A historical look at the anarchist movement in San Francisco at the turn of the 19th century.

On the subject of strategy, we have learned all the lessons from the tradition of the defeated. We remember the beginnings of the labor movement. The lessons are near to us…the power of the American proletarians at the beginning of the industrial era stemmed from the development, within the community of workers, of a force of destruction and retaliation against Capital, as well as from the existence of clandestine solidarities.

-The Invisible Committee, The Call, 2003

In recent years, the number of anarchist history books and academic studies have blossomed thanks to the tireless work of AK Press (among others) and the thankless authors and researchers who’ve sold their souls to the academy. For the first time in a over a century, the complete works of Errico Malatesta have been published in English and US anarchists now have access to the original strategies of insurrectionary anarcho-communism, a common-set of practices that thrived between the 1880s and the 1910s.

At the current moment in history, these century-old practices are being revived across North America, although many still remain to be uncovered. Rather than look for national and trans-national structures to the old anarcho-communist movement, we should search no further than our own cities and towns for the material practices that once bolstered our strength. Knowledge of our past deeds have been suppressed for decades, a tactical move on the part of our enemy meant to keep us atomized, and we’re the only ones who can recover it.

As the Invisible Committee puts it, the political techniques of capitalism consist first of all in breaking the attachments through which a group finds the means to produce, in the same movement, the conditions of its subsistence and its existence…in separating human communities from innumerable things — stones and metals, plants, trees that have a thousand purposes, gods, djinns, wild or tamed animals, medicines and psycho-active substances, amulets, machines, and all the other beings in their realms that co-exist with humans…just as it was necessary to liquidate the witches — which is to say their medicinal knowledge as well as the movement between the visible and invisible worlds which they promoted. In order to recover this lost knowledge, we should search directly beneath our feet, and to illustrate how revealing these investigations can be, we’ll look no further than our own back yard: San Francisco.

While many people try to deny it, the majority of the early US labor unions were hotbeds of racism with many owing their initial strength to anti-Chinese hysteria. This was certainly the case in San Francisco during the 1870s, a period that makes the Italian 1970s pale in comparison. For anyone who might have been an anarchist, the struggle of 1870s was less against bourgeois capitalists than it was against the pimps, crimps, ship-owners, and racist lynch mobs of the labor movement. In short, the struggle was against local tyrants who preyed on the most vulnerable.

Since the boom of the Gold Rush in 1848, one neighborhood held strong against these racist mobs and maintained its interracial character well into the 20th century: Telegraph Hill. First populated by prostitutes from Mexico, Chile, and Peru, this hill withstood numerous racist attacks in the 1850s and 1860s until it became a veritable bastion of freedom protected by clandestine forces. Unless they were from the neighborhood, no one ever went to the eastern slope of Telegraph Hill. It was far too dangerous.

A “street” on Telegraph Hill.

Situated just above the waterfront and far removed from downtown, the eastern slope of Telegraph Hill provided an ideal sanctuary for vulnerable populations fleeing the racist hysteria of the land-based trade unions. It also became a refuge for honest sailors. Given the international scope of their work, sailors tended to be far less racist, if not out-right anti-racist, and they remained unorganized throughout the anti-Chinese progroms. By the 1880s, the federal government had crippled the racist demagogues by officially outlawing all Chinese immigration to the US, depriving these union bigots of their main scapegoat.

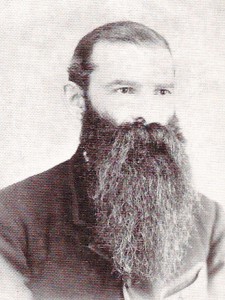

The collapse of the anti-Chinese hysteria did nothing to change the racist character of most San Francisco labor unions, although it did allow an opening for a certain anarchist sailor. While anarchists affiliated with the first Black International had lived in San Francisco since the 1860s (the decade Bakunin first arrived in town), their first major initiative was spearheaded by a Polish Jew named Sigismund Danielewicz, a man who’d just returned from organizing against the San Francisco sugar barons on their Hawaiian plantations.

