Filed under: Editorials, Environment, Indigenous, Insumisión, Land, Mexico, Repression

Originally posted to It’s Going Down

By Scott Campbell

Several victories for social movements in Mexico were recounted in the Insumisión posted on March 17. This edition focuses on the state’s response, which in the first part of April has been expressed through two of the state’s inherent qualities: force and coercion.

One of the victories mentioned was that of the Otomí community of San Francisco Xochicuautla in the State of Mexico. After years of organizing, in February a court suspended the expropriation decree issued by the federal government for a highway to be built through their forest and town. The community celebrated, but in a case of foreshadowing, said they would not rest until the entire highway project was canceled. The state emphatically made clear that the project was still on, when on April 11th it besieged and invaded the town with 800 to 1,000 riot police. In complete disregard for the court ruling, the police escorted in heavy machinery belonging to Grupo Higa (the owner of which is a close friend of Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto), that began clearing land for the highway and also demolished the home of one of the movement’s leaders. The solidarity extended to Xochicuautla was powerful and immediate, which included the Zapatistas and the National Indigenous Congress issuing a “Maximum Alert” both for Xochicuautla and Ostula in Michoacán, due to an ambush against the Community Police of that autonomous Nahua community, which killed one. This seemed to catch the state off-guard, as on April 13 they ordered the construction be stopped and promised to pay for the damages. But they also said they would be leaving a number of state police nearby to guard the machinery in the meantime. In response, the community has organized 24-hour patrols in case of renewed construction, and the situation remains tense.

With all eyes on Xochicuautla, on the other side of the State of Mexico, the army invaded the community of Atenco on April 12, escorting in workers planning the construction of Mexico City’s new international airport. In 2002, Atenco and its People’s Front in Defense of the Land (FPDT) successfully defeated a previous effort to build an airport on their lands. In 2006, they sustained an exceptionally brutal attack by the forces of Peña Nieto, who was governor at the time. Twelve of their members were imprisoned, with sentences of up to 112 years. Yet all gained their freedom in 2010 following relentless mobilizations. To take his revenge, in 2014, Peña Nieto resurrected the proposal to build an airport on Atenco’s lands. And just last month, as was mentioned in the last Insumisión, Peña Nieto’s handpicked successor, Eruviel Ávila, oversaw the passage of what has been called the Atenco Law or the Eruviel Law, allowing police to open fire on protests, guaranteeing their impunity, and punishing those who don’t. In response, dozens of organizations have formed The Fire of the Dignified Resistance to fight against the law, a mobilizing effort that contributed to the quick response to the attack on Xochicuautla.

On April 15, the National Coordinating Body of Education Workers (CNTE), a more radical faction inside of the National Union of Education Workers (SNTE), the largest union in Latin America, called for a national day of mobilization against the federal government’s plan to privatize and standardize public education. In San Cristóbal de las Casas, Chiapas, federal police brutally attacked the demonstration with tear gas and beatings, and on one occasion live ammunition, leading to running street battles with teachers throughout much of the day and all over the city. Similar repression also occurred in the state capital of Tuxtla Guitiérrez. Helicopters were used to fire tear gas at the teachers, and in one instance, the police fired tear gas inside of a hospital. The Fray Bartolomé Human Rights Center reported that at least 24 people were arrested, tortured and held incommunicado, with 18 teachers being flown across the country to a maximum security prison in Nayarit. Such fierce repression is likely a message being sent by the state as to what awaits CNTE teachers next month should they follow through on their announced plan for an indefinite strike beginning on May 15 that would impact 23 states.

As always, many other developments have unfolded in Chiapas. On April 3, Chol, Tzotzil, Tzeltal, and Zoque communities began a 200 kilometer march to demand justice for the November 13, 2006, Viejo Velasco massacre when four people were killed in a paramilitary attack designed to stoke tensions between Zapatista and non-Zapatista communities. Nine years later, those who carried out the attack have warrants out for their arrest, yet the state has not detained them. In San Isidro Los Laureles, an indigenous community that reclaimed 200 hectares of their ancestral land in December and who are adherents to the Zapatista’s Sixth Declaration, experienced helicopter flyovers on April 8, followed by an incursion of armed men into the community who fired seven shots before fleeing. Meanwhile, the autonomous Chol community of Ejido Tila was attacked twice last week, when 100 men, led by the local officials the people booted out of town on December 16, entered the community and on the second occasion fired four shots, seeking to create a confrontation in order to justify the use of state force to crush the autonomous project.

