Filed under: Borderlands, Editorials, Immigration, Mexico, Repression, The State, US

It is difficult to summarize all of the things which have occurred the last few months. It is now monsoon and the rains have come to the desert to wash away some of the grit – to revive us and to breathe life back into this hot, sad summer. The rains feel blessed after record highs and stifling heat, but they are not enough. How can we find redemption or hope when there is nothing to discuss but death, and the price to pay for discussing it is also…death.

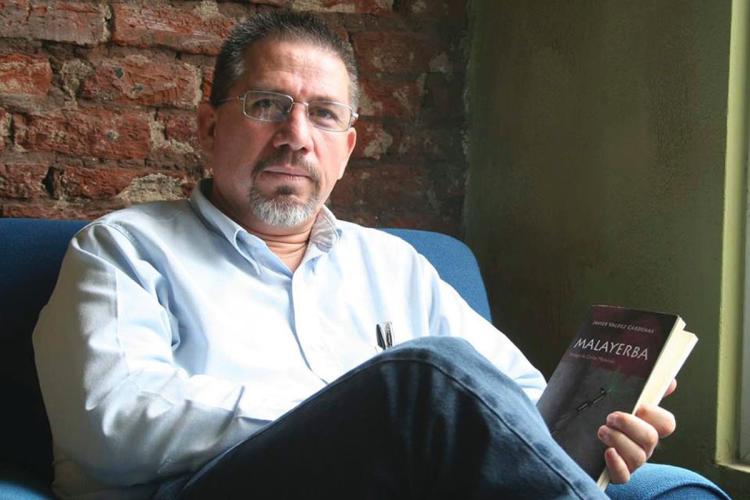

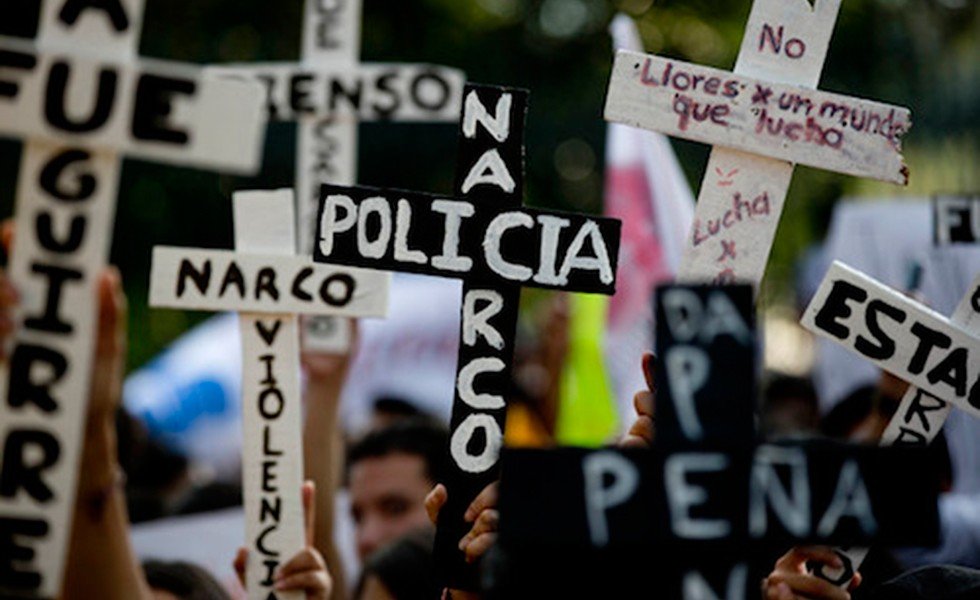

In May, Miriam Rodríguez Martínez, who successfully investigated the kidnapping and murder of her 14-year-old daughter Karen Alejandra by the Zetas cartel, was shot 12 times and killed in San Fernando, Tamaulipas. There has been an upsurge in violence since El Chapo’s extradition. Recent feature stories on the drug war are full of quotes from now-dead journalist Javier Valdez Cárdenas, who was also shot and killed in May.

