Filed under: Anti-fascist, Featured, International Coverage, Interviews

An Interview with Bender, a German Comrade

by Paul O’Banion

Bender has been involved in the autonomous movement in Germany since the 1980s, and talks here about his experiences and observations from thirty years of organizing. He addresses the beginnings of the autonomen – the autonomous movement – how Antifa developed out of that in the late 80s and 90s, and has developed since. He discusses where things are now, in a post-autonomous, post-antifa, German radical Left environment. He is familiar with the situation in the US, and offers lessons for organizing against fascism and all forms of domination. This interview was conducted via email, and Bender’s answers have been edited for clarity.

-Paul O’Banion

Talk about the autonomen: who you are, what political traditions and perspectives are you building on, and what has been your practical and theoretical activity.

Bender: When we talk about “the autonomen,” we speak of the 80s in Germany where the autonomen first appeared and had the character of a movement. It is one outcome of the dynamics of the so-called New Social Movements or, as you call it in the US, the New Left.

As in many other countries, the beginnings of the New Social Movements, from which the autonomous movement of the 80s was one result, was “the long year of ’68,” which in Germany is perhaps best characterised as an “anti-authoritarian revolt.” We have to remember, that the year ‘68 politically lasted much longer than one year. The movement after ‘68 reached a kind of exhaustion, in which people asked themselves how to go on, which means: how to organize a movement in decline.

After ‘68 was the “moment of the movement,” then the 70s developed along the more Party-orientated trajectory. The 70s were the decade of the so-called “K-groups.” The K-Groups were various communist groups with, in some cases, a lot of members, and in all cases – no matter how big they actually were – the aim to become a mass party. It was like the last episode of the history of Communist Parties. But whereas the first episode ended in the tragedy of the Soviet Party-State, this time it ended as the farce of communist groups run by students with nearly no impact on the working-class. But what they did have was much influence on new forms of politics and new political issues, not only those based around labor and the working-class.

But just as the student movement in the end of the 60s went into crisis and transformed itself in the decade of the communist groups, these K-groups in the end of the 70s also went into crisis. This situation split into two different ways of organizing (even if at the beginning both methods walked a short time together): the Green Party on the one hand, the autonomous movement on the other.

We see with the Green Party and the autonomous movement again the two poles, Party on one side; self-organizing, networking and an explicit politics against all kinds of state-apparatus and state-institutions on the other.

The autonomous movement of the 80s in Germany, like the radical and anarchist Left in the US, was organized around squatted houses, autonomous and self-organized youth-centers and an independent, non-commercial infrastructure with info-shops, leftist books-stores, sub-cultural spaces and so on. The model of politics was more the general assembly plenum and consensus decision-making, than decision by voting and by majority rule. Politics functioned more by events and campaigns than by following a program or a theory. The movement was more interested in practical action than in theoretical debates, and it was in general more a kind of life-style than an organized and well-reflected intervention in the political discourse like happens nowadays.

The autonomous style of politics was not only on the level of organisation the pioneer of what is today popular non-hierarchical, non-dogmatic and project-based networking (maybe we must call these kind of organisation post-Fordist or even neo-liberal?), but also the themes and issues of struggle were somewhat decentralized and widespread: anti-war, anti-nuclear, squatting, and the struggle for autonomous free-spaces, punk-music and independent labels, anti-imperialism and solidarity work for the political prisoners and so on. During the 80s, there was still something like a Left hegemony amongst youth (since the autonomous movement was mostly a youth-movement and had a lot to do with subculture and an alternative lifestyle).

All this changed at the end of the 80s. Just as the student movement of ‘68 went into decline, and the K-groups that followed at the end of the 70s went into decline, so too did the autonomous movement in the end of the 80s after about a decade of activity.

There were various reasons for the exhaustion of the autonomen:

- a “ghettoized” situation inside society that isolated us

- bad public-relations and lack of good media politics

- the beginning of neo-liberal governance that led some of the central criticisms of a standardized, normalized life to become empty, while some parts of an autonomous and sub-cultural lifestyle ironically became mainstream

- the crisis of so-called civil society, which was an important background

- closely connected with this is the decline of the various so-called Teilbereichskämpfe, single-issue struggles on various issues like anti-war or anti-nuclear energy

- the implosion of “real socialism” and the removal of the Berlin Wall, which changed the situation worldwide

- and there were new laws, especially those against the autonomous movement, for example directed against militant demonstrations and the tactics associated with the black bloc, such as wearing masks at demonstrations.

