Filed under: Capitalism, Editorials, Labor, US

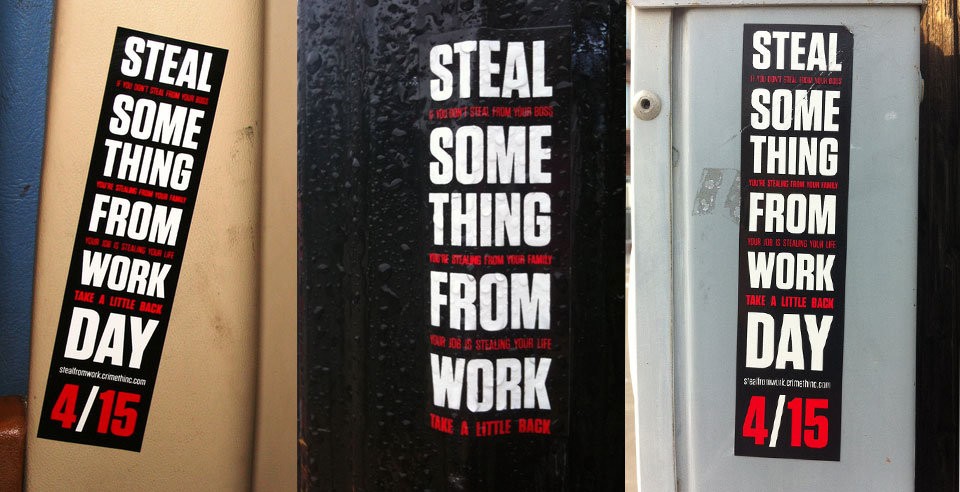

This year, to observe Steal Something from Work Day, CrimethInc. presents three stories of ordinary workplace resistance.

In the first, an employer seeking to cheat minimum-wage employees is outsmarted by an employee who secretly evens the score for the workers. In the second, a proponent of healthy eating smuggles a crucial implement out of a high-security situation. In the last one, a Steal Something from Work Day epic, two low-wage workers—one dressed as “McGruff the Crime Dog“—sneak into a hockey game in a surrealistic example of what our exploiters call “time theft.” We take great joy in celebrating the everyday heroism and good humor with which workers stand up for themselves and assert their dignity in the face of a dehumanizing system.

Employers see workplace theft as a major threat to their profits, if not to the stability of the order that enables them to profit. Traditional doctrinaire socialists ignore it or regard it as a pressure valve that ensures the continued functioning of capitalism, alleging that rather than organizing for the revolutionary seizure of the means of production, employee thieves try to solve their problems on an individual basis.

But we should approach workplace theft as a point of departure for a better world. This widespread phenomenon illustrates how many people don’t actually buy into the social constructs that sustain the current order. Even if theft does play a role in the continued functioning of capitalism—for example, by sustaining workers who could not subsist on their meager salaries alone—it can only serve that function if it takes place in secret, individualistically. When we celebrate it, when we create public forums in which to compare notes and reinforce the shared conviction that we all deserve better than this, we transform isolated acts of rebellion and survival into a basis for the kind of collective revolt that can never be reintegrated into the preservation of the status quo.

We honor the courage of those who refuse to be exploited, of those who seek to even the score. Let’s find each other and take action together.

Click the image to download the PDF.

Correcting Disparities

I live on the border of two states with extremely different minimum wage laws. I worked for a company that moved over the border from the state with the higher (though still not sufficient) minimum wage to the other state. We were able to keep our jobs but we had to take a pay cut. Meanwhile, the boss bought a new house in California and kept her house here as well.

During the process of the move, I happened to find a Post-It note with the admin credentials to the payroll system. Every week for the few months I stayed on after the move, I gave myself and my coworkers a few extra hours of pay to make up for the money they were trying to save.

Nothing happened to me. And it felt like a good deed.

I just wanted to share my story for Steal Something from Work Day.

Liquidating the Bourgeoisie

The morning smoothie is an important tradition at our house. Some grocery stores in our town donate food they would otherwise throw away to the church up the street, and if you get there at the end of distribution process you can lay claim to whatever is left over before it becomes hog food. This gives us access to vast amounts of fruit, which is all well on its way out by the time we get our hands on it. To preserve what’s left, we dehydrate and freeze all we can salvage. The morning smoothie is a joyous celebration of this bounty.