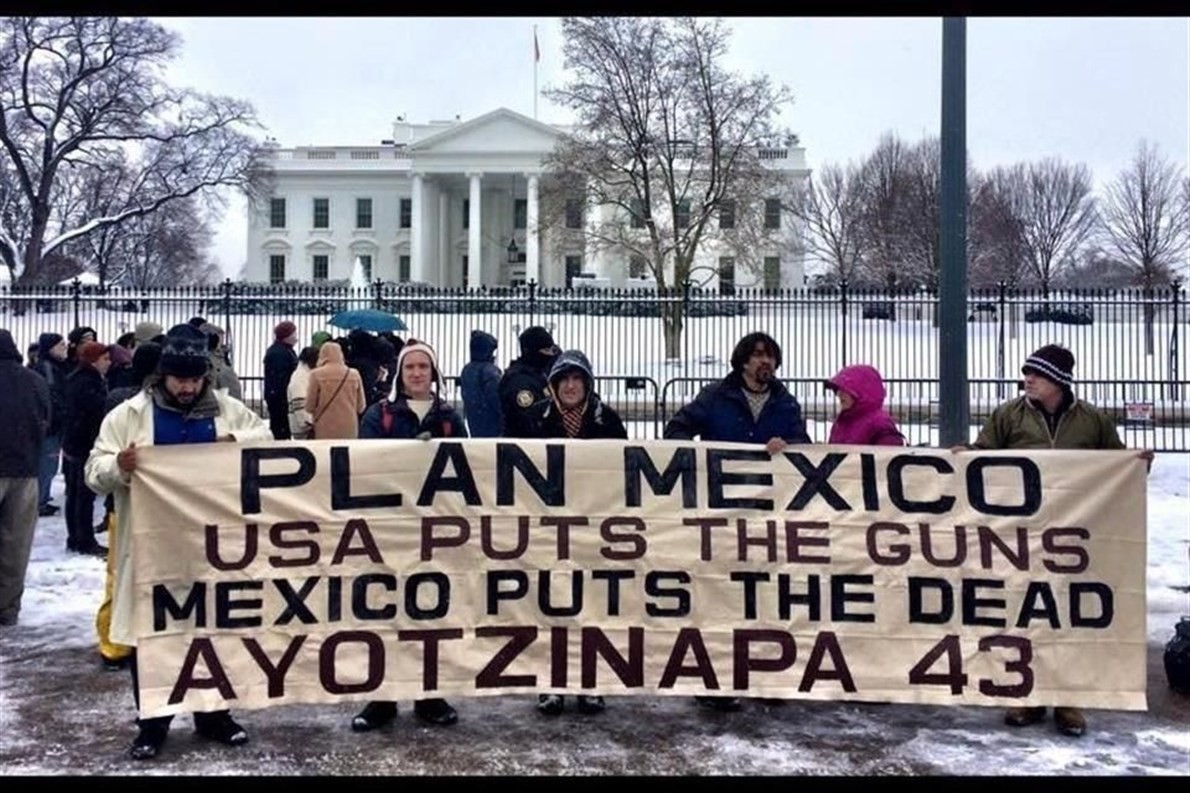

What eulogy can one write for a man like Javier Valdez? He wrote his own – it is his body of work and the ways he struggled, and died, for those he wrote about. We mourn by seeking to understand what it was he, and others like him, are trying to tell us about the nature of the drug war. We mourn by reading about the 43 students disappeared by the Mexican state.

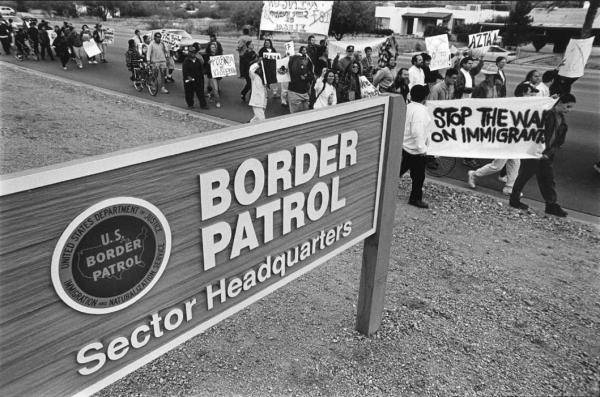

The last dispatch discussed the business of border enforcement and the for-profit incarceration of undocumented communities. Now we must look at the ways that cartel business does not end at the border line. Border Patrol, federales, and cartels should not necessarily be considered mutually exclusive entities. A lot of money and arms are flowing south to shore up government and cartel interests, and these interests are often exquisitely intertwined.

