Filed under: Development, Editorials, Environment, Indigenous, Midwest

I went to the Standing Rock event at the Four Freedoms monument last Sunday. I have been inspired by the North Dakota protest because it was initiated by the local people (Dakota Indians) and because of the protest’s diversity of tactics–from imaginative non-violent blockades, law suits, and public speaking tours to land occupation, property destruction, and the public declaration that this fight is to the death. I am further compelled by how this fight, to stop an oil pipeline from being constructed through a river, being fought on Native land intersects with all of the different grounds on which the genocide of native people has been waged–state bureaucracy, environmental destruction, incarceration, economics, gender, and race to name a few. The Standing Rock encampment has swollen to over ten thousand people because the Dakota have not only waged this fight in the largest indigenous cross-national alliance in history, but welcomed everyone from anywhere in recognition that we all suffer from these same indignities.

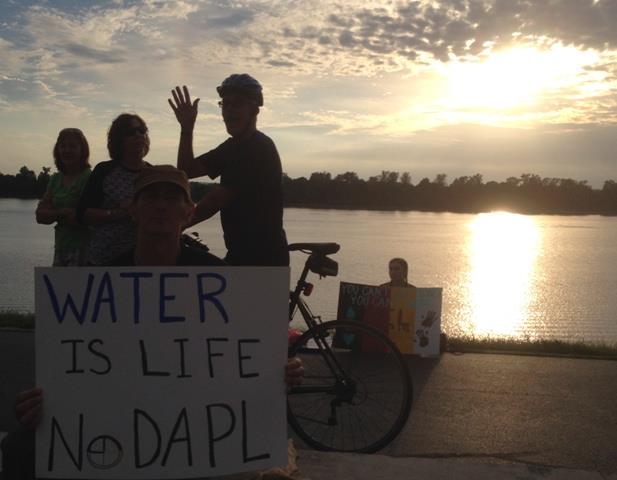

I learned over the years that social issues are just that, social; they tend to affect as many people as possible. This realization can feel overwhelming but I’ve learned too that it means each of us can do something about them. Upon seeing a promotion for the local event, I put up a poster printed for solidarity actions in Bloomington. I covered over the time and locations for the Bloomington events, and wrote in those for Evansville, leaving visible the text tying Standing Rock to the Sept. 9th Prison Strike, a strike that is ongoing and has made unimaginable cross racial advancements in one of the most segregated and racialized spaces. Though, to my knowledge the local event organizers hadn’t connected the two historic movements. I thought it especially appropriate considering Native Americans have the highest rate of incarceration in the U.S. At the event the organizers had attempted to facilitate something for everyone to do from making signs to collecting donations of clothes and food and an array of supplies to send up to Dakota, as well as listening to Indigenous presenters. All if this next to the Ohio River, running along polluted below us as if underlining the similarities in our shared conditions.

The Dakota peoples’ embrace of broad based support both tactically and as multi-issued, seems as though it should help alleviate the tendency of white people to appropriate minority struggles. Upon first getting to the event location I had sat down next to what seemed like two young white women; one of them began to tell the other how her mom said that she had some “Cherokee blood in her family.” I changed seats. Overall people seemed respectful during the event. Non-indigenous presenters began any traditional activity by first announcing that they had requested and received permission to perform the act. I took this as an effort to not steal culture and continue dispossession, a small step toward admittance for what “white culture” actually is and some responsibility for it. I was moved to tears to hear the indigenous presenter from the Long Plains Nation speak in his native language. It is common genocidal practice for colonial powers to outlaw the indigenous tongues of those they settle. I think this was only the second time in my four decades of life that I’ve heard a Native American language spoken in person.

My first and only other instance of hearing a native speaker was when I had the honor of being party to a conversation with a member of the Shawnee tribe. Comrades in Carbondale had arranged a meeting with a former AIM member who was teaching Shawnee traditions and protecting tribal land in Southern Illinois, not far from an anti-authoritarian land project where I’ve been putting my efforts. The conversation was about giving back use and/or ownership of land to the tribe. Though there was no decision at that meeting, it began to answer the question of what we might have in common. The conversation elaborated an image of the future that included all those present, young, old, queer, straight, men, women, Native and non-Native. We each had a voice and a distinct story to intertwine with the others. We simply didn’t finish telling our stories that day. We certainly didn’t finish intertwining them.

