Filed under: Anti-fascist, Quebec, White Supremacy

An in-depth look at the fascist group Atalante from Montreal Antifascists.

Raphaël Lévesque, the public face of the neofascist group Atalante, really likes the attention his little stunts get him (that’s why he has long since stopped hiding his identity). However, the central role of a single individual should not prevent us from looking at the people who gravitate to his leadership, because a movement like Atalante is nothing without the militants that give it life.

All the actions that the group has carried out in Québec City and Montréal over the past two years to increase its visibility suggest that, along with its more visible members, Atalante can count on a reserve of a few dozen individuals who support the ultranationalist cause. Despite its small numbers, the group has caught the eye of a section of the mainstream media and has made effective use of social media to promote a so-called “national revolutionary” position within Québec’s far right.

The practice of masking up in public clearly indicates that the majority of Atalante’s militants want to hide their association with this openly fascist group. We think it is high time to shine a light on the militants and sympathizers of Atalante.

We also think it’s important to clear up any confusion about Atalante’s political project and to expose the group’s direct ties with different fascist currents.

Insignificant Actions and Free Publicity…

Despite its marginal nature, Atalante managed to make headlines several times in 2017 and 2018, particularly last May, when a handful of its militants burst into the Montréal offices of VICE with the specific intent of intimidating the staff on site that day. The report published a few days later described the incident thusly:

When an employee opened the door for a man holding bouquet of flowers, a group of six or seven men, all masked except one, burst into the main room with the theme music from the The Price Is Right playing on a small Bluetooth speaker. The men then moved on to the newsroom, where they threw around clown noses and hundreds of leaflets . . .

The specifically attempted to intimidate the journalist Simon Coutu—who has written about the group—by gathering in his office to give him a trophy sporting the inscription: “VICE: Média poubelle 2018.”

Raphaël Lévesque, aka Raf Stomper, said the visit was to thank Coutu in the name of “all of the victims of the war you are trying to start.”

In response to this dreary bit of political theatre, Atalante was mentioned in media all over Canada, in the United States, and even in Europe. Beyond that, the action was denounced by Premier Philippe Couillard and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. On a propaganda level, Atalante pulled off a neat little coup with only six people and a limited amount of imagination.[i]

As will become clear, this is Atalante’s modus operandi: putting a minimum of energy into these little propaganda actions that gain a lot of media coverage and create a platform for spreading its ideas, accompanied by the use of Facebook to project an image of strength.

Atalante’s Grimacing Public Face

As the only member of the group who had not covered his face, Atalante’s main man, Raphaël “Raf Stomper” Lévesque, faces a variety of charges for the action against VICE, including break and enter, mischief, criminal harassment, and intimidation. This is just the sort of judicial overkill that is more likely to increase his stature (and boost his already substantial ego) than to achieve anything else.

The thirty-five-year-old Lévesque (born August 5, 1983) is well-known to Québec’s antifascists. He has previously been indicted for assault, uttering threats, and drug trafficking, and was in prison as recently as 2016. In 2017, he called for the torching of the offices of the “Centre de prévention de la radicalisation menant à la violence” should the latter act on its stated intention to set up in Québec City. Although the center’s director Mr. Deparice-Okomba said that this constituted a criminal threat, no legal action seems to have been taken in the matter.

Besides his run-ins with the law, Lévesque is the singer for Légitime Violence, an oï[ii] band that is part of the Rock Against Communism movement[iii], and a known leader of the Québec City Stomper Crew, a bonehead gang[iv] active for a number of years in the Québec City region and known for its ties to organized crime and drug trafficking.

The Québec City Stomper Crew, Rock Against Communism, and Légitime Violence

To understand the nature of Atalante today, it is useful to remember that the group grew out of the band Légitime Violence and the bonehead scene around the Québec City Stomper Crew (which is still the heart of the organization).

