Filed under: Analysis, US, White Supremacy

From Recomposition

We live in a time of challenges that can seem so great that they lead many to despair. Climate change, global instability, rising misery and inequity, racism and misogyny are on the march; the barrage of dangers is a heavy load to carry. Today’s article comes from S Nicholas Nappalos and takes us back to an even darker time, slavery-era America, where small groups of radicals defied the odds and dealt the ruling class a blow that has resonated through our history ever since. The defeat of 19th century chattel slavery in the United States stands out as one of the greatest victories for the American left. This may not be obvious especially in light the despicable condition of blacks today in this country. Likewise the rise and integration of the subsequent counter revolution that has become normalized can obscure the scale of victory against capital. The distorted official narrative of the anti-slavery Republican Party freeing the slaves out of mere moral conviction adds to the confusion. The role of radicals is even lesser known.

If we back up a bit away from the Civil War things become clearer. The abolition movement was always a minority within society as a whole and likely a quite small one. The majority of anti-slavery forces always supported gradual transition and reform with significant accommodations for Slave holders. Prior to the Civil War the pro-slavery factions were defeating the efforts to reign them in again and again. They won repeated battles to expand slave states, held one of the most conservative Supreme Courts in US history, enforced slavery through forcibly returning escaped slaves not only in the South but also in so-called free states, and were able to convince and mobilize workers in across the country to fight struggles of blacks as an attack against their own.