Of course, this plan relies on one piece of essential equipment: the blender. And there came a time when our blender’s future was in question. It had served us dutifully and well; many a frozen banana had met a cruel fate in its gnashing maw. But its time had come to pass on to Valhalla, where it would chew strawberries thrice the size of those in our mortal realm all day and be lovingly soaped and rinsed by Valkyries all night. We all saw its end coming—we could hear the gears grinding. But miserly bunch that we were, we were leaving our next blender—and therefore the future of our house culture—to luck, the invisible hand of the Really Really Free market, or our own future cunning.

At the time, I worked on a ship and was finishing a two-month stint away from home. The day I was leaving was chaotic: we were receiving a truckload of new supplies and preparing for the next voyage. Typically, when we load supplies, we form a human chain and pass boxes deep into the bowels of the ship. On this day, I was located in the part of the chain where I was passing thirty-pound boxes of engine parts past the door to the galley (that’s ship talk for kitchen).

In plain view, on the counter, mere feet away, was the blender.

To protect the identity of this machine, lets call it the NutriStir. I had watched this sleek example of engineering prowess do things our warrior back home could only dream of. At home, we’d present our blender with a daunting task and often it would need assistance to accomplish the feats we asked of it. We’d have to stop it, stir the contents around, fish them out, chop them finer, and generally give the old battle-scarred veteran a leg up. The NutriStir, by contrast, made quick work of everything thrown into it. I had never see it even twitch at a job, no matter how formidable. If we had a blender like that, I thought to myself, our lives would be revolutionized.

Now, it’s common knowledge in shoplifters’ lore that it isn’t a good idea to steal from a place you can’t escape from. Trains, airports, ferries, and the like don’t offer you a way out; you’re in a closed population of suspects if suspicions arise. I admit it: despite knowing that it’s a bad idea, I love stealing from these places. These closed environments enable our exploiters to charge us exorbitantly more than they could if we had alternatives. I’m offended by these case studies in capitalist logic.

That said, it’s especially dangerous to steal on a boat. And a blender is not a small item: I couldn’t just pocket it and walk away. To get it to my room, for instance, I’d have to pass through many different spaces full of my coworkers, some of whom I knew I couldn’t trust, and into a room I shared with two other people. In only a few hours, I would leave the boat to catch my bus out. I thought about it all day, but no solution occurred to me. In my experience, a good theft demands either meticulous planning or a lightning flash of opportunity.

But then I was tasked with taking care of a stack of dirty towels.

In order to get to the laundry room, I had to pass by the galley. Looking through the doorway, I saw that it was empty. I ducked in and threw the towels over the coveted blender. Then I washed my hands in the sink so I would have an excuse if someone had seen me walk into the galley and happened to follow me in. In what felt like a slick move but probably looked extremely awkward, I picked up the towels and unplugged the blender underneath them. I carried my bounty to the laundry room and set down the heap in the corner, hoping to return before anyone else went to put them in the washer.

Then it was time to leave the boat. I packed my bags and said my goodbyes. My hidden treasure lay in the last room I would pass through on my way out. I was hoping to walk in, deftly put the blender in my backpack, and be on my way with no one the wiser.

An empty room would have been ideal. But one of my coworkers, a notable slacker, was hiding in the laundry room watching videos on his phone to avoid working. I hadn’t really come with an excuse prepared, nor could I imagine one that would make sense. “Oh, just left a sock in this pile of dirty towels.” “I can’t find my charger, so I’m checking everywhere.” I could gamble on trusting my coworker, but it was a gamble I didn’t want to take.

“Hi,” I said. He had headphones in and didn’t lift his eyes from his phone.

Often on boats, there is very little privacy. To cope with those conditions, we create our own little bubbles and focus on whatever tiny spaces of mental freedom we can arrange. In the crew lounge, it’s not uncommon to see one person watching a loud movie while another is intently reading and yet another is having a phone conversation a few feet away. I walked in, sorted through the towels, stuffed the blender in my backpack, and walked out. I feel confident my coworker didn’t even register that I had entered the room.

I arrived home victorious and proud. We had the nicest blender on our block. It effortlessly minced concoctions that would have destroyed our previous blender. It’s been well over a year since I brought home this new addition to our family, and I get a tinge of joy every time I hear it grinding away.

