Filed under: Anarchist Movement, Featured, IGD, Incarceration, Interviews, Mexico, Solidarity

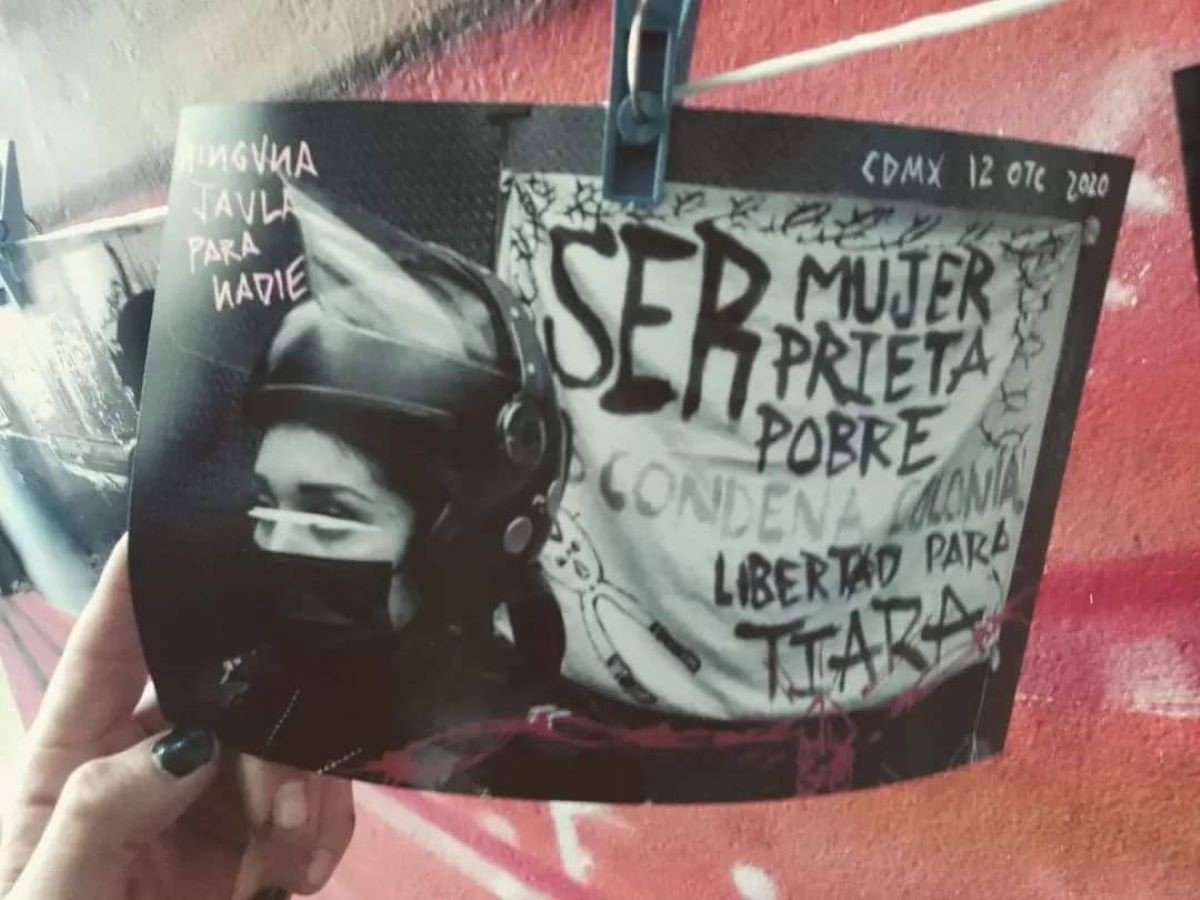

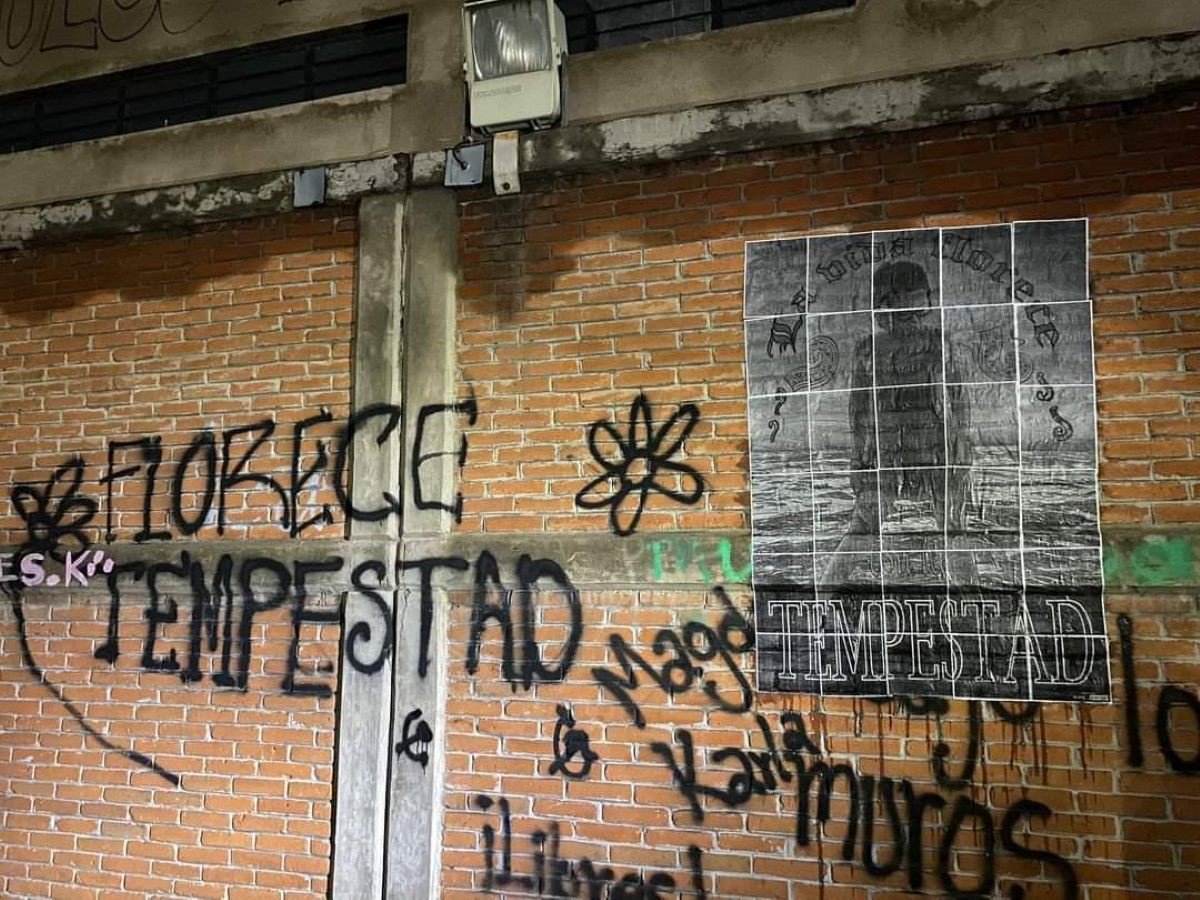

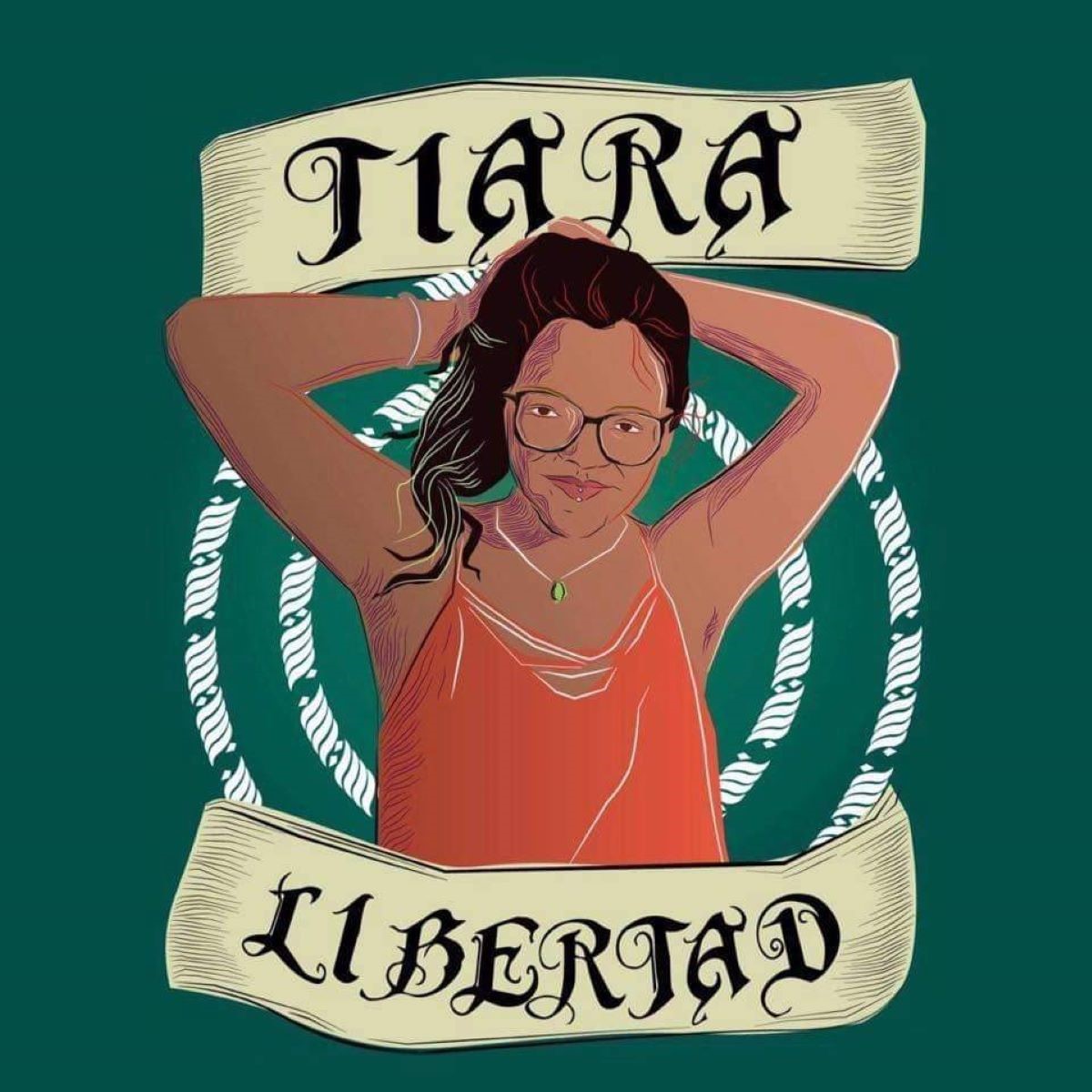

Interview with Mexican anarchist and ex-prisoner Tiara Tempestad on their experience doing almost four years in prison in Mexico City, a fanzine project they were involved with on the inside, prisoner solidarity and resistance to prisons. The interview in Spanish can be found here.

IGD: Can you start off by presenting yourself? Who are you, where are you from, in what were you up to before you were taken to prison?

It’s a pleasure to share my voice from physical freedom, to be able to greet folks face to face and be able to hug my friends. I am Tempestad, I currently live in Mexico City. Like everyone else, I had a life before I was detained, I had one inside prison, and now I am living life post-prison.

IGD: You were detained in August 2020 in Mexico City. Can you tell us about the first days and weeks in prison? What advice might you have for folks who face prison to survive their first days?