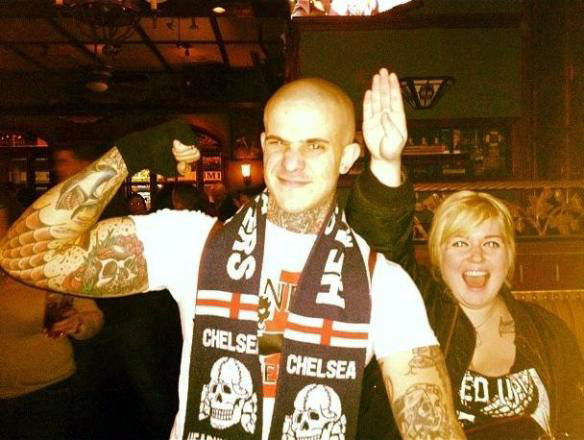

In the early 2000s, two so-called “apolitical” skinhead youth gangs emerged in the province. They were Coup de Masse (CdM) in Montréal and the Québec City Stompers (2004). Although they claimed to be apolitical, both gangs were strong supporters of Québec nationalism, which led to them being pushed out of the underground scenes in their respective cities. Even if the two gangs, which had very close ties, rejected both the left and the right (there are even stories about battles between the Québec City Stompers and the neo-Nazis in the Sainte-Foy Krew in the late 2000s), the Stompers rapidly gravitated to the bonehead milieu, adopting a so-called “anti-antifascist” position. At that point, the Québec City Stompers were Raphaël Lévesque, Yan Barras, and Martin Léger, with the addition over time of Benjamin Bastien, Antoine Mailhot-Bruneau, Yannick Vézina, Olivier Gadoury, Jonathan Payeur, and Roxanne Baron. Even today, there seems to be a distinction between the memberships of Atalante and the Québec City Stompers —the latter being more narrowly focused and countercultural. While all of the current members of the Québec City Stompers are members of Atalante, the inverse is not the case.

A recent photo of Québec Stompers: Étienne Mailhot-Bruneau, Olivier Gadoury, Raphaël Lévesque, Sven Côté, Antoine Mailhot-Bruneau, Jonathan Payeur, Benjamin Bastien and Yan Barras. See more pictures of the Québec Stompers here.

Both of these gangs were enthusiastic aficionados of a musical scene made up of Rock Against Communism (RAC) and Rock Identitaire Français (RIF), two musical styles that are a direct outgrowth of the far-right scene. In Québec, the major bands are Coup de Masse, Section de Guerre, Fleurdelix et les Affreux Gaulois, and Bootprint, joined by Légitime Violence in the late 2000s. A group that could be seen as a major influence on this scene is Trouble Makers, largely associated with RIF. The RIF style is an attempt to package far-right ideas in a slicker and more mainstream musical style than is typical of RAC. Formed in the late 1990s, the members of Trouble Makers are Simon Cadieux, Maxime Taverna, Jonathan Stack, and François-Pierre Stack, the latter three being longstanding identitarian militants, known, among other things, to have been members of different far-right groups, including Québec-Radical and the Affranchistes. Trouble Makers were also the first Québec band to cross the Atlantic to participate in events organized by CasaPound in Italy.

Early in the 2010s, after numerous attempts to form a far-right collective in Montréal, including Troisième Voie Québec, Légion Nationale, and the Faction Nationaliste, Maxime Taverna founded the neofascist groupuscule La Bannière Noire, which eventually became the Montréal chapter of the Fédération des Québécois de Souche (FQS), a precursor to Atalante. With a membership that included Rémi Chabot, Mathieu Bergeron, François-Pierre Stack, and Francis Hamelin, we can already discern the core of what would eventually become Atalante Montréal. Even if rarely active, the collective took on the task of uniting the far-right bonehead scene by organizing identitarian networking soirées and hosting the radio show La bouche de nos canons, broadcast by Bandiera Nera, a chain connected to Zentropa, a far-right media network with ties to CasaPound. Bannière Noire was the first right-wing collective in Québec to openly develop a relationship with the Italian far right and to use imagery similar to what would later be used by Atalante. It is beyond question that the group and its founder Maxime Taverna have played an important role in the creation of Atalante and continue to hold a place as leading ideologues.[v]

A History of Violence

Many former and current members of the nebulous bonehead scene that has existed since the 1990s have taken part in violent attacks, particularly against racialized people.

In 1997, eight associates of the Vinland Hammer Skins and Berzerker Boot Boys were accused of a series of attacks with baseball bats and metal bars, injuring around thirty people in bars around the city. Among them, Jonathan Côté, alias “Jo Wennebago” (Chevrotine Jo on Facebook), remains very close to the Stompers. Steve Lavallée (Steve Bateman on Facebook) was a central figure among neo-Nazis back in the day, particularly as a member of the band Coup de Masse and allegedly as a leader of a short-lived Québec section of Blood & Honour. Today, Lavallée seems to have toned it down, but he still hangs out with the boys from Légitime Violence and Atalante.

On June 22, 2002, Rémi Chabot and Daniel Laverdière gratuitously attacked and stabbed a Haitian worker, Evens Marseille, outside a bar in the Montréal’s East End. Rémi Chabot remains part of the nebulous neo-Nazi scene of which Atalante is the current standard-bearer.

On New Year’s Eve 2007, six of the Stompers, including Raphaël Lévesque, burst in to the Bar-Coop l’AgitéE, a left-wing hangout in Québec City, and one of them, Yan Barras, stabbed six people with an X-Acto knife. Légitime Violence makes reference to this brutal attack in their eponymous song: “Ces petits gauchistes efféminés, qui se permettent de nous critiquer, ils n’oseront jamais nous affronter, on va tous les poignarder!” [These little leftist sissies, who dare to criticize us, wouldn’t have the nerve to face us, we’d just stab them all!][vi]

In 2008, Mathieu Bergeron and an accomplice, Julien-Alexandre Leclerc, were arrested for knifing two Arab youths and attacking a Haitian taxi driver. Bergeron would remain a key figure in the Montréal neo-Nazi scene for a number of years, as a member of the StrikeForce crew, singer for the RAC band Section St-Laurent, and founder of Faction Nationaliste. Today, Bergeron is part of the Atalante inner circle and has participated in many of the group’s actions. Francis Hamelin, another Montréal associate of Atalante, is a longtime friend of Mathieu Bergeron.

