Filed under: History, Interviews, Labor, US

Interview between David Ranney, author of Living and Dying on the Factor Floor: From the Outside In and the Inside Out, and the Industrial Worker, a publication of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW).

In his book Living and Dying on the Factory Floor: From the Outside In and the Inside Out, David Ranney offers a firsthand account of working in a variety of Chicago factories during the 1970s and ’80s. The memoir captures the irreconcilable antagonism between workers and bosses, internal divisions between workers and the ability of workers to nevertheless overcome these divisions through common struggle. Industrial Worker recently spoke with Ranney about his experience and what he took away from it. The interview below has been edited for clarity and length.

Industrial Worker: How did you get involved in factory work?

David Ranney: In the 1970s, a lot of left-wing groups were interested in the activities in factories, because there was a lot of insurgency on the factory floors around the country and we wanted to be part of it. I had to get a job, so I thought, “Well, why not do the factory thing?” I did that for seven years.

How did the struggles between workers and bosses that you depict in the book impact the relationships between workers?

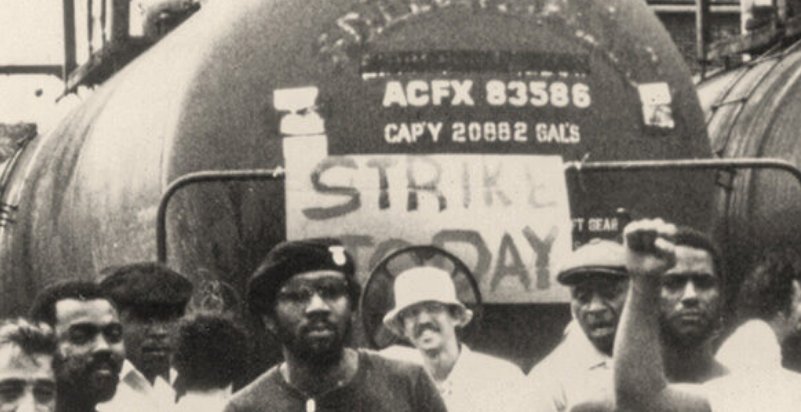

There was an interesting thing I observed about race: Racial tensions were high every place I worked, but when there was a struggle that was really addressing racial questions, people pulled together. For instance, at the Chicago Shortening Factory, the main tension was between Mexican and Black workers, and I was amazed how those tensions went away in the course of a strike.

How did your factory experiences change your understanding of capitalism?

When I left, the factories were starting to go down. They really just collapsed in the southeast side of Chicago. One of the big shifts in capitalism that occurred, of course, is that it is now much more flexible. We have these very long supply chains that go around the world. Having worked in that environment, I really became much more involved with the global dimensions of capitalism.

I saw workers, who were directly confronting, day to day, the exploitation and repression of the capitalist system, pick up little means to resist — things that weren’t always obvious. But they did possibly foreshadow what a new society could look like. We live in a system that’s dominated by wage labor. The key thing about wage labor is the split between capital and labor: working to produce value for capitalists or working for yourself on the things you want to do. There were instances where we were actually working for ourselves.

There was an instance in this chemical factory where there was a huge mess-up, a mechanical issue that shut down production. The bosses were going nuts, wanting us to get it going. A bunch of us got together to plan out what we were going to do. The foreman came in and said, “Why aren’t you guys out there fixing it?” One of the guys said, “If you want to fix it, fix it yourself. We’re going to figure this thing out, and we’re going to work at our own pace.”

We actually enjoyed doing that, but we weren’t doing it for them. That really gives you an idea of how things could be in a different kind of society.