The sixty displaced members of Primero de Agosto denounced the intimidation and interference they are experiencing from the paramilitary group CIOAC-Histórica. This is the same group that displaced them more than a year ago and who also attacked the Zapatista community of La Realidad, destroying several buildings and killing compa Galeano in 2014. In some good news, the Tzotzil community of Los Llanos announced that back in January the courts ruled that the planned San Cristóbal-Palenque tourist highway could not be built through their lands. This ruling will hopefully lead to similar judgements for other indigenous communities resisting construction of the highway, such as Ejido Candelaria, though we’ve seen just how much the Mexican state respects its court rulings. Sixty Chol and Tzeltal communities from Guatemala and Chiapas announced their plans to oppose the construction of a binational dam on the Usumacinta River, the arbitrary border between Mexico and Guatemala. The group Women and the Sixth released the first edition of their new magazine, organized around the theme of “Patriarchy is Violence, Machismo Kills.” Dorset Chiapas Solidarity has a great roundup of Chiapas-related news from March. Keep an eye out for the April edition at the end of this month. Finally, a recent Oxfam report found that since the Zapatista rebellion in 1994, Chiapas has received the most funding of any state to combat poverty, yet still remains the poorest state in Mexico. Well, Governor Manuel Velasco has to pay for his wedding and propaganda somehow.

To the west in Guerrero, residents of several communities have blocked access to the Media Luna gold, silver and copper mine in Nuevo Balsas since March 30, protesting the contamination produced by the project owned by the Canadian company Torex Gold Resources. On April 1, 3,000 residents from 185 indigenous communities in the mountains of Guerrero blockaded roads leading into and out of the city of Tlapa de Comonfort. They were demanding the government actually implement the plan it developed after more than 4,000 homes were damaged in 2013 during Hurricanes Ingrid and Manuel. The Amuzgo community radio station in Suljaa’, Radio Ñomndaa – The Word of the Water – announced on April 3 that it was restarting transmissions after two years off the air. They write, “We want to say that we are staying alert to your struggles and resistances, this station, humble and simple, dignified and rebellious, also belongs to those who defend and care for their territory, to those who organize for the dignity of their peoples and communities, to those who decided to say enough with their contempt and to not allow them to continue trampling on us.” On April 10, ex-political prisoner Nestora Salgado launched the campaign “Putting a Face and a Name on Political Prisoners in Mexico,” urging people to mobilize to free the political prisoners in Mexico, in particular those arrested for carrying out their duties as community police in Guerrero.

A video surfaced on April 14 of two military police torturing a woman in Ajuchitlán in 2015, pointing weapons at her and repeatedly suffocating her with a plastic bag [trigger warning]. The Secretary of Defense says those involved have been detained and will be tried in military court. The likely result: see Tlatlaya below. Such brutality is not an isolated incident, which is why residents of Atoyac and Tecpan blockaded a federal highway on April 4 demanding that the military leave their communities as they are tired of the constant abuse.

The case of the 43 disappeared students from Ayotzinapa, Guerrero is back in the news as the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (CIDH) announced on April 15 that it was withdrawing the Interdisciplinary Group of Independent Experts (GIEI) from the country. The GIEI was formed to investigate the disappearance of the students and their work is supported by the students’ families. In theory and on paper, the Mexican government agreed to the GIEI’s presence and pledged to cooperate with them. Yet they have consistently undercut the GIEI’s investigation, especially once the GIEI rejected as “scientifically impossible” the government’s “historical truth” that the students were killed and then burned in a dumpster. Since that time, the government has largely ceased to coordinate with the GIEI, has released statements intentionally undermining the GIEI’s work, and issued claims that the head of the GIEI had embezzled two million dollars. In response, the current students at Ayotzinapa have started an open-ended strike to demand the GIEI stay, and on April 15, the students’ relatives outwitted the federal police to begin a 43-hour encampment in front of the Interior Ministry in Mexico City, chaining themselves to the building’s fence.

Back in June of 2014, the Mexican army reported that it had killed 22 members of a kidnapping gang during a firefight in the rural municipality of Tlatlaya in the State of Mexico. An investigation later showed that at least 15 of those killed were civilians who were detained, tortured, interrogated and then executed. In a rare occurrence, seven soldiers faced charges related to the killings, though in a closed military court and with no officers indicted. It took a court case by a survivor of the massacre for the military court’s verdict to be made public. On March 30, it was revealed that six of the seven soldiers were found innocent with the seventh found guilty of disobedience and sentenced to one year.

A piece by BusinessWeek has created a bit of a stir in Mexico after it revealed, to few people’s surprise, that President Enrique Peña Nieto dropped $600,000 to hire Andrés Sepúlveda, a hacker from Colombia, to help him win the 2012 election. Sepúlveda “led a team of hackers that stole campaign strategies, manipulated social media to create false waves of enthusiasm and derision, and installed spyware in opposition offices, all to help Peña Nieto, a right-of-center candidate, eke out a victory.”