Légitime Violence’s Fortunes and Misfortunes

Légitime Violence songs overflow with racism and homophobia (one of them, an Evil Skins cover, has this notable pro-Shoah passage: “Déroulons les barbelés, préparons le Zyklon B!” [Roll out the barbed wire, get the Zyklon B ready!][vii] Before the founding of Atalante in 2016 the band’s influence outside the bonehead scene was fairly limited.

Information about Légitime Violence concerts in Québec City is generally shared in a very controlled word-of-mouth way to avoid reprisals from antifascist groups. They have achieved greater success in Europe, where the band have been able to tour and sell promotional material.

Légitime Violence: Raphaël Lévesque, Jean Mecteau, Benjamin Bastien & Jean-Seb (missing, Félix Latraverse).

In 2011, the group took a hit, when, responding to public pressure, the Envol et macadam festival in Québec City pulled its concert from the program.

In 2013, the band toured Europe, creating ties with other neo-Nazi bands, and for the first time staking out clear political positions. Two years later, a second tour led members of the group to found a neofascist group on the model of CasaPound (Italy), Hogar Social and Bastion Social (France). The result was Atalante, which was officially founded in 2016.

Légitime Violence also maintains close ties with the RAC and bonehead scene in New York, specifically with the (now defunct) band Offensive Weapon and the label United Riot, which distributed a split recording featuring the two groups in 2013. They also have connections to the 211 Bootboys Crew, a New York City bonehead crew, some of whose members have been found guilty of armed assault and others who currently face charges for beating antifascists outside a recent talk by Proud Boys founder Gavin McInnes at the Metropolitan Republican Club in Manhattan.

As recently as November 2018, members of Légitime Violence went to France to pay their respects to the late Sergei Ventura, a bonehead piece of shit who had been part of Serge Ayoub and Troisième Voie’s entourage.

The group Troisième Voie before its dissolution. In the middle, Sergei Ventura with Serge Ayoub. Between them is Estaban Morillo, who murdered Clément Méric.

Romain, formerly of Troisième Voie, with Raphaël Lévesque, in the Fall of 2018. Note the Skrewdriver t-shirt .

Défends, the Légitime Violence album that came out in 2017, is intended as a sort of self-referential homage . . . to Atalante.

Atalante’s Ideological Affiliation

Buoyed by propaganda and street action, Atalante hopes to contribute to an “identitarian renaissance.” The description the group provides of itself on its Facebook page —which has six thousand subscribers— reflects the “declinist” perspective that characterizes a significant segment of the contemporary far right:

In this sombre age, as globalization and consumerism reign, we are being suffocated by the tyranny of political correctness and the negation of our identity. The West is being undermined from within by the collapse of traditional values and principles.

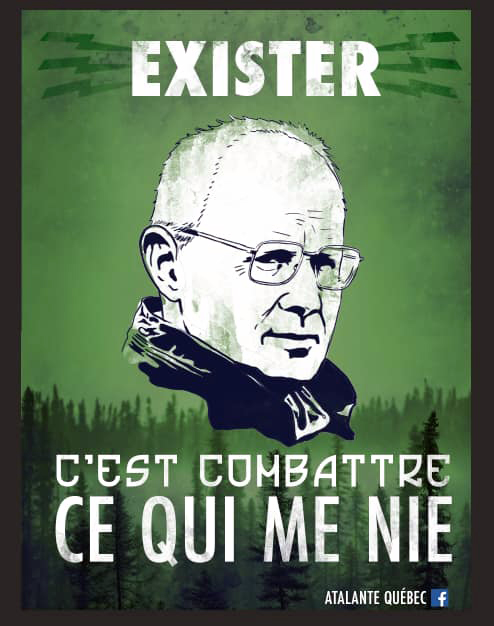

Atalante’s slogan, “to exist is to fight against that which negates my existence” is borrowed from Dominique Venner, a mythic figure on the French far right. Initially a member of the Organisation Armée Secrète (OAS), a far-right paramilitary group that fought against Algerian independence, later he was a historian who advanced the “clash of civilizations” thesis. Venner committed suicide in 2013 at Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris to protest against same-sex marriage.

Atalante is aggressively ultranationalist, identifying with the culture and history of the French Canadian nation, or as Atalante members put it, New France.[viii] The name Atalante refers to the French frigate the Atalante, which ran aground during a battle with the British in 1760. The group’s logo is a ship’s wheel with a lightning bolt cutting through it.

