Filed under: Anarchist Movement, Announcement, Anti-fascist, Featured, Publication

Long-time anarchist author and organizer Cindy Milstein presents a collection of stories about resistance and grief.

Somehow, “antifascist grief” doesn’t roll off the tongue like the phrase “climate grief,” but perhaps it needs, if not a name, to at least be named. To be acknowledged. To step out of the same shadow of denial that seems to make it hard for so many people to even decisively say “fascism.”

Maybe that’s because making do-it-ourselves time, space, and rituals for grief is, in general, still so difficult. Still so hidden away, individualized, or private. Still so almost forbidden to extend beyond certain moments, like a funeral, or certain categories, like loved (human) ones. Or because it’s so huge, amorphous, and overwhelming—a daily onslaught of bad news—that it’s tough to even recognize the feelings of grief. We say instead “depressed,” “hopeless,” “scared,” brushing off the loss. So much loss. Or we hurt ourselves and/or others.

Perhaps we don’t have words for the specificity of the grief that accompanies fascism because its genocidal logic and practices are too monstrous for a “simple” thing like mourning.

Yet we have ghosts. Our ever-restless, unquiet dead lost to past fascisms. They haunt our bodies and tear at our hearts and rend the fabric of our lives. They cry out for vengeance. They also cry, issuing a communal wail of sorrow and rage that shreds the veil between the dead and us living, magnifying our grief backward and coloring the present ash gray.

What we anticipatorily grieve is something that has already happened, and as if to us. It is carried in our bones as something our ancestors didn’t want to leave us as their legacy, but fascism forced it on them. If we’re lucky, we carry the deep muscle memory of resistance too.

What if we dared to hold hands with these ghosts—our ever restless, unquiet ghosts against fascism—as a bridge to aid them and ourselves to mourn out loud, rebelliously and collectively? To let their blessed memory spark a blessed flame to illuminate the patterns of antifascist grief we all seem to be weighed down by these days, versus suffering on our own? What if, by naming and honoring our grief under Christofascism, we see our path forward together in ways that break some of the patterns that are breaking us and could instead better break fascism?

At the beginning of the pandemic, a friend remarked that the most compelling and insightful works of literature about past eras of mass death often took decades for the survivors to write. That stuck with me: that it’s no easy task at all to process the losses from a genocide, for instance, along with the trauma and grief it generates in painful abundance. It’s harder still to know what to say, and in a way that resonates with others as somehow speaking truth to the horror of what was perpetrated, while preserving whatever scraps of our shared humanity managed to outlive it.

Maybe it’s too early to speak of our “antifascist grief,” then, when we’re in the midst of all that’s causing it, or when we’re likely only at the beginning of this catastrophe(s).

Yet it seems crucial to try, even if only to swap inklings of how grief is touching us now and thus know we’re not alone in our feelings—as many of the pieces in this zine underscore. And from there, sketch out—even if in tentative strokes—how it’s (re)shaping us, where it’s taking us, what it’s calling us to do and not do. Rather than wait until a time when we might become the unquiet dead, needing to torment future generations into seeing and contesting protofascisms before it’s too late, it’s imperative to embrace our antifascist grief so as to never forget, to borrow an anarchist saying, that “our hearts are a muscle the size of a fist. Keep loving. Keep fighting.”

—Cindy Barukh Milstein

1

First, there’s the crowds of strangers. The starving Palestinian children flickering past my screen—that screen built on the blood and sweat of Congolese children.

Second, there’s the friends of friends, whose stories I hear, but will never be a part of. Jack, who helped install the bathroom cabinet in the Big Idea Bookstore. Jude, who went to Cook Forest and had to break into a cabin she paid for. Casey, who Miles thought would live longer, but she died before he could answer her question.

Third, there’s the graveyard of beautiful, impossible pasts, presents, and futures. I imagine my friends without their battle scars. I imagine a world full of plants mingling on the sidewalk with solar panels, and wildflowers instead of lawns. I imagine what my childhood could’ve been like.

A while back, I ordered some zines from Filler Distro. They came wrapped in a poster. The back of it was about someone named Corinne “Tension” Cuyler—all the projects she was a part of and her importance to the writer’s life. The front had pictures of graffiti created in her honor and property destruction done in her name.

I’ll never stop grieving as long as I live—the kind where the loss wells up so bad, I can’t leave the house, sure, but also the kind where I burn. Every genocide, every suicide, every dull and painful existence is a murder by the state and capital. I refuse to forget that. I refuse to let anyone else forget it. Most of all, I fucking refuse to let anyone else go through that shit. I write and distro food and treat strangers with kindness. I do it for the ghosts hanging over my shoulders, the living dead, and myself. We’re all we’ve got.

