Filed under: Analysis, Gentrification, Housing, Northwest, Repression, The State

What follows is a report back and reflection on the campaign to stop the sweeping of homeless people out of the Downtown Olympia area by private security. What it shows in the degree in which local government, police, and business worked together to attack local community organizers.

In May 2018, the Olympia Downtown Alliance (ODA), a business advocacy group, decided that letting people seek shelter in the alcoves of closed and vacant storefronts would no longer be an option in the “Downtown Commercial Core” of Olympia, WA. They acted on this decision by hiring Pacific Coast Security/Pierce County Security (PCS) to patrol the sidewalks from 8pm-12am, seven days a week. These guards were referred to as the “Downtown Safety Team” by the ODA. The beginning of this process sent shock waves through the houseless community and was one of the contributing factors to the establishment and rapid growth of Tent City, among other houseless camps in the downtown area.

According to the Point in Time (PIT) Census’ “Pre-Dawn Doorway Count,” there were 135 campers in doorways and alcoves in January, 2018 within an 8×9 block range. The Safety Team patrolled the perimeter of properties adding up to about 5 blocks of the “Commercial Core” of downtown Olympia. The Pre-Dawn Doorway Count was likely conducted in part in this exact area as the location is described in the PIT report as the “heart of Downtown Olympia.”

From the start, guards established themselves as a dominant force, with acts ranging from photographing houseless people while they slept, shining a maglite in people’s eyes, kicking people awake, and calling the police on those who refused to move. Later, they would also commit other assaults on those who tried to legally observe their actions. All of this was done with the cooperation of the Olympia Police Department (OPD).

If you read the ODA’s explanation of the Safety Team, you would assume that they did much more than simply sweep and threaten the unsheltered, but after months of extensive observation their patrols by Cop Watch, they were never once seen to execute the “key services” of sharing social service resources or acting as “hospitality ambassadors.” The Safety Team being “on-call to escort downtown employees to their vehicles” was also never observed. Regardless of whether these services were actually available, the program was inherently harmful. Recognizing this, a coalition of individuals and activist groups were called to action in June of 2018. This coalition included Cop Watch, Just Housing, The Olympia Solidarity Network (OlySol), and Olympia Assembly.

These groups ranged in tactics and general ideological stances, but found affinity in the need to end the violence of reducing the already limited options for safe and healthy sleep that houseless people in Olympia already face. Shelters are at capacity and the City of Olympia criminalizes sitting and lying downtown (where practically all services exist) and camping anywhere. The overall push by the City and downtown owners was for houseless people to be out of downtown and unseen where they would likely face higher rates of theft, harassment, and assault. A strategy involving the gradual escalation of tactics was roughly formulated and followed through with as follows:

- Copwatch was keeping eyes on the Safety Team soon after their instatement in May, 2018. They documented harassment and abuse, gathered information on the nature of the patrols and provided assistance to people facing imminent displacement.

- Just Housing, a local houseless advocacy group, scheduled meetings with the Executive Director of the ODA, Todd Cutts. It became clear very quickly that this strategy was dead upon arrival. But, important information was derived from these meetings, such as the fact that the ODA did not contribute any funds to the Safety Team program, but coordinated the contracts its members made with PCS.

