Filed under: Anti-fascist, Editorials, US, White Supremacy

As fascist groups and the Klan gain new ground through the insurgence of white supremacist organizing amid the Trump campaign umbrella, antifascist and anti-Klan mass mobilizations have drawn more thousands of participants from Seattle, Washington, to Stone Mountain, Georgia, to Sacramento, California. Yet these altercations often turn violent, with unprepared protesters often suffering stabbings and beatings. It is instructive to look back on the recent history of antifascist and anti-Klan movements in the US to better mobilize effectively against the rising tide of white supremacy within local communities, thus pre-empting fascist groups’ ability to build forces.

The Legacy of Greensboro

The “Death to the Klan” slogan emerged prominently during the 1970s, while the Knights of the Klan spread throughout the US, leading to a further expansion of other Klan groups like Invisible Empire. The Klan’s new wave of organizing played a significant role in Southern communities like Greensboro, North Carolina. A left-wing group called the Communist Workers’ Party organized militant, anti-racist opposition to the Klan in 1979. For those organizing around community defense today, the legacy of Greensboro looms large. Its history offers important reference points for mobilizing against the rising insurgency of racist violence, both political and social.

The CWP (then the Workers’ Viewpoint Organization) spun off of the Progressive Labor Party (PLP) as part of the New Communist Movement of the 1970s. Their practice of organizing within textile unions yielded positive results both in workplaces and against racism in the broader community. However, the emergent Klan presented a significant challenge to their organizing. In July, the CWP “took the fight to the Klan” in the neighboring town of China Grove, disrupting a Klan-organized viewing of The Birth of the Nation and burning a confederate flag outside. Klansmen drew on the protesters, but stood down. The CWP opinion on the action was that of a huge “psychological victory.”

The sense of urgency surrounding community defense grew stronger, and the CWP became increasingly militant, emboldened by their successes. On November 3rd, 1979, the CWP called for a demonstration entitled, “Death to the Klan.” Their propaganda declared, “We invite these two-bit punks to come out on Nov. 3rd and face the wrath of the people.” They circulated an open letter to the rival Klan leaders stating, “We are having a march and conference on November 3, 1979, to further expose your cowardness, why the Klan is so consciously being promoted and to organize to physically smash the racist KKK whenever it rears its ugly head.”[1]

An FBI informant embedded in the Klan phoned the district attorney’s office with new information. A coalition of racist groups uniting as the United Racist Front planned to launch an armed assault on the demonstration. The informant implored the attorney general to rescind the permit for the Death to the Klan demonstration, but the warning went unheeded. Three days before the rally, the informant went to the police station with the same information, but again met a dismissive response. The police told the informant to stay away from the bloodshed, and he replied that the Klansmen would identify him as an informant if he did. “The next time I ask you do to something,” he retorted, “I’ll bring a bucket of blood.”[2]

As the protesters gathered with placards on a remarkably warm day for November 3rd, they burned an effigy of a Klansman, and chanted “Death to the Klan!” Local Neo-Nazis drove to the anti-Klan protest in a nine car caravan together with Harold Covington’s National Socialist White People’s Party. The United Racist Front caravan was joined by at least two FBI and police informants. When they arrived, several cars slowly cruised past the protest as members of the CWP chanted “Death to the Klan” and challenged the passengers to come out of their cars. A blue sedan followed by a yellow van parked less than fifty yards away from the protest. The passengers got out, took sidearms and rifles out of the trunk, and opened fire for about a minute and a half. Two CWP members and three march participants were killed by the Klan on that day, which would go down in workers’ history as the Greensboro Massacre.

As the protesters gathered with placards on a remarkably warm day for November 3rd, they burned an effigy of a Klansman, and chanted “Death to the Klan!” Local Neo-Nazis drove to the anti-Klan protest in a nine car caravan together with Harold Covington’s National Socialist White People’s Party. The United Racist Front caravan was joined by at least two FBI and police informants. When they arrived, several cars slowly cruised past the protest as members of the CWP chanted “Death to the Klan” and challenged the passengers to come out of their cars. A blue sedan followed by a yellow van parked less than fifty yards away from the protest. The passengers got out, took sidearms and rifles out of the trunk, and opened fire for about a minute and a half. Two CWP members and three march participants were killed by the Klan on that day, which would go down in workers’ history as the Greensboro Massacre.

