Filed under: International Coverage

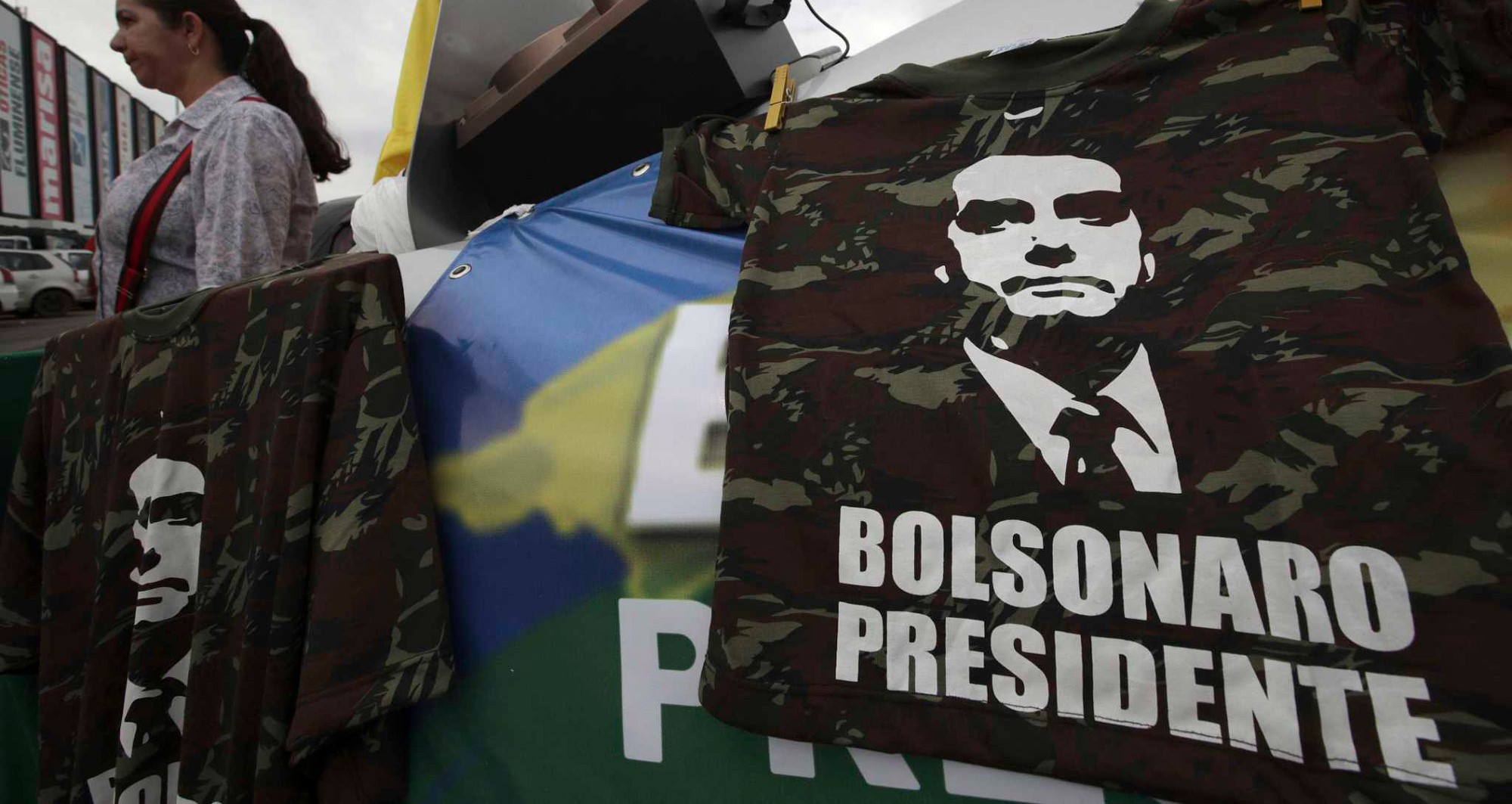

In Brazil, Jair Bolsonaro, fascist proponent of dictatorship and mass killings, has won the election. Who needs a military coup when you use voting to accomplish exactly the same thing? We’ve already explored in detail how the left and centrist parties paved the way for this. From Brazil to France, parties across the political spectrum have lost all pretense of offering any solution to social problems other than escalating state violence. In this context, it’s not surprising that politicians who explicitly represent the police and military are coming to power, as they have become the linchpin of the state itself.

Our hearts go out to our comrades in Brazil, who have already experienced a tremendous amount of state repression and capitalist violence—and will now face far worse. Perhaps the immediate resistance that greeted the election of Donald Trump can serve as a useful reference point. Yet because of the specific ways Brazil is on the receiving end of colonialist violence, the wave of nationalism that has already crested in the United States and Europe will involve considerably more brutal violence there. We call on everyone around the world to prepare to mobilize in solidarity with those who are targeted in the attacks that Bolsonaro has promised to carry out.

As anarchists, we don’t believe that elections grant legitimacy to any ruling party. No election could legitimize police violence, homophobia, racism, or misogyny in our eyes, nor prisons, borders, or the destruction of the natural world on which everyone’s survival depends. No vote could give a mandate to anyone who wants to dominate others. Majority rule is as repugnant to us as dictatorship: both make coercion the fundamental basis of politics.