A recent article summarized some of the chilling tallies reflecting the reality of violence in Mexico under Peña Nieto. It notes that between 2012 and 2014 the number of girls under 18 who were disappeared rose by 191 percent. In Morelos, mass graves containing 150 remains were recently discovered. And the federal government acknowledged that in the search for the 43 disappeared students from Ayotzinapa, 60 mass graves have been found, with the remains of at least 129 people. The Disappeared Persons Search Brigade, a national group formed to locate disappeared people without the assistance of the state, found eleven gravesites in San Rafael Calería, Veracruz on April 15. Earlier this month, organizations commemorated five years since the discovery of a mass grave containing the bodies of 72 migrants from Central America in Tamaulipas on April 7, 2011. A total that rose to 265 remains following the uncovering of more graves. A report by Radio Zapatista documents the increased use of torture against migrants and Mexicans who “look” like migrants, in particular indigenous people, by National Migration Institute officials as a means to dissuade other migrants from attempting the journey.

There are several additional stories to mention from the past few weeks. Reyna Gómez Solorzano, an undocumented immigrant from Belize who has been living in Quintana Roo for the past thirty years, was sentenced to 25 years in prison on March 23. Eight months prior, Reyna defended herself with a knife against one of the frequent beatings from her husband. Upon wounding him, she immediately called an ambulance, but he ended up dying. The Network of Feminists of the Peninsula has been organizing demonstrations and legal support for Reyna. On April 5, Miguel Ángel Castillo Rojas, a member of the Veracruzan Popular Teachers Movement, was assassinated in his home by three masked men in Las Choapas. Also in Veracruz on April 5, fifteen Nahua women were arrested and dozens wounded when police in Orizaba attacked as they were selling their wares near a local market. The women fought back and support for them was quickly mobilized, leading to their release two days later. Vendors in Mexico City who operate in a space desired by capital for commercial development were attacked by 500 riot police, who beat them and destroyed their shops, leaving 120 families without a source of income. For four days in April a forest fire raged in Tepoztlán, Morelos. When the state did nothing but put helicopters with no fuel on a field for a photo op, the people organized themselves into brigades to put out the fire. Check out the video. Anarchists in Tijuana have announced the opening of a new social center in May. The Mauricio Morales Squatted Social Center has the intention to “agitate/build ideas and practices antagonistic to power and whatever form or expression of authority and domination.” Mauricio, aka Punky Mauri, was an anarchist in Chile who died on May 22, 2009, when an explosive meant for the Gendarmerie School went off in his backpack.

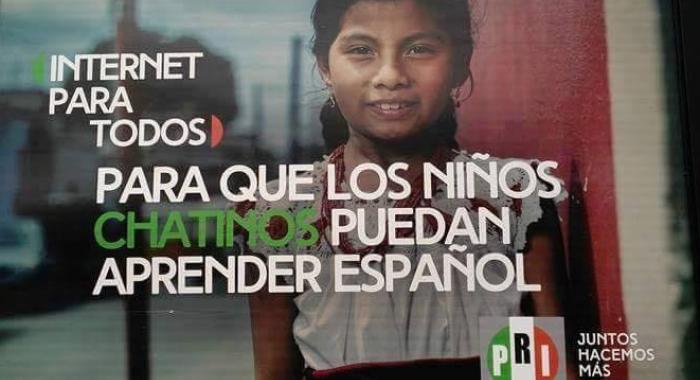

In Pachuca, the capital of Hidalgo, a police attack wounded tens of protesters and led to seven arrests. People came out on April 2 to oppose plans to shut down several combi routes (low-cost microbus transport) and replace them with commercial service operated by Tuzobus. Farther north, in Creel, Chihuahua, whose Copper Canyon is a popular tourist destination, the Tarahumara community started a blockade of the airport last week, shutting it down in protest of the destruction caused by its construction. Police used live ammunition, tear gas, Tasers, and rubber bullets against students blockading train tracks in Tiripetío, Michoacán. The students, from a nearby teachers’ college with a tradition of militant action that is often met with brutal repression, were demanding the payment of scholarships owed to them by the state. One hundred were wounded and ten were arrested. The Zapotec community of Álvaro Obregón in Oaxaca, who for years have resisted the imposition of multinational wind farms on their land, released a statement that they will not allow ballot boxes to enter their community for the July 5 state elections. In 2013, their community assembly decided to ban political parties, stating that “the number one enemy of our struggle are the political parties, be they the PRI, PAN, PRD or any other name.” Since this recent campaign ad discloses what the Oaxacan branch of the PRI thinks of indigenous people, such animosity is not surprising:

“Internet for all: So Chatino children can learn Spanish.”