Sometimes I wonder what they thought when they discovered that the NutriStir was missing. There weren’t many places it could have gone. There really was no logical explanation other than what happened. Despite the fact that gossip on ships spreads fast and inflates fairly benign dramas to extraordinary levels, I never heard a word about it. I think the most likely answer is that they saw that it wasn’t there, pulled out a spare, and went on with the workday.

Our blender likely has a few years left in it. But if it starts to falter, the ship I work on now has an even nicer blender, waiting to be liberated.

When life gives you lemons… get revenge.

McGruff the Steal Your Time Back Dog

The National Museum of Crime and Punishment. I was an anarchist working at the National Museum of Crime and fucking Punishment.

Don’t let the name fool you. Though located in Washington, DC, it wasn’t a “national” museum in the same sense as the Smithsonian—it was a private collection of chintzy memorabilia and copaganda. The museum exhibited a life-size prison cell, a self-directed polygraph test, and a chronology of the evolution of crowd control weapons—cheap exhibits that could only fascinate a class of people entirely unacquainted with police and carceral violence… and as luck would have it, that’s precisely the class of people who could afford the $25 admission! The crime section of the museum actually had some cool stuff—daring prison breaks, bank robberies, piracy old and new, and no less than a dozen anarchists scattered throughout. But that’s not what the bootlicker clientele came for. The big hits were the police training simulators, “The Cop Shop” (the gift shop—apart from the lobby, the only part of the museum free to the public), and last but, by definition, not least, the America’s Most Wanted television studio.

So what the fuck was an anarchist like myself doing there? It wasn’t because it paid well, that’s for sure.

“Actors! Looking to build your resume? Need a job with a flexible schedule? A new, one-of-a-kind museum is coming to Washington, DC and we are looking for ACTORS to help promote it. Commission bonuses available!”

The Craigslist ad was for actors. I had recently aged out of a youth-empowerment/anti-oppression theater group1 that had changed my life and I was looking to fill the void its absence left in me.

I even did a half hour of diction exercises before the interview, not knowing if there would be a proper audition as well. As it turned out, the “acting” they needed was dressing up either in an orange prison jumpsuit or as McGruff the Crime Dog in order to draw tourists over to a coupon-monger. The coupons were for a discount of one dollar. One miserable dollar from the twenty-five dollar admission. In other words, touristy bullshit—definitely not acting. But hey, I needed the money, y’know, “until something better comes along.” Jobs are such shit. An endless impotent vow to myself to never again suffer that kind of humiliation just gives way to a readjustment (read: lowering) of expectations and self-worth. What else can one do? No, that’s not a rhetorical question. What else? That is the most important question our generation has to answer.2

But hey, at least I wasn’t the only sucker. A friend of mine—who I’ll call Zoe—from the youth-empowerment theater group also showed up, thinking, like we all did, that it was a more dignified résumé-builder than dressing up as a prisoner or McGruff the fucking Crime Dog.

The museum opened right before summer, which is the big tourist season in DC, but it was already sweltering. DC residents like to say the city was built on top of a swamp—hence the “drain the swamp” chant. That’s a myth, but it’s believable, given how insanely humid it gets.

On one particularly moist and muggy afternoon, I was handing out coupons while Zoe, dressed as McGruff, worked the passing pedestrians on the street. There were legions of them because, just a block away, the hometown hockey team was playing in the Stanley Cup semifinals. White suburbanites, sweating in their Capitals jerseys, rushed past us to get to the game, without time or attention to spare for my half-hearted sales pitch. The few that did engage with us were mostly drunk and exclusively stopped to challenge McGruff to a fight.

Why, you ask? During this time, there was a viral news story about an uptown MetroBus driver who, seeing a cop dressed as McGruff, stopped his bus, stepped out, and socked the crime-fighting mascot. The bizarre part of the story is that there wasn’t much more to it than that. No past grudges, not even much of an explanation—just plain old prole-on-police violence. What’s not to love?

As a result, when my coworker worked as McGruff (I unequivocally refused to ever do so), jokers would often approach and say something to the effect that “he oughta watch out.” Normally, it was easy enough to laugh this off and move on, but it was a different story when a crowd of drunken hockey goons began to form around my friend. Breaking character, Zoe took the head off: “I am so over this.”

“Yeah, I’m sorry about these bozos.”