An instructive example of the blurred lines between those on the government and cartel payrolls is offered by the case of Border Patrol Agent Abel Canales. Canales was involved in the shooting of Jesús Enrique Castro Romo in November of 2010. Castro survived and sued over the incident. Canales was indicted in 2011 and accused of accepting a bribe in October 2008 to allow vehicles with drugs and/or undocumented migrants to pass through the Border Patrol checkpoint on Interstate 19. This is not a case of a “bad apple.” This agent was in the field with a gun, and all its associated immunity, two years after investigators witnessed him taking bribes.

These kinds of formal charges are only a shadow of the actual level of “corruption” taking place in the border region. Corruption itself as a term should be questioned because something can only be corrupt in relation to a code of ethical behavior which is actually upheld. Collaboration between different state/border enforcers and cartel workers, police, and paramilitaries happens with such frequency that it can be considered “corruption” only in the eyes of a misinformed public.

In the 2009 book Drug War Zone: Frontline Dispatches from the Streets of El Paso and Juarez, Howard Campbell unpacks the term cartel.

Transportation routes and territories controlled by specific cartels in collusion with the police, military and government officials are known as plazas. Control of a plaza gives the drug lord and police commander of an area the power to charge less-powerful traffickers tolls, known as pesos. Generally, one main cartel dominates a plaza at any given time, although this control is often contested or subverted by internal conflict, may be disputed among several groups, and is subject to rapid change. Attempts by rival cartels to ship drugs through a plaza or take over a plaza controlled by their enemies [have] led to much of the recent violence in Mexico. The cartel that has the most power in a particular plaza receives police or military protections for its drug shipments. Authorities provide official documentation for loaded airplanes, freight trucks, and cars and allow traffickers to pass freely through airports, and landing strips, freeway toll roads and desert highways, and checkpoints and border crossings.

Typically, a cartel purchases the loyalty of the head of the federal police or the military commander in a particular district. This official provides officers or soldiers to physically protect drug loads in transit or in storage facilities, in some cases to serve as bodyguards to high-level cartel members. Police on the cartel payroll intimidate, kidnap, or murder opponents of the organization, although they may also extort large payments from the cartel with which they are associated. Additionally cartel members establish relationships [or] connections with state governors or mayors of major cities, high-ranking officials in federal law enforcement, military, and naval officers and commanders and other powerful politicians and bureaucrats. These national connections facilitate the use of transportation routes and control of a given plaza.

If this is how the drug business functions in Mexico, what possible reason do we have for believing that it does not function in a similar manner in the borderlands? The US government’s own 2016 investigative inquiry has found corruption in the Border Patrol widespread enough to pose a “national security threat.” Whether or not Border Patrol agents have official cartel affiliations, the military culture of the organization offers them the same impunity to kill without consequence that the cartels further south enjoy.

The number of people killed by the Border Patrol is too long to review case-by-case: there are lists. The estimated number is 46 people since 2010. Examining the aftermath of these deaths, we see a pattern of impunity. Even incidents that get captured on tape, like the 2010 Border Patrol beating death of Anastacio Hernandez Rojas, do not result in charges. When charges are brought, convictions are illusive.