The community was horrified, but also partly confused. Despite knowing in advance about the attack, police had taken a lunch break and were nowhere by the scene, raising suspicions as to their intentions. Reeling from the massacre, the group’s leadership fell under heavy criticism, not only from the police and mayor, but also from other radicals. One group called Concerned Citizens wrote the following harsh critique:

It was utterly stupid and irresponsible for the Workers Viewpoint Organization [CWP] to challenge the Klan and to invite them into the Black community in the way that they did. It was totally irresponsible for them, having dared the Klan to come, to take no effective measures to protect and defend not only themselves, but the community where their demonstration took place. These adventuristic and irresponsible actions not only allowed the murders of their own people to take place but endangered innocent people, including children and old people. Their statements and actions since are almost insane. They seem only interested in avenging the murders of their own people and portraying what happened as a fight between them and the Klan. They have refused to work with anyone to build a broad response by the entire Black community, which is what is urgently needed.[3]

Concerned Citizens insisted that by promoting themselves as anti-Klan fighters, the CWP effectively moved the spotlight away from the general harassment of the Black community by the Klan, and placed it on themselves. In a withering analysis, the Amilcar Cabral/Paul Robeson Collective joined the Greensboro Collective in declaring, that the “most striking” lesson learned “is the damage ultra-leftism does to the mass movement. The actions of the CWP after November 3rd were nearly as effective in preventing the masses from taking militant action as the CWP’s actions before November 3rd had been in achieving their murders.” The collectives continued, “[The CWP] were amazingly able to achieve a situation by the middle of the week after the Massacre, where they were seen by the masses as almost as big a danger, if not bigger, than the Klan.” The text resolved that, “Ideological preparation without self-defense would be criminal on the part of revolutionaries and suicide for black people.”[4]

The criticism for the CWP had been harsh, and perhaps inflamed an already traumatic time. They would, however, pave the way for better methods of anti-Klan organizing, building on the CWP’s courage as well as their faults. Although an FBI informant and an ATF informant took part in the organizing of the attack, and the assailants were caught on video, no convictions came. One of the participants in the attack, Frazier Glenn Miller, would later join the network of an infamous white supremacist terrorist group known as the Order between 1983-1984 and kill three in a shooting outside of a Jewish recreation center in 2014. The year after the Greensboro Massacre, Neo-Nazi Harold Covington narrowly lost the Republican nomination for Attorney General of North Carolina. In perhaps the only silver lining of the atrocity, the aftermath of the Greensboro massacre led, in part, to the disintegration of the insurgent Knights of the Klan, since national leader David Duke looked at the violence as anathema to his political career, which he would pursue in Louisiana to varying degrees of success.

Death to the Klan, pt. 2

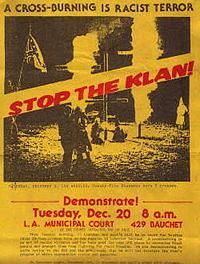

Despite the critiques of the WVO/CWP, the “Death to the Klan” chant became a national rallying cry when the recently-formed John Brown Anti-Klan Committee (JBAKC) published their first newsletter that month called Death to the Klan. Initially emerging out of the struggle against Klan organizing among prison guards by Black and Puerto Rican prisoners in New York, the JBAKC maintained ties to the New Afrikan People’s Organization and reported broadly on the Black liberation struggle, as well as Arab liberation struggles in Southwest Asia.

Despite the critiques of the WVO/CWP, the “Death to the Klan” chant became a national rallying cry when the recently-formed John Brown Anti-Klan Committee (JBAKC) published their first newsletter that month called Death to the Klan. Initially emerging out of the struggle against Klan organizing among prison guards by Black and Puerto Rican prisoners in New York, the JBAKC maintained ties to the New Afrikan People’s Organization and reported broadly on the Black liberation struggle, as well as Arab liberation struggles in Southwest Asia.

Death to the Klan registered in their first issue that on the day of the Greensboro Massacre, the Klan marched in Dallas, Texas, where they were met with 2,000 counter-protesters—mostly Black and Chicano/Mexicano/Tejanos. The Klan had to be picked up and bused “to the finish line” by police to avoid the demonstration. “The liberation of the Black nation will be the death of the Klan,” they wrote, extending solidarity to all victims of US imperialism.[5] If there was a lesson to be learned based on the contradiction between the brash rhetoric of the WVO and the grassroots mass organizing in Dallas, it would lie in a synthesis between community defense and mass organizing. According to Death to the Klan, it did not make much sense for non-white communities to march against the Klan, because everyone already knew they opposed the Klan. Self-defense remained imperative for non-whites. For white communities, on the other hand, rallying remained an important show of opposition, but self-defense remained largely misunderstood. Another group emerging at the time called the Prairie Fire Organizing Committee (PFOC) took a similar stance, having formed to spread the revolutionary ideology of the Weather Underground in 1975.

