Filed under: Analysis, Capitalism, The State, US

From Unity and Struggle

The following post is the second part in our notes on Trump. Part one can be found here. We’ll look at the limits and potentials of the forces arrayed against Trump in part three.

In our last post, we located the Trump regime within a global right wing resurgence enabled by capitalist crisis and the failures of social democracy. Now we can examine how this resurgence developed in the U.S. context. In this piece, we will explore how conservative hegemony emerged from the crisis of the 1970s, developed through the Reagan years and exhausted itself in the Obama era. We will then trace how Trump builds on the history of conservative hegemony even as he rends it in two, and outline the degree to which the incoming Trump regime stands to deepen authoritarianism.

For decades, the U.S. neoliberal elite legitimated falling wages and living standards by keeping the economy afloat with successive credit-fueled bubbles and playing on white racialist resentments. But this strategy began to collapse with the onset of the Great Recession, after years of erosion. Now the the content of conservative hegemony is turning against itself, and Trumpism in the result. On one side are neoliberal efforts to contract social reproduction, and thereby struggle to renew the profitability of capitalism. On the other side are appeals to white populist nationalism, which increasingly undermine the norms of the bourgeois state and civil society. Both elements have been integral to neoliberal rule, but they can also become contradictory. As they contend in productive tension, they threaten a spiraling descent into authoritarianism and deepening capitalist retrogression.

Trump’s election signals that the turbulent waters of social contradiction have begun to spin faster. To grasp the dangers of this dynamic and how to overcome them, we have to trace their emergence from our own history, starting with the last capitalist crisis.

A New Hegemony from the Wreckage

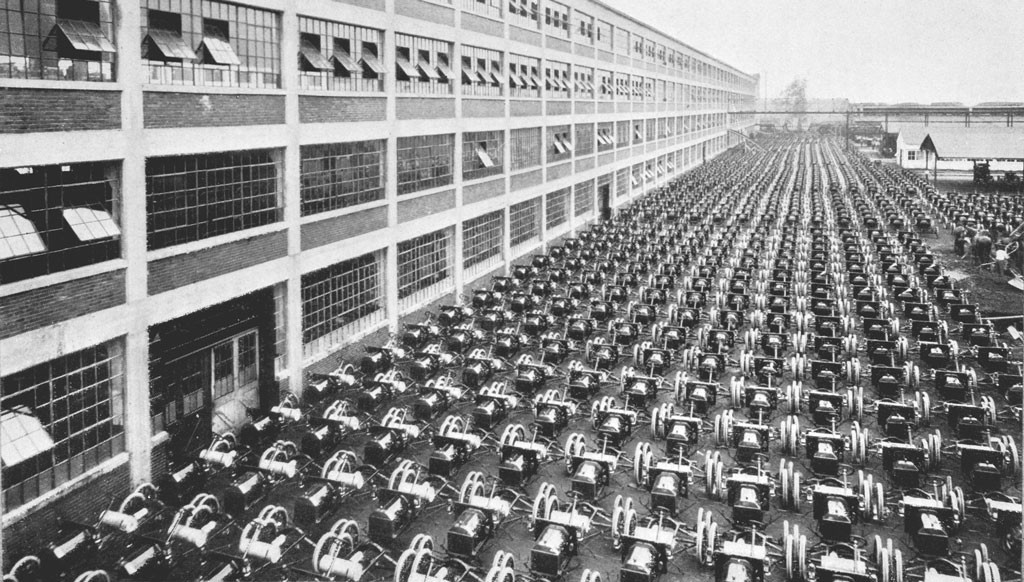

In the late 1970s the U.S. capitalist class faced economic stagnation, rising inflation, and working class revolt in the streets and on the assembly line. In a bid to renew investment, they turned to attacking the costs of labor power, creating a new kind of working class in the process and detonating the Keynesian consensus that had stood for forty years. The 1970s crisis did not lead – as many had hoped – to a revolutionary challenge to capitalism, but to the emergence of a conservative hegemony that would expand and deepen for four decades.