Indeed, Atalante’s worldview draws heavily on the history of Quebec (or French Canada) as an oppressed, conquered, nation. Understanding this history primarily through a cultural and demographic lens, Atalante holds that French Canadians have been subjected to an attempted genocide for centuries. This narrative draws on specific elements of Quebec history, and in the past, for instance in the 1960s, a similar logic led many people to develop a left-wing nationalism that identified with and supported Third World anticolonial movements. In 2018, however, this approach most easily finds its logical extension in far right conspiracy theories about “white genocide”, the “grand remplacement”, or the “Kalergi Plan”, all of which are in fact reference points for Quebec far rightists (including Atalante) today. The fact that the overwhelming majority of Québécois reject this kind of extreme racism is explained away as a result of “degeneracy” and “brainwashing.” This version of Quebec history has been summed up by Antoine Mailhot-Bruneau in an interview with a far-right website in 2017:

(…) the turning point of the creation of this fake nation [Canada] came when the new way to destroy us was introduced – immigration, that came from the ‘report on the affairs of british north America’ made by Lord Durham in 1839, who recommended that the French had to vanish. This happened before Canada became a county [sic] in 1967; the year 2017 is special because they are celebrating the 150th anniversary of this fraud. First they failed their objectives, because they brought Irish Catholics, Italian Catholics, Greek Catholics, Polish Catholics and many other Catholic Europeans; all those foreigners actually adopted our culture and made us even more European and quite unique. After this failed attempt, they realized they had to bring an entirely opposite culture of strangers to mix with us, or to make us an even smaller minority in Canada. So to mask their plan and make it look more attractive for the leftist ‘nationalists’ and other retarded liberals and Marxists, they decided to bring in immigrants that spoke French, such as Haitians and North Africans. The worst part of their plan is that they actually damaged british culture in Canada more than ours – for example, if you visit a city like Toronto it is worse there than in Montréal. However, we now take in more immigrants than France – imagine our future! All of these immigration politics are a plan to exterminate our people.”

Atalante describes itself as “national revolutionary” organisation[ix]. As one militant put it during an interview with the Breizh.info website:

The use of the word revolutionary shocks a lot of people, but it reflects the fact that we don’t want to retain anything from the decadent and sick modern world. What we want to do is create the warrior aristocracy of tomorrow by encouraging our militants to practice intense sports like extreme fighting and weight training and to read all sorts of literature.

We don’t want to preserve this hierarchy, with the wealthiest at the top and the poorest at the bottom, but want to establish a meritocracy that advocates the foundational Western values. By foundational values, we don’t mean the decadent world of the recent past, but the timeless values of heroism, adventure, a sense of sacrifice, honor, and a taste for risk-taking (there are many others, too).

The members of Atalante are primarily inspired by CasaPound, an Italian neofascist movement from which it borrows both elements of discourse (rhetoric that connects anti-immigrant sentiment with anti-capitalism, etc.) and mobilizing tactics (charity initiatives exclusively for “old stock” citizens, etc.).

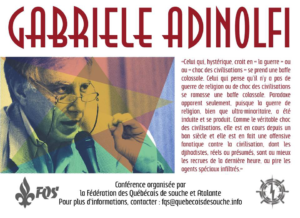

In August 2016, in collaboration with the Fédération des Québécois de souche, Atalante organized a seminar in Québec City by Gabriele Adinolfi, a pioneering intellectual of the Italian Third Position movement and a supporter of CasaPound. Then in 2017, members of Atalante, including Antoine and Étienne Mailhot-Bruneau, went to Rome for a get-together with fascist militants from CasaPound and the affiliated Blocco Studentesco.

Promotional poster for a Gabriele Adinolfi conference organized by Atalante and the Fédération des Québécois de souche, in August 2016.

Jean-Sébastien, Raphaël, and Benjamin of Légitime Violence, with Sébastien De Boëldieu and Gianluca Iannone, respectively the international spokesperson and National President of CasaPound.

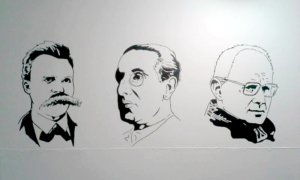

Atalante doesn’t try to hide its admiration for fascist intellectuals. Next to a portrait of Dominique Venner that is painted on the wall of its gym is one of Julius Evola, a figure recognized by many as the most important thinker of the fascist renaissance of the second half of the twentieth century. In March 2018, Atalante posted a homage to the “martyr” François Duprat, a national-revolutionary theorist and major defender of historic fascism, on its Facebook page.

Portraits of Friedrich Nietzsche, Julius Evola, and Dominique Venner on the wall of Atalante’s Québec City gym.