In the midst of the farm crisis in the early-to-mid-1980s, as the Klan began to join with Nazi skinheads emerging throughout the US in what PFOC’s newspaper Breakthrough called “the Chicago strategy,” JBAKC found it difficult to articulate a mass self-defense strategy.[6] When Graffiti began to appear around Chicago of Klansmen in robes, the JBAKC called for a movement to “stamp out racist graffiti,” which also extended to protesting the Klan. At one protest in Aetna Plaza, 60 anti-racist demonstrators faced 15 Klansmen and members of the skinhead gang Romantic Violence. Anti-racists pursued the racists, threw eggs, and surrounded them. However, racists armed with shields and weapons fought back, beating the unprepared protesters. I spoke with M. Treloar, one of the protesters who was there that day, and he told me that images of Greensboro flashed through his head as the Klansmen went to their trunks, and began to return with weapons:

[Protesters] surrounded the racists—there were only about 15 of them, but they came prepared with shields made of wood with razor blades imbedded in them, and other stuff, and they actually kind of knew how to fight. [T]he Nazis and Romantic Violence and the Klan attacked, and actually dispersed the crowd, because they basically didn’t know how to fight, and weren’t organized to fight. They then ran for their cars…, and those of us standing around were like, ‘Okay, they’ve gone to their cars. They’re getting stuff out of their trunks. Oh shit.’ That was exactly the scenario that happened in Greensboro.[7]

Only the intervention of the police at the last moment saved the demonstrators from a far more brutal outcome. “The confrontation at Aetna Plaza was a turning point in understanding what confronting the Klan in Chicago would mean,” an article in Breakthrough explained. “Throughout the winter and early spring, as the fascists continued their campaign, the anti-racist movement intensified its efforts to become a meaningful political force.”[8]

Anti-Racist Action

As the JBAKC and PFOC worked to overcome the lack of self-defense training exhibited at the 1985 Aetna Plaza protest, in Minneapolis, a racist skinhead group called the White Knights began to attempt to control the streets. Seeing the Knights as a racist threat to their community, an anti-racist skinhead crew called the Baldies rapidly organized to beat them back. Baldies co-founder Kieran Knutson explained the early tactics.

When the fascists got strong, they started to control things and also were a physical threat, especially to people of color, queer kids, and outspoken anti-racists in the scene, so in Minneapolis, that’s pretty much how it started. When we saw an individual White Knight, we would approach them and ask them if they were White Knights, and if they said yes, we’d say, ‘the next time we see you, if you’re still a White Knight, you’re going to get your ass kicked.’ It wasn’t a strategy that was come up with by any left group or activist, but it was a very smart tactic, because it let people think about it—to figure out if they really wanted to defend fascism or fascists, and a number of them quit, and a few came over.[9]

Pitched battles would take place between the Baldies and the Knights with the anti-racist skinheads firmly holding their ground, and sending the Knights packing. These early skinhead battles instilled confidence in a new generation of anti-racists who developed new strategies and tactics to confront white supremacy.

According to cofounder of the Baldies and current hip-hop MC Mic Crenshaw, “What was so important about the ‘80s, when we started to reach out to other cities outside of Minneapolis was building other relationships, and seeing that there were other black skinheads, that there were other Latino skinheads, that there were other people in our movement that weren’t white.”[10] With new racist skinhead groups forming throughout the Midwest, anti-racist groups mobilized and networked. The Baldies in Minneapolis joined with groups from Indiana, Ohio, Illinois, and elsewhere to form a decentralized organization called Anti-Racist Action (ARA).

The message of anti-racism would spread through traveling bands, movement newspapers and bulletins, and word of mouth. One of the earliest chapters, Toronto ARA invented new ways of exposing racists’ addresses and places of business to the public.[11] On one occasion, protesters were rapidly shuttled onto a passing streetcar from a protest convened in an area known to be close to notorious Nazi Ernst Zündel’s house, and taken to the home base of a racist hotline, where the actual protest ensued without the dangerous presence of fascist militants.[12] Insurgent journals like Arm the Spirit published these kinds of advanced tactics, while ARA’s efforts began to extend to defending abortion clinics, patients, and doctors from white supremacists aligned with the pro-life movement. However, this above-ground work carried high risks of violence, so a number of anti-racist activists armed themselves and took part in trainings and exercises in armed self-defense—particularly in Portland, Oregon, where a small army of fascist skinheads openly organized to spread hate and violence.