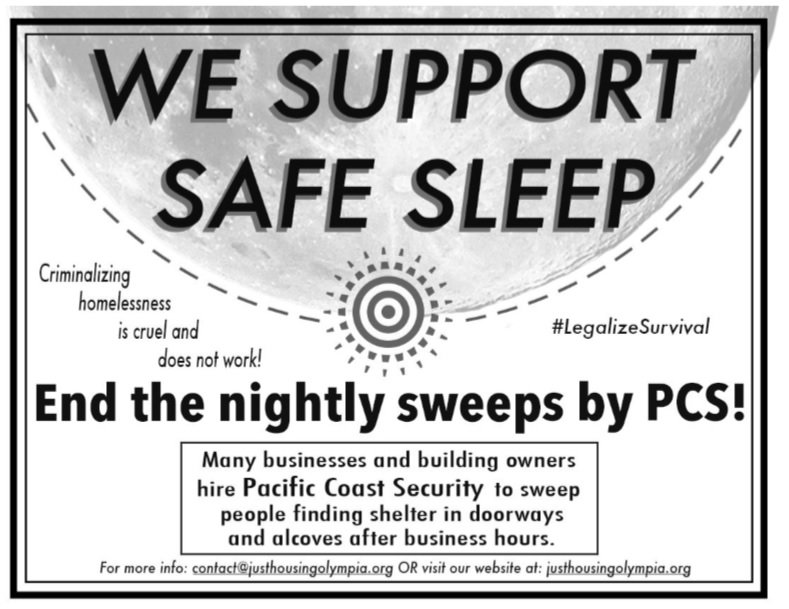

- Just Housing started a postering campaign to “Support Safe Sleep.” These posters were put up in the storefronts of businesses that supported the campaign, did not get swept nightly by the Safety Team, and felt relatively unintimidated from ODA pressure. This prompted an angry response from Todd Cutts to Just Housing and the deterioration of any ongoing relationship.

The original “Safe Sleep” poster

The original “Safe Sleep” poster

A second “Safe Sleep” poster with a rain season theme

A second “Safe Sleep” poster with a rain season theme

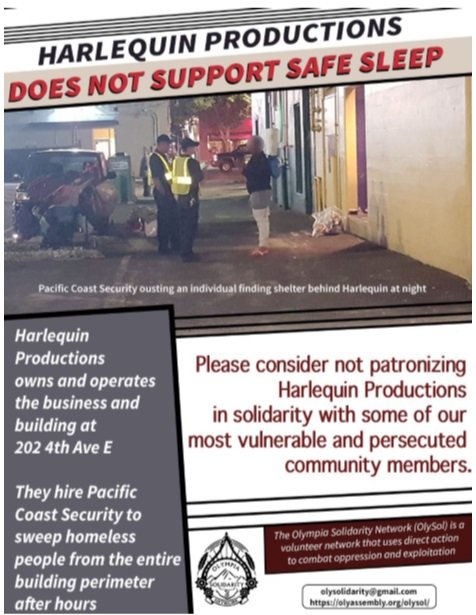

- OlySol made demand deliveries with 30 people to specific institutions that contracted with the Safety Team. This was carried out by going to the demand letter recipients’ place of business, reading it aloud, and doing a “slow clap” while leaving. The demand was to fire the Safety Team within two weeks or further action would be taken. This included a delivery to the Cooper’s (a local landed family) at their realty and construction office. Steve Cooper serves as the main face of the businesses. They own multiple properties downtown, of which two were swept nightly by the Safety Team. In fact, the Safety Team worked out of the ODA office which is housed in a Cooper owned building. Another connection was Erica Cooper, Steve’s daughter, who sat on the board of the ODA. The other demand delivery was to Harlequin Productions. This building has a large and usually unused alcove that many had formerly used for shelter from the elements. Harlequin presents itself as a do-gooder, liberal non-profit which made its hiring of the Safety Team particularly egregious. The demand delivery prompted a scathing Olympian article which featured the Todd Cutts quote in the headline, “They started from a place of threat.”

- When the demands were not met in two weeks, multiple steps were taken in a series of escalating actions including flyering, leafleting at a fundraiser for Harlequin, a phone zap against the Cooper’s, a picket at the Harlequin Productions opening night for Dry Powder, and a disruption of the nightly Safety Team patrol.