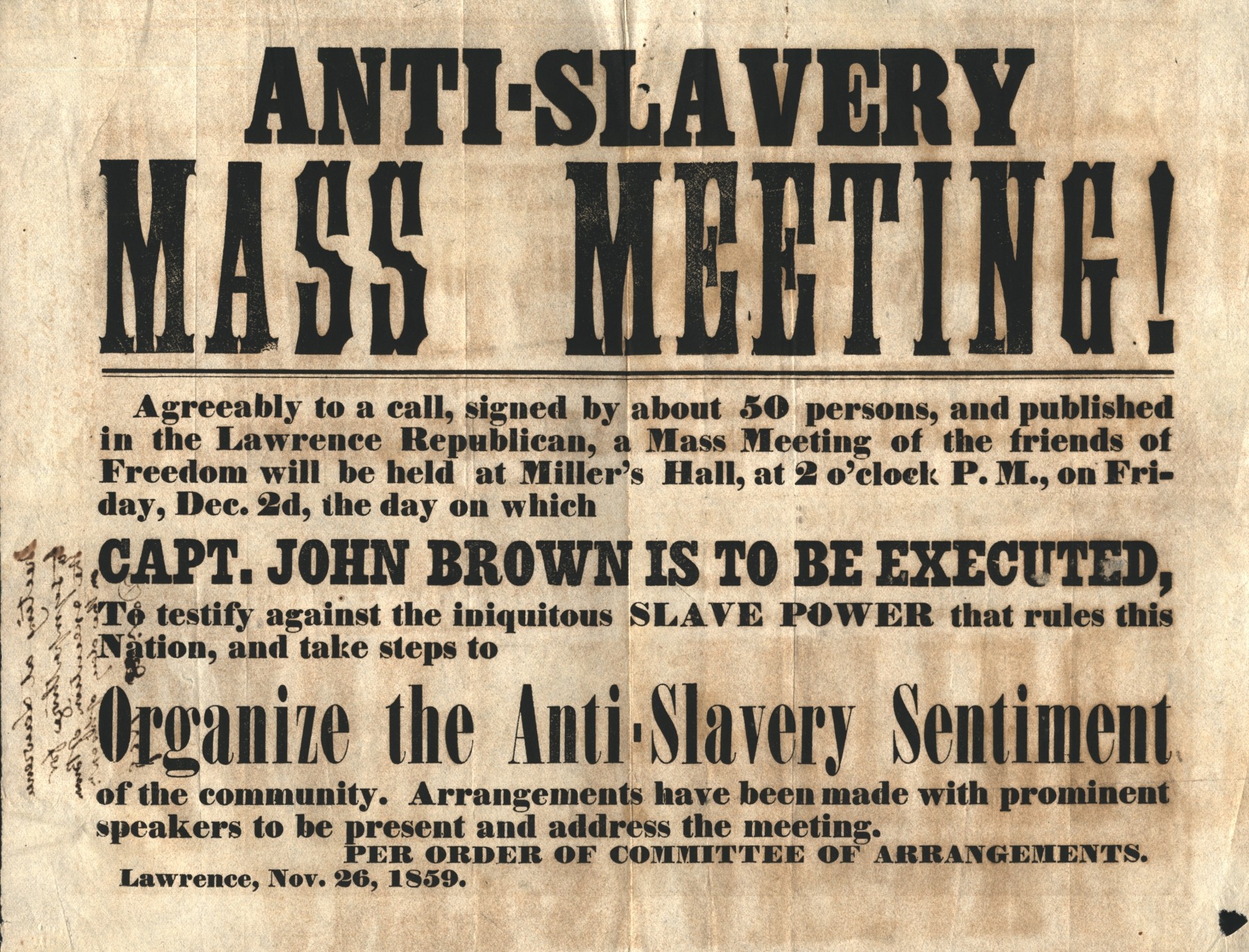

The radical abolitionists were thus a small if not tiny minority within a country that largely supported slavery and even openly hostile to blacks in general, slavery or no. The movement became more defined in the 1830s in response to the set backs and splintering of the gradualist movement to restrain and slowly eliminate slavery. By the 1850s the movement has suffered significant defeats with a seemingly unstoppable South and the potential of expansion of slavery into new territories on the horizon. It is hard to imagine how despondent they must have felt on the cusp of a shocking victory of historic proportions that they were soon to play a key role in.The radical abolitionists sought immediate unconditional abolition and condemned not only slavery but the entire system it was based upon: capital, church, and state. They were condemned and attacked at their rallies and yet they did not cow tow to the politics of their day. At protests they tore up the constitution, burned flags, and condemned the government and churches that gave their support to any compromise with slavery. Their vision was such that they supported the rights of women and workers alongside the struggle against slavery. Clashing with slavery opened up their militants to questioning ruling power in general in ways that must have been shocking to their contemporaries. Despite being a small minority they engaged in perpetual direct action and even armed conflict in Kansas, to prevent the expansion of slavery states, and supporting or initiating insurrections in the South such as that of the raid on Harpers Ferry.

The abolitionists likewise were more middle class, white (though it’s multi-racial composition was key), and geographically isolated in the NE compared to their cause. The movement was built however on the interaction between the slave resistance, escaped slaves, and radicals in northern cities through a process of dialogue and shared struggle. The resistance of slaves and abolitionists were linked with different roles and powers, evolved in together, and intervening at different moments that sustained each other. Ultimately it was the revolutionary action of the slaves that was the actualizing force as WEB Dubois’ seminal 1935 Black Reconstruction in America demonstrated, but at key points abolitionists had crucial roles to play that would shatter the ruling class compacts that held slavery together.[1]

The abolitionists took illegal direct action against power, and in doing so were able to destroy the political parties of their day, bring sections of the ruling class to their knees, and helped force the country as a whole into a war that would produce oppositional forces of liberation.

In destabilizing ruling order, abolitionists were a key power in creating the space into which the revolutionary slaves asserted themselves. Revolutionary slaves were able to outmaneuver both sides and began to assert themselves as a collective revolutionary subject and fought for regionalized social organization up through reconstruction.[2] Though ultimately defeated by an alliance of counterrevolution in the South and the Northern ruling class, the radically democratic nature of ex-slave societies has provided a model that continues through this day in American politics. The wave of crises and labor insurrections that followed were a direct response to the fracturing of power created by the revolution led by slaves. Protagonists both of abolition and the upheavals of the civil war would in some instances carry over to the socialist and anarchist movements of the following decades including the US 1st International sections, the anarchist IWMA and allied anarchosyndicalist unions, and the labor movement more generally.[3]