Being imprisoned is a shock. It’s like entering a world with entirely different dynamics. The first week in prison I was held incommunicado. They had me in isolation because of COVID. Afterwards they moved me to the dormitories.

I remember during the first few days, “Rondin” (a special security force) scolded me for staring out the window and onto the street. After a week, and three failed court hearings, I was hit with a “carcelazo;” a brutal anxiety crisis when I realized that I was not going to get out. I also had conflicts with compañeras for the way in which they were organizing the cell.

From the very beginning, the prison guards and some other women are determined to scare you into submission, to get money from you, or to make you look like a monster. Other compañeras try to uplift your spirit and comfort you, but they are just as broken as you are. Those early days are difficult. In addition, you have to deal with the legal situation. You are afraid of what is being said in hallways and by the lawyers. You enter into a state of uncertainty and vulnerability, you live on the edge.

It is important to be realistic and recognize that you are not going to get out the next day. At least in Mexico, legal processes last from at least three months to two years. It is difficult to put aside hope, but doing so reduces the uncertainty along with the possibility that you and your networks will be abused, economically and emotionally.

The body is on alert. It is a moment to examine the terrain: review the different networks of power and the implicit rules of coexistence, safe spaces, shelters, tricks. You can hold onto anything to maintain relatively firm: memories, beliefs, fictions, your loved ones, yourself.

It is a mental battle, losing your freedom is a type of pain. There isn’t a “correct” way or manual on how to react.

IGD: On July 1, 2024 you were released from prison after spending three years and ten months behind bars. What was day to day life like on the inside? What were you doing to stay busy and healthy? What were some of the worst and best moments?

The question of how you organize your life depends a lot on the area and the building you are in. The internal rules are really strict.

The “candado” (when they open and close the cell) was at 7:00am and 7:30pm. The rest of the time we spent inside the cell chatting, watching TV, reading, dancing, sometimes fighting, discussing, cleaning, washing clothes, there were also drugs, moments of tranquility and others of being fed up.