As a national-revolutionary group, Atalante co-opts anti-capitalist themes, notably opposition to the international bourgeoisie (embodied in their rhetoric by the spectre of “globalism” and the mythic Georges Soros),[x] claiming that they are carrying out a war against the white working class by introducing “a cheap foreign workforce” that will undermine the gains of “old stock Québécois.”

Paradoxically, although the national revolutionaries, who detest communists and anarchists in a visceral way, up to wishing for their deaths, aren’t satisfied with just co-opting elements of left-wing theory but also frequently adopt tried and true tactics of the anti-capitalist left. The intervention at the VICE offices, for example, is a style of action picked up from Atalante’s sister organizations in Europe, which those organizations have stolen from the toolbox of the far left they so mortally hate. The same is true of the distribution of clothing and food to impoverished (“old stock”) citizens, which is a central Atalante activity in Québec City and Montréal. Then, of course, there are the banner drops, another proven far-left tactic. One might even think that the contemporary far right is incapable of an original thought. . .

The cosmetic shifts in the identitarian far-right scenes on both sides of the Atlantic (European “identitarians” and the alt-right in the U.S.), including the gradual fine-tuning of their images, with the transformation of brutal and scary neo-Nazi boneheads into clean-cut and disciplined nipsters. As Antoine Mailhot-Bruneau has explained, they “realized that if we wanted more people to join, we had to be more casual and more accessible for people.” This face-lift therefore shows a desire to be perceived more positively and eventually accepted by moderate nationalists, to begin with, and then by ever larger sections of society, with the hope that their particular brand of profoundly racist identitarian ultranationalism, based on a cult of violence, will take root in the population at large.

The Curious Cohabitation with the National-Populists

Atalante’s positions have sometimes led them to adopt a critical posture vis-à-vis other far-right tendencies, particularly the current national-populist movement. For example, although Atalante members showed up at the March 4, 2017, Islamophobic demo in Québec City, they stayed in the background, and in a leaflet later posted on Facebook lamented the fixation of the populist groups on Islam, seeing the true enemies as multiculturalism, “mass immigration,” and the “bankster” system.

Similarly, and in keeping with “Third Position” politics, the banner they deployed that day bore a modified Karl Marx reference: “Immigration: Armée de réserve du Capital” [Immigration: Reserve Army of Capital]. (In a similar vein, in 2017, Atalante members distributed pamphlets outside a book launch of the conservative and Islamophobic columnist Mathieu Bock-Côté, criticizing him and others on the right who do not take a more radical anti-systemic stand.)

This perspective was further elaborated by Antoine Mailhot-Bruneau in the aforementioned interview:

There are some groups such as the Soldiers of Odin, and an internet group called the Meute – these groups focus on stopping the islamization of Canada while defending democracy, but this is not our way at all. We are indeed against non-European immigration, but more importantly we are against a regime that uses immigration to exterminate us. This regime uses third world immigrants for their industries, putting pressure on the local workers and we cannot defend something that is not defendable like democracy. We believe that democracy is the worst regime the world has ever known, a regime built and lead by the bourgeoisie that have only served the establishment and their interests.”

That said, 2017–2018 was marked by a certain rapprochement between the Islamophobic and anti-immigrant national-populist milieu and the small neofascist current to which Atalante belongs. This occurred incrementally as members of these different groups began “liking” the same racist ideas on social media, became “friends,” and took part in the same demonstrations —in some cases ending up side by side in tense standoffs with antifascists— the neofascists starting to get encouraging feedback from reformist and non-aligned right wingers.

The most visible and tangible example of this occurred on November 25, 2017, in Québec City, when members of Atalante and the Soldiers of Odin came down from their position at a distance on the ramparts of the esplanade to join a La Meute and Storm Alliance demonstration “in support of the RCMP” (!) outside the Quebec National Assembly. Members of these latter two groups enthusiastically applauded the fascists and welcomed them with open arms. (Shortly after this surprising convergence, made possible by the repressive actions of the Québec City police against antiracists, two well-known neo-Nazis in Montréal, Shawn Beauvais-MacDonald and Philippe Gendron, the latter a member of the Soldiers of Odin, tried to form a “Montréal chapter” of Atalante.)

Nonetheless, this wasn’t the first time that Atalante members participated in a demonstration of the broader far right alongside national-populists. In a December 2016 VICE article, before Dave Tregget left the Soldiers of Odin to create the Storm Alliance, we find him on the telephone with Raphaël Lévesque, making sure that Atalante members will be coming out for an SoO anti-immigration demonstration. Katy Latulippe, the president of Soldiers of Odin Québec, has also publicly spoken of her great respect for Atalante, adding that the two groups had carried out joint patrols in Québec City (in essence, acts of intimidation directed at immigrants).

An Atalante and Soldiers of Odin demonstration in Québec City, on April 1, 2018, to commemorate the centenary of the draft riots in Québec.

