Filed under: Anarchist Movement, Featured, History, Mexico

A short history in commemoration of the life and times of Mexican anarchist, Librado Rivera, 91 years since his death.

Communism must be free like love; that is to say, it must be anarchist, or not exist at all

– Librado Rivera

Ninety-one years ago, today, March 1, 1932, Mexican anarchist Librado Rivera died in Mexico City. Rivera was a pivotal figure in the early 20th century transnational anarchist movement, whose revolutionary activities spanned from the Partido Liberal Mexicano and the anarchist newspaper, Regeneración, to post-revolutionary Mexico, the anarchist group, Los Hermanos Rojos, and the anarchist newspapers Sagitario, ¡Avante!, and ¡Paso!. Outside of small groups of anarchists and historians, the majority located in Mexico, Librado Rivera has been mostly forgotten.

Born in 1864 in San Luis Potosí, Mexico, Rivera studied at the normal teacher training school in the state capital, later becoming a teacher of history and geography. In 1900, Rivera joined the Ponciano Arriaga liberal group in San Luis Potosí, one of many liberal groups forming across Mexico at the time who were opposed to the Porfirio Díaz dictatorship. Rivera served as delegate for the Ponciano Arriaga group at the first national liberal congress in San Luis Potosí in 1901. There he met Ricardo Flores Magón. The two became lifelong comrades.

Due to his participation in the liberal groups, and their radicalizing critique of the Porfirio Díaz government, Librado Rivera was jailed twice, first in San Luis Potosí, and again in Mexico City, the second time alongside Ricardo and Enrique Flores Magón. It was during this epoch that Rivera was given the nickname, Fakir, for his fortitude and capacity for concentration within the hostile and debilitating prison environment. Unlike the Muslim Fakir who renounces material comfort dedicating himself to god, Rivera would renounce material comfort dedicating himself to the cause of the poor, marginalized, exploited, and oppressed.

In 1905, in consequence of the arrests and heightened repression, Rivera traveled to the United States, reuniting in exile with Ricardo and Enrique Flores Magón in St. Louis, Missouri. There, they formed the Organizing Council of the Partido Liberal Mexicano and re-initiated the printing of the newspaper, Regeneración. It was also in St. Louis, Missouri, where they would first come into contact with other immigrant socialists and anarchists, including Emma Goldman and the Spanish anarchist Florencio Basora.

After the arrest and ongoing persecution of different members of the Organizing Council of the Partido Liberal Mexicano, including Librado Rivera, they relocated to Los Angeles, California, reuniting there in June of 1907. Rivera made the trip west over a six-month period, staying in Denver, Colorado Springs, El Paso, among other cities along the way. Once reunited in Los Angeles, the Organizing Council of the Partido Liberal Mexicano once again took up their editorial work with Regeneración.

While the Partido Liberal Mexicano had originally organized around liberal politics, it was around this time that they turned to anarchism, most likely as a consequence of the years of state repression, along with influence from immigrant anarchists and socialists who they came into contact with in the United States. In a letter from LA County Jail, on June 13, 1908, Ricardo Flores Magón would write:

…we’ll continue calling ourselves liberals in the course of the revolution, but in reality, we’ll go on propagating anarchy and carrying out anarchist acts. We’ll continue expropriating from the bourgeoisie and making restitution to the people with what we seize.

It was indeed anarchist politics that would animate the Organizing Council of the Partido Liberal Mexicano going forward, building alliances and relationships with the likes of Emma Goldman, Alexander Berkman, William C. Owen, Voltairine de Cleyre, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), and others. Librado Rivera, and the rest of the Organizing Council, would spend the next ten years in and out of United States prisons and jails, publishing Regeneración, coordinating armed revolutionary activity in different parts of Mexico, and serving as a fundamental node in the international anarchist movement.