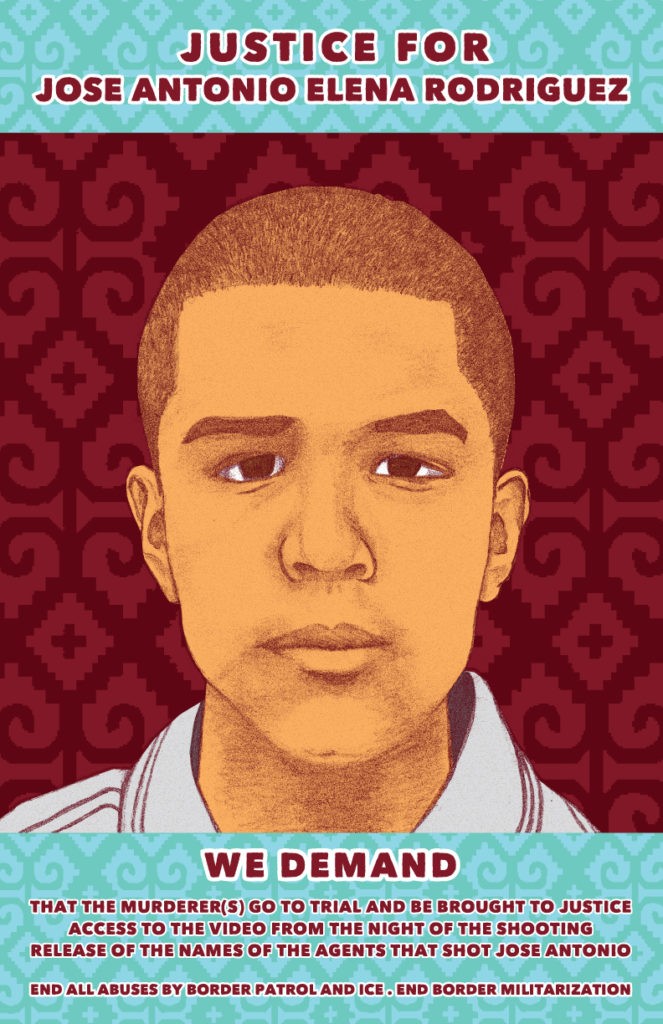

A case worth following is that of José Antonio Elena Rodríguez. In 2012, Border Patrol Agent Lonnie Swartz shot and killed 16-year-old José in the back at least 10 times as he was walking along the border wall in Nogales, Sonora. Two of the three volleys of shots hit him as he lay on the ground not moving. The trial of agent Swartz will begin in October. The BP claims that José was throwing rocks are not substantiated by witnesses. The defense has gone to great lengths to argue that the video of the event cannot be admitted as evidence because it is a copy of the original footage that the Border Patrol “lost” – i.e. destroyed.

A case worth following is that of José Antonio Elena Rodríguez. In 2012, Border Patrol Agent Lonnie Swartz shot and killed 16-year-old José in the back at least 10 times as he was walking along the border wall in Nogales, Sonora. Two of the three volleys of shots hit him as he lay on the ground not moving. The trial of agent Swartz will begin in October. The BP claims that José was throwing rocks are not substantiated by witnesses. The defense has gone to great lengths to argue that the video of the event cannot be admitted as evidence because it is a copy of the original footage that the Border Patrol “lost” – i.e. destroyed.

How the Elena Rodríguez case plays out will be affected by a previous case working its way through the courts right now. The civil case brought by the family of 15-year-old Sergio Adrián Hernández Güereca, who was shot in 2010 by Border Patrol Agent Jesus Mesa Jr., is set to determine the ability to sue when agents kill by firing from the US into Mexican soil. This case will be key in determining if constitutional protections apply to non-citizens.

At the heart of it is that so far no Border Patrol agent has ever been held legally responsible for any execution of a migrant, or resident, in the borderlands. Two Border Patrol agents are still on the job in San Diego after coercing 16-year-old Cruz Marcelino Velázquez Acevedo to drink liquid methamphetamine in 2014, killing him. In March of this year, the US government paid his family $1 million and the agents were never disciplined. The Border Patrol practices methods of sexual assault and torture, with the goal of inspiring widespread fear, in much the same way cartels do. It’s worth asking – are covert cartel links really even that important in understanding the role of border enforcers?

The Border Patrol is essentially the armed wing of the US government protecting the business of cartels and other border profiteers through unspeakable acts of violence. The Border Patrol consolidates power through the control and movement of undocumented bodies and profits off of death and suffering, just like the cartels. The rigid lines drawn for the public are nothing but a propagandist’s illusion, though one that is used to funnel a lot of money into Mexico.

One of the ways that money is flowing into Mexico to “fight the drug war” is through the Mérida Initiative. The Mérida Initiative is a security cooperation agreement between the United States, Mexico, and Central America through which the US provides training, equipment, and intelligence to combat “drug trafficking.”

How are Mexican institutions being “strengthened” under the Mérida Initiative? According to the US State Department website, Mexican institutions are strengthened by the following:

The United States is supporting Mexico’s implementation of comprehensive justice sector reforms through the training of justice sector personnel including police, prosecutors, and defenders, correction systems development, judicial exchanges, and partnerships between Mexican and U.S. law schools.