Since the Great Depression, the trade unions, and later the civil rights leadership, had been steadily incorporated into capitalist production and the state. In exchange for labor peace and increased productivity, they had been promised expanded democratic rights, racial integration into civil society, and rising real wages. This period marked the definitive transition to the real domination of capital: the incorporation and reorganization of the whole of society according to the needs of capitalist value production. It resulted in a reduction of labor power, not only in terms of the gap between wage levels and the immense surpluses created at the time, but also through labor’s subjugation as an appendage of automation and the remaking of everyday life. The gap between the condition of workers and the enormous productive forces of capitalism continued to widen, sharpening a key contradiction of capitalism. Though living standards in the postwar period rose for many layers of the working class, thanks to the growing number of cheap consumer goods, this could only continue as long as the surpluses workers generated rose even faster. With economic stagnation in the 1970s – a combination of falling growth and soaring inflation – the material basis for the Keynesian regime dissolved. The capitalist class had to find a new way to rule.

From the wreckage of the Keynesian period, the Republican and Democratic parties forged a new unity that legitimated capitalist attacks on wages and living standards in a bid to expand the cycle of capital accumulation. As mentioned in the previous post, this consensus, sometimes called neoliberalism, involved an interrelated marginalization of the trade unions and civil rights establishment, and a profound recomposition of the working class. The result was a generalization and deepening of contracted social reproduction that fundamentally altered the political and social terrain in the U.S.

The working class was recomposed as capital shifted regionally (moving production to the suburbs or the South) and globally (moving to East Asia, Mexico, and elsewhere). Capitalists and the state took a hard stand against wage increases, setting the stage for decades of accommodation and retreat by the unions. With growing automation, underemployment became permanent feature of the U.S. economy, striking black workers first and hardest. Yet a program of permanent austerity also worked to shred the social safety net established in the New Deal. Finally, an ideological offensive against the gains of the civil rights movement halted the integration of black people into civil society, replacing it with mass incarceration and police terror. This offensive dispersed the collective worker through casualization and atomization, and destroyed the institutions and social fabric of U.S. “social democracy.” In the vacuum, the costs of social reproduction were increasingly borne by the individual worker’s’ wage, providing the basis for a resurgent conservatism.

Conservatism developed not simply as a government policy, but as way of being that expressed and reproduced the new social order. The “American Dream” was transformed from one of “sharing” in national prosperity to a Darwinist meritocracy, in which workers competed all-against-all, and survival became the dominant ethos. Conservatism not only provided an explanation for the collapse of the Keynesian era (“we” had been living “beyond our means”), but also offered cures for the ills that resulted from the new era. In a time when many communities experienced scarcity and social breakdown, right wing Christianity and “free market” ideologies gained traction in a range of institutions, and began to remake the state. Finally, the progressive glorification of workerism from the Keynesian period was succeeded by a conservative populism, which displaced class conflicts onto cultural conflicts, and played on the material divisions within the working class, especially along racial lines. The worker, concerned with the wages and working conditions, was remade into the individual, taxpaying consumer, resentfully guarding his shrinking privileges in an age of austerity.

The Reagan Revolution and The Obama Gridlock

The outlines of this new order emerged with George Wallace, Nixon, and Carter, but it was the Reagan administration that cohered a program and carried it out in earnest. Reagan promised to overcome stagnation and revive American industry, winning the support of “Reagan Democrats” with his promises. But reviving capital accumulation required austerity: a contraction of social reproduction. Reagan thus continued the Carter administration’s policy of high interest rates to destroy inflation at any cost, fueling the deepest recession since the 1930s and sparking bankruptcies and consolidation. He encouraged employers to draw a hard line on wages, signaled by the crushing of the PATCO strike in 1981. Reaganites blamed government regulation and taxes for stifling investment, and their subsequent tax cuts created over a trillion dollars in budget deficits. To continue deficit spending, the government took out national debt by issuing bonds, which in turn fueled international demand for the U.S. currency used to buy them. This dynamic inflated the value of the dollar and raised the prices of U.S. goods on the world market, further devastating manufacturing. Corporate buyouts and asset stripping by Wall Street firms brought the financial sector–now the main source of dynamism in the system–to prominence in the economy and the state.