A flier that was distributed after the 2 week notice to Harlequin

A flier that was distributed after the 2 week notice to Harlequin

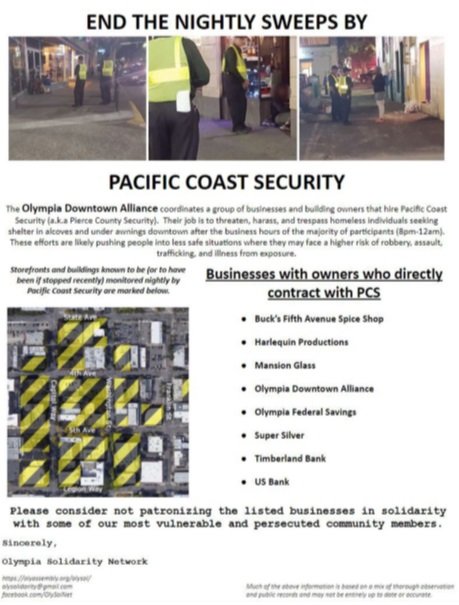

After seeing the effectiveness of the Safety Team patrol disruption, campaigners decided to focus more on the ODA and PCS, though campaigners continued to target specific businesses with flyering and pickets. Actions following this shift included leafleting at ODA business booster events, a PCS phone zap, continued flyering against the Safety Team, a rolling picket targeting 5 contract-holders in one demonstration that temporarily shut down three banks participating in the security scheme, and two more successful disruptions of Safety Team patrols.

A flier exposing the downtown private security scheme

A flier exposing the downtown private security scheme

By far, the most controversial and effective tactic was to directly disrupt the Safety Team patrols with large groups of mostly anonymous individuals. No harm was ever incurred on or threatened toward the guards; however, this tactic was still successful at stopping the guards from finishing their shift, getting the program temporarily suspended, and was a major contributor to the eventual cancellation of the contract by PCS.

To this day, there is no new Safety Team, though one was promised by Todd Cutts for 2019. This seems like it may have been an overly optimistic promise, since PCS has a regional monopoly on extremely cheap, unarmed guard services. There has been an observed increase in sweeps by OPD of alcoves since the cancellation, but not to the degree that the Safety Team did and many have once again been able to stay in unused alcoves for the night. This is roughly the same situation as before the creation of the Safety Team. The cancellation of the PCS contracts and the resulting end of the campaign took place at the beginning of December 2018, which was just after the start of the rain season in Olympia (which brought uncommonly severe conditions, hail, freezing rain, and snow storms). The fact that people were once again able to access alcoves and awnings during this time, undoubtedly prevented illness and possibly death due to weather exposure.

Why the Safety Team Disruptions Worked

The direct disruptions of the Safety Team patrols proved to be the most effective tactic in the campaign. PCS guards are usually paid around $13-14 an hour ($1-2 above minimum wage). This made them one of the least motivated and invested parties in the security scheme. The first disruption included around 40-50 people who began to follow the Safety Team a little after the start of their shift. Upon seeing the crowd, they immediately retreated to the ODA office. It was later discovered in a police report that the Safety Team had been warned by OPD of the picket at Harlequin Productions and were recommended to retreat to the ODA office and call 911 if demonstrators tried to engage them. They remained in the office and the crowd remained around the building until the dispersal upon the arrival of an OPD crowd control unit. OPD then escorted the guards from the office to police vehicles.

They were then taken to the courthouse to be interviewed. When one guard was originally asked by the 911 operator if he felt endangered, he said no. But after a few minutes with OPD on the way to the courthouse, he reversed this narrative in the official interview. After the first disruption, multiple guards refused to take the shift again, throwing the whole program into a tailspin. After nine days, the program continued with two guards consistently filling the shifts. One of these new Safety Team members was a regional manager for PCS. The other was a behaviorally unstable, older man who would laugh and exclaim with joy as he woke and threatened houseless people. This was one of the two known guards to physically assault someone (in this case, an unhoused organizer).

Eventually, the less stable member of this duo became less visible and new, not previously seen members of the Safety Team started to do shifts with the regional manager. This process of rebuilding the Safety Team took time and resources for PCS and likely marked the beginning of financial strain on the contract. Throughout this process, there were multiple spontaneous disruptions by various parties that seemed to succeed in keeping the Safety Team numbers dwindled. Many trainees were seen for only one to a couple of shifts.

A month after the first planned disruption, a second one involving the core duo mentioned above occurred. The regional manager strobed a maglite in one person’s eyes and recorded with his phone while the other guard (the older guard described above) tried, but failed, to start fights with disruption participants. This all occurred as at least 4 OPD officers watched from across the street. After the police arrived, they simply observed for quite some time before crossing the street and escorting the guards to their cars. According to the police scanner, they were driven home.