—Ben

2

Grief is a tightrope I walk. On the one end, there’s the seemingly surreal amount of suffering, loss, death, pain, and hate. On the other, the connections, love, resistance, and refusal of my networks of kin and comrades. For my own well-being, balance is essential. To fall off this tightrope means to enter into crisis. And crises for me are the hopeless places of despair, suicidality, and addiction. I do not want to go back there, for I’ve worked too hard to get out.

This moment is challenging: it seems incomprehensible, yet demands that we live it. To accept reality yet not consent to its impositions is a difficult proposition. To be awake in a world awash in pain is to risk drowning in it. So I must set boundaries. I limit my intake of news. I make space for play. I reach out to others.

At my best, all I have done is say, “Friend, you don’t need to carry this alone.” I believe it is through collectively carrying the infinite weight of stolen lives, the weight of loss, injustice, fear, genocide, state terror, and fascism, that we forge collective memory. It is how we fight back against forgetting. And it is how together, we can walk forward, balanced in defiant grief. No one can hold all of this alone. We must all lend a hand to keep one another from falling.

—Scott Campbell

3

i need to laugh because i’ve exhausted my rage. i’m not sure where the anger has gone, and i’m nervous i’ve lost sight of laughter too. i’m not sure whether that’s because i have been angry for so long that i’ve depleted the reserves of my rage, or because i can now only choose between apathy and resignation. there’s comfort in the certainty of anger, but the depend-ability of fury is not enough. i’m tired, and i can’t fall asleep because i think the state is keeping a closer eye on my friends than i am. our grief demands the impossible task of reconciling that our solidarity moves slower than genocide. i’m scared, yet i’m blessed with the struggle, even when i struggle to feel.

—JOTA

4

I’m a hospice music therapist. Every day I bear witness to the grief of the dying and their loved ones. I sit with them in their time of fear, anger, denial, and sorrow—not just to acknowledge and validate their grief, but to give them an outlet to express it.

Yet I also see and feel the deep grief of the world around me. I can’t help but make these connections. To bear witness to genocide, climate disasters, and fascism.

Instead, we’re all expected to move on. Set our pain aside. Go to our jobs and continue to feed the war machine in some endless cycle. But what I’ve learned through my work is that grief doesn’t like to be stagnant. It doesn’t like to be invisible.

Fascism tries to take so much from us, including making us feel alone. It has a much harder time prevailing, though, if we’re united. Grief is a binding force. It ties people together from every walk of life through this most human of experiences. It shows us that we are interconnected; it builds community.

We have the power to channel our losses into music, art, prayer, poetry, organizing, and so much more. Taking the time to honor, express, and share your grief is rebellious. Don’t let anyone take that from you.

—L. Hillebrand

5

When the news broke about Tennessee’s gender-affirming care ban, I was at a queer youth leadership program, and my trans friends and I hosted a grief space to process it. We spent most of the night discussing our fears and anxieties. Then we moved toward collective care: hate-watching low-budget straight rom-coms, doing each other’s hair and nails, and writing tragically terrible poetry.

From the outside, it might have looked like an angst-driven teenage gathering. But as the evening wore on, little sparks of hope started to appear.

We spoke of mutual aid efforts in our cities that are trying to support youths like us, spaces that have made us feel safe in the past, and the trans futures we envision. Those among us who hadn’t organized before came away with suggestions. We all promised to crowdfund for each other’s HRT or help each other travel across state lines if needed, and hold each other through these anxiety-ridden, painful times.

I also met someone that night who became one of my closest anarchist comrades. Yesterday, when we both began spiraling downward about the latest anti-trans news, we reminded ourselves to talk about the anarchist projects we want to start in resistance to that. She’s trying to set up a mutual aid group to support trans youths with housing; I’m trying to create a similar thing for trans youths navigating coercive control. Both of us are still animated by the grief space and the hope it generated for us that evening, and thanks to the trans community we found in that darkest of moments, we’re now able to dream in more liberatory ways.

