Filed under: Analysis, Anti-Patriarchy, Mexico

From El Enemigo Común

By carolina

It’s getting more dangerous all the time to be a woman (or girl) in Mexico, where seven sisters, friends, comrades, mothers or daughters are killed every single day with impunity — and with a level of hatred and scorn once unthinkable. Living breathing people, now tortured to death, become a cast of characters in a macabre spectacle: There’s the girl that’s dismembered, another beaten bloody, another impaled, another stuffed into a suitcase, yet another drowned in a sewer. Virtually all have been raped. This is the face of feminicide.

Fed up with this alarming situation, women in Mexico City and the states of Guerrero, Guadalajara, Michoacán and Oaxaca, joined in the global mobilization against feminicide convoked from Argentina after the vicious rape and murder of 16-year-old Lucía Pérez, last October 8. The young girl was drugged and attacked by at least three men — Juan Pablo Offidani, Matías Farías and Alejandro Alberto Masiel — who left a pile of used condoms before raping her anally with a pole. According to the district attorney who investigated this crime, “extreme pain caused her death through stimulation of the vagal nerve,” prompting a heart attack.

In Argentina, on October 19, at one o’clock in the afternoon, thousands of women walked out of their work places to engage in an hour-long national strike — the first in the history of the country and the world against gender violence. Then they took to the streets in multitudinous marches, backed by solidarity actions in Chile, Bolivia, México, United States, Uruguay, Honduras, Paraguay, Ecuador, Colombia, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Spain and France.

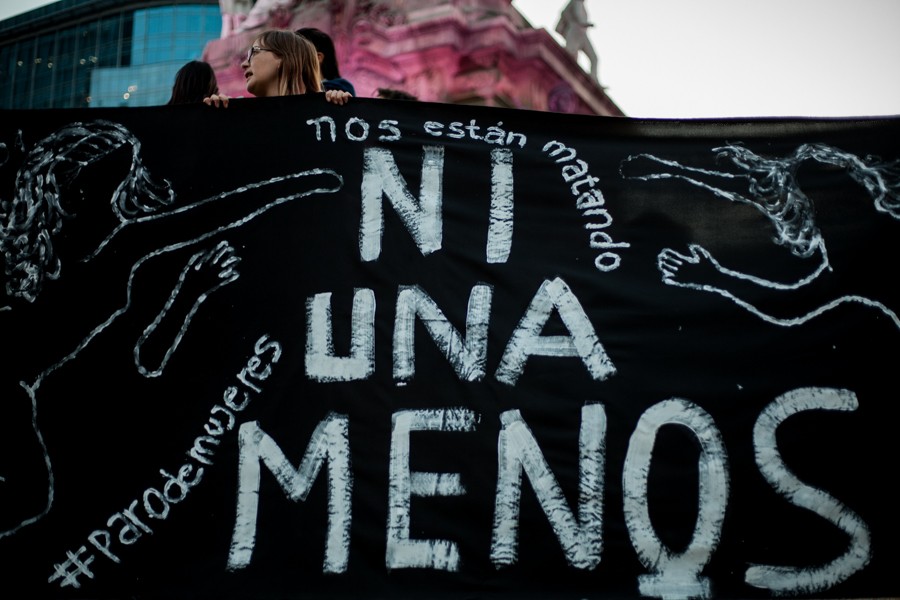

That same day, at 11 o’clock in the morning, several hundred women and dozens of men observed Black Wednesday at the Angel of Independence in Mexico City with the slogan “Not one less” spelled out on big placards. In other words, explained a young woman, “not one more woman killed, which would mean one less sister with us.” Demonstrators shouted slogans like “We want ourselves alive” to demand justice and an end to impunity for the women killed in Mexico and the world.

At 5 o’clock in the afternoon, the Monument to the Revolution was the starting point for a loud march of more than a thousand women unwilling to be victims of feminicide, accompanied by a number of men.

“We’re marching today because we don’t want to be next on the death list and we don’t want to live in fear,” said one young woman.

The marchers carried a banner that said “If you hurt a single one, we’ll all get organized” and signs saying “My body belongs to me,” “End transphobia,” “Not one more woman killed,” and “We want ourselves alive, free and fearless.”

The march was headed up by strong, upbeat drummers, chanting, “Hey everybody, don’t look the other way. Women are getting killed here each and every day,” and “I’ve got my hands, I’ve got my voice, and no stupid fucker’s gonna harm me now.”

That afternoon, while FES Acatlán students presented art and culture outside the Naucalpan Town Hall in the State of Mexico, three women and two men were arrested at gunpoint for staging a performance with spray paint. They were finally released after paying a fine.