I was in Building A for a year. I was only allowed access to the patio for one hour a day and another hour for cleaning. There were 10-15 of us in the same cell for 23 hours straight. It was crazy. We usually slept during the day so it passed by more quickly, and at night we would do artistic things, weaving palm fibers and drawing. We managed to exercise, to eat, to get through the hours that seemed to last forever.

I spent the following two years in Building B. There the days were more structured with mandatory cultural, sporting, school, and work activities. I found refuge in theater and physical training, selling bleach and chicharrónes. I got to know more or less the routine, and I had more confidence than other compañeras. During that time, I began the fanzine project, Turquesa. We tried to eat well and generate money to pay for our expenses. The idea was to maintain active because sitting around and waiting was torture, the body was always in suspense between hope and desperation

The last few months I spent in general population which was practically the same but with a blue uniform. I continued selling chicharrónes and bleach, and I worked in the cafeteria. I focused heavily on Turquesa, training, sharing with the compas. There were collective money saving programs to combat the economic violence in the prison, and we learned to live in the moment.

My mother never left my side, she was always there during the visits. Some friends were allowed to visit as well, which helped me stay strong.

I remember my 24th birthday. We made hotdogs and broke out the weed. Twerking and cumbia filled the hallways, everyone was dancing. It was a lot of fun for a prison.

I also remember when a friend gave birth to her baby. They transferred her to Tepepan–another women’s prison here in Mexico City–to give birth. I was extremely anxious for her return and to see her with her new baby. It was such a joy to see the baby sleep so peacefully, knowing nothing of the prison bars or the laws.

The worst experiences I’d prefer not to remember. Sometimes I ask myself if they really happened.

IGD: You were in prison during the COVID-19 pandemic. How did the pandemic affect your life in prison?

It was like living in a prison inside a prison. The courts were closed, so a lot of the legal processes were held up. The courts only operated to imprison more people; the prisons were filled up.

The visits were reduced from four days a week to one day a week, from six people who could visit to just one family member. There was no fresh air, no mobility in the hallways, no physical contact with your loved ones.

Every week they “isolated” entire cells for possible contagion, but they didn’t attend to anyone’s health. They just separated them without a medical check-up. There were deaths, even though they said there were not. From then on, the prison authorities didn’t loosen the rules after the pandemic. The restrictions continued without any justification.

In 2023 around ten women began a hunger strike to regularize family visits, but nobody joined in. The strike was considered an “exaggerated act” among many of the inmates, and the prison authorities quickly pressured them into giving up their protest.

