Filed under: Incarceration, Midwest, Publication

Announcing the summer 2023 edition of The Opening Statement, from Michigan Abolition and Prisoners Solidarity (MAPS).

The Opening Statement is a free quarterly newsletter that features articles, poetry, political writing and opinion pieces, as well as other relevant pieces by non-incarcerated authors.

OPENING STATEMENT – SUMMER 2023 (CLICK THE LINK TO DOWNLOAD PDF)

ARTICLES AND AUTHORS LISTED BELOW:

- Lay of the Land: An Abolitionist Standpoint MAPS

- In the Shadow of the Shadow State Ruth Wilson Gilmore

- Michigan News Roundup, featuring three articles from the Detroit Free Press on MDOC’s policy of making people stand outside to get their medications

LAY OF THE LAND: AN ABOLITIONIST STANDPOINT | MAPS

Since the police murder of George Floyd in 2020 and the nationwide uprising it provoked, the discourse around abolition has shifted. When MAPS came into being in 2016, those of us committed to police and prison abolition were a passionate and smallish crowd, always excited to cross paths with likeminded people. Before 2020, most people had never heard of the contemporary abolition movement. Over the last three years, though, abolition has become a standard leftist position that has gotten the kind of mainstream media coverage we never could have imagined just a few years ago. We think it might be time to clarify again (or for the first time, for our newer readers) what MAPS stands for.

Don’t misunderstand that if you disagree with something here it means you’re outside our circle. We’re interested in stimulating dialogue about these ideas, not unanimity. Movements need to move, not stand still, and we need to hear each other’s voices to grow and light the path forward.

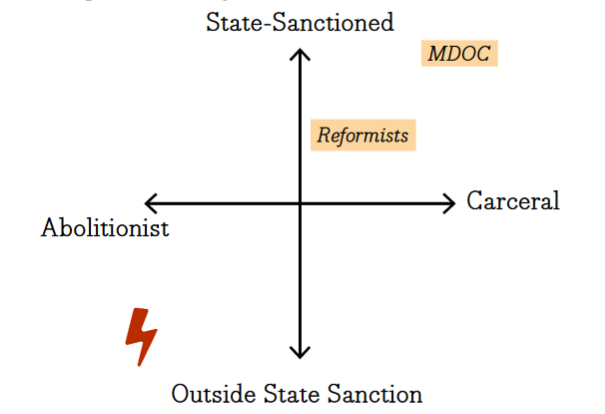

MAPS stands for Michigan Abolition and Prisoner Solidarity. What do we mean by abolition, and by prisoner solidarity? One way to map out what we do, and do not, represent is to take a look at other groups organizing around prisoner issues in Michigan. At one end of the spectrum are those committed to abolishing all forms of incarceration; at the other end are those committed to mass imprisonment, to caging and confining human beings.

Along another dimension, the MDOC and related agencies and politicians are the state itself. Other organizations are more or less state-sanctioned or work in cooperation with the state. A smaller number, including MAPS, intentionally remain outside the circle of entities which the state accepts and collaborates with.

If you’re a visual kind of person, you might imagine the landscape something like this:

See MDOC at the upper right corner? They are the epitome of state-sanctioned carcerality in our state. See the lightning bolt at the lower left corner? That’s MAPS! Abolitionist, against state control and outside of state structures.

Of course, this crude plot is an oversimplification. There are groups and individuals scattered across the landscape, groups might change strategy and practices over time and across contexts, and there are more dimensions than just an X and Y axis.

Still, we find it a helpful diagram because we’ve noticed a pattern in this state. A lot of the groups that do prison-related work cluster towards the upper center. That is, they tend to work towards reforming carceral systems to make them a little less unjust, incrementally less harmful. In the course of that work, they may be glad to work with state agencies and politicians, and vice versa. They might be pursuing state or federal funds to achieve their goals. There are diverse viewpoints between and within these groups, but for the sake of argument, let’s call them the reformists.

Here at MAPS, we believe it’s important to hold down that lower-left corner. Here are some reasons why.

Abolition, Reform, and Non-Reformist Reforms

Most people who are paying attention agree there are a multitude of problems with the carceral system, so we don’t need to argue that. For abolitionists, our political analysis diverges from that of the many groups seeking incremental reforms. For one thing, we don’t believe that mass incarceration is the problem. As abolitionist and Black studies scholar Dylan Rodríguez has argued, this term “reframes carceral domestic war in liberal reformist terms as a compendium of discrete, mistaken excesses of state power that largely derive from criminological error, electoral opportunism, and vague ‘moral’ failure.” We don’t think the prison population just needs to be reduced to a more acceptable size, so it will cost less or be more manageable or cause a little less harm. Instead, we believe putting people in cages is wrong and intolerable, period.

