-called Canada: It’s true that certain privileges and policies exist here that seem unthinkable in the U.S. Some of these measures were won through struggle, others were the state’s attempt to contain the general unrest in the 1970s, while some others are initiated by government because they more effectively fit into a ‘rehabilitative’ ‘correctional’ framework. As we noted in our history piece, usually when the government offers prisoners a carrot, there is a corresponding stick, and the spectrum of social control that divides and classifies prisoners is expanded.

In some ways, things up here are just different, not better. We don’t want to downplay the brutality of the U.S. prison system, nor do we want to fall into the trap of Canadian exceptionalism or the false dichotomy of “punishment vs. rehabilitation,” which are two tactics in the service of social control. On average, (although there is no “life without the possibility of parole” up here) prisoners with a life sentence serve more of that time in prison than prisoners with a life sentence in the US. It’s also true that for a long time, the Canadian federal system has liked to claim that it is more effective at ‘correcting’ people than the Americans, which translates to a more elaborate regime of routine, discipline and surveillance, all guided by a very detailed ‘correctional plan’ tailored to each individual prisoner by a team of cops and social workers and screws. This is why in Canada, you can’t send a book directly to a prisoner (it must go to the librarian), or you have to be pre-approved by the administration before being allowed phone calls or visitation with a prisoner.

If we understand the Canadian state as liberal order, where incarceration can sometimes be a little more comfortable than south of the border, then our task as anarchists in this place is to develop analysis and practice to effectively attack liberalism.

We just emerged from a decade of Conservative federal rule heavily influenced by the U.S. right. In times of rollbacks and crisis we might find common cause with liberals, and we try to avoid fighting simply to return to the shitty status quo and not for our dreams. We can’t forget that the Liberal Party is Canada’s “natural governing party” and in many ways our primary enemy as anarchists.

Bloc Party: Thank you so much for writing this piece to share with IGD readers. We’re excited to share it here on the site as well as in zine format to spread more widely!

Bloc Party will be back next Friday with prison and prisoner-related updates as well as news about repression. Until then!