Filed under: Analysis, Indigenous, Quebec

Praised on both sides of the white world as a turning point in the way of dealing with indigenous communities, a crucial “modern treaty” is getting ready to be signed, should all go poorly. The Petapan Treaty with the Innu communities of Mashteuiatsh, Essipit, and Nutashkuan is the result of 30 years of negotiations, during which six other Innu and Atikamekw communities have ended up withdrawing from the process, leaving a handful of Band Council chiefs to rule on the future of a territory 16 times larger than the Island of Montréal.

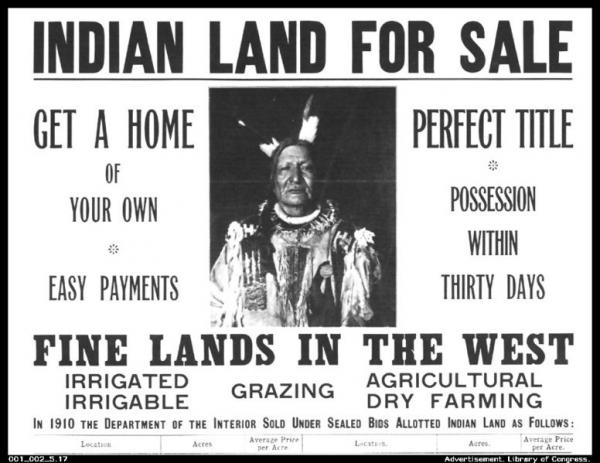

Expected to be signed around the end of next March in the National Assembly, the Petapan Treaty claims to recognize “autonomy of governance” of the territory of Innu Assi, supposedly putting an end to the long history of encroachments upon indigenous peoples, and their cultural assimilation and extermination. If this brutal history was certainly conducted by means of treaties, the last on the list would be, they say, of a different kind. Unlike the James Bay Agreement, which allowed for the constitutional integration of not less than 20% of the “Québécois” territory – around 300,000 km² – from the hands of the Cree, the Petapan Treaty does not intend to “extinguish” ancestral rights, but only to “harmonize” them with those of Québec…

Encompassing the watersheds of Lac Saint-Jean, a large part of Labrador, and all of the Côte-Nord, Nitassinan – traditional territory of the Innu and the Atikamekw – extends over close to 100,000 km². This is where animals and fish have found refuge from the reach of civilization – two thirds of Nitassinan are zoned as beaver reserves – and where minerals and powerful rivers have not yet been harnessed. This is what makes this treaty crucially important for a government that never ceases to want to finish off the natural resources.

Beyond these altruistic outward appearances, the Petapan Treaty hides a considerable problem behind this facade. To be sure, the Innu will become the “managers” of their territory – not all Innu, obviously all of this only concerns the duly authorized Band Council chiefs. Managers… This is the term that the government used to designate families who have a certain territory for hunting, up until it was replaced by “area wardens” to avoid any confusion. But if the development projects will have to receive the approval of the Innu people, and if they will not doubt be granted the traditional “vacation pay” of 3% of income, this transfer of territorial management towards the ancestral “owners” does nothing except to force their hand to open it up to infrastructural development. See the trick: at the end of a period of 12 years, the federal government will cease to pay insurance benefits that today it owes to reserves, leaving to the semi-autonomous government, not to say Innu protectorate, the job of raising its own taxes.

Without more assistance from the federal government – compensations for the atrocities it committed – the Innu will have to resolve to open their resources to exploitation, or otherwise simply starve. Especially since the costs already undertaken for the negotiations, what with the huge number of field studies and legal opinions, are up to more than 40 millions dollars… Not counting that the government of Québec had already reserved total and exclusive ownership of water and underground resources, as well as 75% of surface minerals. If it had to change its mind faced with protests, finally leaving the Innu to reign alone over their resources, the territory of Innu Assi that would have been realized by the agreement was then cut by more than half, going from 2,538 km2 to 1,250 km2. In Nutushkuan, a 50-megawatt hydroelectric dam project is already feverishly waiting for the conclusion of the agreement – the 2004 agreement, which is to be the basis for the treaty, takes it for granted, maintaining that “Québec will commit to giving priority to the First Nation of Nutashkuan on the development of hydro power of 50 MW or less in Innu Assi.” Given the dislocation and scattering of Innu Assi’s project territory, one can understand well why it took 30 years to identify and remove all zones of strong geological potential from the agreement.