—mk zariel

6

Last summer at our student encampment for Palestine, I shared a prayer for sadness, from Siddur Lev Shalem, that has long been meaningful to me. I knew that as written, the prayer wouldn’t serve our self-organized community: not only does it speak of grief as an individual—as opposed to communal—experience, but the prayer asks Hashem to return us to a place of happiness. Given that we were all witnessing an ongoing genocide in Gaza, it felt wrong to ask for our brokenheartedness to be transformed into joy. So I changed it to ask Hashem to “witness” our grief and help us understand its causes, and give us the strength to not turn away from our sorrow but instead continue the struggle for the people of Gaza and Palestine.

It was a profound moment, opening me up to witnessing even more grief—globally and locally, collectively and personally. I realized that this sadness is not mine alone to carry. Now I am holding it with others, and together, it is part of our communal bond. Our moments of shared joy are brighter because we carry so much pain together.

Just as engaging in mutual aid transforms one’s material relations to others from transactional to reciprocal, from charity to solidarity, it’s transformational to be with others in our mourning. I’m not grieving “for” others but rather “with” them.

My initial intuition has been reinforced by encounters with Buddhist, Jewish, and anarchist texts that speak to the inevitability of loss and suffering. They, like my community, teach me to embrace grief.

—Shamma Boyarin

7

For the past two years, those of us affected by ME/CFS, along with relatives and friends who came in place of their dead or those too sick to attend, have demonstrated together. We’ve held mourning protests, accompanied by speeches over loudspeakers, singing, and occupying Leipzig’s central square by laying down. For a lot of us, laying in bed in a dark room is our daily reality. Our grief would remain hidden and forgotten, missing from public life and frequently “even” radical events, if it weren’t for these intentional moments of our own making.

ME/CFS mostly affects women and other marginalized folks, and disability issues in general are usually among the first to be compromised under fascism. Fighting against both the stigmas attached to ME/CFS—such as laziness, “work shy,” attention seeking, and hysteria—and its instrumentalization by right-wing conspiracy theorists for their anti-vax agenda makes our struggle one that’s anticapitalist, feminist, and antifascist. Indeed, at both of our demos, we faced small batches of (sometimes violent) counterprotesters, clearly from Far Right circles.

So we grieve daily. For the loss of physical strength and participation in life. For when another person dies from ignorance in a hospital. For when a friend “chooses” assisted suicide because the reality of their life makes them feel as if they’re already buried. And we will continue to hold rituals for as long as our illnesses—ME/CFS and other chronic conditions—are neglected by a heartless capitalist “health care” system, fascistic power holders, and maybe saddest of all, so-called leftist spaces.

—Tea “Kára” Drobniewski

8

I wish I wrote down instances of joy more, but I’m not gonna force it. I have a deep desire to write about the love notes on my altar, lavender greeting me at the farm, calendula overwhelming me, my friend drawing snails to remind me to go slow, the sweetness yet tang of lemon balm tea in my mouth, kisses and pets of cats, even if they make my eyes itch.

Yet here’s the thing. I know that maybe people are tired of hearing brown queer trans folks in grief, but damn, the burdens keep getting heavier to hold. So when I come to these pages, I must rage. The page swallows my words like a pill.

Last week, Israel bombed many neighborhoods I remember in Tehran; one place was six kilometers away from my house, the place I lived in my youth.

I tried to sandwich my instagram stories with:

[690 Iranians detained by ICE last week]

a picture of saffron and pomegranate

[More than 900 Iranians (hamvatani) killed by Israeli forces]

a picture of two Iranian men dancing sweetly together

[60,000+ Gazans killed by Israel, 66 times the number in Iran during war, I explain to the Iranian uncles, hoping they will also care about Palestine and see our fights as interconnected]

a picture of olive branches and poppies

Here’s the info—horrible, real. Let me humanize us for your consumption. Add a spoonful of my flesh and blood, a tear, and something funny. But writing is a medicine for remembering; for continuing to be alive.

—Yasi Shaker

9

I have never wanted to believe in God more than I do now

I have never wanted more than now

for there to be a hell

where the unjust go

and the righteous are spared

When I meet him I will ask,

“What have you done?”

I imagine he will ask the same of me

We will weep

because the answer is the same

Not enough.

—Mark K. Tilsen

10

Some years ago I adopted four parakeets who had escaped the pet trade but were unable to survive alone outside. They live with me indoors, uncaged. Being with them, seeing how we do together, has metamorphosed my awareness of belonging and reciprocity. The love I feel for them so overwhelms, it makes my heart physically ache. They are my Kropotkin swans.

“Old woman, I hold in my hand a bird. Tell me whether it is living or dead?” is the question posed in a Toni Morrison story by some children to an old, blind town outcast. Long ago, this story helped me deal with what felt like a dead world, before I was old and had lost my gaze, before my body understood dissent as a line of flight.