“Nah, I don’t care about them. It’s this damn costume. I’m sweating like a bama up in here and I can’t even get the fan to work. I feel like I’m gonna faint.”

McGruff’s head was wired with a fan that worked exactly 0% of the time that I was employed at the National Museum of Crime and Punishment.

“Damn. Yeah, just leave the head off. And if you want I could try getting you some ice from Chipot—”

Stop. The air dropped out of my voice and my eyes went wild. The gears of scheming began to turn in my head. You could say I froze…like… ice.

Ice. Cool. Cold. Ice. Rink. Hockey. Hockey! ICE. HOCKEY. Arena. Sitting. Cold cool sitting. Arena. Mascots. MASCOTS! MCGRUFF!!!

“No, wait, fuck that, I bet we could get into that hockey game with the McGruff costume.”

Had it been any other coworker, I don’t think I would have just come out with it. But Zoe and I had been through the theater group together. We came from really different backgrounds and parts of the city, but we had talked about deep shit together—race, oppression, growing up. Still, up to that point, we had never been bad together. My intuition told me that our shared capacity to communicate, both with and without words (for all good actors know that language is not just what we say, but how we say it), would make us good at being bad.

“Oh my god, you really think so?” She didn’t miss a beat. That’s how I knew she was down.

“Definitely. I mean, not legitimately, but…”

“Let’s do it.”

“The only thing is Matt and Laura…”

Matt and Laura. Matt and fucking Laura: our managers. About once per shift, one of them would find us on the street and “check up on us,” pretending like they were seeing if we “needed anything,” but both parties knew they were making sure we weren’t stealing back time while on the clock. If they rolled through and couldn’t find us, we’d have to sit through some patronizing interrogation. Fuck Matt and Laura.

“Fuck Matt and Laura. Oh wait, shit.”

“What?”

Matt’s voice startled me and I whipped around a little too fast. Did I betray our coworkerly conspiring? Is there a fucking YouTube channel or something where managers watch tutorials about how to creep up on you out of nowhere? They’re all so fucking good at it.

“Hey you two! Just wanted to check up and see if you needed anything!”

My eyes blurred, tearing up with all the effort it took to keep them from rolling. Luckily, it was a bright day, and my look came off more like a sun-squint than a glower.

“Oh, yeah, we’re all good.”

Laura piped in: “Looks like you’re doing a great job out here. Zoe, one thing, the McGruff costume just doesn’t work without the head, I know it’s hot, but maybe you could just stand in the shade?”

We were saving all the shade for you, Laura.

When my eyes came back into focus, I realized Matt and Laura were both wearing Capitals’ jerseys.

“So glad we bumped into you two. We won’t be back for a couple hours, so if you need anything just talk to Brock, ok? Keep up the great work!”

Brock, the security guard. Brock the Pet Rock, as we called him behind his back. The name had as much to do with his stone-cold demeanor as with the fact that the man barely ever moved. Neither before nor since have I met someone so apparently content to stare, for hours, straight across a gift shop lobby. We didn’t have to worry about Brock. And we no longer needed to worry about Matt or Laura—they’d be occupied… inside the very fucking place we were about to sneak into, oh shit!

Zoe apparently just didn’t give a fuck. Reasonable, given that the stadium was full of thousands of other people to blend in with—and the job sucked. I was a little nervous now, though.

“Risky.”

“What?” Zoe asked.

“This feels risky, yo. Matt and Laura are going to be in there.”

“Yeah, but so are twenty thousand other people.”

“Still feels risky. Let’s take a break and think it over.”

With a silent nod to Pet Brock, we were back in the museum soaking in the AC. It was slow inside. Barely any customers. Zoe hit the break room, but I took advantage of the empty museum to admire the crime exhibits on my own. Bandits, outlaws, escapees: I was surrounded by some of life’s greatest risk takers. Compared to their escapades, sneaking into a sports game was small potatoes. But what was the payoff? The criminals whose stories and memorabilia surrounded me (the ones I took inspiration from, at least) were after a life of riches and adventure, or else fighting for their freedom. Me, I was just trying to kill time.

“Maybe we shouldn’t…” I thought, “Zoe will be disappointed, but to be honest, I kind of need this job.” The pay was shit, but a couple of weeks without it, while searching for a new gig, would have really set me back.