Recall that Katy Latulippe replaced Dave Tregget at the head of Soldiers of Odin Québec in early 2017; she later reiterated her admiration for Atalante:

“We are united on many issues,” the president of the Québec chapter of the Soldiers of Odin, Katy Latulippe, said about Atalante. “There is a great deal of mutual respect between the two groups. They distribute food in the streets and so do we. Why not have the pleasure of helping each other out? We have good chemistry together. Our homeless and out veterans are dying of hunger in the streets. How can you take in people from other countries, when you aren’t capable of taking care of your own people?”

Close Ties Between Atalante and the Fédération des Québécois de Souche

While the ties to the Soldiers of Odin are not insignificant, the Fédération des Québécois de souche is a more important ideological influence on Atalante. The FQS was created in 2007 by Maxime Fiset as an explicitly white supremacist organization (Fiset is now a repentant former Nazi who has patched himself over into a so-called expert on the far right). The FQS magazine Le Harfang was one of the first francophone publications to promote elements of the Alt-Right, and its editors, who use the collective pseudonym “Rémi Tremblay,” have often collaborated with alt-right publications in the U.S. The FQS’s mission could be described as attempting to unite the diverse far-right tendencies in Québec, from traditional Catholicism to the identitarians, while reducing the gap between the generation that was active in the 1980s and the contemporary militant far right.

It is quite likely intercession by the FQS that enabled Atalante to organize public prayer on the Plains of Abraham on May 1, 2016, with a priest from the Fraternité sacerdotale Saint-Pie X (FSSPX)[xi], a traditionalist far-right Catholic organization. The connection with traditionalist Catholicism arose again in May 2017, when Atalante took responsibility for security at a conference in Montréal organized by the Association des parents catholiques du Québec, another far-right organization, with Marion Sigault (an Alain Soral sympathizer) and Jean-Claude Dupuis (from the above-mentioned FSSPX, and previously a member of Cercle Jeune nation).[xii]

A mass officiated by a priest from the Fraternité sacerdotale Saint-Pie X, on May 1, 2016, in Québec City, organized by members of Atalante and the Fédération des Québécois de souche.

Poster announcing a conference with Jean-Claude Dupuis, a close associate of the Fraternité sacerdotale Saint-Pie X, at which Atalante supposedly provided security

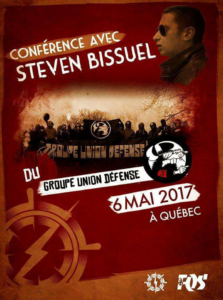

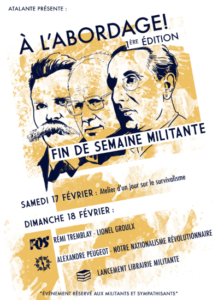

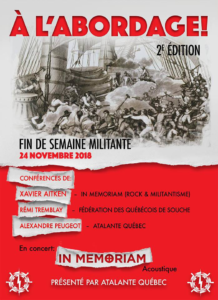

In May 2017, the FQS and Atalante joined forces to organize the visit of a militant from the Groupe Union Défense (GUD), a far-right French student organization and an immediate precursor to Bastion Social. In both February and November 2018, as part of its “militant weekends” reserved for “members and sympathizers,” Atalante turned the microphone over to a “Rémi Tremblay” from the FQS…

Paper Tigers (and Banners)

As mentioned above, Atalante’s public activity basically consists of distributing lunches to (“old stock”) homeless people, paying symbolic homage to various intellectual “heroes” (Jeanne d’Arc, Dominique Venner, the French navigator Jean Vauquelin, etc.), and putting up paper banners with political slogans in quick and furtive nighttime actions.

A look at the slogans on their banners should suffice to provide a clear idea of their politics: “REMIGRATION,” “IMMIGRATION: RESERVE ARMY OF CAPITAL,” “SOCIAL JUSTICE: PRIORITIZE THE NATION,” “TERRORISTS OUT: ISLAM OUT,” “WESTERN SAMURAI” (!), etc.

On one of their public outings in Montréal, in August 2017, Atalante members put up banners demanding “remigration,” particularly around the Olympic Stadium, where Haitian refugees were being temporarily housed.

Atalante views Muslims and racialized people as the swelling ranks of invaders and terrorists who must be expelled. In the face of what they describe as “our quiet extermination,” in the style of far-right European groups like Génération Identitaire, Atalante calls for “a reverse in the flow of migration and a far-reaching remigration accompanied by an effective policy to increase the birth rate.”

“Remigration,” a term that has come into vogue for identitarian movements on both sides of the Atlantic in recent years, essentially designates a programme of ethnic cleansing.

Atalante members have visited Montréal a number of times to sticker, poster, and hang banners. They have received the help of members of their anemic “Montréal chapter,” including Vincent Cyr and Shawn Beauvais-MacDonald (the former anglophone La Meute member who became a local neo-Nazi celebrity following his trip to Charlottesville in August 2017 and his active participation in the “Montreal Storm” neo-Nazi chat rooms under the pseudonym “FriendlyFash”). As we said previously, the increase in these rapid and risk-free incursions has permitted Atalante to achieve a certain visibility in the mass media and on social media.