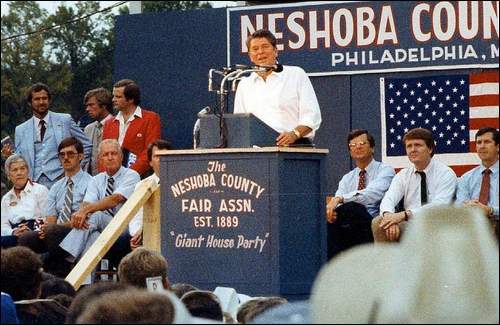

Although the Reagan government imposed a few tariffs to control these trends, American workers were increasingly forced to compete on a global labor market. Wages, benefits, and social programs were beaten down to lower the total social wage. In this way the “Reagan Revolution” stabilized capitalist growth, but not based on the prosperity and integration of the post-war years. Instead Reagan worked to bind many white workers to this program through a reprise of Nixon’s “Southern Strategy,” making appeals to white resentment by expanding “tough on crime” policies and attacking “welfare queens.” Conservative hegemony came to work through a symbiotic combination of contracted social reproduction and white populism. For a time, centrists could plausibly claim that austerity and financialization kept the economy moving, and white resentment could bolster the conservative establishment rather than threaten it.

By the 1990s protectionist sentiment in the government was decisively defeated. The passage of NAFTA, negotiated by the Bush administration but signed by Clinton, was part of a worldwide development in regional economic integration. The vast expansion of global markets, corporations, and credit to facilitate circulation, along with bubble-driven investment patterns, worked to counteract falling profits. Wage stagnation was offset by policies that ensured the importation of cheap goods and encouraged debt-based consumption. It is within this context that Clinton buried the old Keynesian Democrats for good. By appropriating the Congressional Republican positions on welfare, the education system, policing, incarceration and more, Clinton solidified conservative hegemony within the Democratic party.

Obama largely continued this legacy. As the organic links between the classes decayed in the wake of the 2008 crisis, Obama understood more than any politician the urgent need to repair them. His campaign organized itself around the rhetoric of “hope” and “change” in America, counterposed against a decade of economic stagnation and the declining U.S. position in the world order. But the three most notable domestic developments of his administration merely continued previous trends. Obama continued George Bush Jr.’s expansion of executive power in the use of the secret police and military, and against whistleblowers, furthering authoritarian trends within the state. He presided over the reinflation of a historic stock market bubble. And finally, he pushed through Obamacare, which shifted the costs of healthcare onto the individual worker, thereby further reducing the overall total wage.

All the while, the Republican party moved further to the right, continuing a twenty year trend. At the state level Republicans grew increasingly radical with each election primary, bringing to power a reactionary alliance of small town and suburban middle classes. The party extended its power by riding on this wave, and now controls thirty-two state governments against the Democrats’ thirteen. These administrations have focused on destroying the historic democratic gains of women, people of color, queer people, and the working class as a whole. Now Rustbelt states have become “right to work” states, Southernizing former union strongholds; abortion rights and reproductive freedom have been eroded to the edge of illegality; and voting rights have been rolled back nearly to the pre-1965 era. Significantly, the Republicans have also eroded constitutional norms to hold onto power. They have not only enacted extreme redistricting in many states, but now (most recently with Trump’s attempts to purge the EPA and North Carolina Republicans state legislature “coup” against the incoming Democratic governor) are beginning to subject the state bureaucracy and machinery to political tests.

As social polarization reshaped the state, bourgeois institutions tended to become immobilized and advance toward crisis, making the illegitimacy of capitalist rule more and more concrete. For decades polarization was concealed by the “winner take all” electoral system and its resulting two-party duopoly, which prevents alternative parties from emerging that clearly express popular grievances. But even without parliamentary battles, polarization was still expressed through conflicts within bourgeois institutions and the state, as different sections of the political elite capitalized on the growing resentments of their base to wage factional battles.