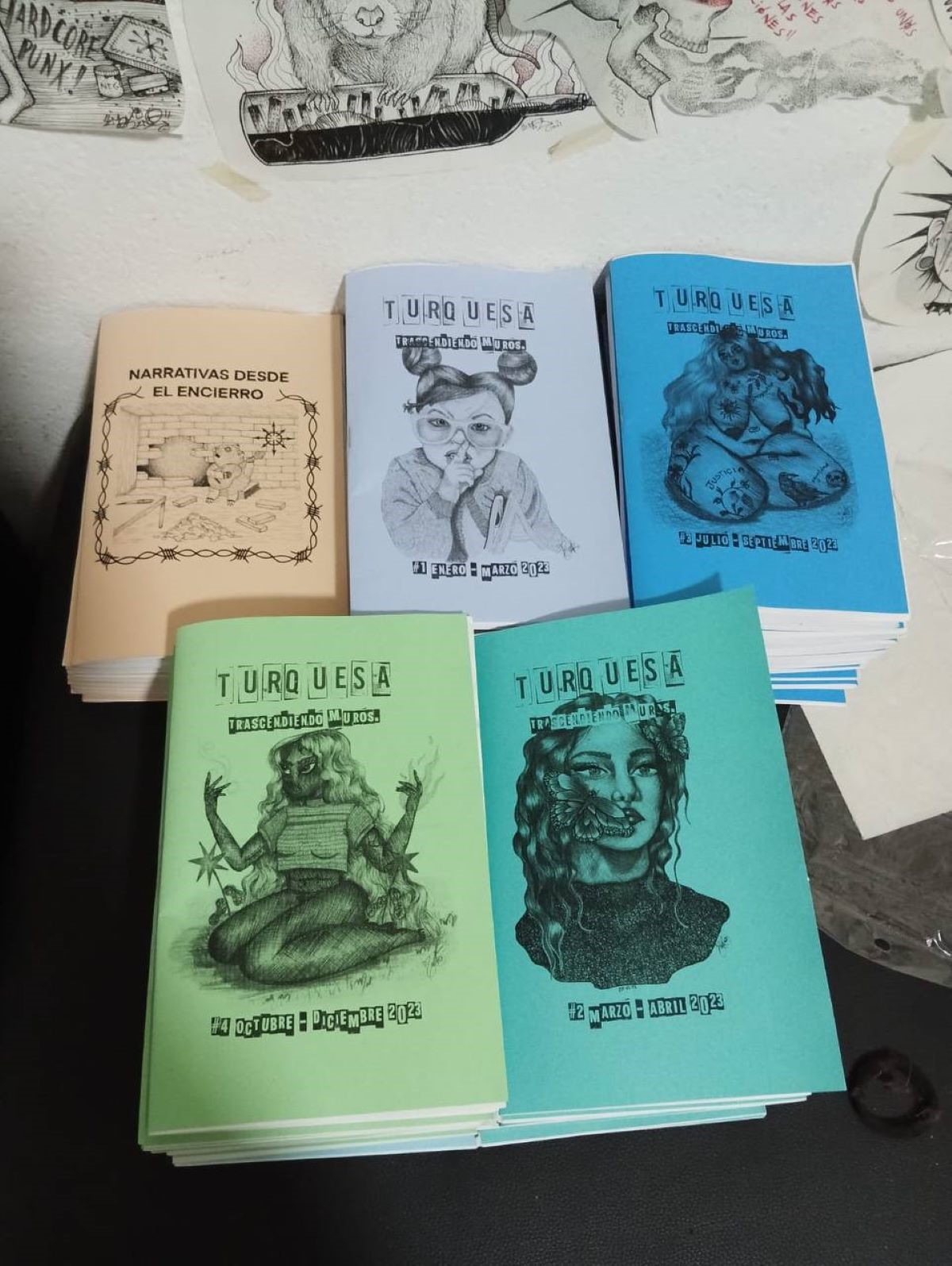

IGD: In prison you collaborated on a publication Turquesa: Trasciendo Muros. Can you tell us about this project? How did the idea come about? What was its production process like? What were some of the major challenges and gratifications of the project?