We also don’t believe that the criminal justice system is dysfunctional and needs to be made more just, fair, and smooth running. Instead, we see that the system is working just as intended—as a central pillar of racial capitalism. Racism and all other kinds of oppression in the system are not flaws, they are features. This system was and is designed to maintain neo-colonialism, class divisions, cisheteropatriarchy, and racism; keep Black and Brown and poor neighborhoods oppressed; and prop up the crumbling structures and contradictions of late-stage capitalism. Low-income disabled, neurodivergent, and LGBTQI2+ people are singled out for special hells in this carceral system, and that is also by design. These systems of oppression are historically interconnected, and can never be fully understood in isolation.

One predictable reaction to our argument goes like this: “But we need prisons, because they are the only way to deter and punish violent criminals. Mass murderers and pedophiles really should be in prison.” We get where it comes from, but we take a different view. When you step back and look at violence historically, both the science and the lived knowledge of the most impacted communities says the exact opposite. For one thing, the carceral system itself is a site of extreme violence of all kinds. In this sense, incarceration can only move violence, not solve it. For another, it increases violence across the spectrum of society—especially in poor and Black and Brown communities—by justifying police abuse, depriving families of their loved ones, and blocking people returning to the outside from accessing basic needs like housing, sustenance, healthcare, and respect. And of course, there are loads of mass murderers, rapists, and pedophiles running around freely as things stand, many of them politicians, priests, cops, bosses, and celebrities.

Arguments against abolition fall apart like this on closer examination. The purpose of this article isn’t to dismantle them all (which has been ably done by many others, including authors in other issues of The Opening Statement). Our purpose is to explain a little of what we stand for, and why.

Does being abolitionist mean we don’t support any reforms to policing, courts, or prisons? No. We definitely support moves that give those of you inside immediate relief from the horrific conditions of confinement in the MDOC, in particular. Over the years, MAPS has helped amplify concerns raised by folks inside about issues like atrocious food, inflated prices, low wages, sexual harassment and abuse, transphobia, retaliation, lack of healthcare, censorship, solitary confinement, pandemic conditions, and many more. So how is that any different from the reformists?

Before pushing for a reform, we try to consider a set of principles important to us as a group. First, we consider whether the changes proposed give more life to the carceral system, or chip away at it. For example, does the reform increase funding for MDOC that can be used to hire more staff, raise salaries, guinea-pig novel technologies, or build infrastructure? Then it’s giving more blood to a vampire. Or, does the reform undermine MDOC’s rationale for more staff, budgets, and buildings, thereby halting future growth and chipping away at the existing system? Does the reform further burden family members and communities with new fees and rules, or does it channel funds to community-based and community-owned resources? Does the reform buy into the state and mainstream media narrative that prisons “make society safe”? Or does it lay bare how prisons are the origin of spiraling violence? Does the reform make prisons work better and run smoother, or does it underscore how dysfunctional prisons are now and will always be? Does the reform promise freedom or early release for some prisoners, but only by reinforcing divisions between so-called “non-violent” and “violent” criminals? “Good” (“legal”) versus “bad” (“illegal”) immigrants?

You get the idea. If a reform helps to “shrink and starve” the carceral system, then it could be a reform that MAPS can get behind. Some organizers call these “non-reformist reforms,” because they serve a larger strategy that moves toward prison abolition, while simultaneously working to bring relief to folks inside. We might even collaborate with reformists on projects like these. Sometimes it can be to everybody’s advantage to engage in a broader terrain of struggle to address the same condition of confinement.

Unfortunately, groups that are not committed to abolition too often line up behind reforms that actually:

- expand funding to prisons (for example, in the name of increasing personnel, training, or programs)

- do not challenge the notion that prisons make us safe (and instead fall in line with tired tropes like “a well-functioning prison system keeps us all safer”)

- expand MDOC’s access to tools, tactics, and technology (for example, putting trackers on all inmates, and other e-carceration tactics that expand surveillance and shift even more costs of incarceration onto the incarcerated and their families)

- perpetuate the scope and scale of prisons (by promoting the building of new facilities, while failing to underscore the illegitimacy of institutions born out of racial capitalism and slavery)

- generally strive to make prisons run more smoothly, like a well-oiled death machine.

Those kinds of “reformist reforms” are regressive, effectively rationalizing and preserving the carceral system. Though they claim to help, and even if they do in fact help some individuals, they often make the general situation worse and further entrench the carceral regime.