Amazingly, it is only with the Obama era that the ruling class has become aware of their delegitimation. Under Obama, congressional Republicans opposed every step of the administration, including routine matters such as the appointment of federal judges. “Astroturf” groups like the Tea Party combined grassroots outrage with oligarch funding, and ground to a halt the passage of the federal budget. The result was a slow breakdown of the machinery of government, and a growing inability of the capitalists to govern as a unified class–at the very moment that popular discontent swelled.

Although conservative hegemony faced a series of electoral challenges, none posed a lasting challenge. Jesse Jackson’s “Rainbow Coalition” campaigns in 1984 and 1988 turned out to be the last gasp of Keynesian social democracy (though the Sanders campaign indicates how weak appeals to social democracy can, importantly, still resonate and express mass discontent.) Meanwhile, although Pat Buchanan’s campaigns in the early 1990s were also electoral failures, they foretold of things to come with their economic nationalism, authoritarianism, and white racialist backlash.

Trumpism’s Downward Spiral

Trump is a product of the conservative hegemony that has reigned since the 1970s. Yet at the same time, his racialist economic nationalism also indicates that conservatism itself is growing contradictory. Like currents in a body of water, conservative austerity and white resentment are beginning to run counter to one another. The populism Trump draws upon now poses a threat to the conservative establishment itself, speeding the decay of bourgeois society and threatening to radicalize the conservative program and deepen authoritarianism.

We can illustrate this threat by taking an example from nature: a whirlpool. When two opposing currents flow past one another in a body of water, they naturally create twists and eddies. Often these patterns dissipate–but sometimes they persist. When they do, the column of water where the currents meet begins to spin, drawing the water around it into a circular motion, and lowering its own pressure with the increase in speed. At a certain threshold the fast-moving, low-pressure water at the center of the circle starts to sink, pulling down the surrounding water in a cascading spiral. A whirlpool forms. Water is torn from the surface and hurled against the sea floor. Like a whirlpool formed by contending currents, the Trump phenomenon is fueled by the contradictory elements of conservative hegemony.

In some ways Trump promises to continue the conservative status quo. Despite his incendiary rhetoric during the campaign, Trump’s economic positions are largely standard fare outside of foreign policy and trade. His victory will allow conservative majorities at the federal and state levels to carry out their economic and social program: massive tax cuts for the rich and corporations, further privatization of education and the remaining welfare state, and erosion of women’s reproductive rights, voting rights, and the unions. Trump’s picks for Treasury Secretary (former Goldman Sachs banker Steven Mnuchin) and Commerce Secretary (billionaire bankruptcy king and asset stripper Wilbur Ross) confirm this continuity. It is ironic that Trump, hated by the conservative establishment, has delivered to them one-party rule.

In other ways Trump breaks with conservative norms, especially in his rejection of free trade and globalization. His closest advisers have shaped these views. Steve Bannon, for example, is a former Goldman Sachs banker who grew disillusioned of finance capital’s role in deindustrialization. But we have to be clear about the character of this break. Even if Trump is serious about his populist economic nationalism, it is the least likely of his positions to be implemented in a serious way. It would probably still require a radical deepening of the crisis, and a figure and mass organization more dedicated than Trump (a know-nothing grifter), to carry out such a program. Despite the fact that tendencies toward nationalist retrenchment are growing throughout the capitalist system, Trump will still face serious institutional resistance if he tries to replace trade agreements with trade wars, not only from Republicans and Democrats, but from most of the capitalist class.

Where Trump really advances a new kind of politics, on the other hand, is in giving national voice to white racial resentment and the far right, in ways that lay the basis for deepening authoritarianism. His campaign–more an appeal rooted in attitude, a way of feeling, and a repertoire of ideological gestures than a political platform–provided a vehicle for white masculinist populism that had been latent but growing. Trump trafficked more openly in the language of dehumanization than any candidate since the Civil Rights period. The white nationalists and fascists who rallied around it clearly understood the importance of this phenomenon.