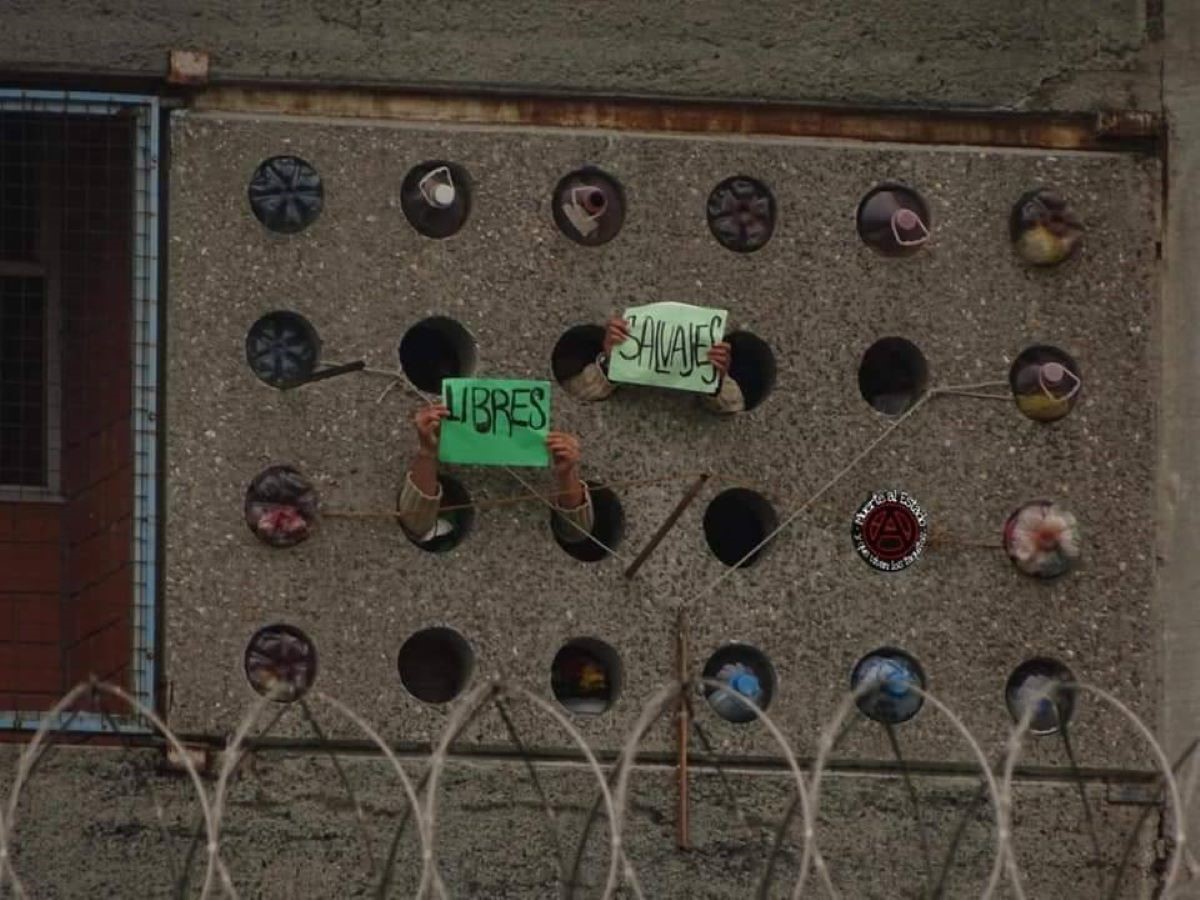

The idea came about during the first months between compas from different faraway places. I was sent fanzines from the outside and publications of ex-prisoners, like “El Canero,” along with other powerful texts from Spain, Chile, Argentina, and other places. We read enthusiastically because it was as if we had written them ourselves. We imagined everything that we could write and share from where we were located inside the prison of Santa Martha, and other prisons in Mexico City.

After a long process of “adaptation,” I signed up for a writing workshop that began in September 2021. In reality the workshop was an excuse to have a space for self-reflection and organization. There were those who wanted a “class,” but the majority of us went to get stuff off our chests, to talk shit about people and the prison, to read and write. Many writings and reflections came out of that time, but not all of them appear in Turquesa. We also developed comradery, certain unusual relationships, discussions, tears, laughs.

Turquesa was put together with the help of my mother who during every visit would bring copies and texts, or a USB drive which was prohibited. The compas of Micorriza edited and printed the zine on the outside.

One of the more powerful things was that nobody instructed us. Organizations regularly enter prison with “good intentions” and with the objective to “give voice” to prisoners, but they bring their own already formulated projects. Also, the secretary of the prison system encourages writing workshops but it uses the organization and work of the prisoners to justify their discourse of rehabilitation and treatment.

In Turquesa we wrote what we wanted without any third-party interference. There wasn’t any external funding or recognition, it was our personal expression. Eventually the reflections deepened, we went from telling each other how shitty the prison guards were using their first and last names, to criticizing the idea of the police; from sharing information about our legal cases to thinking about justice more generally in Mexico and beyond; from writing about the conditions in which we lived to giving a face and character to the people in prison.

It is not a strictly anti-prison publication. Each one of us had different opinions. We shared reality in that moment, but we had different opinions. There were conflicts, disagreements. We are not a collective or a stable group. Although we were four to six women who constantly wrote with the intention of demystifying state justice.

At one point we wanted to do interviews, but when the administration found out, they wanted to close down the workshop. There were occasions in which folks entered only to sabotage the space and make everyone uncomfortable.

The first time that the zine was printed and we got some copies into the prison, it felt really good. We all wanted a copy to share what we wrote. We also received letters from the outside, and that was crazy because many people think that we don’t read their letters, although indeed we do.

We have a draft of the fifth edition of the zine which we hope to be distributing at the beginning of March. A couple of the writings are still only on paper in prison in Santa Martha. The idea is to continue editing and printing the zine with less frequency, but to continue cultivating this mode of resistance and construction. We decided not to share it on social media, as some of the texts have names and the compas are still in prison with the boot on their neck for now.

If anybody wants to collaborate or share reflections, texts, poems, they can contact me directly on Instagram @tempestd13 or through micorriza on Instagram @la_micorriza, @Konspiracion_iconoclasta.

IGD: Beyond collaboration on the fanzine, what other types of collective organization, mutual aid, collectivity did you see in prison among the prisoners? What were the relationships like?

One survives in prison through sheer resistance, support, and organization mostly independent of the prison walls. In Santa Martha there aren’t autonomous organizations as there are in other contexts and in other countries. In Santa Martha organized crime is mostly in control.

But on the micro level there are indeed certain networks of solidarity that function. Organizing a cellblock means coming to an agreement on how food is distributed, what work requires more effort, who makes the decisions, on whose shoulder do you lean when you need to cry, how much money and power is given to the prison guards.

Evidently, the preferred and the most habitual form of management of life is based in hierarchy: the strongest person rules, money rules. Yet, there are times when that way of doing things isn’t sufficient, and acts of selfless mutual aid, solidarity, and empathy emerge.

For the visits, coordination and support are needed among the family members, who are usually mothers, grandmothers, aunts, and daughters.