The resistance

But there is absolutely never anything so easy. Sometimes it is enough for a small rumbling of opposition to ruin a rip-off that’s been years in the making. A number of Innu “area wardens” are currently rising up against the Petapan Treaty, and starting to make waves. In presenting themselves at random selection hearings for the “managers of trapping territories” before forming the “Tshitassinu committee” in order to benevolently advise on the application of the treaty, these opponents are starting discussions that quickly put the entirety of the process back into question. Multiple blockades of roads and forest trails, to which have been added members of Atikamekw communities, simply ignored by the agreement, is putting a non-negligible pressure on a process whose validation relies upon an appearance of ethical purity.

If the opposition to the Petapan Treaty clearly sees right through the game of government, it’s because they have their own established way of life. As far as the eons-old practice of hunting, trapping, and fishing is concerned, the treaty does nothing less than to render this form of life extinct, through the Québécois and Canadian systems of permits, certificates, catch recording, hunting seasons, and game quotas (point 5.7 of the agreement). It is therefore the mode of life the most suitable to indigenous people before colonization – hunting and fishing as the principal means of survival – which finds itself attacked in one of its last holdouts on the continent. There, where one can find the last wild animals able to provide for the needs of a limited population of hunter-gatherers, the covetousness of mine and hydro intends to destroy that which the settler colonies have devastated everywhere else. However, the relationship of treaty-opposing Innu traditionalists to the ancestral practice of the hunt is considered “sacred”. In other words, it cannot be harmonized with white norms without it losing its soul. The hunt, as intended in its full sense, as an inalienable spiritual activity, contains an immemorial relation to the Innu territory, and a knowledge of how to live there more sustainably than with any development. As a occupier-hunter of the Innu territory recounted: Our ancestors have lived on this territory since long before the creation of the Band Councils by the Europeans. They have given us the necessary knowledge to live and do things for millenia in Nitassinan. We don’t need a treaty or a government to control or restrict our traditional practices. The long walk of the Innu has never needed European laws on Nitassinan!

It is thus apparent that this re-emergent indigenous sovereigntism in so-called Québec isn’t the one that speaks in Band Councils and reads agreements. The groups of Innu and Atikamekw hunters contrast real, de facto independence to the legal, de jure independence of the Petapan Treaty, denounced as an incursion of the European concept of the State. So do not hesitate to respond to their call for solidarity if they act to support this indigenous affirmation of an ancestral independence. In recognizing, first of all, how the structures put into action by treaty negotiation are entirely attributable to whites – let’s remember that more 50% of the Essipit Band Council employees are whites coming from Escoumins and other contiguous municipalities; the resistance to their insidious maneuvers is thus as much the responsibility of non-indigenous solidarity as of the concerned communities. Next, in taking seriously the conceptions of the world and of the specific territories of these communities, as the incarnation of a real face of a continued resistance to the civilization of development, at the same time as their privileged target. Which brings us to ask ourselves, concretely, how to recognize their de facto independence, and how to assist their rejection of resource extraction projects. Because this Turtle Island where we are staying contains a number of ferociously sovereign ways of living, which demand to be considered as such. Even if that means dissolving what they have customarily considered as Québec and Canada.

Let’s support the struggle against the Petapan Treaty!

For more information, visit the Facebook page of Regroupement des familles traditionnelles de chasseurs-cueilleurs Ilnuatsh.