This disruption had less participants and had less of a visible effect on the Safety Team’s ability to continue with business as usual. But spontaneous disruptions continued on until another month later when a third, planned Safety Team disruption occurred. This disruption occurred very soon after the regional manager stopped attending all shifts; he was not on the shift of the third disruption. It led to the guards being escorted across the street by OPD, but they did not immediately leave. Instead, they all waited across the street for some time. Eventually, they were escorted to police vehicles and were driven away. By this point, a crowd control unit had staged a few blocks away, but were never seen to be deployed on the crowd. After dispersal into smaller groups, many people on foot were followed by OPD vehicles, but no arrests were made.

The day after this disruption, the Safety Team members did one more shift – which would be their last. The next day, it was announced to the public that PCS had cancelled their contract by an unsanctioned Facebook tirade (her account is now private) by Amy Evans, a downtown real estate broker. It was later learned that on that final shift, the Safety Team, in uniform, was getting dinner at a local bar when some, possibly intoxicated, patrons began to ask the guards what they did and if they kept people downtown safe. It was at this time that someone who relied on alcoves for shelter revealed what they actually did to the bar patrons. This caused a large number of people to become infuriated at the Safety Team at which time they quickly left the bar before their food arrived. If it were not for this spontaneous act of solidarity and rage directed at the Safety Team, the program may have continued on past the third major disruption. The reason given by PCS for cancelling the contract was safety concerns for their employees. Without the knowledge of members of the general downtown public turning on the Safety Team, this was interpreted by many as OlySol being the source of danger. What was not mentioned as an explanation for the cancellation was the act of solidarity described above or PCS’s inability to fill the Safety Team shifts with increasingly reluctant employees. This shows the importance of public information campaigns and victim involvement in conjunction with any direct action campaign like this one.

The Repression Response

Though this campaign eventually led to the successful cancellation of the PCS contracts, there were many attempts at repression that included assaults, a repression campaign by the City of Olympia targeting individuals and OlySol as a group, and petty acts of retaliation against many individuals uninvolved or practically uninvolved in the campaign.

- After the first Safety Team disruption, and its temporary suspension. There were many stakeholder meetings that included the City of Olympia and OPD. Due to recent public record requests, it is known that much of the information exchanged at these meetings involved targeting individuals that they believed to be a part of organizing the campaign. Most of these people, some of whom were stalked and photographed (online and offline), were either entirely uninvolved or were uninvolved in the week to week planning of the campaign. Partially due to their lack of involvement, they did not follow the necessary procedures to protect their identity and were targeted as a result. After the Safety Team’s cancellation, there was also a meeting at City Hall that was attended by Cheryl Selby (the Mayor), Ronnie Roberts (the Police Chief), Todd Cutts, Steve Hall (the City Manager) and Safety Team Stakeholders. The City Prosecutor was requested to be at the meeting, but could not attend.

- One of those most fervently targeted was a local professor at the Evergreen State College. The untrue and unsubstantiated conspiracy theory of this Jewish professor’s extensive involvement in the campaign was one of the main explanations for the campaign perpetuated among many downtown businesses and nonprofits. The specific claims of him controlling and manipulating those involved in the campaign were made by multiple ODA affiliated owners and echoed of George Soros conspiracies often used to dismiss left-wing discourse by anti-Semitic right wingers. Business and building owners constantly pressured the school administration to retaliate against this professor. Eventually, the school administration stated that they would not hire a new political economy professor if OlySol continued to campaign downtown. This threat was later rescinded.