From an enlarged mugshot, Emma Goldman abruptly butted in: “Puritanism is based on the Calvinistic idea that life is a curse, man must do constant penance, must repudiate every natural and healthy impulse, and turn his back on joy and beauty. Our life is stunted by Puritanism, and the latter is killing what is natural and healthy in our impulses.”

“So, uh, what you’re saying is I should skip work and try sneaking into this game… because it could be joyous and beautiful?”

Silence. I walked on, glancing back at Emma’s motionless face. She was still icily staring down her captors. Calvinistic Puritanism?

As I passed the “Great Trials in American History” section, Albert Parsons addressed me from the Haymarket panel:

“Break this two-fold yoke in twain!

Break thy want’s enslaving chain!

Break thy slavery’s want and dread;

Bread is freedom, freedom bread!”

“Okaay… thanks Albert, but I’m all good on bread. Always plenty in the dumpster. But, uh, that was a very inspiring verse. Thanks. Though to be completely honest I’m not really deciding between freedom and slavery, I’m just trying to figure out whether to sneak into this hockey game.”

On the gallows, next to Parsons, George Engel interjected, “As water and air are free to all, so should the inventions of scientific men be applied for the benefit of all!”

“Right… but, like, you mean hockey arenas?”

No reply.

I ambled on through the museum, lost in contemplation. Was this decision so important that the legends of anarchist history felt the need to speak up from beyond the grave and compel me to disobedience and crime? As I mulled it over, I didn’t even realize I was wandering into the “punishment” part of the museum, until I bumped into the glass perimeter. It was the studio of America’s Most Wanted.

Displayed behind the glass were the program’s biggest “busts.” The first one to catch my eye was Sarah Jane Olson. I recognized her immediately because we had celebrated the good news of her recent release at our infoshop’s last political prisoner letter-writing night. Olson did time for charges stemming from Symbionese Liberation Army actions in the 1970s, but she had lived underground for decades afterwards—even volunteering at the Arise! bookstore and infoshop in Minneapolis.

“There you are!”

Zoe. Right. Shit.

“I’ve been looking all over for you, I even asked Brock. Come on, he’s gonna snitch us out if we stay on break much longer.”

“Right. So, back to work or…?”

“What? What about the game? Or are you starting to feel sketchy about it?”

“Well, I was just thinking…”

The glass began to shake. Sarah Jane Olson’s voice broke through, shattering my inhibitions. “I’m with you, and we are with you!” The voices of all our freedom-loving, law-defying, boss-hating forebears rang out, filling the hall with an eerie, deafening hum. As the hum got louder, it filled me with determination. It wasn’t courage—for I was still scared of getting caught—but now I was determined not to live a life of fear, subjugated to the clock and the Sisyphean scam of earning commission. Then the janitor switched off the vacuum.

“Excuse me. I need to get that spot you’re standing in.”

“Oh, right, sorry. We were just leaving.”

Out of the television studio, back through the prison cell replica, past Parsons and the gang, past Emma Goldman, whose eyes, I swear, changed from icy refusal to pedagogical approval as we passed before them. Past Pet Brock, out of the air-conditioned lobby, into the sun. Too much sun and a flower will wilt, but the spell of a warm kiss after a long freeze will bring blossoms.

I come to life.

“Okay! Put your head on, don’t say a word, and just follow my lead,” I tell Zoe.

“Got it!”

We walk up to the first open door with a ticket taker. We try just walking in naturally, but the ticket taker stops us: “Excuse me.”

“Yeah, uh, McGruff here, uh, for a promotional, yeah, you know?” It’s not even a full sentence. And what explanation do I have for accompanying McGruff? Like, this woman is an adult and understands that there is a person inside the costume—why would they need me to walk the mascot around?

But the totality of the spectacle is powerful. She ignores McGruff and just speaks to me.

“The media check-in is at the loading dock.”

“Oh, right! Yeah, uh, where is that again? My boss forgot to tel—”

“Fifth Street.”

“Right, right, okay, cool! Thank you!”

Zoe complains, “Man I gotta walk to Fifth Street in this?” Fifth Street is on the opposite side of the arena. “At least you got time to work on a better line than ‘promotional, yeah, you know?’”

At the loading dock sits a bored security guard with a radio on his desk and a men’s fitness magazine in hand.

To Zoe, quietly: “Okay remember, let me do the talking.”