Many times, the family members would befriend others in line waiting to enter the prison, and among them they would organize to get things in, to save their place in line, or buy supplies. In the end it was a network of favors that made the situation a little easier.

There are areas where mothers raise their children up to the ages of 4-6 years old. The raising of the children takes places collectively between the women, contrary to what many people think.

Prison is a hostile place and prone to suspicion, so the trust that was built between compañeras was not only important, but vital. The level of trust is what made the difference in order to survive.

For example, there was a considerable group of women from Colombia in the prison, who would organize between them to communicate with their families in Colombia. They would organize parties and other things, developing deeper bonds. Sometimes empathy derived from whether you were from the same neighborhood or colonia, let’s say Morelos, Tepito, Santa Cruz, Santo Domingo, etc.

I want to clarify that not all the support was mutual, nor was it all without self-interest. In the end, money and power were at stake.

IGD: You are an anarchist and you were involved in different social struggles before you were detained. How did your politics affect your time in prison? For you, what does it mean in practice to be an anarchist in prison?

On paper we learn many things but when you have to live them in your own flesh you don’t always know how to act.

At first, I was paralyzed. Every morning for a year I cried desperately because I did not understand what was happening. I was denying reality. Little by little I gathered my strength and trained myself emotionally to not let them beat me down so easily.

Communicating with my friends and the zines I was sent helped me maintain my strength to not give in to the psychological torture. If before it was non-negotiable to let oneself be ordered around or to be in charge, in prison at certain moments one has to stand firm, the spectrum between giving in and not doing so has its nuances, but the goal is always to not break or become corrupted.

In effect, the goal of prison is to break us, to make us believe that we deserve it, to make us believe that our lives don’t belong to us. But as I lived with compañeras who had been in prison for five, ten, twenty years, I saw their tactics of escape, the ways in which they coped with confinement, in which they confronted the bullshit. I saw the tactics they used to recuperate at least a little bit of their freedom. In prison, like any other place, there are multiple forms of exercising control and multiple manners of resisting it.

Without a doubt, my political posture has changed. It has been nourished by the emotional ups and downs, of sharing experiences with women whose entire lives have been spent surviving prison.

It is not the same to say something as it is to do it. Our practices should be directed by our vision of the world, and we have to assert that vision in our practices, not only with words. Beyond the banners and labels, there is courage, strength, kindness. Taking paths to expand our freedom will undoubtedly lead us into situations of confrontation like this one as well as others. We have to be prepared.

Like the imprisoned compas in Chile say, nothing ends with prison. It is another space of struggle and conflict with authority, a battlefield, filled with manifestations of control and latent abuse. Being on the inside is a chance to demonstrate to them that we cannot be defeated. It is a chance to resist and to mock their chains, their stupid rules, and their double standards.

It is important to know their strategies. There is already a well-developed idea of what prison is, taboos and certain projections. We need to demystify that, to let go of the fear, to not fall into their trap, to stop believing in their function.

IGD: From your experience in prison, what advice might you give to folks who are supporting and accompanying prisoners? What types of support do you feel work well, and what others don’t?

I haven’t directly participated on the other side of the relationship, but I understand that it is a struggle just as intense and exhausting as surviving on the inside.

These are some of the things I saw in people, friends and collectives that were with me and with other prisoners. Many of these things are already known, so maybe I am just reaffirming what has already been done and questioning others.

The economic support is fundamental, particularly at the beginning. Spreading information about the case; preserving strength because even if you don’t want it to be so, the years pass by and the energy runs out.

Maintaining constant inside-outside communication so that what happens on one side of the prison walls can have a resonance and impact on the other; so that our actions become more and more intense and direct.

The legal aspect is important. At the beginning I went through four different lawyers and all of them sold us promises, they got my family’s hopes up, even though they knew the seriousness of the problem. What they wanted was money and to take advantage of the situation.

For that reason, legal support from anarchist, antiauthoritarian, or solidarity lawyers is pivotal. People often think that fighting legally is just to play by their rules, but the anticarceral horizon makes use of a diversity of tools. If we don’t know how the penal code functions, we are lost in a foreign language that operates on our lives.

So long as there are collectives and individuals who are willing to do this work, there is a chance to put up a fight. In our case, Alma Mergarito was there, visiting us, taking care of the paperwork, being present at the hearings. We also remember with affection and respect Pedro Saavedra “Batí.”

The psychological and therapeutic support play a fundamental role for those who are on the inside and those who are accompanying prisoners as well. There are several collective texts made by compas who have gathered some of these experiences of providing support in cases of trauma and violence, to alleviate the wounds of confinement.