•Other people targeted from all angles included Just Housing organizers who were working with the City to make sure the voices and interests of the unhoused were heard while the City formulated its homeless response plan. Due to Just Housing’s postering campaign against the Safety Team, many accused Just Housing of orchestrating the entire OlySol campaign. According to city staff, their “place at the table” was in jeopardy due to the perceived close ties with OlySol. At the time, Just Housing was also attending a large weekly meeting on the subject of the homeless response, that originally included Todd Cutts. Eventually, Todd Cutts refused to take part in them because of Just Housing’s presence, and instead got his own weekly meeting with city staff. City staff then told Just Housing that they would not be consulted with for the Point in Time (PIT) homeless count/census for 2019 because of the OlySol campaign. Being the main group providing support to encampments, Just Housing played a significant role in the success of the 2018 PIT count. With this in mind, refusing to work with Just Housing on the 2019 count, was an action that jeopardized the accuracy of the PIT Count, for the sake of political retaliation. They later reversed this threat by asking individual members of Just Housing to help. Just Housing also faced isolation from houseless and poverty focused service providers. Many of these service providers are non-profits with boards of local socialites and that receive donations from many local businesses, landlords, and governments. City staff also encouraged service providers and Just Housing to denounce OlySol, while often implying that there might be consequences if they did not. After Just Housing refused, the City began to pressure service providers and some faith community groups to separate themselves from Just Housing. This pressure on Just Housing was effective at dividing the movement at times including specific instances of siding with the Safety Team and its clients against the campaign.

•An individual allegedly involved in the first Safety Team disruption was arrested the day after it occurred and charged with two felony counts of unlawful imprisonment. After months of court and a rejected plea deal, all charges were dropped for lack of evidence.

•After this arrest was made, multiple OPD officers stalked and harassed certain individuals on multiple occasions. This included the surveillance of the entrance/exit during a music show, the cutting off of a pedestrian in a crosswalk with a police vehicle, and the stalking of pedestrians via bike. No other known arrests were made in relation to the campaign.

•A public meeting (but changed to private after the meeting started) was held to plan a lawsuit against the City for their response to homelessness and it ended in an assault against an attendee. This person was simply attending the meeting silently, but was asked to leave for being unfamiliar and assaulted by at least three men when he refused. According to the police report, these three men were Christophe Allen, James L King Jr., and Brad Balsley. After the assault and the arrival of at least 6 police officers (some with pepper ball guns), many of the +30 meeting attendees (20 of which were business owners according to the 911 call made by Jon Emmett Cushman) misrepresented events to police in a seeming attempt to incriminate the victim. Previously, on the It’s Going Down podcast, it was stated by an OlySol member that Brad Beadle, the owner of the downtown Pizza Time franchise, was one of the assaulters. This information was incorrect. However, Brad Beadle is still alleged to be a sexual predator and IWW union buster according to former employees. All involved parties were released and are currently uncharged. According to Balsey’s statement to police, the tension was largely motivated by earlier events during the meeting that were described by Balsley as “anarchist/[O]ly[S]ol/antifa interference.”

•After the Safety Team contract was terminated, a terrorist smear campaign was initiated by Amy Evans, a local, influential real estate broker, on Facebook and at City Council as well as through the Olympian publishing parts of the Evans Facebook post that accused OlySol of terrorism. Evans later went on right wing talk radio station KVI to further propagate her narrative for an explicitly right-wing audience. Evan’s mobilization of local owners to attend a City Council meeting prompted many City Council members to denounce OlySol, including another accusation of “terrorism” by Councilperson Lisa Parshley on the dais. This meeting also included a threat from Steve Hall, the City Manager, saying that OlySol needed to be “dealt with.” These ctions only emboldened those in local online anti-homeless hate groups to escalate threats of violence against OlySol and the unhoused. This smear campaign was largely concluded with the City staff coordinating an opinion piece by Ronnie Roberts, The Olympia Police Chief, in the Olympian where he states, “[Those] who terrorize those they seek to drive out are wrong… whether they use these tactics under white sheets in the South or under black masks on the streets of Olympia…”

•Though the campaign is over and the smear campaign is at least in hibernation, campaign participants are still prepared for future repression that may include lawsuits against individuals and charges being filed by the City if there are any ongoing investigations involving the campaign.

Critical Self-Reflection

- Due to an incorrect understanding of property law and who truly hired the Safety Team, incorrect information was published by OlySol. This information was later corrected during the campaign. This could have been avoided with more knowledge of the nature of property ownership and commercial lease agreements. Due to the campaign, that knowledge has been gained.

- One individual who did not effectively protect their identity during the Safety Team patrol disruptions faced politically motivated felony charges, though they were later dismissed for lack of evidence.

- During the first patrol disruption, police alleged that there were two dumpsters moved in front of one of the three exits of the building that the Safety Team was inside of. This resulted in the felony charges stated above. Subsequent discussion of this alleged act led OlySol members to agree to discourage such acts from participants preceding similar, future actions.