At the center of Trump’s ethos is the idea of American decline. Like other forms of conservatism, Trumpism works to re-forge the link between the white working class and the elite, and reverse the perceived feminization of society, through a vision of national revival. But unlike social conservatism (which aims to combat moral ruin) and neo-conservatism (which aims to dismantle the welfare state domestically and renovate imperial power abroad) Trumpism foregrounds American economic and political decay. Its solution takes aim at immigrants and other racialized internal enemies, as well as elites–vaguely defined as politicians, lobbyists, “globalists,” banks, and urban professionals–who abandoned the working class and enriched themselves in a fit of corruption.

Of course, the economic populism at Trumpism’s core cannot be separated from its racialist terms. Since the election, many analysts have debated whether support for Trump was fueled by class or racial resentment. The answer is simply: both. Because race has always been an organizing principle of the U.S. division of labor, there is no way to express class resentment in the U.S. without touching on race, and vice versa. What the racial dimension of Trumpism does is obscure how the assault on the working class is spearheaded by attacks on workers of color, and hide the predominantly non-white character of the the U.S. working class as a whole. Through the blinders of race, white workers experience class resentment as a quest to restore their lost privileges, a relic of their special deal with capital.

Crucially, Trumpism frames the norms of bourgeois institutions and civil society as an obstacle standing in the way of this restoration. Against them it appeals to a renewed masculinism and authoritarianism. The support these appeals have received tells us that the traditional base of the Republican party is radicalizing. Trump’s supporters are increasingly prepared to accept – even welcome – a leader who bypasses the norms of bourgeois institutions and civil society in order to address the crisis. And while Trump is not interested in overturning bourgeois institutions entirely, he will be compelled to placate the disappointment of his supporters each time his economic policies come up short, most likely by appealing to white racial resentment.

In this way, even as Trump will fail to improve living standards as his voters hoped, he stands to greatly advance anti-democratic politics. Trumpism makes possible a marriage of conservatism with a qualitative deepening of authoritarianism and repression. A downward spiral of far right advance and repression, similar to that at work in many parts of Europe, is now possible.

Millionaire Vigilantes

Whether this downward spiral takes off depends on the mutual interaction of many moving parts. Among these are the shifting winds of the global economy, the organizational consolidation of the far right, and the growth of movements that recompose the working class in combat with capital. A key piece Trump brings to bear, however, are the advisors and appointees he brings with him into state power, and the degree to which they are prepared to make white nationalist appeals and expand repressive state powers. Bannon’s work turning Breitbart into a self-described “platform” for the fascist “Alt-Right” is well known. But a brief survey of Trump’s advisors and appointees shows a more complex and dangerous picture.

Although he was frozen out of the Trump cabinet, Rudy Giuliani was a key adviser to Trump. As mayor of New York, Giuliani launched the “broken windows” policing strategy that criminalized everyday life for black and Latino people, transforming the police into a full-fledged occupation army. Since then he has become a major neo-conservative, anti-Muslim bigot and attack dog for the police unions against Black Lives Matter. Jeff Sessions, who will be Attorney General, has led anti-immigrant efforts in the Senate, providing a platform for grassroots anti-Latino groups, and blaming immigrants — including those in the tech sector — for unemployment and falling incomes. Sessions made his career prosecuting black civil rights activists, opposing the Voting Rights Act, and has expressed support for the Klan. Kris Kobach, Trump’s adviser on immigration, is the architect of Arizona’s SB 1070 and Alabama’s HB 56, which empowered law enforcement officers to racially profile people for their citizenship status and deny undocumented immigrants access to services, including education. Kobach has ties to the Federation for American Immigration Reform founded by white supremacist John Tanton, which provided “facts” for Trump’s anti-immigrant campaign ads.

Trump’s far right cabinet picks extend to education as well. Christian Dominionist and charter school robber baron Betsy DeVos will head the Department of Education. Although Democrats and Republicans share the goal of creating a multi-tiered education system and turning schools into factories, all while siphoning public education funds into the pockets of education industry moguls, they differ in their ultimate goals. Democrats (and some Republicans) want to streamline the education system into simple job training, while the far right seeks to abolish public schools altogether and replace them with Christian schools, indoctrinating children with various brands of christian fundamentalism.