The important question is not how to improve democracy; fundamentally, democracy is a means of legitimizing governments so that people will accept their impositions, no matter how tyrannical and oppressive those may be. The important question is how to defend each other from the violence of the state; how to find ways to meet our needs that don’t depend on unanimity or coercion; how to collaborate and coexist rather than competing for power. As more and more oppressive regimes take power around the world, we have to have done with our illusions about “good” democratic government and organize to protect each other by any means necessary.

The opposite of fascism is not democracy. The opposition of fascism is freedom; it is solidarity; it is direct action; it is resistance. But it is not democracy. Democracy, yet again, has been the mechanism that brought fascists to power.

Students at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro demonstrate against police raids carried out ahead of the election. The police confiscated posters proclaiming “Jewish students against fascism” and depicting murdered activist Marielle Franco.

Click the image to download From Democracy to Freedom in Portuguese.

Click the image to download From Democracy to Freedom in Portuguese.

Click the image to download From Democracy to Freedom in Greek. This is the first chapter of the book; other chapters have been translated, but are not yet available.

You can order the German translation of From Democracy to Freedomhere. You can download a draft version of the first chapter in PDF form here.

You can order the German translation of From Democracy to Freedomhere. You can download a draft version of the first chapter in PDF form here.

Epilogue from the German Publishers

Before this book was published, we presented discussions about democracy together with comrades from the US and Slovenia in autonomous centers around Germany. Although none of the texts in From Democracy to Freedom explicitly deals with the situation in Germany, that does not mean that we have not had quite similar experiences—on the contrary.

The State

A few weeks before the federal election in 2017, a propaganda truck was driving around on behalf of the Bundestag, the German federal parliament. They were distributing baseball caps and candies featuring the Bundesadler, the coat of arms of the Weimar Republic (which is back in service to today’s German government), as well as propaganda films for students about parliamentary democracy. The organizers emphasized how democratic Germany is. This sort of advertising offensive was obviously necessary for a system that has good reason to fear for its own legitimacy.

The Parties

All parties represented in the Bundestag claim that democracy as one of their central issues. The SPD wants to risk trying more democracy, like Willy Brandt said; the Green party wants to expand democracy; the Left just wants more democracy; Christian Democrats want to strengthen democracy; liberals want to revive democracy; and the racist, neo-fascist AfD presents itself as a party for direct democracy. The entry of the AfD into parliament confirms once again that advocacy for direct democracy is hardly a guarantee of emancipatory politics.

Whatever we do, whatever we demand, we should always make sure to emphasize why we are struggling, so as to protect our ideas and rhetoric from appropriation by conservative or fascist groups who fight for the exact opposite of what we are fighting for.

“Civil Society”

Those who pursue initiatives for “more” or “real” democracy like to present themselves as courageous or even revolutionary fighters against the prevailing political order—when in fact, they only want another kind of representation. Conferences with names such as “Democracy Needs Movement” are an example of this development. As people who express ourselves uncompromisingly against any form of democracy, we nevertheless spoke there; people raised their eyebrows at us because our positions and goals cannot be implemented in the context of a better democracy.

For many, it is impossible to imagine that there could be anything else. This is one of the problems with democracy: it narrows down what we can imagine.

The Movement

In anti-capitalist struggles in Berlin, we met people who appeared to believe that making signs with their hands during meetings represented the epitome of revolutionary behavior. Some people told us that the methods of communication and decision-making should take priority over the results. Some didn’t see it as a problem that their chosen form of decision-making resulted in the permanent obstruction of any meaningful form of activity.

All this, because for the first time in their lives, they understood themselves as an important part of an apparatus. We were expected not to destroy this feeling of finally getting it right. We did it anyway.

We tried to adapt to the proposed rules of “non-violent activists” in order to be able to cooperate with them. In the process of making decisions with them, we used the right of veto to block a decision that seemed intolerable to us. We discovered that our veto was less important than other people’s veto. In the end, we had to discuss whether there could be a veto against our veto.

Once again, we saw that the official methods of decision-making only last as long as they serve the interests of those who introduced them.

When we were part of the discussions preparing the blockading actions at the G20 summit, we decided to be strategic: we sat in different positions in the meetings, we split up into different working groups. We did this to prevent worse attempts at manipulation, to block authoritarian attempts to control the process from the very beginning, to influence the discourse. Doing this, we learned something about our own power potential—and it scared us. We saw that we could play this game too: we knew the mechanisms and we could play the same tricks. We knew how and when to formulate a question if we wanted to be the ones who determine how the discussion would go—how to fix the order of the points on the agenda—when to set the start time of a meeting. Sometimes we were not just afraid of ourselves, but also disgusted—because on the way to overthrowing all authority, we were tempted simply to seek to get our own piece of the cake.

This experience gives us all the more reason to be critical of the democratic framework.

We have not only encountered the debate about democracy in practical struggles on the street. We can also find it in a few theoretical texts from German-speaking countries. We can recommend two such publications here:

Christoph Spehr, Die Aliens sind unter uns. Herrschaft und Befreiung im demokratischen Zeitalter

Jörg Bergstedt, Demokratie. Die Herrschaft des Volkes. Eine Abrechnung