To the guard, after taking a second to breathe deep and muster all the improv skills I had honed through my years of theater: “Yeah, uh, here’s McGruff, uh, you know, for a um uh promotional, yeah…”

My supernatural abilities are expanding today. Not only can I communicate with portraits, but I can sense, without even being able to see through McGruff’s big plush head, that Zoe is staring daggers at me with the sidest eyes ever.

Without looking up from his magazine, “Sign here and see the media desk back there to find your registration.”

Find my registration? Fuck. Well, that definitely won’t be happening. I might have turned back at this point if I were by myself, but there isn’t really a way to discuss the situation with Zoe in front of this security guard. Best to just move forward, like everything is going as expected. I sign for both of us. I sign “McGruff McDogg” for Zoe. Dude doesn’t care, doesn’t even look.

The media desk sits about 50 yards down into the bowels of the arena, in front of an elevator. As we walk closer to it, I whisper to Zoe, “Wait, is anybody even back there?”

“Man, I can’t see that far in this thing.”

“I don’t think there’s anyone there. Here, walk quickly with me.” But not too quick, lest the first security guard turn around and suspect something’s up.

We get to the desk, and I scan the area—there doesn’t seem to be anyone around. There’s definitely some cameras pointed this way. But there are always cameras in places like this, right? Is this a part of the building they would prioritize during an event? It’s definitely a controlled access area, but…

The chime of the elevator brings me back. Zoe didn’t hesitate when we got to the desk. She just sidestepped it and called the elevator. Go Zoe! The doors open to reveal a tall man with an ID badge, looking very grumpy, and I immediately offer a jumble of excuses: “Oh sorry we were just making sure our names were here in the book I don’t know what happened to them you see McGruff is doing a promotional, uh, you know, thing, and they told us to sign back here they had our names back there at the entrance so I don’t know where the breakdown in communication was but we’re definitely supposed to—”

“What floor?”

Sweet relief—he’s the elevator operator! We rush past him into the elevator, before anyone actually shows up at the media desk.

“I said what floor?”

“Um…” I scan the numbers “Three?”

The doors close. We are lifted into the belly of the beast. Doors open. We’re in.

“YO!”

“I know Zoe, I know. We fucking did it. But come on now we need to find a bathroom and get you out of this costume.”

“What?! No way, man, this shit’s funny. I always wanted to be on the Jumbotron!”

“Not today, you don’t. Remember, Matt and Laura are here!”

“Man, fuck them.”

“Come on, I don’t want to lose my job.”

“Aight fine.”

Looking back, I shouldn’t have protested against the costume. I don’t remember how I eventually quit that job, but I would have never forgotten if it had been by giving the bird to my bosses over the Jumbotron.

In the bathroom, I think over what to do if we see Matt and Laura. Will I even recognize them? All white people in sports jerseys look the same to me. Maybe I can pass it off like we snuck in here to do some high-volume couponing. The halls are empty, though. It’s the middle of the second period, and the game is tied.

Zoe changing didn’t actually make us less conspicuous. We still had to carry around a giant plush mascot head stuffed with a trench coat, and, worse, we are literally the only two people not wearing hockey jerseys. Everyone is wearing a jersey.

We play it safe and go up to the nosebleed seats. But empty seats aren’t as easy to find as I expected. It’s fucking packed, even up here. And for good reason: the game is TENSE. It’s tied 1-1 when we finally take our seats, but almost immediately—SCOOOOOORE! The stadium erupts. Before I know it, Zoe and I are on our feet cheering, though we don’t know whom for.

“WOOOOOO!!!! What just happened?! I’ve never seen a hockey game.”

“What! Are you serious, Zoe? Then why did you want to come here?”

“Are you kidding me? This is way better than work!”

“Well, uh, I think it was the Capitals, because everyone in here is losing it.”

“We’re winning!” Some stranger screams in my ear as she hugs me. Yes, we are.

The rival team—the Pittsburgh Penguins—start off the third period strong. Two goals right off the bat take away the Capitals’ lead, but it brings suspense back into the game. A fight breaks out on the ice.

“Yo! They’re just letting those dudes brawl!”

“Yeah, that’s hockey.”

“Hell yeah.” Zoe is loving it.