Sigismund Danielewicz, found of the Coast Seamen’s Union.

He waited out on the waterfront one night, stood beneath a gas-lamp, and called for the sailors to gather around. In a frantic speech, he denounced the crimps who sold off their labor to the greedy ship-owners and called on them to form a union. By the next evening, March 6, 1885, Sigismund had recruited over 400 members into the Coast Seamen’s Union. Rather than try and take over existing racist unions, the anarchists appear to have chosen the profession most conducive to anti-racist anarchism. As we’ve noted, sailors traveled the world and worked alongside men of every race and color, partially immunizing them from common prejudices. Beyond this, the only legal slaves still allowed in the US were prisoners and sailors. When faced with a tyrannical captain, sailors could either engage in mutiny (an illegal act) or submit to the captain’s brutality, making them official slaves (at least while on the seas), a fact acknowledged by a few liberal politicians of the era.

The crimp system further enslaved the sailors by extorting a percentage of their paycheck in exchange for placement on a crew. There was no way for a sailor to find work on the San Francisco waterfront unless they were crimped out by these agents of the ship-owners. For all these reasons, the anarchists chose to focus on the sailors, and by July 1886 their union had grown to over 2,000 members. For the first time in the city’s history, sailors could find work through a union hiring hall rather than be gouged by a crimp. A long and bloody history followed the creation of this anarchist union, but the main point is this: the anarchists targeted an unrepresented and heavily exploited workforce to create their first inroads into the local labor movement. While this union materially benefited all sailors by cutting out the crimps, it also materially allowed the anarchist sailors to travel the world with a valid union book. Right off the bat, the San Francisco anarchists were sailing the high seas.

SF Dockworkers

In years to come, San Francisco would be one link in a long chain that extended from Lisbon, Buenos Aires, Valparaiso, Vancouver BC, the far reaches of Alaska, the frozen shores of Siberia, the Yangtzee River of Imperial China, and every port in between. Thanks to this transnational net-work (as it was spelled back then, by sailors), the remnants of the Black International were able to circulate between the continents and establish concurrent unions in the major ports. While it was easy for anarchists to obtain union sailor books through similar methods, they still had to face down brutal captains.

One local rebel, a teenager named Enrico Travaglio, witnessed a captain shoot down a fellow sailor and was told to keep his mouth shut. Rather than suffer this tyrant any longer, Enrico jumped ship in Siberia and made his way down to China in 1890. It was on the Yangtzee River that he met a friend of Elisee Reclus, the famed anarchist geographer, and Enrico was hired to pilot his boat for a cartographic expedition into the center of Imperial China.

When he returned to San Francisco in 1894, Enrico had become a committed anarchist, although bad news awaited him at home. In his absence, Enrico’s mother Giussepina had passed away, leaving him alone with his step-father Cesare, an anti-religious newspaperman from Milan. Perhaps to deal with their pain, these two men utilized Cesare’s printing press to produce San Francisco’s second anarchist newspaper: Secolo Nuovo. It was printed in modern Italian, unlike Sigismund Danielewicz’s The Beacon, the city’s first anarchist newspaper. Its audience was primarily the growing Italian population of the Latin Quarter, the neighborhood directly behind Telegraph Hill, while The Beacon was mailed out to English-speaking anarchists across the US. Danielewicz himself was fluent in Italian, although most local anarchists could only read or speak one language. In any case, he stopped publishing The Beacon in 1891, leaving Secolo Nuovo the only anarchist paper in town.