A video circulated recently showing a girl, maybe ten, kneeling, face contorted in anguish, holding the stiff body of a tiny green parakeet. The text pasted over it said: “Selma lost her bird due to the intensity of the bombing near their house.” I saved a still. Each time I look, the heart goes rabid. No matter what I ever thought the question of the bird may have meant (for Morrison, it was the survivability of a language the state can’t capture), Selma holds its answer. I am annihilated.

I pray she is still alive. Across dimensions, time, and space, together we re-form: Selma, me, and this pain.

—A. Hornak

11

Every few days, I get up, go to my laptop, print out a couple-dozen posters from the many curated folders of art sourced from Flyers for Falastin, carefully stuff all the prints into a transparent plastic folder with a snap fastener, top up my water bottle with wallpaper paste, give it a good shake for half a minute, wrap the bottle in an old tartan-print tea towel that’s hardened in some areas, and shove the whole thing in an old IKEA ziplock bag along with a half-used packet of wallpaper powder, pair of needle-nose pliers in case the bottle cover gets stuck, a wall brush about five inches wide with bristles that have gone a little stiff from hasty cleaning, put on my usual attire—a black, short-sleeve coverall and black sneakers—leave my flat quietly so the cat doesn’t wake up my partner, head down the labyrinth of corridors and flights of steps, rush through the humdrum of traffic, past the sea of faceless humanity, to the disused parking lot above the old market marked for demolition. Here, the real ritual takes place: with furious strokes and sloshes of gloop over brightly colored paper on pillars, walls, and any empty space left to fend for itself, I pour out my grief.

—shi Blank

12

This I know: not all grief is the same; varied losses have differ-ent textures. But nothing prepared me for grief under fascism.

Intellectually, I know that past fascisms have stolen so much from millions+, and the profound losses reverberate over generations. One can catalog lost kin and places, lost cultures, lost radical movements, lost possibilities. One can read books, visit genocide museums and mass murder sites, pause before monuments and public art of remembrance. One can be heartsick over the dead and sick over the human capacity for brutality when walking through a serene forest that, before erasure, was a centuries-old cemetery. I’ve done all of that and more.

Viscerally, that’s another matter. Our bodies seem poor containers to hold the immensity of losses swirling all around us. What can record, much less make sense of, the flood of sorrow that runs through one’s veins when living under fascism? So I try, and likely fail, to name my feelings, which first and foremost, is a lack of feeling. I know that I feel new emotions—like fear, paranoia, rage and impatience (mostly at liberals), indecisiveness (given what’s at stake), and lack of futurity—along with old ones—such as ancestral trauma and a sense of abandonment. But mostly, I feel flat, distant, numb. How can grief over fascism shut down my emotional range?

So I try harder to notice when I do feel; it’s always in little real-life moments that don’t look away from the grief of fascism. To name one: it wasn’t listening to the public reading aloud—with solemn intention and dignity, for sixteen hours—of some of the many names of children murdered in Gaza that somatically hit home. It was standing behind a Palestinian kid, maybe age eight, sprawled on the ground, an open notebook before them, writing each and every name down in crayon.

—Cindy Barukh Milstein

13

All of us in Shabbes 24/7, a queer Jewish collective in Belgium, had been coping with conflicts within our families and friendship groups. We were wrestling with our identities and roles as Jews in ending the genocide in Gaza, and the grief that goes along with living in a time of mass death in our names. We needed a space dedicated to rerooting in care and our values.

So we wrote our own “Shabbat Ritual for Holding Grief and Joy.” Because in Judaism, grief and joy go hand in hand; both need to be experienced fully and cannot be bypassed.

The first one we hosted was in a garden. We shared figs from the tree of one of our grandmother’s who was in the process of transitioning out of life. We named our losses and listened. We lit candles, sang, and reflected on questions we’d devised, and took a bite of something sweet. We read words we’d crafted to move us through our ritual—some of which are here; all of which we posted on social media for others to use:

“In memory, in defiance, in tenderness—against genocide, empire, and erasure. … [We] call in [our] ancestors—the broken, the brave, the exiled, the excommunicated. [We] call in the future, not yet born. … We do not mourn alone. We mourn across borders, beyond flags, into memory that holds us accountable and makes us whole. … [We] bless the defiant joy that still survives in [us]. … The world we want is not built on the bones of martyrs. It is built with their dreams, their unfinished songs, their whispered hopes. Grief and sweetness can live in the same breath.”