With five minutes to go, I start wondering if we should call it and beat everybody to the exit—especially Matt and Laura. But while I’m discussing it with Zoe—SCORE!!!! The Capitals tie it up again. Four minutes left.

“Aw, fuck it. This is too good.” We stay.

The stadium is roaring. The atmosphere is electric. Time slows down for the next four minutes. Not a soul questions whether their tickets were worth what they paid for them. For once during my employment at the National Museum of Crime and Punishment, the calculator in my head stops evaluating whether $8.50/hour is worth what I’m doing with my time. I am more than fine with sneaking in to watch this game and hang with my friend for $8.50/hour. Fuck, this shit is FUN.

Overtime buzzes in and the crowd is LIT.

I explain to Zoe, “Overtime in hockey is sudden death.”

“What’s that?”

“First goal wins. So as soon as somebody scores we out, okay?”

“Kay.”

The whole crowd is screaming their goddamn heads off. Is that Emma’s voice I hear cheering in the stands? Albert’s too!? And George’s? I can’t tell—I can’t take my eyes off the ice. The ice. This is so much nicer than standing around outside in the heat.

Bam! Pittsburgh scores. All the energy is sucked out of the room. My gaze is hypnotically fixed on the ice, along with forty thousand other eyeballs, disbelieving what we just saw. What the fuck is wrong with me? How did I all of a sudden care about this game? Damn, what a rush…

“Hey, we gotta go, right?”

Zoe breaks me out of my daze.

“What? Oh. Yeah.”

We bolt, trying to beat the crowd. But, as we were sitting in the highest section, all the floors below us are full of people clogging the exits.

“Damn, we are definitely stuck. Hopefully we don’t see Matt or Laura.”

“Hey, why don’t we just hand out coupons right here?” Zoe proposes.

“What? We’ll get kicked out or something.”

“So? We’re trying to leave anyway. I’m just saying it’s a bunch of disappointed people who might want something to do now, and we get commission from the coupons, y’know?”

I agree that she has a point.

“Alright, yeah, go get changed.”

The coupons are flying out of my hands. Everyone’s eager to take their minds off the game. Damn, I should’ve brought more.

Two floors down and we’re almost to the exit, when none fucking other than motherfucking Matt breaks away from a conversation and gets in our face, “What are you guys doing in here?!”

“Uh, when the game ended we rushed in, you know—big crowd, lots of coupons.”

“No. No, no. Jesus, you can’t just go into a private establishment and solicit. You’re going to get us in trouble. We need a contract to hand stuff out in here! Get out of here, NOW!”

We turn around and start for the exits.

“Hey! And don’t get caught.”

“You got it, boss.”

- In practice, this theater group was one of the most functionally anarchist projects I’ve participated in. At the beginning of the season, we established agreements—rather than rules—that only passed if every single cast member agreed to them. For the first half of the season, we took part in long, challenging exercises addressing racism, sexism, heterosexism, and ageism—not only discussing them as abstract concepts but also sharing stories about the impact of oppression on our own lives, whether we faced the brunt of it or wielded privilege. In the second half of the season, we broke into small groups, each of which developed a one-act play based on our stories. These plays were then woven into a collectively written, full-length play. For me, the most transformative part was that whenever a problem came up in the cast—some beef, drama, or cliquing—if it couldn’t be addressed interpersonally, we addressed the conflict openly. The experience of working out problems between people from really different backgrounds, people who probably would never have met if not for this theater project, cemented my conviction that human beings have the capacity to live in societies without authority figures.

No one besides myself would have identified as an anarchist or understood anarchism as anything other than Hobbesian chaos. However, through this project, everyone came out armed with the lived experience of collective organizing, consensus process, conflict resolution, and an understanding of power and oppression. While I treasure certain anarchist critical examinations of consensus process, identity politics, and conflict resolution, I lament the lack of attention given to the anarchistic aspects of the ways people often live, albeit by some other name or without a label at all. Everyday practices that reproduce anarchistic values are as important as our wildest revolutionary aspirations, for the latter require fertile ground to grow in—and the former can provide it. ↩

- Years later, a small scandal emerged over the museum paying black youth to stand outside in orange prison jumpsuits, essentially to entertain tourists. For me, this just illustrates how for targeted populations in a white supremacist society, dependence on a wage and imprisonment in a cage are just different expressions of the same thing—different points on the same continuum of oppression. ↩