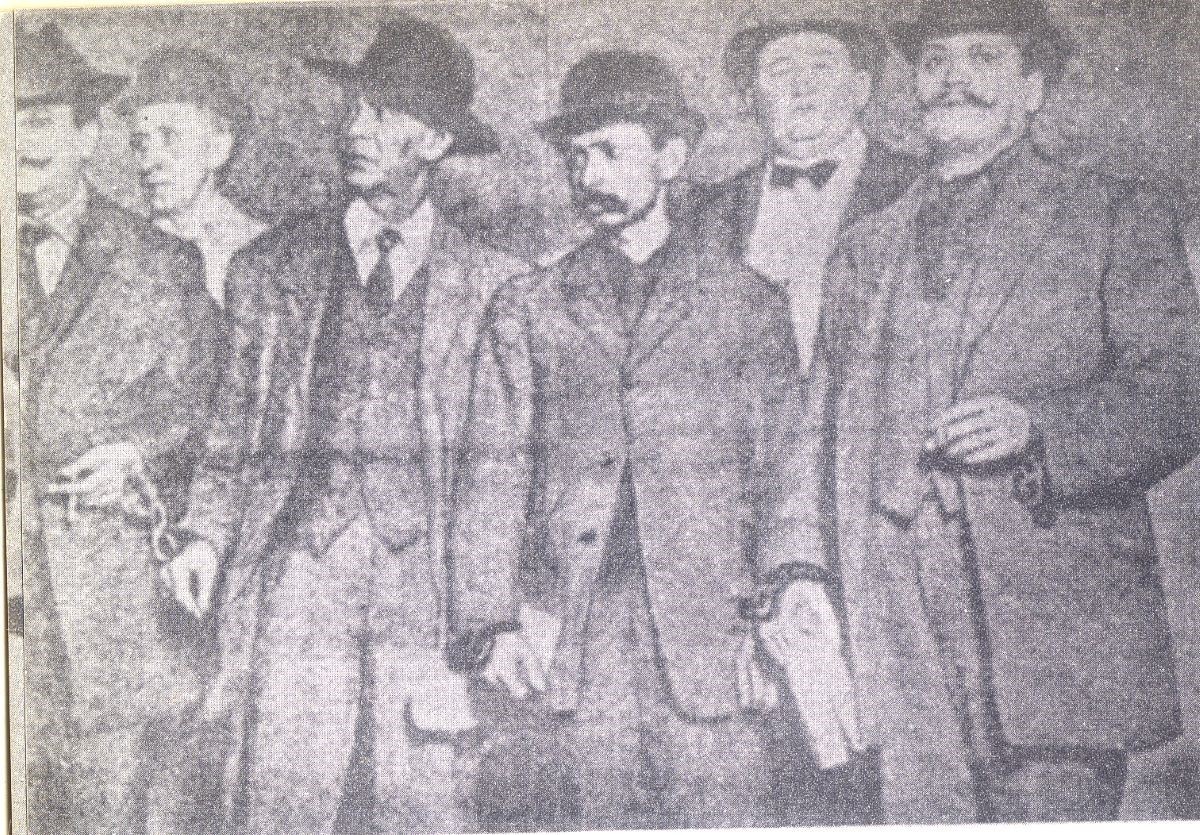

In the front from left to right: Ricardo Flores Magón, Anselmo L. Figueroa, Librado Rivera, and Enrique Flores Magón in 1912 being led by two policemen (in the back) to the train station in Los Angeles, California, to be transferred to the prison on McNeil Island, Washington.

In 1918, Rivera was detained in Los Angeles, California, alongside Ricardo Flores Magón, and accused of breaking the neutrality laws of the United States. Their crime was having published in the March 16, 1918 edition of Regeneración, “The Manifesto to the Entire World and to the Workers in General.” The manifesto was signed solely by Ricardo Flores Magón and Librado Rivera. It read in part:

Let every man and woman who loves freedom and the anarchist ideal, propagate it with determination, with tenacity, without concern for mockery, without measuring the danger, without regard to consequences; let’s get to work comrades, and the future will be our anarchist ideal.

On this occasion, Rivera was sentenced to fifteen years and Ricardo Flores Magón to twenty. After a short time in prison on McNeil Island, in December of 1919, Ricardo Flores Magón was transferred to Leavenworth, Kansas, extremely ill, seeking a different doctor and relief from the cold and wet climate on McNeil Island. Librado Rivera was transferred to Leavenworth nine months afterwards in 1920.

There in Leavenworth, Ricardo Flores Magón would die on September 21, 1922. Rivera later wrote of his final interaction with Ricardo Flores Magón inside the Leavenworth Penitentiary:

The evening of the 20th was the last time that we saw each other in the food lines. It was also the last words that Ricardo and I spoke to one another; words that I hold in my memory as an eternal farewell to the dear compañero and brother. Together for 22 years, we lived through constant persecution, death threats, and imprisonment from the henchmen of capitalism. That great rebel against all tyranny spent no less than thirteen years in the dungeons of Mexico and the United States of North America. Of the 20 years Ricardo remained in that country, a great part of that time he spent in chains in the dark North American dungeons.

Rivera was fundamental in getting the news of Ricardo Flores Magón’s death out to the international anarchist press, along with breaking the prison authorities’ narrative that Ricardo Flores Magón had died of heart disease. While Rivera couldn’t confirm the fact, he speculated that prison authorities might have had a direct hand in Magón’s death. That because when Rivera saw Magón’s body the morning after he died, his face and neck were bruised and black. Regardless of the exact circumstances, there is no doubt that Ricardo Flores Magón was killed by the state.