It is worth noting that recent studies have shown slavery was far more profitable than comparable wage labor. Though capitalists of their day and left thinkers along with them believed that slavery was holding back industry, the opposite was true. When slavery was abolished cotton production fell massively and never fully recovered. The union army had to reinstate the compulsory plantation system due to the collapsing cotton economy, and when it too was ultimately overturned cotton harvests did not return to their slavery levels. Despite the arguments of the left for a hundred years slavery was an asset to capital, and its defeat led to vast changes that represent a defeat for the capitalists.[4]

The radical abolitionists are a powerful example of a revolutionary minority creating a program of action that expanded the unity of oppressed potentially revolutionary subjects (women, blacks, workers) and disorganized the ruling class. Their actions contributed to the break down of existing politics and redefined the central divisions of their day and ever since. They did so as a small relatively isolated minority and waged a war on all fronts: ethically, militarily, and through mass social organization. Their experiences brought them into conflict with the central institutions of power which had widespread support, and ultimately fed the more militantly revolutionary movements that came after. They did all this not with an alliance with the ruling class but largely against it.

The main failure we can point to is the inability to translate the victory against slavery into a victory of their other aspirations. The primacy of slavery, historically contingent and limited, was not enough to disband the power they fought, and the mass movement they contributed to remained invested in the union government. This was an obvious asset and most would argue necessity, but it also was the undoing of many of the gains made in Reconstruction. When the capitalists sought to roll back the revolt, the movement was attacked on all sides and successfully isolated. The abolitionists and insurrections (white and black) in the South failed to create a political crisis for capitalism and in doing so were vulnerable to the white supremacist reaction and assault on the working class in general that followed.

Today we live in a time of rolling crises with anemic recoveries. The embarrassing victory of Republicans with a ridiculous agenda on every front is surely sending many to despair. The left’s tiny and ineffective revolutionary minority is likewise isolated from any collective subject. Yet the repression of prisoners, immigrants, and radicals pales in comparison to the challenges of the 1830-1860s. Are our positions more unpopular than equality for women, blacks, and the liberation of workers before any such movement concretely existed?

The state’s base of support looks increasingly flimsy with widespread disillusion with all established forces, geopolitical displacement of the US’s unchallenged position, multiple conflicts looming, and disruptions from climate change on the horizon. The ruling class has shown itself unwilling and seemingly incapable of offering solutions to pressing and obvious daily issues like immigration, climate change, the growing health care crisis, rising immiseration and inequality. The journalists, intellectuals, and talking heads are persisting in defending unpopular factions and ideologies. Discontent is widespread and dissent finds little outlet, as of yet, within the existing power structure which is seemingly insulating itself against obvious reforms that might improve the situation. These are issues that anarchists and revolutionaries have concrete proposals for that answer immediate common needs. Such activity stands to discredit the ruling class and weaken their ability to govern, that is if we are able to elaborate our own and demonstrate with collective struggle how to achieve our goals and their worth.

The radical abolitionists faced down violence unparalleled in our own time with little personal gain and a seemingly hopeless situation in the environment they acted in. It’s unlikely that people had foreseen their part in the victory that came. Today as well it is hard to gain perspective as our position in history is obscured with the swirling of forces around us and the darkness that dominates our minds bombarded as we are with bad news and demoralization. What the example of the abolitionists provide is to remind us of the possibilities from where we stand, with all our weaknesses. Their victory is an encouragement to go further in owning our vision of anarchist communist society and taking action to shift the public imagination around the lines we draw and not the illusions of stability the system is straining ever more pathetically to maintain.

[1] Du Bois, WEB. (1962). Black Reconstruction in America: an essay toward a history of the part which black folk played in the attempt to reconstruct democracy in America, 1860-1880. Meridian Books.

[2] This is the central thesis and insight of Du Bois, and one who’s full significance has not been appreciated amongst those aspiring towards liberation in the US.

[3] Lewis, P. (1995). Radical Abolitionism: Anarchy and the Government of God in Antislavery Thought. University of Tennessee Press.

[4] Baptist, E. (2016). The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism. Basic Books.