And it was precisely in Naucalpan in the State of Mexico, last September 28, where suitcases were found containing the bodies of two women reported as disappeared several days before. Both bore marks indicating that they were beaten to death.

One of the women was 19-year-old Karen Rebeca Esquivel Espinosa de los Monteros, a student at the Technological University of Mexico (Unitec), who was last seen on September 22. She had left home to pick up a medical certificate before going to work and then to a gym. She never showed up. Little or nothing is known of the other woman, 52-year-old Adriana Hernández Sánchez. Naucalpan neighbors staged a protest, shouting “No more kidnappings!” and “No more deaths!”

The State of Mexico registered 1,045 homicides of women between 2013 and 2015, out of a total of 6,488 women killed country-wide, according to government statistics. Next came Guerrero, Chihuahua, Mexico City, Jalisco and Oaxaca, with 512, 445, 402, 335 and 291 homicides of women reported, respectively, in the same period.

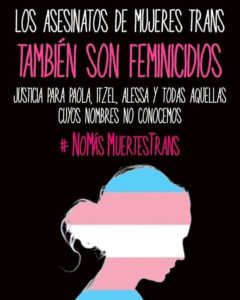

On Thursday, October 20, the lives of three transexual women — Paola, Itzel and Alessa — were commemorated in a concentration held at the Monument to the Revolution and subsequent march.

The sex worker Paola Ledezma, 23 years of age, was killed last September 30 in the Buenavista neighborhood of Mexico City, just after she got into a car driven by security guard Arturo Delgadillo, who shot and killed her with his pistol. Her workmates heard the shots, ran to the car where Paola was dying, and with the help of two policemen, took Delgadillo to the offices of the Investigatory Division of the Attorney General’s Office in the Cuauhtemoc Division, where they reported what had happened. Nevertheless, Judge Gilberto Cervantes Hernández released the killer two days later.

Itzel Durán, 19 years of age, had participated in several beauty contests and bore the title “Our Gay Beauty 2015-2016” in Comitán, Chiapas. According to reports in local newspapers, she was stabbed by two men who broke into her house in the early morning hours of Saturday, October 8. When neighbors heard her cries for help, some called 911, but when the authorities finally arrived, Itzel had already died. Members of the LGBT community have urged the local District Attorney in Comitán to establish the facts of the case and organized events in her memory.

Alessa Flores, an activist who defended the rights of transexual persons and sex workers, was found apparently strangled to death on October 13, in a room in the Caleta hotel, on Juan de Dios Peza Street, in the Obrera neighborhood of Mexico City. For the last two years, Alessa had helped lay offerings on the Day of the Dead in honor of her fellow sex workers who had been killed. She was also an activist in the Young Trans Network, where she participated in roundtable discussions and gave workshops, among other activities.

Alessa Flores, an activist who defended the rights of transexual persons and sex workers, was found apparently strangled to death on October 13, in a room in the Caleta hotel, on Juan de Dios Peza Street, in the Obrera neighborhood of Mexico City. For the last two years, Alessa had helped lay offerings on the Day of the Dead in honor of her fellow sex workers who had been killed. She was also an activist in the Young Trans Network, where she participated in roundtable discussions and gave workshops, among other activities.

According to a study of the worldwide project Transrespect vs Transfobia, Mexico ranks second among all countries in the murders of trans women. Brazil holds first place, and the United States, third. According to Transrespect, in Mexico, 11.67 percent of all crimes of this type in the world were committed, and 14.93 percent of the murders of trans women in Latin America.

After leaving the Monument to the Revolution, the trans march blocked Insurgentes Avenue and was surrounded by the police. Even so, the organizers said: “This struggle has just begun and will continue. As of this moment, the transsexual community is at war. We demand an answer from the Ministry of the Interior in person. We demand justice for Paola, Itzel and Alessa in the midst of the violence going on in our country.”

These weren’t the only actions that went on in Mexico City. As a matter of fact, the day before, university activists took over an area in the Department of Humanities of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) and organized workshops and discussion groups, while community spaces also held sessions for reflection and shared documents related to the issues of feminicide, misogynous culture, institutional violence against women, role of the State, resistance to victimization, self-defense, and non-aggressive forms of masculinity.