While it was a weekly publication between 1894 and 1906, no more than 2000 copies of Secolo Nuovo were ever distributed per issue. The paper was subsidized by friendly merchants (Chinese, French, Spanish, Italian) taking out ads for their businesses along with clueless Anglos who didn’t realize they were financing an Italian insurrectionary newspaper. Back then, modern Florentine-based Italian was still a language of the upper classes and dialect was the preferred language for many “Italian” immigrants. In this regard, composing the paper in Italian might have been a way to communicate to a broad audience, although it could simply be modernist elitism no different from contemporary versions. Either way, Secolo Nuovo definitely made a splash in the Latin Quarter and riled up the Italian bourgeois with its fierce and unrelenting criticism. While the non-literate, dialect speaking “Italians” were shut out of this conversation, their interests were certainly served by Secolo Nuovo, a paper that ridiculed the rich prominenti of the Latin Quarter and their exploitation of recent immigrants.

The Latin Quarter, 1900, facing Telegraph Hill.

Secolo Nuovo was joined by Free Society in 1897, an English-language anarchist journal run by the Isaak family. After escaping a police crackdown in Odessa, this Ukranian family reunited in Portland, Oregon where they started The Firebrand newspaper with several other anarchists. When the editors were jailed for publishing an “obscene” Walt Whitman poem, their paper was discontinued and the group disbanded. Most went north of Olympia to the anarchist commune in Home, Washington while the Isaaks moved to San Francisco and started Free Society. Emma Goldman was close friends with the Isaaks, just as she knew Enrico Travaglio, and all of them were arrested together in Chicago, charged with conspiring to assassinate President McKinley in 1901.

Before he was arrested, Enrico Travaglio had left San Francisco with the Isaaks in 1900 and worked on their paper in Chicago. He eventually moved to Spring Valley, Illinois where he collaborated on another paper with two Italian anarchists, Ersilia Cavedagni and Giusseppe Ciancabilla. This couple fled the Italian Kingdom in 1898 and settled in Patterson, New Jersey, the headquarters of North American insurrectionary anarcho-communism. In this bastion of freedom, Giusseppe served as editor for La Questionne Sociale, the most popular Italian-language anarchist newspaper published in the back room of a bar at 325 Straight Street. Errico Malatesta was the paper’s next editor and the insurrectionist Luigi Galleani would later take over, proving the depth of these trans-national connection.

Offices of La Questione Sociale and IWW Union Hall, Paterson, New Jersey, 1908

Giusseppe served as editor of La Questionne Sociale from 1898 to 1899 while his partner Ersilia Cavedagni joined the anarcho-feminist Gruppo Emancipazione della Donna and performed plays in their Teatro Sociale. During their years in Patterson, a local anarchist named Gaetano Bresci traveled to Milan and assassinated King Umberto of Italy, bringing attention to their insurgent city. Shortly after this, Ersilia and Giusseppe moved to Spring Valley, Illinois where they’d come to meet Enrico Travaglio, editor of Secolo Nuovo.

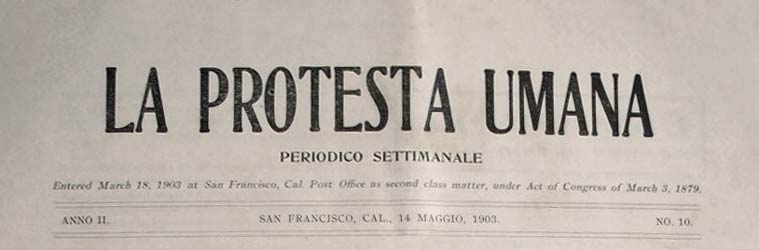

Giusseppe was arrested in 1901 along with Enrico, Emma Goldman, and the Isaaks, although Ersilia remained off their suspect list. After being released, Enrico, Giusseppe, and Ersilia returned to San Francisco in 1903 where they began publishing La Protesta Humana. Not only did they start another anarchist newspaper, Ersilia began organizing public festival and performances to promote their cause. These open-air plays, speeches, and picnics came at a time when anarchists were losing interest in the union strategy, although it had taken them nearly two decades to get there.

