Filed under: Announcement, Event, Southeast

Atlanta Community Press Collective reports on a call for mass action against the Cop City project on November 13th.

By: Matt Scott

Update: Block Cop City organizers now say the nationwide tour will cover 70 cities.

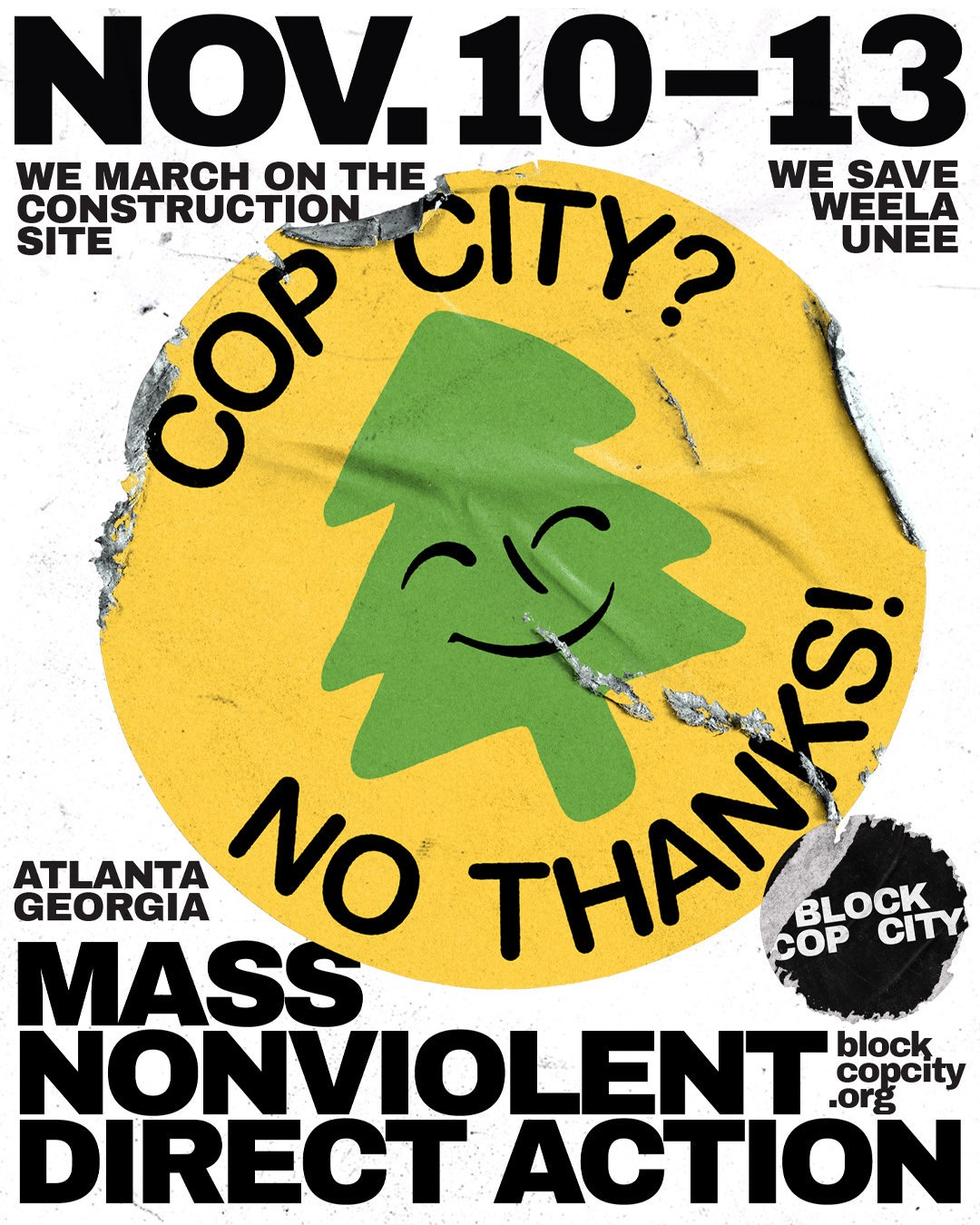

Just days after members of the clergy and other people of faith chained themselves to construction equipment at the proposed Atlanta Public Safety Training Center site, a new group, Block Cop City, announced plans for a mass action on Nov. 13 to halt construction of the facility.

“It is useless to wait,” the landing page of the group’s website reads. “With our future on the line and the whole world watching, we’ll take a stand to bend the course of history. If the city government does not halt construction in order to listen to the people, then we will simply have to do it ourselves: a People’s Stop Work Order.”

The group says it plans to hold a 50-city tour in the runup to the mass action and then a convening in Atlanta beginning Nov. 10 and ending with the mass action at the construction site.

This is not the first mass action called by the multiyear protest movement known as the Stop Cop City Movement. The movement previously called for six separate “Week of Action” events over the last two years, in which national and sometimes international movement supporters joined locals and travelled to the South River Forest in unincorporated DeKalb County just outside of Atlanta for a week of rallies, concerts, teach-ins and food festivals.