Armed Antifascist Community Defense in Portland

In the late-1980s, Portland was not known for the carefully curated liberal brand it boasts today. Born of racial exclusion laws, Portland’s almost entirely white, working class population had passively watched the brutal displacement of the black community of Albina during the 1970s. During the next decade, the large bohemian subculture viewed skinheads as yet another micro-subculture within the hard-bitten punk scene. Dozens of racist skinheads could converge on music venues to effectively control the mood, tempo, and atmosphere. They could also take over and disrupt social movement spaces, as well as organize gangs to fight street battles against anti-racists and people of color. However, the broader community of Portland did very little to challenge their existence, although the swastikas and racist graffiti scrawled throughout the city presented just as clear a racist message as the knots of skinheads hanging around Laurelhurst Park and downtown’s Pioneer Square.[13]

This dynamic changed, however, when members of skinhead gang East Side White Pride (ESWP) murdered an Ethiopian immigrant named Mulugeta Seraw outside of his apartment on SE 31st and Pine. The scandal that ensued implicated a white supremacist leader based outside of San Diego named Tom Metzger, who sought to unite skinheads under his organization, White Aryan Resistance (WAR). The former leader of the California branch of Duke’s Knights of the Klan, Metzger had associates in the Nazi Party, the Christian Identity movement, and the growing, autonomous skinhead movement. White Aryan Resistance embraced youth culture, and encouraged skinheads in disparate gangs across the US to organize into a federation that his leading attaché, a young skinhead named Dave Mazzella, called the “WARskins.” Helping to organize ESWP into a more politically solid group shortly before the Seraw murder, Mazzella became a key witness for the Southern Poverty Law Center, which along with Seraw’s family filed a massive, successful lawsuit against Metzger.

The lawsuit against Metzger heightened the tensions in the local skinhead movement. Metzger wanted to organize the skinheads into his “frontline” army and towards this end many skinheads converged on Portland as a place to join the fight. Coming from Chicago to Portland to avoid the pressures of organizing, M. Treloar found himself in the middle of an increasingly perilous national conflict:

Now, they didn’t start out armed in the same way that Hitler’s Nazi Party did not start out as the Wehrmacht. The Nazis in 1923 were just a bunch of Beerhall brawlers. They didn’t have tanks, they didn’t have aircraft, they didn’t have machine-guns. The early Portland punks; they killed Mulugeta Seraw with baseball bats, but three years later when they were trying to track us down, they had AK-47s, .38s, knives, etc. So they progressed rapidly, and that, at least to a certain extent, I believe, wasn’t Nazi influence on the Internet (which really didn’t exist then, but was just coming into being), but was neo-Nazi influence that was coming out of California. That is, White Aryan Resistance, Tom Metzger’s group, as well as some of the stuff that people learned by going to national gatherings.[14]

Soon, organized anti-racist gangs like the Red and Anarchist SkinHeads (RASH) and the SkinHeads Against Racial Prejudice (SHARPs) found themselves in frequent battles with neo-fascists converging on Portland. A group called Coalition for Human Dignity (CHD) activated not just to beat back the onslaught of skinheads, but to transform racial consciousness in Portland. They used the strategies developed by ARA to expose and shame skinheads wherever they showed their faces, getting them fired from their jobs and evicted from their apartments. However, when skinheads began to harass local members of the community, attacking their houses and cars, CHD devised a decentralized community self-defense strategy.

The catalyst came after anti-racists heckled a racist skinhead cruising down Hawthorne Street on Portland’s east side; the Neo-Nazi stopped his car, emerged with a group of friends brandishing bats, and gave chase. The anti-racists fled to a nearby house, where they gained entry from an elderly woman who agreed to shelter them. The racists trashed the woman’s house and car that night. The story found its way to the papers, and Treloar phoned the woman, asking if she would like some help defending herself. Terrified, she accepted CHD’s offer, and the group posted armed security on the elderly woman’s porch until she felt safe enough to let them go. When the newspapers spread the story to the public, the CHD found generalized support for their stance against racism.

A similar episode came about when a national racist skinhead group new to Portland at the time called Volksfront began to harass the community. One immigrant in particular received a gross amount of threats, and their family asked the CHD to come defend their home just in case. CHD members arrived at their humble trailer, and stayed for some time on the floor of their living room until the family agreed that the threats had ceased.

“There were several situations where our people who had concealed weapons were confronted by groups of boneheads and either pulled the weapon or made it clear that they were armed and the boneheads backed off,” Treloar told me. “There is no doubt in my mind that in several instances they would have been attacked, since we had people who were taking down car license plate numbers, staking out houses or infiltrating gatherings.”