According to a study of the Independent Human Rights Commission of Morelos, feminicide involves the deaths of women associated with hatred, mistreatment, extreme violence, cruelty and impunity. One common factor is that the victims may suffer attacks such as strangulation, decapitation, mutilation and sexual violence. Sometimes their bodies are abused after the murders take place, “indicating cruelty, hatred, malice and scorn towards women.” Knives are often used, and the perpetrators are frequently the woman’s husband or partner, neighbors, tenants, or workmates. (Patricia Dávila, Proceso, 19 octubre, 2016 Reportaje Especial)

The following excerpts are taken from a text by an unknown author, circulated in the social networks, entitled “Blaming the Victim”:

Micaela was 12 years old. A 26-year-old guy killed her because the child didn’t want to have sex with him. But well, she had several Facebook pages where she posted “provocative” photos. What did she expect? A girl in Brazil was drugged, then raped by more than 30 men, all organized by her boyfriend as vengeance for a suspected infidelity. He filmed the whole thing and posted it on several different websites to the delight of many. But hey, the little minx was 16 years old, had a kid, and liked to get high. Just another whore…. Or Daiana, who went to a job interview at night in shorts. What kind of person would do a thing like that? A real slut. Serena was stabbed 49 times by her boyfriend because she left him, but she was just a two-bit whore. Marina y María José… traveled alone, man!! Two women alone!! What did they expect? Mailén was raped twice by Migue in his own house. But then, she’s the one who decided to go there. What did she think was going to happen? A real whore…. And we could go on and on because the list of victims of macho violence is never-ending, just like the stream of macho trash used to justify each case…. Pretty soon we may be adding our own names to this list. One at a time. It’s always easier to blame the victim.

In the following text, Macho Culture and Victimization, the issue of feminicide is approached in the broader context of capitalism:

How can we teach girls and boys not to let themselves be raped or not to rape as long as we see each other as objects of individual satisfaction? Satisfaction that may be sexual, emotional or economic, but has a common denominator: the selfishness of using somebody else as an instrument of pleasure. How can we create a new culture of respect as long as social climbing is fomented? Stepping on the head of the person beside you selfishly and smugly? How can we propose respectful relations based on the ideal of private property? How can we propose human plenitude if we’re fragmented as human beings?

During these days of actions against feminicide, a number of cases were recalled.

Mariana Lima Buendía. One of the participants was Irinea Buendía, a 62-year-old activist who has taken the first case of feminicide to Mexico’s Supreme Court. Her own daughter, Mariana Lima Buendía, was found dead in her home on June 28, 2010. Mariana had told her mother about the mistreatment and attacks she had suffered at the hands of her husband, a judicial police agent of the State of Mexico, Julio César Hernández Ballinas. He had also threatened Irinea twice with killing her daughter and “dumping her in a cistern where he had two or three other women who didn’t know how to treat him the way he deserved to be treated.” Her daughter died after the threats were made. In the activities against feminicide held on October 19, Irinea Buendía reported that even though Mariana’s case has come before the Supreme Court, impunity still prevails. “We have to raise our voices and break the silence,” she said. “That’s the only way we’ll be heard.”

And then there’s San Luis Potosí, where we can’t fail to mention a former Second Lieutenant of the Mexican Army, Filiberto Hernández Martínez. Remember him? The yoga, karate and catechism teacher who raped and strangled his students to death in the town of Tamuin? There were at least five: Adriana Martinez, 13 years old, Dulce Reyes, 9 years old, Enaí Chávez Rivera, 32 years old, and the little girls whose ages are unknown, Rosa María Sánchez and Itzel Castillo.

And then there’s San Luis Potosí, where we can’t fail to mention a former Second Lieutenant of the Mexican Army, Filiberto Hernández Martínez. Remember him? The yoga, karate and catechism teacher who raped and strangled his students to death in the town of Tamuin? There were at least five: Adriana Martinez, 13 years old, Dulce Reyes, 9 years old, Enaí Chávez Rivera, 32 years old, and the little girls whose ages are unknown, Rosa María Sánchez and Itzel Castillo.

Adriana Martínez did all she could to keep from being his victim. She had disappeared in 2011, the same year her body was found in a cane field with signs of sexual and physical violence. Even so, Filiberto Hernández Martinez was not arrested until 2014. Although he confessed in great detail the way he kidnapped, raped and murdered the young girl (and even told the court exactly where he buried her), San Luis Potosí authorities exonerated him. Only then did Adriana’s mother, Sandra Campuzano, read this line in the officer’s spine-chilling confession: “She defended herself tooth and nail. I had to hit her over the head.”

Filiberto Hernández Martinez has also confessed the murders of the other children and young women, yet many observers have predicted that he will soon be acquitted of these feminicides, as well, and will walk out of prison scot-free.

So in closing, a question arises: How do we deal with impunity?