Following Ricardo Flores Magón’s death, and as a consequence of widespread solidarity efforts from different parts of the globe, Rivera was released from prison in October of 1923 and deported to Mexico. He was 59 years old. The US Justice Department had offered him a pardon if he were to commit to following US law. He refused. He was taken to the border in handcuffs, and released into Mexico. Of his 18 years of exile in the United States, 11.5 of those he spent imprisoned.

After a short period in San Luis Potosí living with his elderly mother, Rivera moved to Villia Cecilia, now Ciudad Madero, Tampico, a bastion of anarchist and anarcho-syndicalist activity at the time. There he participated with the anarchist group, Los Hermanos Rojos, becoming the informal director of their anarchist journal, Sagitario, from 1924 to 1927.

Rivera was a frequent contributor to Sagitario, denouncing the Mexican government’s war against the Indigenous Yaquis, covering the Sacco and Vanzetti case (even printing correspondence he maintained with Vanzetti), demanding the release of militants of the Partido Liberal Mexicano who were still imprisoned in Texas (known as the Texas martyrs), critiquing the authoritarianism of the Russian revolution, covering the issue of Mexican workers’ migration to the United States, among other topics.

Furthermore, Rivera filled the pages of Sagitario with scathing critiques of the post-revolutionary governments of Mexico, which would again land him in prison. On April 1, 1927, Rivera was arrested for authoring two articles published in Sagitario, denouncing the war of extermination being carried out against the Yaqui tribe in Sonora, and calling President Calles an assassin. For this, Librado Rivera spent seven months in the infamous Andonegui prison in Tampico.

Rivera’s imprisonment didn’t silence him. He continued writing, denouncing the repression against him, and doubling down on his criticism of the post-revolutionary Mexican governments. He turned to other anarchist newspapers, including Cultura Proletaria in New York and La Antorcha in Buenos Aires, to get his word out. In a letter written from prison and published in La Antorcha on October 16, 1927, Rivera wrote:

The Calles-Obregón government that appears discursively to be resisting Yankee capitalism, is in practice a true lackey, who even lends itself to modify and impose the laws that those millionaires crave, as do the politicians and millionaires of Mexico.

Rivera’s imprisonment would mark the end of the anarchist newspaper, Sagitario. During his detention, the offices of the newspaper were raided and the printing press burned.

Upon leaving prison in November of 1927, Rivera relocated to the northern city of Monterrey, starting the anarchist journal, ¡Avante! However, after just three issues, Rivera returned to Villa Cecilia due to mounting repression against him and against ¡Avante! in Monterrey. In Villa Cecilia, Rivera resumed his editorial work with ¡Avante! maintaining the publication until 1930.

Librado Rivera contributed to the pages of ¡Avante! with different topics from reflections on the Haymarket Martyrs in Chicago and the struggle for the freedom of Simon Radowitsky in Argentina, to anarchist critiques of authority, government, and elections.

Rivera’s criticism of Mexico’s political class didn’t subside either. He was arrested again, but only held for a few hours, for an article published in ¡Avante! on August 1, 1928, where he insulted Álvaro Obregón following his death. He wrote:

Congratulations to the humanity of the oppressed: a tyrant has died. We don’t want to know the details of his death. We do not need to know. It means the same to us if he was struck by lightning. The assassin of the Yaqui people is well and truly dead.

Librado Rivera was arrested four more times over the next couple years, with the offices of ¡Avante! ransacked and emptied of belongings. His last arrest took place on February 13, 1930. Shortly thereafter, on March 1, 1930, he was transferred by train to prison in Mexico City. He was released later that month, taking up residence in Mexico City with the anarchist agitator, Nicolas T. Bernal.

There in Mexico City, Librado Rivera would launch his last attack against capital and state, founding the monthly anarchist journal, ¡Paso!, in 1931. Librado Rivera wrote various articles in ¡Paso!, reflecting on his past comrades from the Partido Liberal Mexicano, including Ricardo Flores Magón and Práxedis Guerrero, and commenting on ongoing struggles taking place in Mexico at the time.

In February of 1932, Librado Rivera was run over by a vehicle on San Angel Avenue in the south of Mexico City. In the hospital, Rivera contracted a tetanus infection, dying on March 1, 1932, at 68 years of age.

Rivera lived an uncompromising life, committed to the cause of the poor and dispossessed, to the anarchist struggle against state and capital. Rivera was a crucial figure in the international anarchist movement both as a journalist and organizer, helping coordinate revolutionary action and solidarity across the US-Mexico border, across the Americas, and across the world. Rivera’s anarchism found expression in international prisoner support, anti-imperialism, Indigenous solidarity, critiques of post-revolutionary “progressive” governments. He was Fakir, a committed and focused revolutionary, doing the necessary work without interest in fame or fortune.