In foreign policy, too, Trump’s appointees express racialist worldviews and creeping authoritarianism. Mike Pompeo, future head of the CIA, is a former Congressional representative and longtime frontman for Koch industries. During his reelection campaign, Pompeo ran racist ads against his Desi opponent, warning voters to “Vote American” with images of John Wayne superimposed on an American flag. Pompeo advocates removing obstacles to domestic mass surveillance, and has called for the murder of Edward Snowden, reinstituting torture, and reversing the Iran nuclear deal.

The most important figure in the foreign policy sphere is Trump’s chief foreign policy adviser, Michael Flynn. Flynn was intelligence chief for the Joint Special Operations Command (the secret arm of the military) and later head of the Defense Intelligence Agency, until he was reportedly fired for his ideological management style. Difficult to place ideologically, Flynn embraced the “axis of evil” framework of the Bush neo-conservatives, but horrified the military establishment by traveling to meet with Putin. It is possible that Flynn (like his son who tweets white nationalist material) finds appealing the reactionary and anti-liberal spirit of Eurasianism, the ideology of the Russian far right, whose connections to Putin are well-known. While the Trump bloc’s affinity for Putin scandalizes the foreign policy establishment, it is consistent with Trump’s eagerness to build ties with Nigel Farage (former leader of the UK Independence Party who led Brexit and campaigned with Trump) and the National Front in France.

Trump’s right wing nationalism goes beyond his most racialist advisers. Trump has appointed five generals to cabinet posts and considered a sixth for Secretary of State, indicating the growing influence of the military over the government as a whole. In fact, many generals and officers campaigned for Trump, breaking a long standing protocol of officers staying out of political campaigns. Many of Trump’s foreign policy advisers and appointments further express the breakdown of the old international order. Trump’s core advisers seem to be anti-NATO, Euro-skeptics, and anti-free trade, upending three components of U.S. geopolitics that have stood for seventy years.

Finally, it is hard to imagine Trump’s success without the new oligarchs that funded him.

The big money backing Trump was provided by Robert Mercer, a billionaire hedge-fund boss. The secretive Mercer is reportedly critical of the Republican establishment for its ties to Wall Street, and advocates a return to the gold standard in monetary policy. Besides Trump, Mercer funds right wing conspiracy theorists focused on cabals of elites controlling America. He originally backed Ted Cruz–whose father is a well-known Christian Dominionist–but switched to Trump as Cruz fell behind. Mercer is also close to Bannon, funding Breitbart as well as Bannon’s opposition research non-profit. The other billionaire behind Trump is Peter Thiel, a neoreactionary Silicon Valley boss. Thiel gained media attention by forcing Gawker out of business by funding Hulk Hogan’s sex tape lawsuit against the online outlet. He believes technological stagnation is the cause of American decline, and appears to argue that innovation can only advance by rolling back democratic rights and living standards by dismantling the historic gains of the working class, women, and people of color.

Both billionaires embody the new oligarchic politics that have emerged since the Citizens United ruling by the Supreme Court, which allows the rich to spend unlimited money on handpicked candidates, thus bypassing the institutional power-brokers of the traditional party structure, and contributing to the polarization of American bourgeois politics.