Even when reformists take up a “non-reformist reform,” they seldom acknowledge that diverse strategies can be used in complementary ways. Historically, there has been a tendency for such groups to scoop or appropriate an issue that abolitionists or folks inside have brought to the public, and then water down or de-fang those strategies that directly challenge prisons and the state. Now that abolition has gained more currency, they may even intentionally confuse the issues to get more people on board with their reforms. This is co-optation and counterinsurgency.

To illustrate how these frictions play out, let’s take the example of gender violence, which includes intimate partner violence, rape, and sex trafficking. Reformists seldom see outside the box of carceral feminism. Carceral feminism refers to mainstream, mostly white feminists who co-opted movements against gender violence that emerged from earlier, more radical anti-racist movements. Thanks to carceral feminism, we see so-called “progressive” prosecutors who on the one hand make campaign promises to reduce mass incarceration, while on the other feel emboldened to hammer defendants accused of gender violence. Thanks to carceral feminism, we see legislation like the Violence Against Women Act (pushed by Biden in the early 1990s) which poured 85% of its billions of dollars into the carceral system. Moreover, VAWA initially required states to implement mandatory arrest policies at scenes of domestic violence in order to receive VAWA-based funding. Though this requirement has relaxed in the 30 years since VAWA passed, this piece of legislation still channels about $268 million into criminal legal responses to intimate partner violence. So after 30 years, rates of intimate partner violence have not even declined as much as crime rates overall. In other words, the massive investment in carcerality that VAWA represents did nothing to deter or decrease intimate partner violence, while it built systems that actually disempower and harm many survivors of gender violence.

For decades, groups like Incite! and others, often led by Black and Brown women, have been creating and advocating for non-carceral strategies that actually transform the roots of gender violence while better meeting the needs of survivors. The carceral system instead worsens those same root causes. MAPS stands in solidarity with those building viable alternatives to the harms of carceral feminism. [To learn more about alternatives to carceral feminism, see transformharm.org, or write to us and we’ll try to send you some articles.]

A second example of how these dynamics can play out is the attempted expansion of local jails in the name of mental health and substance use treatment. In Detroit, Toledo, Atlanta, and other cities across the country, cops and politicians have tried to appropriate hundreds of millions of dollars to build shiny new jails. They tell the public that the “services” would include “humane” treatment for people with mental health or substance use issues. Reformists may fall for these false and hypocritical narratives. But abolitionists, people with mental health and substance use issues, and their advocates step up to say no, not in our name. More than anyone, vulnerable people in crisis should not be locked up in cages where they are almost invariably subject to abuse, neglect, and death.

For a third example, look at the way children and youth are treated by the state. In April 2020—a month before cops murdered George Floyd while he cried out “I can’t breathe”—Cornelius Fredericks, a 16-year-old Black boy, cried “I can’t breathe” while his “caretakers” at a youth facility in Kalamazoo smothered him to death. His crime? Throwing a sandwich in the cafeteria. But the reason he was in the facility in the first place was for the “crime” of being a motherless Black boy and “ward of the state.” Under the interlocking systems of racial capitalism, cisheteropatriarchy, and the nation-state, Cornelius and other children like him are criminalized, incarcerated, and exterminated by the same state that works to protect the white, wealthy, nuclear, heteronormative family.

Just like the false narrative that restricting choke holds will keep cops from murdering people like they did George Floyd, the state and reformists called out for restrictions on the use of restraints in youth facilities. They began to question whether private, for-profit corporations could really be trusted to care for children—as if it was the for-profit status that was the problem. What they did not do was question why the state locks up and warehouses children. The children who lived at the facility with Cornelius protested his murder, and were themselves pepper sprayed.

We say fuck that shit. We say communities can do better, we can do better. We stand for abolition.

Now, it’s important to acknowledge that the categories we’re talking about are not always totally clear or self-evident. It’s not always easy to distinguish between non-reformist and reformist reforms or to understand how a specific proposal relates to abolition as a political horizon. Lines can be blurry, and there’s often no clear answer in the moment. Our analysis of a particular program can change as circumstances on the ground or political realities shift—or in dialogue with comrades inside and outside the prison walls. Abolition can feel very far away, and the steps to get there feel messy or unclear. We make the best decisions we know how and learn from experience, from putting our principles into practice.