On the second anniversary of his death, in 1934, the Mexico City based anarchist newspaper, Voluntad, published an article in memory of Librado Rivera. There they wrote,

The first of March will mark two years since the death of a life committed to the defense of the libertarian ideal: Librado Rivera. By dedicating these lines to him on the second anniversary of his death, we do not seek to glorify his memory with the mystic fervor of believers. Nothing is further from our intention and nothing is more opposed to the belief of our deceased brother. However, we want to evoke the memory of the departed compañero, making a call to all anarchists to continue the work that Librado Rivera would defend with such enthusiasm.

Ninety-one years since his death, let this short history of Librado Rivera serve that same purpose: celebrating his memory, while making a call to carry on the anarchist struggle to which he dedicated his life.

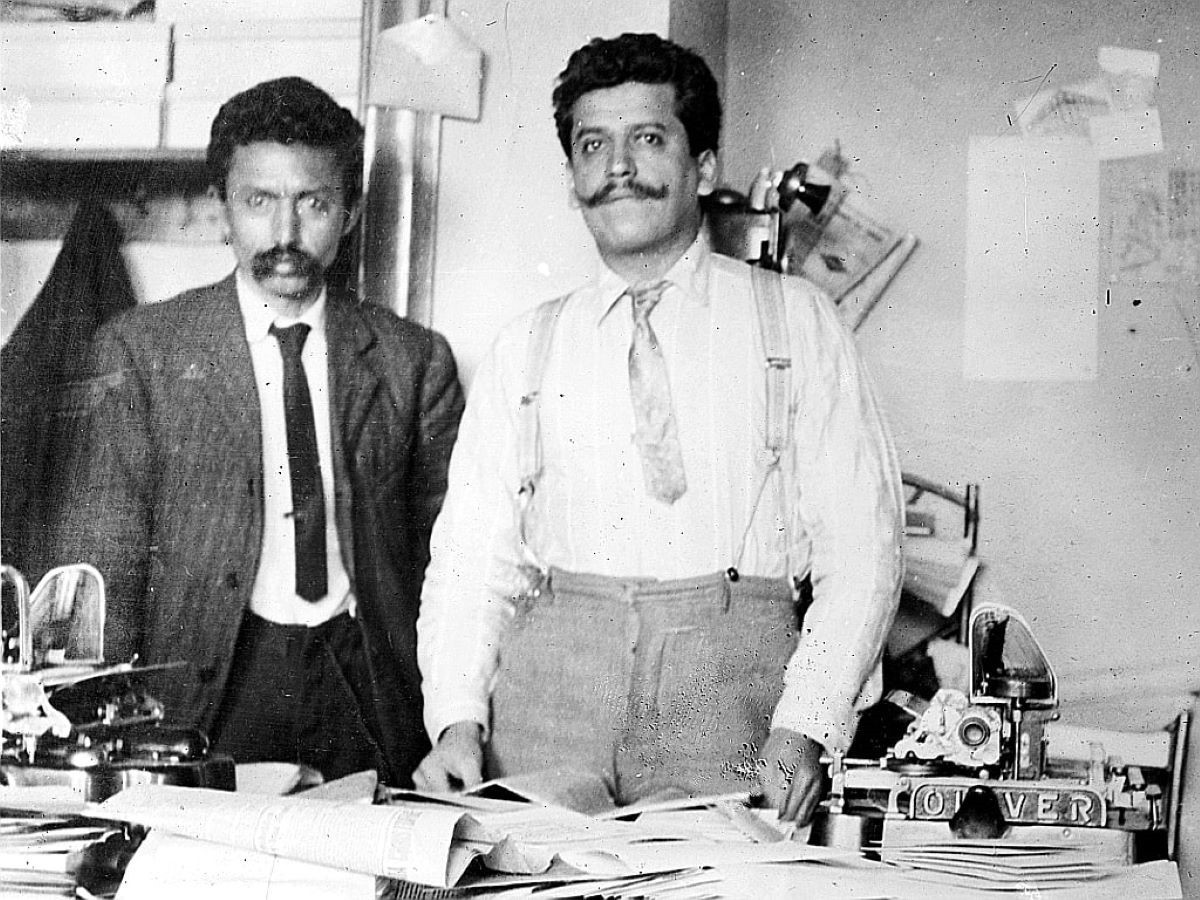

Cover Image: Librado Rivera (left) and Enrique Flores Magón (right) likely in the offices of Regeneración.