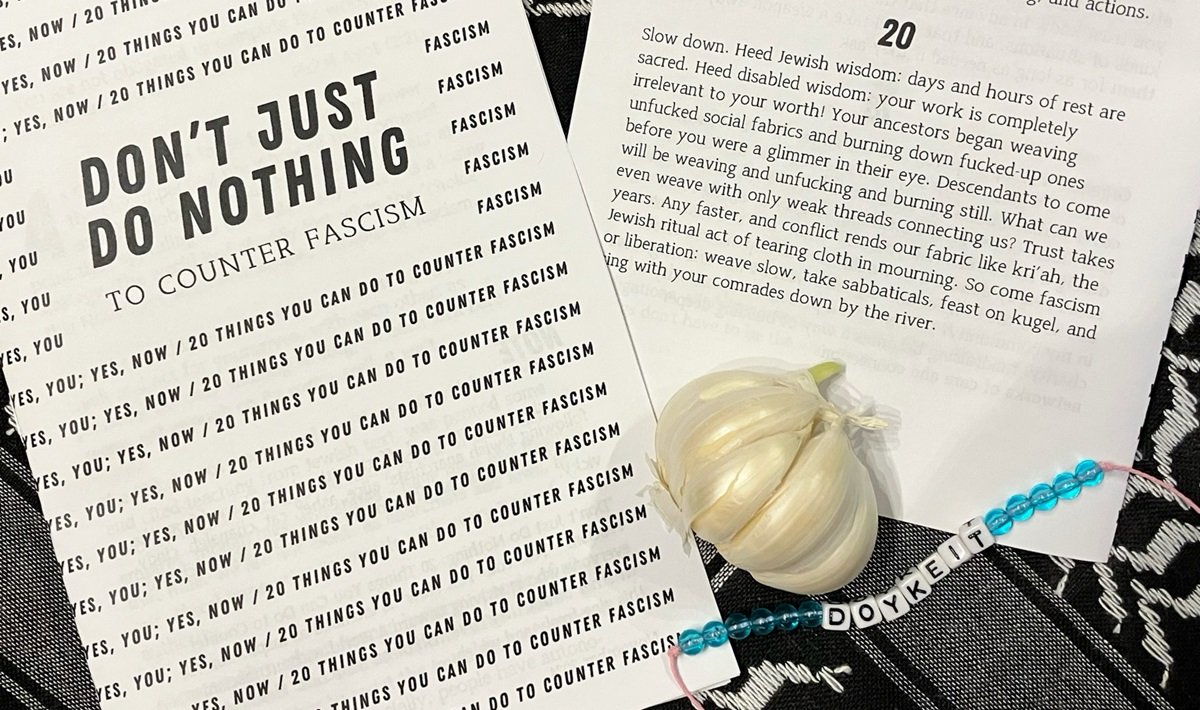

Counter-Currents

More than three decades of conservative hegemony, in partnership with centrist technocrats, have undermined the political and social position of workers, women and people of color. Now it is possible that Trumpism could break the institutional gridlock that has prevented further reductions in the conditions and costs of labor power. Trump’s regime stands to accelerate the broader tendencies of the crisis, quickening the breakdown of bourgeois institutions in the drive to further recompose the proletariat as a low-wage and divided class.

Yet counter-currents remain that could provide an escape from Trumpism’s downward spiral. In the first place, neither Trump nor the Republicans have a broad mandate to carry out their program. After all, not only did Clinton win the popular vote by nearly three million, but Trump received fewer votes than Romney in 2012, a deeply unpopular candidate. Moreover, the election witnessed the lowest voter turnout since 2000, signalling a broad-based rejection of both parties. Nearly half of all eligible voters did not vote, and only 25 percent of eligible voters cast a ballot for Trump.

Secondly, blockages exist to Trump’s plans. Without purging the state bureaucracies, Trump will be forced to contend with established technocrats in many agencies, suspicious of or hostile toward his appointees and policies. Outside the state, organizations such as unions remain legal, continuing to influence wage scales in manufacturing and the public sector in the North and West, and serving as a key cog in the Democratic Party machine. In civil society, queer people have attained democratic rights that were unthinkable a decade ago, and women have established a degree of autonomy that threatens any attempt to reimpose the patriarchal household.

Most importantly, the growing divisions among the capitalists (and middle class) create real openings for an autonomist working class alternative. We will return to this in our next post, but for now it is enough to mention that many new forces–such as the direct action wing of the Black Lives Matter movement and the ongoing Dakota Access Pipeline protests–have been generated through the ongoing crisis and polarization, and are as little contained by the centrist status quo as Trump’s bloc.

Given the ideological constellation of Trumpism, and overall balance of forces, what can we expect Trump to carry out? What limits and potentials do we see in the emergent forces that are arrayed against his regime? We will tackle these questions in the final installment of “Morbid Symptoms.”