We arrived feeling a heaviness and left feeling lighter, having been able to shift a bit of our sadness, powerlessness, and frustration into togetherness, joy, and renewed focus.

—Fenya and Shoshana

14

The river is scarred with luxury condos and PFAS. A neighbor who lives under a bridge got violently evicted. A trans suicide attempt shake us. ICE abducted the neighbors before we arrived. The flock camera documents our movements. Safety is elusive. We feel the state closing in on our bodies. Trying to force us inward.

Yet we find soft landings: bergamot bitters, windswept sand, the call of the crane. We remind one another of paths beyond decimation, through post-op care plans, river trips, and crip kinship. We dance and dream despite the wreckage. Life force weaves through the grief.

-Lior

15

Almost every week, for twenty-two months, we‘ve been marching for Gaza en masse—our cup of grief full. Yet even as the organizing became tighter and the speeches more on point, the media coverage evaporated. The police tightened their lines, vacuum sealing our mobilizations. Large numbers of people in one place seemed to have less and less impact. Meanwhile, our sorrow only increased as the atrocities multiplied. Our cup spilled over, time and again, with seemingly nowhere to go.

But like charged ions, our energy, catalyzed by our grief, diffuses across the barrier. Small numbers of people grip Palestinian flags and gather on new corners. Neighbors hold bake sales, fly kites, paint murals, hold vigils, and gather. Some, until now silent, join in. Grief has dispersed us across the landscape and drawn us onto the lesser-traveled streets, touching people and places that hold the heaviness of these times.

—Lesley Wood

16

“We just bombed Iran.”

We were in our swimsuits. We were leaving the beach, returning to the concrete and traffic lights. The conversation halted as we swiped and typed. Where did it hit? How many were hurt? How many were killed?

“This reminds me of October 7,” our friend said. “We were terrified for our family over there, trying to figure out where they were. It was stressful.”

After some time on their phone, they spat, “People are being dismissive as fuck in this chat. I’m leaving it. Why are people like this?”

Cynicism protects us. It puts distance between ourselves and the situation. “The United States has always been an imperialist state. What did we expect?” “I knew this would happen. How could anybody be surprised?”

But reacting with cynicism also puts distance between us and the people who are affected, and the people who are feeling it deeply. We want to be disconnected from tragedy, but instead we disconnect from those around us. To move through this, we need to be together. And being together means being vulnerable and lingering in our grief.

As we continue through this nightmare, let’s invite ourselves out of cynicism and the detachment it provides. Let’s hold our knee-jerk “I knew” and “of course” to ourselves for a moment, and watch what can happen when we find words that connect us to each another’s pain, shock, and fear. As fascism and its brutality intensifies, let us be human in the face of it together.

—Astaroth

17

The planned destruction of Gaza City is an unthinkable atrocity on the tip of history’s tongue. We do not yet know if it will be spit out like wormwood or swallowed with gusto. ICE’s destruction of our communities and sowing of fear is like a blanket of night on the land, as centuries of settler society reaches even more lethal conclusions. It’s becoming harder and harder for queer and trans beloveds, and even harder to believe in the possibility that “we will outlive” the state’s repression.

I feel all of this and more straining my heart, threatening to squeeze tears from my eyes to the point of bursting. I grieve for lost beloveds. I grieve for what’s being torn apart and occupied, for martyrs and rebels slandered as “outside agitators” in their own homes. Every Shabbos, when I do my hormone injections and bring the light to my eyes, I worry I’m not strong enough to survive.

Through it all, though, I try and remember that grief is the flip side of love and a sign of what we’re capable of. To love and be loved is dangerous. We cannot comply in advance, no matter how much we’re told we’re wrong to love this much.

Oh Great Mystery, I call out your name from the depths of this pit: the way I love is not wrong. Make my outpouring of grief a mirror so that I never forget just how adept I am at love. Our capacity for loving connections is our capacity to withstand the horrors to come, to face our fears, to become subversive. To all of my lovers constricted by sorrow, I pray, “Let’s become dangerous, together.”

—Anastasia bat Lilith

18

Today marks one week since the encounter with the border patrol agent in the El Paso, Texas, airport. A racist white man saw me as a disposable person.

Today marks one week of not being able to see the sunsets every evening; of not being able to feel the warmth of the land; of not being able to sprout seeds; or hear the elders and children laugh. It has been a week full of stories of strife rooted in forced immigration and to come face-to-face with the criminalization of the immigrant. Getting to see the guts of the for-profit system that scrutinizes every move we make, that locks us far away from loved ones.