I’ve seen these bonds strengthen as the threads of these questions multiply and interweave, supporting dozens of people and bringing them together from all across this country. In the North Georgia mountains, anarchists have spent over a decade fostering a relationship with a Cherokee comrade who will spend the majority of his life apart from them, in prison. Oso Blanco is in prison for robbing over twenty banks and giving a significant portion of the money as reparations to the indigenous fight of the Zapatistas. However the land project provides him with direct relation to empowering the practice of his Cherokee ways of life. In a recent letter to Evansville Letters to Prisoners, Oso wrote about the vigor and inspiration that he feels in his cell when receiving information about the Standing Rock actions. In reading his letter, I feel a sense of hope when single issues are sown together in a manner that they loop back through a larger tapestry, becoming tighter, stronger, and more resistant to being torn apart.

At the solidarity event on Sunday, Matthew Black-Eagle Man Cordes made the distinction that the folks at Standing Rock aren’t protesting, but that they are protecting. They are protecting a way of life and of being. “Water is life” is a hashtag online to draw attention to Standing Rock, and it was on multiple signs at the down town event. I often harbor a cynicism when holding signs at protests, when “speaking truth to power,” because I don’t believe “the powerful” care to listen. In the voice of Black-Eagle Man those gathered heard a desire to take back power. He closed his presentation with a story about the state charging him with two felonies for practicing his traditions, and then asserted that the contamination of the waterways by an oil spill would mean a further advancement of the U.S. war against his people (now at less than 2% of U.S. population).

Genocide is a practice, at times a quick and sloppy carnage and at other times, like this last century, it is a slow, methodical, legal, impoverishment of everyday life. Finally it removes a people from history, it disappears them. They cease to even be. This is the fight we need to take up together. This is our fight to be. To be Indian, queer, black, women, etc. is a daily and persistent fight for self determination; it is in Dakota but no more so than Evansville. We need water to live but we need each other to fight to be ourselves.

Much of what is at issue is the idea of borders, and the sovereignty of the Dakota nation, but also the borders around private property, the borders segregating races, the borders dividing gender. At issue is the possible and literal poisoning of a river, but what has presented itself as an alternative full of possibility is the free and fluid movement of people coming together. Our fight to be is where we are, even when our fight is the need to be somewhere else. Many of the early colonies were populated by people brought here to work off debts to attain “freedom” supposedly in its entirety. It wasn’t uncommon then for folks to abandon those debts and go live with the natives. Freedom in its entirety isn’t just freedom from polluted waters, but freedom from debt, freedom from segregation, freedom from slave/wage-labor, freedom of choice, etc. Water is life, yes, but all of this is our lives. As the popular imagination has shifted farther right with the racist rhetoric of the presidential campaign blasted all over mainstream media, fascists have been busy at “reclaiming America” for their false identities of “white” “Americans”. The hysteria to build a wall between Mexico, to increase deportation, to privilege property and profit, to tighten already constricted gender roles, is a return in the direction of the oppressions from which people fled. We construct these borders every moment when we reinforce stereotypes, but we can deconstruct them by challenging our assumptions–by coming together with people who are different than us and allowing them to be a challenge to our assumptions and be accomplices in reclaiming our right to freedom in its entirety.

The largest assemblies I’ve been to in Evansville have been in response to corporate and state oppression, with the exception of the Fall Festival. But resistance need not be only somber or angry procession and protest but can be festive and a carnival of another kind. With the singing and display at the river Sunday there was a bit of all of it, but imagine what we could do with a bit more. A journalist from Yes Magazine was invited by her Native friend to come to Standing Rock and participate. I quote at length here the impression and effect of thousands of people building a community and a fight that maintains and celebrates itself:

That sense of purpose pervades the camp. While some plan the next direct action or post on social media, others split wood for fires, sort the river of donations flowing unabated into the camp, or cook for thousands of people in makeshift camp kitchens… hundreds line up for dinner. No money changes hands. Life at the water protectors’ encampment is much like life was for millions of years of human evolution–close to the earth, near a river, clustered in family and community camps.

Here, with a purpose that threads through generations, work, celebration, and activism are a seamless whole. Young people ride through the camp on horseback among tents and teepees. Are they providing security, learning traditional animal caretaking, or just having fun together? Elders tell stories of Wounded Knee, say prayers, and sing. Are they educating the next generation, building coherence, or guiding the actions? These things are not separate. They are all of a piece, all about rebuilding indigenous ways of life and standing against further destruction.

This is how we should be living, one person at our camp says. We give what we have to give, and take what we need.

Protecting the water and sacred sites brought people here. But the experience of being here is changing lives.