These encounters did not always end peacefully, requiring tenacious legal and media strategies. In one altercation between a neo-fascist skinhead and anti-racists, shots fired led to the death of fascist skinhead Erik Banks from the band, Bound for Glory.* The CHD mobilized to form a media defense position, which helped generate positive public opinion, contributed to a positive plea bargain deal. “Now there were other attacks against Nazis, some of which were more difficult to defend. They were understandable but perhaps not as well thought out that earned people some shorter jail time,” Treloar explained. “What’s notable is again the people who attacked the boneheads after a certain point did very little time, and were generally hailed as heroes in the community we were trying to create [relationships in] at the time.”

A few years later, Volksfront attempted to organize a music festival in Portland, and a group of anti-racists organized into a new organization to confront the challenge of an insurgency. Calling itself Rose City Antifa (RCA), this group used intelligence to discover the prospective venues of the event, and contact them to shut down the show. Although Volksfront would host their event eventually, it took place in secret, in a small venue, and few people came. RCA gathered information on key Volksfront members, outing them to their places of business and in their communities. After a while of this kind of information dissemination, as well as anti-racist skinheads on the street, Portland’s Volksfront chapter disintegrated. RCA continued, attending gun shows to detract from the Oregonians for Immigration Reform and the American Freedom Party, a white supremacist organization derived from neo-fascist skinhead group in California, which involved extensive planning for security.

Despite their success, RCA noted that the movement was not without problems. A female member of RCA explained, “one of the major issues of being a woman in the antifascist scene is constant issues with sexism. All of the major falling outs have been around that issue.”[15] RCA also reminded me of the strife within the antifascist community between the well-endowed non-profit groups like the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) and the smaller Antifa groups. So while both militant antifascist and non-profit legal groups fight for the same causes, the class, race, gender, and strategic differences cause friction within the broader community.

Perhaps the most important lesson from the last forty years of antifascist and anti-Klan organizing in the US is that opposition movements cannot function without simultaneously building communities. By undermining fascist groups’ ability to organize and disseminate through prolonged and committed antifascist campaigns, the left will be able to shift the narrative of the rise of the far right toward the mobilization of strong, organized power through mutual aid and solidarity.[16] In the words of Southern Civil Rights organizer Alfred “Skip” Robinson, “I don’t want to be known as an Anti-Klan fighter. I want to be known as someone who fights for our people’s needs. When we fight for the people’s needs and the Klan messes with us, then we deal with them. If you want to bring death to the Klan don’t talk about it. If you want to bring death to the Klan then organize and bring death to the Klan.”[17]

* Correction, 12/25/2016: Previous person listed in this essay as having been killed was wrong, and was actually the person that served four years for manslaughter and was an anti-fascist.

- [1] Quoted in Amilcar Cabral/Paul Robeson Collective, Greensboro Collective, The Greensboro Massacre: Critical Lessons for the 1980’s (Raleigh, NC: Amilcar Cabral/Paul Robeson Collective, 1980).

- [2] Elizabeth Wheaton, Codename Greenkil: The 1979 Greensboro Killings (Athens: University of Georgia, 2009), 116.

- [3] Quoted in Amilcar Cabral/Paul Robeson Collective, Greensboro Collective.

- [4] Ibid.

- [5] “Editorial,” Death to the Klan: Newsletter of the John Brown Anti-Klan Committee, November, 1979, 5.

- [6] “Chicago: Confronting the Racist Right,” Breakthrough, Vol. XI, No. 1, Winter/Spring 1987, 9.

- [7] Interview with M. Treloar, November 15, 2015.

- [8] Breakthrough, 12.

- [9] Interview with Kieran Knutson, August 6, 2015

- [10] Interview with Mic Crenshaw, August 31, 2015

- [11] Toronto ARA co-founder Big B, Interview with author, November 12, 2015.

- [12] “Anti-Fascism in Toronto” and “Interview with a Member of Anti-Racist Action,” Arm the Spirit, No. 16, Fall 1993, 3-11

- [13] Elinor Langer, A Hundred Little Hitlers (NYC: Picador, 2003).

- [14] Interview with M. Treloar, November 15, 2015.

- [15] Interview with RCA.

- [16] I am using “power” here in the sense that scott crow uses it. See scott crow and transition bus, “Dual Power Transitions in Austin, Texas,” scottcrow.org, retrieved July 6, 2016.

- [17] Alfred Robinson was a leader the United League of Mississippi, which advocated community self-defense as well as civil rights and local electoral campaigning. In 1974, Robinson and a woman running for county commissioner were ambushed and fired upon by the Klan. When Robinson returned fire, the Klan scattered, and the United League members were able to apprehend Klansmen, one of whom was revealed to be the son of a local elected official. (See Dr. Akinyele Umoja, “He Was Not Afraid: Dr. Akinyele Umoja On Alfred ‘Skip’ Robinson,” Youtube.com, January 13, 2012.)