In January 2018, they put up large banners in Montréal denouncing a series of people associated with the left (broadly speaking) and the antiracist movement in the city. Those who were white were denounced as “traitors,” while people of colour were classified as “parasites.” (Shawn Beauvais-MacDonald, Véronique Stewart, David Leblanc, and Martin Minna were identified as having participated in the action, thanks to the latter’s ineptitude.)

Shawn Beauvais-MacDonald, Véronique Stewart, David Leblanc and Martin Minna, following a banner-hanging action in Montreal, January 2018.

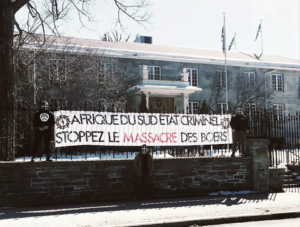

In August 2018, during another postering run, Atalante took up the conspiracy theory in vogue in white supremacist circles that the white farmers in South Africa are the victims of a “genocide” at the hands of the country’s black majority. This conspiracy theory has, in fact, been completely debunked, which hasn’t prevented members of Atalante (including Beauvais-MacDonald, yep, him again) from going to the South African embassy in Ottawa to unfurl a ridiculous banner denouncing the “massacre of Boers.”

Atalante banner unfurled at the office of the High Commissioner for South Africa, in Ottawa, March 2018. On the left, Shawn Beauvais-MacDonald.

In August 2018, Atalante militants in Montréal attacked passersby who objected to the content of the stickers they were posting, uttering threats and screaming at a woman to “go back to your own country.”

In September 2018, during the provincial election, Atalante put up posters on the electoral offices of candidates from the four main parties, denouncing the election as a farce. On its Facebook page, Atalante said it carried out this action because there is “no major difference between the parties’ programmes, other than a lot of nonsense. No inspiring national project capable of serving the common good.” Once again a very minor action that would have been ignored by the media had the left done it got Atalante headlines. As Antoine Mailhot-Bruneau has said regarding the media reaction to these stunts, “with all the people writing to us and encouraging us, journalists are really doing a good job of creating publicity.”

Although these minor actions in Montréal got some attention, the group is much more active in Québec City, where members gather regularly as a scene and wander the streets distributing bag lunches, pose in masks adorned with the fleur-de-lis (a practice copied directly from CasaPound), or clean up graffiti judged to be anti-national, later publishing photo albums of their exploits on Facebook.

Among the notable Atalante actions in Québec City was the creation of an “identitarian fight club” (opened, it would seem, in June 2017) named La Phalange, which serves simultaneously as a social space and a training centre for far-right militants.

It should be noted that the private events organized by Atalante appear to be opportunities to train its militants to carry out nighttime postering campaigns. Last February, Radio-Canada reported that the “militant weekend” mentioned above was held at Domaine Maizerets in Québec City, a publicly funded institution:

The event prospectus specifies a workshop on suvivalism and a conference with spokespeople from the Fédération des Québécois de souche and another national-revolutionary group.

The group’s masked militants took advantage of this gathering to stick up large banners all over Québec City during the night that read “Québec City, Nationalist Stronghold.” Photos of these banners were posted on Facebook.

In Conclusion: Vigilance and Organization Is What We Need

Atalante’s relative success is doubtless the result of a complex variety of factors, including the current resurgence of the identitarian right, the effective use of social media to reintroduce certain people and tendencies, and the media’s taste for sensational accounts of bad boys and sordid tales. Nonetheless, the radical left shouldn’t overlook certain tactical elements adopted by Atalante that reflect a genuine political acuity: a small group of dedicated militants can carry out simple targeted actions that spark the imagination and have an impact.

We need to understand that Atalante aspires to develop a coherent and revolutionary theoretical framework, which is not the case with the right-wing national-populist groups like La Meute. To the degree that they effectively establish and adhere to such a theoretical framework, the militants of Atalante will be better positioned than the national-populists and even than some of their liberal critics. Their repugnant ideology will necessarily limit the organization’s recruiting potential, but an eventual crisis could provide the group with an opportunity to effectively intervene and become a genuine movement. The worst-case scenario would be a fascist group occupying the political space that should be seized by the revolutionary left.

Let’s not wait until Atalante becomes as important and influential as groups like CasaPound or Generation Identity to organize to block its expansion. Let’s mobilize now to expose and deconstruct its political project and replace it with a social project that is revolutionary, anti-capitalist, egalitarian, and radically antiracist.

Let’s not lose sight of the fact that even in the absence of a crisis situation on which to capitalize, Atalante represents a genuine threat to that sector of the population that is directly targeted by its discourse, as well as to the comrades organizing in areas where it has a presence. Furthermore, a group like Atalante, as we have frequently repeated, constitutes a sort of pole of attraction offering a reference point and gateway for members of the larger national-populist right.