Where the lights are on day and night; where every evening’s dinner is a frozen ham and cheese sandwich, crackers, and orange juice; where you ask for permission to use the bathroom and bathe yourself at certain times of day.

Those who work here make fun of the immigrants in English. When people get sick, they make fun of them, and the nurses only offer them water. The water in here stinks.

But here we breathe companionship and solidarity. Here we share ailments, stories, advice, encouragements, and learn to play games together.

In the words of Roque Dalton, the Salvadoran poet: “My veins don’t end in me, but in the unanimous blood of those who struggle to live, love, little things, landscape and bread, the poetry of everyone.”

And how they say in the South: “The fight continues until dignity becomes the norm.”

—Cata “Xóchitl” Santiago

19

If grief means to make heavy, then we must ask ourselves, How will that weight be distributed? How do we take that weight and turn it into a blunt force object with which to bludgeon the fascist regime that would otherwise see us disappeared either by death or incarceration (a social death as it’s called)? Fascism capitalizes on our grief by immobilizing people with the looming threat of such fates. But we will not limit ourselves to its endings. As anarchists, we are much more creative than that.

When my partner was locked away as a result of our assault on fascism, we got creative with our lifelines. When communication was reduced to ghostly transmissions in the form of letters and phone visits, we found portals of possibility. He put strands of hair in a letter so I could put them on his pillow, remembering when our bed was shared. I drew raindrops on fingertips to hold against the plexiglass when I visited the prison, reminding him of the earth he could not see. Sacred doesn’t have to mean somber, so we tell jokes, sharing laughs with loved ones on both sides of the walls, thinning the veils. Defying the dictum, we choose life. With his continued incarceration, the weight of our grief has not lessened, but we don’t carry it alone.

As we grieve publicly, let us all rage against the dying of the light by being brave together and accepting that if our courage makes us outlaws, so be it.

—Krystal

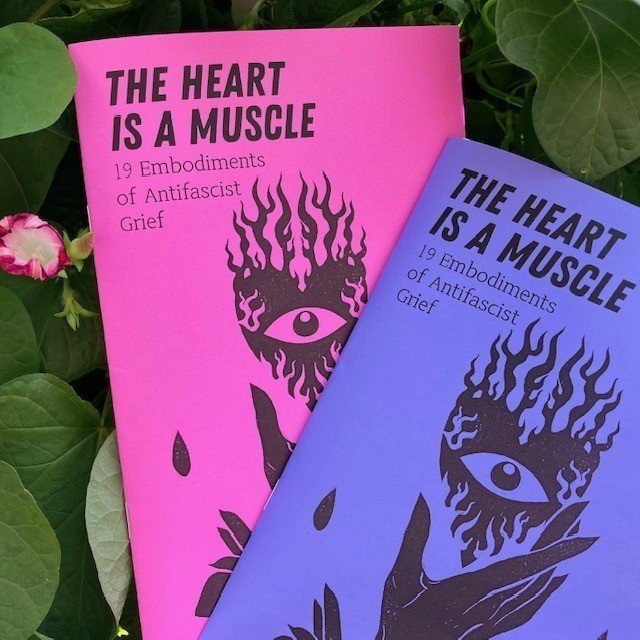

The Heart Is a Muscle: 19 Embodiments of Antifascist Grief is an act of love and solidarity. Please share this zine freely and widely.

For other zines in this series,” check out Don’t Just Do Nothing: 20 Things You Can Do to Counter Fascism and Anarchist Compass: 29 Offerings for Navigating Christofascism, and most recently, Ritual as Resistance: 18 Stories of Defending the Sacred,

For other zines in this series, see Don’t Just Do Nothing: 20 Things You Can Do to Counter Fascism, Anarchist Compass: 29 Offerings for Navigating Christofascism, Ritual as Resistance: 18 Stories of Defending the Sacred, and most recently, Everyday Antifascism: 14 Ways That Solidarity Keeps Us Safer, all freely available at ItsGoingDown.Org, with big thanks to IGD for hosting the texts and PDFs on its website.

I extend my gratitude to Ez Naive (EZNaive.com; @ez.naive.art on IG), a Greek artist currently living and creating on the traditional, unceded, and ancestral lands of the Coast Salish peoples, for the cover artwork, originally titled “Devotion,” and as with past zines, Casandra (www.houseofhands.net) for kindly turning my design and layout into PDFs.

August 2025

cover photo: Alissa Azar