- Though the campaign was made up of housed, unhoused and formerly unhoused participants that was proportional to Olympia’s demographics, involvement by houseless people who primarily relied on downtown for shelter was scarce. Multiple unhoused downtown residents spoke against the campaign and there was even a direct confrontation during the Safety Team patrol disruption. To avoid this in the future, the public information component could be stronger and more widespread.

- Mobilization for the Safety Team disruptions largely relied on the “hard left” for mobilization. This often acted to alienate liberals/progressives who may have agreed with the overall goals and sentiments of the campaign. Though a serious liberal alliance was not needed to succeed for this individual campaign, the ability to sustainably prevent the Safety Team from being reinstated may rely on broader support against the program.

- The local business owner Brad Beadle was publicly accused by an OlySol member of attacking someone at a meeting, but this has been shown to be false. The actual business owner in question was Brad Balsley, the owner of B&B Sign Company. Future efforts should include better information verification processes than witness identifications alone.

- OlySol was ill prepared to counteract lies and mischaracterizations by news media outlets and social media. After the bombardment started, OlySol put together multiple responses, including an FAQ, but as far as the general public perception, the efforts were too little, too late. This may be avoided in the future by having such literature prepared before the actions that may cause such media campaigns. This can assure that the response can be a part of the initial influx of interest and not lost to the obscurity of a past news cycle.

- A lot more could have been done to make the Safe Sleep campaign more effective. Nowhere near enough time and energy was put towards this, largely because of Just Housing volunteers being spread too thin. More outreach efforts, conversations with downtown community members, and general community education about the issue could have helped with the effectiveness of this tactic.

- Differences in opinions about the effectiveness, potential harms, and unintended consequences of certain tactics among members of the various groups involved made navigating the political/community backlash of the anti-PCS campaign tricky and often divisive. It also complicated the relationship between Just Housing and OlySol and the groups’ abilities to support one another around this issue and beyond. For instance, though Just Housing was publically against the creation of the Safety Team, JH remained overall silent about the OlySol campaign. In general, both groups were careful about publically associating with one another, even for events and projects completely separate from the PCS issue. This might be avoided in the future by coming up with Points of Unity and/or deeper discussions and agreements across organizations about the effectiveness and potential harms of certain tactics.

- The OlySol campaign also contributed to retaliation against/isolation from houseless and poverty focused service providers by The City of Olympia and other downtown stakeholders. Since Just Housing has one foot in the activist world and the other in the service provider world, people conflated other Olympia service providers with Just Housing and therefore also with OlySol and the campaign. This, of course, also strained Just Housing’s relationship with some service providers, who had to distance themselves from JH to protect their programs and funding sources. This could potentially be addressed/avoided better in the future by increasing communication with service providers during campaigns that may impact them, keeping lines open for feedback from them, and finding ways to support them so they are less likely to face retaliation.

- The campaign created some common ground between The City of Olympia and business owners/ODA at a time when that relationship was relatively strained. The City (especially the City Council) and ODA were, at the time, at odds about a lot of The City’s response to homelessness. Being against the campaign was something that The City and business owners came together around strongly and publicly. This is something that would be difficult to avoid with any direct action campaign, since that is more than likely something that will always be a common ground issue for governments and business owners (such as having a nightly sweeps downtown by private security). With that said, more education about the issues and responses to mischaracterizations of actions/intentions would be beneficial for future efforts.

Overall, the campaign was successful at securing additional shelter for people during the rain season, reducing state violence (and its threat), and putting the gentrification of downtown Olympia one step back. This was accomplished with no sustainable legal charges, though it did cause extralegal retaliation from the City of Olympia and local owners towards largely uninvolved parties. Coalitions and solidarity networks, like those involved in this campaign, are replicable models that can be used to increase autonomy from owners and states while being above ground and with minimal legal exposure (lawsuits, politically motivated criminal charges, etc). This report/reflection was written largely to set the record straight and aid campaign participants in learning and growing from the campaign; however, it is also to inspire and aid in similar struggles outside of Olympia.