Also, it’s not as if we all came out of the womb as perfect abolitionists, yelling “No more cages!” Each of us in MAPS came to abolition over time. As a group, we draw from many different political genealogies: Some of us came to abolition through learning about state repression against movements for Black liberation, and through supporting political prisoners and prisoners of war who were caught up during the heyday of COINTELPRO: Sundiata Acoli, Russell “Maroon” Shoatz, Mumia Abu-Jamal, Leonard Peltier, and Marilyn Buck. Some of us came to prison abolition after seeing the “War on Drugs” play out in cities like Detroit, Flint, and Benton Harbor; the “War on Terror” on Muslim, Arab, and Southeast Asian people in communities like Dearborn; and the war on poor children and parents waged in the foster and juvenile justice systems. Some of us have organized against police killings in Michigan and beyond, or have seen other social movements be crushed by police repression. Some of us have family and friends in prison, or have volunteered inside, solidifying our commitment to abolition. Some of us draw political lessons from the life and struggle for self-determination by the EZLN in Chiapas, Mexico, as well as other indigenous struggles for freedom in occupied Hawai’i, Samoa, the Philippines, Palestine, Canada, and the US. Some of us came to prison abolition through organizing against US deportation machines. Some of us came to abolition through organizing in support of anarchists and environmentalists targeted by the federal government in the Green Scare of the 2000s. Some of us used to ascribe to some of the reformist, carceral feminist ideas around intimate partner violence, until we learned about their material harms. Some of us were activated by the writing and theorizing of trans and queer prisoners like Michael Kimble, Marius Mason, Kuwasi Balagoon, Miss Major Griffin-Gracy, Stevie Wilson, and CeCe McDonald.

Prison and police abolition is obviously one of our most important principles at MAPS, but there are others that guide us. We want to share a few more with you because they also influence what projects and actions we take on, with whom we’ll collaborate, and how. For example, we at MAPS share commitments to:

- opposing and ending white supremacy, racism, and essentialist ideas about race;

- opposing and ending neo-colonial appropriation of lands, resources, and life;

- opposing and ending imperialist strategies around the world that destroy entire generations and lands;

- opposing and ending capitalism as a political-social-economic system that values profit over people;

- opposing and ending the nation-state borders that wreck families and prop up all of the above;

- opposing and ending heteropatriarchy and transphobia, and bioessentialist ideas about gender and sex;

- access to healthcare for all, including full reproductive rights;

- supporting freedom for Palestine, and self-determination for all peoples;

- a transformative justice response to interpersonal harm, including gender and intimate partner violence.

This is not an exhaustive list, just a few of the common threads that we at MAPS can trust with each other, and that we can’t always trust with members of some other groups. As we said at the beginning, though, we don’t have to agree entirely with everyone we work with. If you disagree with us on one of these important principles, we can still dialogue and maybe even collaborate. More on that in the next section. But we admit that we are unlikely as a group to compromise these core principles.

Prisoner Solidarity

The second part of our name is “Prisoner Solidarity.” By solidarity, we mean that we as a people have more that unites us than divides us. The histories of oppression that different groups experience are critically important to understand. At the same time, standing together against our particular as well as our common oppressors, we can go much farther than we can divided.

By prisoner solidarity, we mean that we are in common cause with imprisoned people striving for freedom. We seek to communicate across the barriers imposed by the MDOC and to build relationships of mutual respect, collaboration, and accountability inside, outside, and between the two. Accountability means we do not excuse or sanction anyone causing ongoing harm to others, inside or outside, and we also strive to never treat anyone as merely expendable. Prisoner solidarity can be blurry and messy sometimes too. For example, a person in prison might reach out to us asking for something that conflicts with our principles and commitments, like those we mentioned above. We might have to say no, we won’t do that. In some cases, we might be able to offer an alternative, or suggest another organization.

On the other hand, most of us in MAPS (at this time) have not been locked in prison, and can’t know the lived experience of that. We need and want to learn and grow from and with those of you inside and outside the artificial walls between us. We work with an openness to people growing, changing, learning, and developing or sharpening a political analysis maybe they didn’t have before—including us at MAPS. After all, that’s kind of what The Opening Statement is all about. Mutual political education. Prisoner solidarity.

Some groups have a similar philosophy to ours. For example, Oakland Abolition and Solidarity has as one of their 11 points of unity: “We offer critical support, not servitude. We retain our own principles, judgment, and decision-making power. This is mutual political development. We are comrades in a struggle that grows and evolves on both sides of the wall.” But some reformists set themselves in an entirely different relationship to imprisoned people. They may endorse a narrative of rehabilitation that we think is patronizing, infantilizing, and in many instances harmful to imprisoned people. They may also reinforce a brand of respectability politics that labels “good” or “model” prisoners at the expense of “bad” or “disruptive” ones.

