Filed under: Analysis, Featured, Immigration, Incarceration, The State, White Supremacy

With the growing debate over Trump’s policy of terror directed towards migrants and the appropriate use of the term “concentration camp,” it’s important to place what’s happening today within the context of U.S and colonial history.

By Tariq Khan, Julia Tanenbaum, and Cole RS

Recently some mainstream news and commentary outlets have posted a number of pieces which correctly label US migrant-detention centers as concentration camps. Of note are recent pieces in the Los Angeles Times, “Call immigrant detention centers what they really are: concentration camps,” and Esquire, “An Expert on Concentration Camps Says That’s Exactly What the U.S. Is Running at the Border.” Following these pieces, US Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez commented on Twitter: “This administration has established concentration camps on the southern border of the United States for immigrants, where they are being brutalized with dehumanizing conditions and dying. This is not hyperbole. It is the conclusion of expert analysis.”

Likewise in an Instagram video AOC called the Trump administration “authoritarian and fascist,” and explained: “I don’t use those words lightly. I don’t use those words to just throw bombs. I use that word because that is what an administration that creates concentration camps is. A presidency that creates concentration camps is fascist.”

In turn Republicans responded to Ocasio-Cortez’s comments with the same style of disingenuous outrage, oversimplification, and obfuscation that they always do. But this time the right wing had backing – a cacophony of liberal hand wringers and pearl clutchers took to social media to explain to the left that “concentration camp” isn’t really the appropriate term. After all, while albeit imperfect, this is the democratic United States, they lectured us, not Nazi Germany.

Even Bernie Sanders capitulated to the right-wing fake outrage and the ahistorical liberal “well actually” lecturing. On CNN, Erin Burnett asked Sanders, “Are you comfortable calling detention of migrants on the Mexican border concentration camps?” Sanders responded, “I didn’t use that terminology.” As he hedged the question, trying to ride the fence with phrases such as “comprehensive immigration reform,” and “path toward citizenship.” Burnett again pressed, “But you don’t use the word concentration camps?,” to which Sanders responded, “No, I have not used that word.” Given the fact that “concentration camp” is an accurate description of what those detention camps are, Sanders’ refusal to use the term can be seen as nothing less than cowardly.

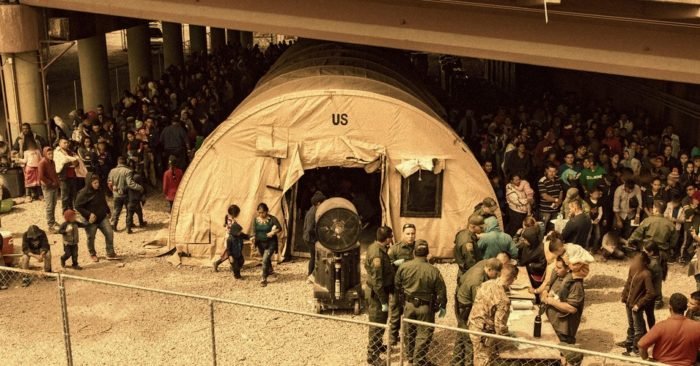

U.S. concentration camp: 1862 or 2019?

U.S. concentration camp: 1862 or 2019?

The Origins of “Concentration Camps”