And sometimes protests.

The fifth week of action, held in March of this year, came just a month after early construction work began at the training center site and saw the largest gathering of the six. The week began with the “Weelaunee Music Festival,” a two-day event invoking the native Mvskoke name for the South River that runs through the eponymously named forest. On the second day of the festival, a group of between 150-200 individuals departed the concert grounds and walked about a mile to the training center site where some of the crowd torched construction equipment and threw fireworks at a nearby police staging area set up to stop any protesters from entering the construction area.

Law enforcement officers from at least five different agencies responded an hour later by raiding the music festival and arresting dozens of concertgoers. Prosecutors charged 23 people with domestic terrorism, including an attorney for the Southern Poverty Law Center who was working as a National Lawyers Guild legal observer at the time.

The Stop Cop City Movement is comprised of sometimes loosely affiliated groups and organizations using a variety of tactics in the pursuit of stopping the facility for which the movement is named.

The newest group to the movement, Block Cop City, says November’s action will not engage in the tactic of property destruction and economic sabotage used in March and at other points over the last two years. The group plans instead to engage in a tactic known as “non-violent direct action,” a style of protest commonly affiliated with Civil Rights Movement leader Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. “This action will employ non-violent tactics,” the group’s FAQ page reads, “not because we accept the state’s false dichotomy of legitimate and illegitimate protest, but rather, because we believe that a commitment to non-violent tactics will best allow us to stick together and overcome the police’s attempt to isolate and divide us.”

Non-violent protest against Cop City is not without its risks. On Sept. 5, Georgia Attorney General Chris Carr recently unveiled Racketeering (RICO) indictments against 61 individuals allegedly associated with the Stop Cop City Movement. RICO convictions carry up to 20 years in prison in addition to penalties for the felonies alleged to underly the RICO charges. The attorney general’s office argued that acts done to prevent the construction of the facility fall under the alleged conspiracy. Some of the alleged acts listed as evidence in support of the indictment include one man signing his name “ACAB” – an abbreviation for “all cops are bastards” – and reimbursements for the purchase of glue or food.

Still, for individuals associated with the movement, there are few ways to attempt to halt the facility that do not involve risk. For years, those opposed to the facility tried to engage the traditional political system without much success. Cop City opponents called in dozens of hours of public comment to the Atlanta City Council over the course of Summer 2021. On the day it approved a ground lease to the Atlanta Police Foundation for the construction of the facility, the City Council heard over 17 hours of public comment with an estimated 70% asking council members to vote against the lease. That same day, the Atlanta Police Department arrested a group of individuals protesting Cop City outside then-City Council Member Natalyn Archibong’s house in East Atlanta.

This year, opponents engaged in dozens more hours of public comment against Cop City in June during the run up to a City Council vote to fund construction for the facility. On the day of the vote, some people waited over 15 hours for their chance to speak. Only a small fraction of those who spoke that day voiced their support of the facility. Still, despite the overwhelming opposition to the facility and the recent revelation that the taxpayer price tag of the facility was more than double what city officials first claimed, the City Council voted 11-4 in favor of providing $67 million to the Atlanta Police Foundation for the project.

More recently, the Cop City Vote Coalition launched a referendum campaign to add a ballot measure asking Atlanta voters to decide whether to overturn the ordinance authorizing the Atlanta Police Foundation’s lease of the training center site. This too was met with hostility from the city. In July, Mayor Andre Dickens told reporters that the referendum could not succeed “if it’s done honestly.” In legal filings, attorneys for the city have argued that Courts should strike the Georgia law enabling referendums rather than allow residents of neighboring DeKalb County collect signatures on the referendum petition. Then, in August, the city revealed plans to engage in a voter suppression tactic known as signature matching to validate, or invalidate, petition signatures.

On Monday, the Cop City Vote Coalition turned in over 116,000 signatures on the referendum petition to cancel the lease. As they prepared to drop off 16 boxes of signed petitions, City officials informed coalition organizers that the city would receive and store the petitions, but would not begin validating and counting signatures until a lawsuit currently in the Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit is resolved. The coalition contends that the city can at any point begin to validate the referendum petitions or unilaterally act to put the referendum question on the November ballot.

The 116,000 signatures the referendum coalition gathered represents over 20% of the Atlanta’s total population and is a larger number than the turnout of the last municipal election in 2021.

In August, Kamau Franklin, founder of Community Movement Builders and longtime opponent of Cop City, warned that city official’s failure to adhere to the will of the people would result in opponents taking alternative actions to stop the facility.

“If the City needs to see a demonstration of the people’s commitment to this issue, we’re happy to provide one,” said Franklin.

It is into the milieu that the Block Cop City group announced plans for the November mass action.

“On the morning of November 13,” the group states, “masses of people from across the city and country will gather in the Weelaunee Forest and bring construction to a halt. Together we can Block Cop City.”

photo: Felton Davis on Flickr (CC BY 2.0)