After the creation of the Coast Seamen’s Union in 1885, the San Francisco waterfront was paralyzed by maritime strikes in 1886, 1892, 1893, and 1899, culminating in the Great Waterfront Strike of 1901. After the first sailor’s strike in 1886, it was clear that a port blockade could paralyze the economy of an entire major city. This tactic was further elaborated by Errico Malatesta in 1889 during the Great Dock Strike of London where he helped the unorganized dock workers form a union that shut down imperial London for an entire month. This success led Malatesta to advocate forming unions of unorganized workers, infiltrating the labor movement, and building towards a general strike.

According to this strategy, wage gains were incidental to the grander project of paralyzing the economy and seizing vital infrastructure. All the delusions about “stable economies” and “fair workplaces” are products of the 20th century. In the days of insurrectionary anarcho-communism, the workplace was a site to be infiltrated, pillaged, seized, and either destroyed or re-purposed. There was no hope of creating fair capitalism, nor was there any transition period to a worker’s state. As the Invisible Committee puts it, the overthrowing of capitalism will come from those who are able to create the conditions for other types of relations. Therefore the communism we are talking about is the exact opposite of what has been historically termed “communism,” which was mostly nothing but socialism, a form of monopolist state capitalism. Communism is not made through the expansion of new relations of production, but rather in their abolition.

SF headquarters for the Coast Seamen’s Union, renamed in 1891 to SUP

This remained the dominant strategy for many years, although the Great Waterfront Strike of 1901 disillusioned many San Francisco anarchists. After organizing all the maritime trades into a single federation, the unions shut down the waterfront and paralyzed the city for three violent months. Even with President McKinley assassinated by an anarchist, the unions kept up their pickets on the waterfront and engaged in roving gun-battles on Market Street. When it was clear the strike would end in civil war, the governor threatened to bring in the state militia and scared the current head of the Coast Seamen’s Union into surrender. To make matters worse, the disillusioned unions renounced the general strike and voted the Union Labor Party into power. While this elected Party effectively outlawed scabs and private detectives, their officials took bribes from the high-capitalists and forbid the Labor Council from approving any wildcat strikes.

When the Paterson anarchists arrived in the Latin Quarter in 1902 with their street festivals and park performances, it must have surely been a relief from the tedium of union labor. After decades of the waterfront organizing strategy, the anarchists had been betrayed by their very own sailor’s union, and many looked outside the workplace for a path forward. These outdoor festivals were proof that anarchism could be furthered on the streets of their neighborhood rather than on the job where every stolen hour would only enrich the capitalists. This era reveals the split between organizzatori and anti-orginizzatori, although history shows they all worked together long into the 1920s. This split may even have been exaggerated to catch police informants, and by all accounts, their ranks were never infiltrated until Donald Vose of Home, Washington betrayed his anarchist mother in 1914. This snitch was later depicted killing himself in The Iceman Cometh by Eugene O’Neill, a classic American play-write who died in 1953 with an unfinished play about Errico Malatesta in his drawer.

Between 1903 and 1905, the anarchists of the Latin Quarter began providing supplements to their newspapers that included texts in other languages. One of their publications was printed in French, Spanish, and Italian, providing immigrant their neighborhood with a Rossetta Stone they could use to decode each other’s languages. In 1905, the Mexican anarchist Praxedis Guerrero arrived in San Francisco and began publishing his short-lived Alba Roja, a Spanish language newspaper aimed at local immigrants. Praxedis and his two friends found work as longshoremen on the waterfront, proving there were still many radical connections to the maritime trades. According to local legend, Praxedis and his friends hung out at Luna’s Mexican Restaurant, a well-known gathering spot for sailors and longshoremen. Despite the downfall of the Great Waterfront Strike, the anarchists never relinquished their sway among these maritime workers, nor did they give up their sailor’s union books.

The only known picture of Luna’s Mexican Restaurant.