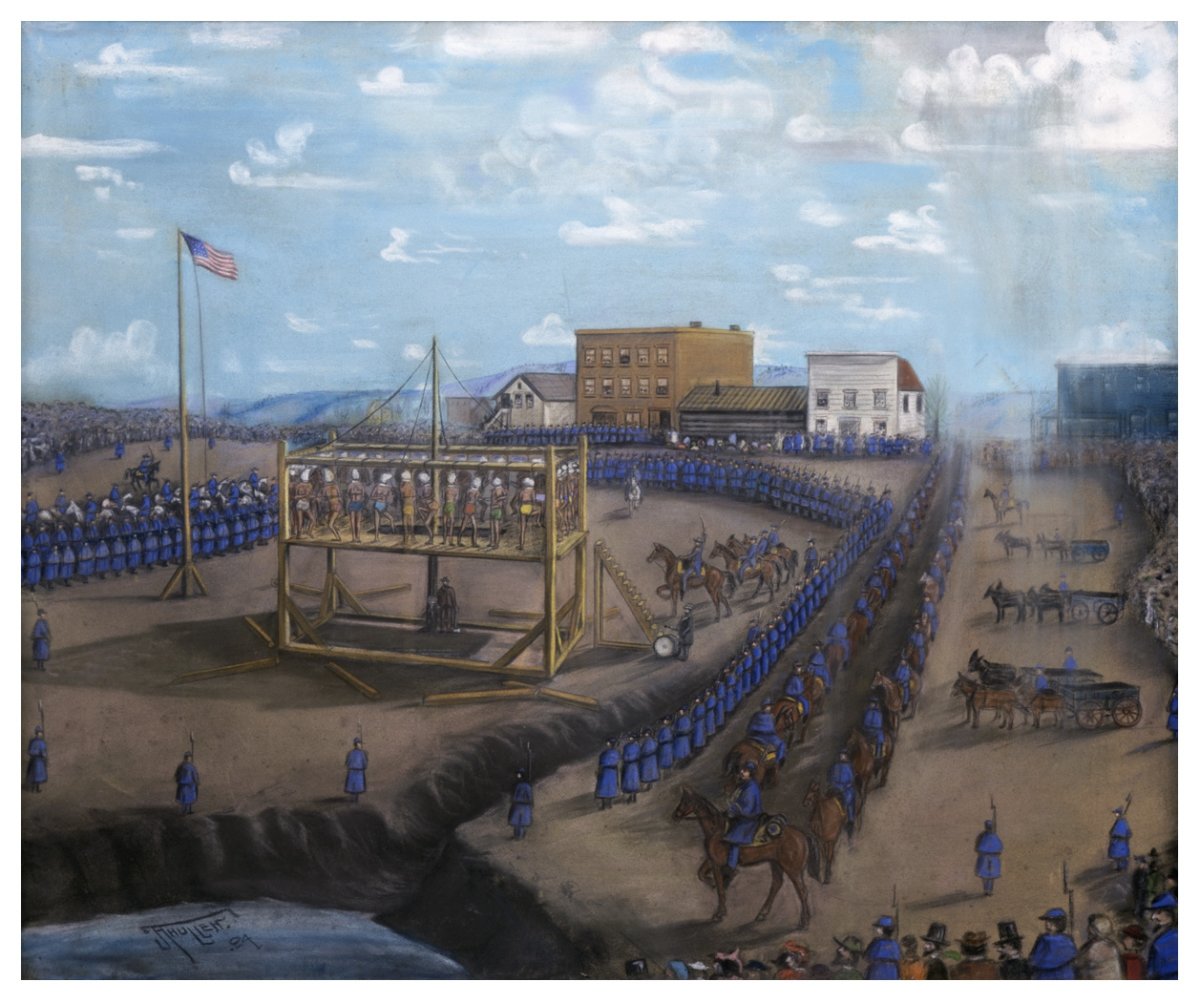

Concentration camps originated as a weapon of US/European colonial control first directed against Native peoples as part of a larger strategy of genocide – a process which we now call settler colonization. In 1862 the US Army rounded up hundreds of Dakota Sioux people into concentration camps in Minnesota as part of a campaign of genocide. In a special legislative session on September 9, 1862, Minnesota Governor Alexander Ramsey said to his colleagues, “Our course then is plain. The Sioux Indians of Minnesota must be exterminated or driven forever beyond the borders of Minnesota.” US Army regulars and civilian settler vigilantes worked together to slaughter Dakota Sioux people and round others up into concentration camps, culminating with US President Abraham Lincoln ordering the hanging of 38 Dakota men in a mass execution. The remaining Sioux people in the area were then expelled or confined to reservations. US officials placed a bounty on Dakota scalps, thereby incentivizing ordinary white settlers to murder Dakota people who remained in the area.

The British and the Germans, informed in part by the settler colonizer strategies of the US, applied these same techniques of colonial control in British South Africa and German South West Africa. Concentration camps were a significant weapon the German Empire used in its genocide against the Herero and Namaqua peoples from 1904-1908. During the genocide, colonial officials forced Herero women to work in concentration camps scraping the flesh from the bones of Herero corpses to prepare the bones for shipping to European and US museums. Some of these Herero skulls still reside in the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.

The actual term “concentration camp” comes directly out of European colonialism in the Americas with the term first used by the Spanish colonizers of Cuba in 1897. Overseeing Spanish colonialism in Cuba and the Philippines was General Valeriano Weyler who first applied the term (reconcentrados) to his tactic of containing anti-Spanish insurgents in Cuba. While he gave the practice a name, he was not the first to use the tactic. He learned the tactic from studying US genocider General William Tecumseh Sherman’s campaigns against the Indigenous peoples of the Great Plains. The term itself is, therefore, directly connected to the United States’ own history of ethnic cleansing and “frontier” control.

The Present Discourse of Historical Amnesia

The Present Discourse of Historical Amnesia

In present US public discourse, the term “concentration camp” evokes only a particular and unique tragedy of Nazi death camps precisely because the US state requires the erasure of its own genocidal settler colonization to maintain the illusion of legitimacy. Genocide then becomes something that those Nazis did to Jews in that one case far away, not something that is part of the foundation of the United States itself – and certainly not something that could still be part of US policy. A core of US liberal ideology is that fascism is incompatible with democracy and individual rights, and therefore the United States could not possibly be doing the same kinds of things European fascists did. Further, say the liberals, to even compare US policy with Nazi policy is a slap in the face to the victims of the Nazi Holocaust.