I was accompanied by zines such as “Entrenamiento físico en condiciones de encierro” and “Hierbas para la tristeza” by Nicole Rose. Heather Anne visited me every fifteen days for therapy. The long talks and discussions with the compas whose names I won’t mention but who I’ve already let know of the importance of our conversations.

On the other hand, in Mexico “the anticarceral” is not present in the imagination of prisoners. We haven’t done the necessary work of entering into prisons in a more constant manner and getting to know the people, of making and receiving calls, of writing letters to develop networks across prison walls. There is more of a presence of religious and Alcoholics Anonymous groups than there are of groups against patriarchy or groups of feminists.

To a certain extent this is explained by the welfare dynamics of these types of organizations and groups, and their search for followers.

The accompaniment is often very personalized around certain cases of compas in the struggle, but it is clear that the prison is still there, even if some of us are released.

Organizing on the inside is complicated by the mafias and drug trafficking, the powerful groups are not hesitant or afraid in what they do.

IGD: You were detained for a common crime. This configured into the dynamics of solidarity around your case. What do you think about this distinction between common and political prisoners? How do you think the different movements in Mexico can better take on an anticarceral attitude and practice, beyond the idea of just or unjust imprisonment?

Yes, I was imprisoned for a robbery outside of a strictly “political” context. I never denied my participation, although the accusations that were made against me were different than the reality of the action. There wasn’t any regret. Many people refused to accompany me as, voluntarily or not, they made a MORAL distinction between “common prisoners” and “political prisoners.”

To ask for a “revolutionary credential” to know whether someone deserves prison or not is to present oneself as a judge, and that is the foundational belief of prison society.

From anticarceral praxis, being sent to prison is understood from the outset as a political act. It is political because it transgresses a socially imposed limit, because it is a clash with the law, with order. This is not to say that all illegal acts are ethical or desirable, but it is a starting point to understand the function of prisons.

Some movements take up the banner of “innocent prisoners” because if they didn’t, they wouldn’t have support from certain organizations and much less from “civil society.” With this discourse the idea of just and unjust confinement is reinforced, which is another pillar of prison society. Confinement is then considered a solution to social problems, when in reality it is a method of torture and punishment against whatever dissent or “enemy” of society.

On the one hand, it is a topic that we can discuss with less urgency and more in the abstract, dialoguing and questioning: what type of support is needed? Why is there selective empathy for certain cases and indifference to others? Do we only think about freedom for one compa, about a pathway to a world without prisons, or both? Do I demand prison for those who have violated me? If we don’t believe in prison, what type of justice can we construct? There are many questions, and the responses can go on forever.

On the other hand, we need to position ourselves in front of real concrete cases. There are many collectives and groups that are afraid to take a position on this, and that is where the silence begins. It is more common to see individuals acting alone who aren’t beholden to the politics of certain organizations, that is where I see more possibility.

IGD: What is the current status of your case? And your co-defendant Brandy? In what concrete ways can folks show their support?

I was released beneath certain conditions. I have to continually check in and sign for the rest of my sentence and fulfill other bureaucratic requirements on certain days of the week. This has affected my daily life of course. It is as if I can’t truly enjoy myself because of the limitations that have been forced upon me. I haven’t been able to recuperate my time and my activities. It is one more step but it can’t go unnoticed that all prisoners face trauma after leaving prison. In prison, so much is taken away from us, so many tiny, unquantifiable aspects of our existence. After almost seven months free, I still feel that I have lost irretrievable ground in terms of my autonomy and confidence.

In Brandy’s case, the TRIAL is still open and ongoing. This is a double-edged sword because it is possible that he wins his absolute freedom or he can lose it and be returned to prison.

There was a raffle recently to collect funds to cover legal expenses that are on the horizon. There will also be some other activities and actions that still don’t have dates. A fanzine is also circulating, “Narrativas desde el encierro,” that he wrote in prison in the Reclusorio Oriente.

A way of supporting is being attentive to when his trial begins because it will be stressful for him: people can send a message, a letter, accompany him during the court hearings, share information about his case, provide emotional and economic support. In these cases, of course money is fundamental. It is important that he is not abandoned in this struggle.

If you want to get in contact with him, you can write to him on Instagram at: @brranadrenaline.

Here also is the number of the BBVA Bank account in case someone wants to make a donation. Cuenta Clabe: 012180015214659700.

I appreciate the space for dissemination, critique, and mutual feedback. Thanks to all those who resist prisons. Until the last cage is destroyed!

Freedom for Jorge Esquivel and total freedom for Brandy! Absolute freedom for Miguel Peralta! Freedom for Mónica and Francisco! Freedom for Cospito! Freedom for Juan Menchaca!

Fire to the prisons and the judges!