Consequently, it’s necessary to take Atalante seriously, even if the group only numbers a few dozen members whose activity consists largely of putting up banners and cleaning up graffiti.

We can’t encourage our readers enough to take seriously remaining informed and to share information with local antifascist collectives, or form collectives where there are none.

It is only if we are more numerous and better organized than the fascists that we can hope to block their way.

No pasarán!

///

Notes:

[iA] View a photo gallery here.

[i] Atalante militants previously used the same theatrics to intimidate a reporter from CBC News and Ian Bussières from the Soleil. For more information, see “Atalante et le harcèlement des médias.” They also engaged in a certain amount of tweaksome shit directed at La Presse journalist Philippe Tesceira-Lessard, who has published a series of articles about Légitime Violence, bringing to light the criminal histories of our little friends, and on active members of the Canadian Armed Forces among their symathizers.

[ii] Oï is a punk rock subgenre that was initially meant to draw different British working-class subcultures into a unified movement, but which was later hijacked by racist elements in the scene, with the goal of recruiting disillusioned proletarian youth into fascist political movements like the National Front and the British National Party.

[iii] RAC, or “Rock Against Communism,” is a neofascist movement created in the 1980s in reaction to “Rock Against Racism,” a movement formed by left-wing artists and musicians to combat the infiltration of racist elements into the countercultural scene, particularly the skinhead scene. The flagship RAC group is Skrewdriver, with its spiritual leader Ian Stuart, the group’s singer and the founder of the white power federation Blood & Honour.

[iv] The term “boneheads” designates racist and white supremacist skinheads, as opposed to the generic term “skinhead,” which designates members of the traditional skinhead counterculture, which, historically, was an inclusive and antiracist scene.

[v] For more information, see Xavier Camus, “Québec et l’extrême droite italienne.”

[vi] The eponymous song, Légitime Violence , 2010.

[vii] “Un amour perdu,” from the album Nouvelle France Skinhead, 2011.

[viii] The tattoos and inscriptions reading NFSH favoured by Légitime Violence and its fans signify “Nouvelle France Skinhead,” which is also the title of Légitime Violence’s first album, released in 2011.

[ix] The « nationaliste révolutionnaire » tendency is a branch of Third Position fascism. National-revolutionary and Third Position ideology are part of a political tendency that has existed since at least the 1960s, with many points of reference in the fascist movement stretching back to the “Strasserite” tendency in the Nazi Party. The term “Third Position” designates different far-right and neofascist currents characterized by the simultaneous rejection of capitalism and communism and favours an identitarian ultranationalism based on a confused mix of far-left (socialist) and far-right (nationalist) theories. Internationally, the Third Position is currently the dominant tendency within the fascist and revolutionary far right. The anticapitalism of most national revolutionaries is located in an antisemitic framework.

[x] The term “globalist,” like the recurrent references to the the secret hand of George Soros, is generally recognized as euphemistic code for the alleged international Jewish conspiracy, which is itself an echo of various nineteenth-century antisemitic conspiracy theories.

[xi] A leading opponent of the Vatican II reforms, Mgr Marcel Lefebvre founded the Fraternité Saint-Pie-X (FSSPX) in 1970 and established a seminary in the Swiss village of Écône. In 1975, Lefebvre received a Vatican order to dissolve the society, which he ignored. In 1988, in spite of a specific ban pronounced by Pope John Paul II, he consecrated four bishops, authorizing them to carry out the FSSPX’s work, which led to his immediate excommunication and the excommunication of the bishops who participated in the ceremony. Lefebvre, who died three years later, consistently refused to recognize his excommunication.

Lefebvre was suported by far-right movements the world over, including Blas Piñar’s Fuerza Nueva, in Spain, the Movimiento sociale italiano, and the Front national, in France. He regularly expressed vitriolic racism, striking out at Jews and Muslims, and was a fierce opponent of the ecumenical dialogue with other traditions advanced by the pope. In Québec, the Lefebvrists claimed the government was controlled by communists.

The FSSPX welcomes with open arms Catholics who oppose multiculturalism, democracy, and freedom of conscience and is outraged that the Church has abandoned its struggle against these various scourges. As Lefebvre put it: “[T]he union that liberal Catholics want between the Church and revolution is an adulterous union! Such an adulterous union can only produce bastards. . . .It’s the same with the Free Masons. . . . You don’t engage in dialogue with communists. . . . We cannot accept such a dialogue! You don’t engage in a dialogue with the devil.”

In Québec, the FSSPX has served as a spiritual refuge for the far right since the 1980s, when a number of members of the Cercle Jeune nation were active within the sect.

[xii] Dupuis was included in a recent news report by Radio-Canada on the Sainte-Famille private school, which is run by the FSSPX.run by the FSSPX.