Respectability politics have many and profound implications. Some groups make formerly imprisoned people stand up and tell a story of rehabilitation with undertones of religious redemption—how they used to do bad things, then struggled with their demons, and now (usually thanks to the group) they’re ready to fly straight and give back. Basically, the same story the Parole Board expects to hear. But the narratives and the groups that demand them are incredibly patronizing (like the Parole Board), and leave the majority of people outside the circle of care and solidarity. Maybe most importantly, they reinforce the myth that imprisoned people are the ones mainly responsible for causing harm—not the countless power brokers who materially profit off of other peoples’ suffering, while exactly no one expects them to be held accountable.

For a more subtle example, reformists often work in the mode of “humanizing prisoners in the eyes of the public” and calling for “humane treatment.” On the surface of it, who would argue with that? But what this discourse obscures is that a society that cages more people than ever before in the history of the planet, as a direct consequence of racial capitalism, slavery, and genocide, is itself sick and inhuman. This system and its perpetrators and jailers are the ones who need to regain their humanity—by abolishing prisons—not the people who are encaged. Who gets to decide who is human and who is not? To treat people “humanely” is to treat them “as if human.” This is just a sleight of hand that slyly tries to keep in question whether imprisoned people are actually human or not. We seek to abolish this question, along with the prisons.

For a more concrete example, when over 200 people were sent to the hole in the wake of the incident at Kinross in 2016, very few reformist groups were interested in connecting with them or speaking out publicly against the state’s abusive retaliatory actions. To those groups, it didn’t seem to matter that the majority denied involvement and all had been subjected to varied and unnecessary suffering; they still didn’t want to be remotely associated with the incident. At MAPS, by contrast, we didn’t mind if some or all of the people were involved. We understood that the root motivations behind the incident were just, and that the state’s violent retaliatory actions were wrong no matter what. We stood in solidarity with imprisoned people in material ways, and spoke out publicly against MDOC’s retaliatory actions. We believe this made a difference, both to those impacted inside and to public perceptions.

Why were so few groups willing to stand up against one of MDOC’s most obvious incidents of repression? It wasn’t only because of kneejerk respectability politics—that is, that only certain, well-behaved, cooperative imprisoned people deserve support. They were also afraid.

Some groups conduct their advocacy for imprisoned people by working directly with MDOC staff and state legislators. They have a “seat at the table” that they believe gives them the best opportunity to make change. They are state sanctioned, in the language of our diagram above. Speaking out publicly against the MDOC could lose them that coveted seat. That could lose them not only the influence they believe they have, but also their main strategy and reason for existing as a group.

There are material reasons for them to be afraid too. Many reformist groups are incorporated non-profit organizations. This allows them to receive tax-deductible donations and makes them eligible for many other funding streams, such as grants from foundations, corporations, or local, state, and federal agencies. They depend on these grantors for their salaries, operating budgets, office rent, and to keep their lights and phones turned on.

Once committed to this model, and dependent on these grantors, non-profit groups may find themselves compromised when it comes to addressing certain issues, or speaking publicly in certain ways, that might offend their more conservative grantors. The Non-Profit Industrial Complex (NPIC)—an allusion to the Military Industrial Complex and the Prison Industrial Complex—suffers from this basic dilemma across all social justice issues. The NPIC depends so heavily on grantors that some groups tend to perpetuate, not solve, the problems they rely on for their existence and careers. We’ve included an article by Ruth Wilson Gilmore, “In the Shadow of the Shadow State,” in this issue of The Opening Statement for more on the history of the NPIC.

MAPS prefers not to have a seat at the table because we would rather publicly confront the state and MDOC than privately work with them. We prefer not to be a non-profit because we would rather call our own shots about how to be in solidarity with imprisoned people, instead of being hamstrung by the fear of losing grants. We don’t want that to be even a remote consideration for us. We also don’t want to spend half our time applying for those grants. We prefer not to have staff or salaries, which can lead to such entanglements. Instead, we all donate our time. Our capabilities are those that we and our local, regional, and national networks can provide. We’ve got skills, but not all skills! For example, we currently have no capability to provide legal help.

We believe there can be complementarity in many cases, when groups with different kinds of resources and capacities work together towards common goals, even if those goals are limited or contingent. For example, we know when to suggest other groups that might be better able to meet someone’s particular need.

Obviously, there are advantages and disadvantages to any organizational model. Who wouldn’t want to have the kind of financial resources that many non-profits have? But in our minds, there’s no question that the advantages of holding down the lower left corner of the map far outweigh any disadvantages. We have the flexibility and freedom to respond to needs from an abolitionist standpoint. We do abolition, not reform.

Michigan Abolition. Prisoner Solidarity. There you have it.