The Jewish Community Relations Council (JCRC) of New York condemned the use of “terminology evocative of the Holocaust to voice concerns about contemporary political issues.” This reading of the Holocaust asserts that its horrors are incomparable and is a naked effort to police the boundaries of memory itself. Yet, historical trauma also inspires solidarity. As survivors and their descendents wrote in a letter protesting the 2014 bombing of Gaza, “Never again’ must mean NEVER AGAIN FOR ANYONE!” The longstanding Jewish socialist organization the Workmen’s Circle responded to the JCRC statement by declaring “Never Again must now inspire rather than divide us.” Young Jewish antifascists like the members of Outlive Them are pushing back against institutions that silence their voices. The group is putting out a call this weekend to other Jews to break with the politics of divide and conquer displayed by organizations like the JCRC and reflecting the frustration and hurt of many members of the community, particularly Jews of color whose voices are ignored by the community’s establishment.

The Colonial Context of Concentration Camps

The refusal to use the honest descriptive terminology is a product of profound misunderstandings about what the United States is and how it developed as well as misunderstandings of what fascism is. In the classic essay Discourse on Colonialism, the anticolonial poet Aimé Césaire observes that the cruel, modern, rational brutality of Nazism was not an aberration from what Europe was, but rather it was the accepted way Europe treated the Black and brown peoples of its colonies. Concentration camps and genocide were not new. They were developed through colonialism for controlling, containing, expelling, and exterminating “savages” well before the Nazis turned them against “undesirables” within the metropole. Anti-imperialist scholar Zac Cope similarly writes that “Geographically speaking, on its own soil fascism is imperialist repression turned inward…” In conversation with Césaire and Cope, anticolonial Indigenous writer Ena͞emaehkiw Wākecānāpaew Kesīqnaeh writes:

“In the case of the north amerikan settler colony, the sense of exteriority inherent in Césaire’s description of the perfection of what would become fascist oppression within the deployment of colonial violence overseas becomes interior. While for Césaire and Cope the violence of fascism is brought home from the distant colonies of the metropolitan imperialist powers, in the settler colonial context this violence is one that was perfected within the exceptional state of the expansion of the frontier, the clearing and civilizing of Indigenous People to make the land ripe for settlement, and the carceral continuum that has marked Black existence on this land from chattel slavery to the modern hyperghetto.”

Concentration camps are historically part of what the United States is. They were employed by Bernie Sanders’ favorite US president FDR against Japanese people in the United States in the 1940s. Indeed, Trump’s present day migrant concentration camps stem from the legacy of FDR just as much as Sanders’ social democratic policy proposals do. But FDR himself was not at all original in using concentration camps to contain “undesirables.” He drew on the legacy of US “frontier” control, and it is that settler colonial context that applies directly to the migrant concentration camps of the present. Nothing symbolizes this truth as clearly as Fort Sill, a US military base currently caging migrants that was built specifically to wage genocide against Indigenous nations in the eighteenth century. It was the site of imprisonment for hundreds of Apache people, including Geronimo, and would later become a Japanese internment camp in the mid-twentieth century.

As Palestinian intellectual Steven Salaita remarked:

“The border on either side of the United States isn’t natural topography; it’s a foreign imposition sanctified by theft and ethnic cleansing. The border bisects dozens of nations that long predate the United States and do not recognize its authority. Many of the people traveling from South and Central America are Indigenous and thus operating within their own hemispheric milieu. The separation of families and the Muslim ban demolish any pretense of sovereignty by preventing Native nations from applying their own policies on refuge and migration. Beware the type of resistance that legitimizes the United States as steward of its borders and the international territories they constrict.”

Mass execution of 38 Dakota man at Mankato, Minnesota.

Mass execution of 38 Dakota man at Mankato, Minnesota.

Names Matter And So Does Our Response

The current US system of migrant detention is undoubtedly a system of concentration camps. It is not an aberration from what the United States is, but rather is an expression of what the United States, as a genocidal settler colonizer state, has always been since the Declaration of Independence termed Indigenous people “merciless Indian savages.” It is a continuation of US “frontier” racism and brutality.

Even on the surface level there are far too many similarities to just brush aside — even with Nazi concentration camps in the earlier stages — from the taking of people’s jewelry, to the creation of specific camps for people whose gender and sexuality fall outside the desired norm. It is no coincidence the first time this administration recognized trans and non-binary people it was in the context of detaining them.

More importantly, on a structural level they serve the same function. These camps serve to isolate, contain, disappear, and expel a supposedly undesirable population. They are not “like” concentration camps. They are concentration camps. We cannot accept the state’s narrative, which serves only to cloud truth and perpetuate injustice. It matters to call them concentration camps, and to understand that concentration camps are part of the colonialist DNA of the United States, because that affects the way and the level of urgency with which we respond to and resist this racist system of state terror. We cannot be distracted by a veneer of decency; instead we must understand and confront the material reality of the US state.