This kind of partnering hides violent social controls behind nation-building. The US has been widely criticized for training military and paramilitary forces in Mexico in the use of torture. In early July 2008, a video came to light of the city police from León, Guanajuato being taught torture techniques by an instructor from a US security firm. The training took place in April 2006 and after the public outcry over the incident the program was suspended.

Torture tactics taught by US security firms are used by the police and military in Mexico, yet somehow more funding, training and strengthening the “rule of law” is supposed to lead to less, not more, state violence. Once again a narrative of strengthening democracy and rights is being used to whitewash what is simply an outsourced version of the School of the Americas (SOA). Violence is justified just as often through ‘anti-corruption,’ institution building, and human rights discourses as through the more explicit narratives of war.

How well does US-led counterinsurgency training work as far as shoring up the institution of Mexican democracy? The ascension of the Zeta cartel provides a useful historical example. Los Zetas were founded in 1999 when commandos of the Mexican Army’s elite force, trained by the US Army’s 7th Special Forces Group at Fort Bragg’s School of the Americas, deserted to work for the armed wing of the Gulf Cartel.

In February 2010, Los Zetas broke away from the Gulf Cartel to form their own organization, “attacking Gulf operatives wherever they found them and claiming the turf for themselves. The Gulf Cartel allied with their old Sinaloan rivals to fight back, engulfing the region in violence.”

Such shifts in allegiances have to be understood in a context where the “drug war” is a business first and foremost. Commitments follow profit margins more than nation-state interests, and cartels, police, federales, military, and paramilitary roles can overlap, shift, and change with frequency. These changes in cartel power are then used to support the idea that there is a “narco-insurgency” at hand. What does this narco-insurgency narrative mean for policy? Narco-violence as a “new” ascending form of terrorism is being used to justify more border infrastructure, more agents on the ground, more internal controls, and more partnering with Mexico to fight against the cartels.

Counterinsurgency is needed to fight the narco-insurgency, which threatens the power of the state so skillfully because cartels like the Zetas were trained by the US in counterinsurgency. Fighting the narco-insurgency is the perfect excuse for maintaining the narco-insurgency.

This circular logic has us preparing for a boom in Border Patrol hiring. There is no indication that the next hiring surge of Border Patrol agents will change their culture of cruelty. Yet they continue to pretend as if they are saving people’s lives. Firstly, the Border Patrol doesn’t always respond when asked to search for missing migrants. More to the point, their enforcement methods kill people. There is a direct link between their tactics of apprehension and death and injury in the desert. The Border Patrol has total impunity to kill our loved ones and then through the mechanisms of media propaganda, blame them for their own death by painting them with a wide brush of criminality.

Things in the interior of the US are not looking any better. ICE officers are being told to take action against any and all undocumented immigrants while on duty. People are reasonably afraid to go claim their kids who are in custody lest it lead to their own deportation. Despite the fact that there is no link between increased immigration and crime rates, the fear mongering continues. Total criminalization has arrived in Arizona with a marked increase in the prosecution of first-time offenders and promises to charge everyone who is caught crossing with misdemeanors and felonies.

In times like this, we have to hold onto each other and to the idea that we can fight back. A shout out is in order to the teenagers who showed up in quinceañera regalia to protest SB 4 in Texas and to the undocumented attorney in New York who won his client’s asylum case. California is considering bucking national trends by passing a state law that would end their 287(g) agreements, stipulating local police cooperation with ICE, and not allow police to be deputized to check immigration.

There are reasons to be hopeful even in the midst of deep despair. Now that memories are all we have of our loved ones, the totality of what we have lost becomes concrete – heavy and weighted. But we must not become entombed by our dead. This pain must lead to something purposeful – even if the circumstances seem so meaningless and the coroner’s reports are so heartbreaking.

We must stand up for the legacy of our loved ones. The insidious language of criminality and “justified” murder need not poison our spirit. We can find dignity in all of this if we allow ourselves to feel the rage in our grief and if we mourn together.

We are here to say, again and again – and as many times as we must – that our friends on the line, en route and further south did not deserve to die. They deserve to be remembered and fought for.

Further reading:

The Disappeared

Death on the Line

Committee to Protect Journalists

Further viewing:

Deadly Apprehension Methods

The Death of Javier Valdez