Not only had Bakunin passed through San Francisco after escaping imperial Russia, the port had been used by Emma Goldman to smuggle weapons to both the Philippine and Russian insurgents. Elisee Reclus utilized the waterfront in his journey’s across the Pacific, just as many Russian refugees landed there after the collapse of their 1905 revolution. San Francisco went on to cultivate both Chinese and Japanese anarchism, harbored the blossoming IWW, and rivaled only Paris in its cultural impact. In short, San Francisco was a safe harbor for anarchists fleeing repression and a center of resistance for the international movement. It joined dozens of other North American cities in the global anarchist struggle, each with their own stories as rich as this one. Their strength lay in their particularity, not their uniformity, and when combined they were capable of changing history. These anarchists were generally our grandparents, great grandparents, or great-great grandparents, making their pasts easy to trace for those who are curious. Matters get more confusing in San Francisco.

The old anarchist Latin Quarter came to a fiery end when the Great Earthquake of 1906 set off an inferno that burned nearly all of city, including the official records dating back to 1848. Old identities were erased, new identities created, and suddenly everyone came from San Francisco. Oddly enough, one of the few neighborhoods to escape destruction was the rebel bastion of Telegraph Hill, proving its resilience against all opponents, even earthquake and fire. According to legend, it was saved by the neighborhood dousing their houses with red wine, although the story’s far more complicated.

With that in mind, we’ve offered this short video about two anarchist women who lived on Telegraph Hill in the time period just described. A lot of evidence supports their legends, although only a single picture remains of Isabelle Lemel Ferrari (taken by Jack London). In the year 1914, Isabelle and Enrico Travaglio conceived a daughter they told no one about, mostly because Isabelle didn’t want a husband, lover, or father. Isabelle named her daughter Fulvia but soon left her in a Northern California commune to go aid her comrades in Russia. The rest of the story is described in the video, although we’ve utilized clips from the San Francisco noir-film Thieves’ Highway to act as an allegory for Fulvia Ferrari’s story.

There are no known pictures of Fulvia, nor if that’s actually her name, and it’s possible she’s still alive, making her 103 years old. Her mother Isabelle’s legends are well known from the history of the Ukranian anarchist movement, although the only glimpses of Fulvia swirl around in the Beat era, get doused with LSD in the 1960s, shot up with heroin in the 1970s, given a market value in the 1980s, turned into Hollywood movies in the 1990s, and rendered digital in the 2000s. Some scholars say Thomas Pynchon wrote about her in his novels, while others claimed she knew Philip K. Dick and Ursula K. Le Guin.

It’s hard to know what to believe, but we prefer the stories of annoying people at local cafes and old women sitting at bus-stops on warm evenings. Some of them say Coit Tower of Telegraph Hill is the same as the Sacre Coeur of Montmartre, a victory column over vanquished territory. They say Isabelle and Fulvia’s house on Telegraph Hill was destroyed in the 1920s and that Coit Tower’s shadow falls over its ruin. If one travels there today, that portion of the hill is covered in trees, plants, vines, wild parrots, and sculptures. There’s no plaque to mark any of this, just a few cryptic statues, offerings, and monuments that confirm all the wingnut’s stories.

The “devil-horned mermaid” of Telegraph Hill.

We hope some material practices have been revealed through this essay that might prove useful in the present moment, just as we hope the video illustrates how effectively US radical history was suppressed by the victors of the twentieth century. We encourage our readers and viewers to investigate their own North American cities and connect the dots between 1879 and 2018. Between these two dates, our miserable present came into being, although so did the secret to its reversal. San Francisco was ripped apart by the high-capitalists as punishment for its rebellious history, just as they try to defile every center of resistance that truly threatens them. As we move into this turbulent future, we hope you can take a moment and listen to what the past is saying. As we’ve demonstrated, the ghosts of the defeated are handing us weapons at every moment. All we have to do is take them up. As the Invisible Committe wrote, we believe there is no revolution without the constitution of a common material force. We do not ignore the anachronism of this belief. We know it is both too early and too late, which is why we have time. We have stopped waiting.