It was in this situation that the question of how to organize again arose.

This was discussed in the autonomous movement and was posed from one of the first and most popular autonomous antifascist groups, the Autonome Antifa (M) in Göttingen, but also by the Berlin group FelS (For a Leftist Current). The organizing debate refers to both experiences, on the one hand the decade of the very dogmatic theory and praxis of the K-groups in the 70s and the problems of a more closed, cadre model of organization in general, and on the other hand the problems and the strengths of autonomous self-organization of the 80s.

The most important outcome of this debate was to get organized in autonomous Antifa groups. So a lot of people that in the 80s perhaps would have been part of the autonomous movement were now organized in antifascist groups inside of what was left from the autonomous scene.

In the end of the 90s the situation changed again. Although there was still an autonomous scene, most of the political groups engaged at that time in the radical, extra-parliamentary, undogmatic Left we refer to as “post-autonomous” and also “post-Antifa” groups. That means that although a lot of the politics of those groups were still following the same radical critique, this politics is neither part of an autonomous movement nor does it run under the label Antifa.

The autonomous groups still existing can be seen as part of a more anti-authoritarian style of politics, but the autonomen as a movement is a child of the 80s and still a kind of (self-) critique of the era of the Fordist mode of production and a Keynesian-style welfare state. The crucial terms, and the attitude – of not only making politics, but also lifestyle in the radical Left, in the era after ’68 and especially in the autonomous movement of the 80s – were principles like self-determination, self-realisation and autonomy, the critique of all forms of authoritarianism, the deconstruction of all forms of representation and a general resistance against the state and the classical political parties. But all this, in a way, is now exhausted. Some of our critiques have become part of the neo-liberal mainstream; some have been overtaken by abridged anti-capitalist forms of populism; some have been adopted by the neo-liberal “technics of the self.” Also important is the neo-liberal, post-Fordist and finance-capitalist flexibilization and individualisation of society, and the restructuring of the state, with its withdrawal from social welfare, social infrastructure and an active labor market politic.

What’s important to the US context is the fact that there is not really an equivalent to the autonomen. In the US you have on the one hand all kinds of socialist and communist groups, and on the other all kind of small anarchist and undogmatic Leftist groups, but not something like the mix you find in the autonomous movement and groups in Germany. What is missing in the US, and what I search for in the German radical Left today, is both strong analyses and critiques, such as one finds in Marxism and Critical Theory, and undogmatic and anti-authoritarian form of organisation, such as one finds in anarchism, all mixed together with the spirit of punk.

What is autonome strategy? Why the emphasis on squatted housing and cultural centers, and militant street confrontations? What else is involved in autonomen activity and theory?

Bender: With the autonomous movement of the 80s, a “politics of the first person” began. That means the desire to directly engage in what we want and can do in the here and now, without delegating this to classical political forms. It was maybe the first practical consequence of what for several years, or even decades, has been called the “crisis of representation” and was an issue in philosophical texts and theoretical debates already in the 70s. This debate and these ideas influenced everything from direct militant actions to self-organized autonomous spaces. It was embodied more as a lifestyle in a healthy, radical sense, than in terms of following a theory or a classical strategy. But the basic outcome was the idea to enter in single and concrete struggles to radicalize them from inside. This could be already existing struggles like the peace movement (which the autonomen countered with the disturbing slogan Krieg dem Krieg, or “war on the war”) or struggles initiated by the movement itself like squatting autonomous youth and workers centers. It was less about following a predetermined theory, than producing a new one in practice. Namely, the theory that developed out of this was that we shouldn’t focus on class and on “the masses” or the population, but that we must take on different forms of domination and repression in order to politicise and radicalise them in the direction of an anti-capitalist critique in general. In the 90s when identity politics began, in the autonomous movement we were already struggling alongside the axes of class-race-gender; there was even a book with the title “Three to One” that was pointing to this “triple oppression.”

Are there autonomen publications, educational events with speakers or public discussions? How do autonomen engage in what Gramsci called a counter-hegemonic struggle to recreate what is accepted as “common sense?” Beyond the street battles, how do you engage the war of ideas?

Bender: This is one important difference between the autonomous movement of the 80s and the politics that followed after. In the 80s, the movement had the strength and also the self-understanding to base its politics on its own Zusammenhänge, its own relations. That included building our own infrastructure, like info-shops, book stores, publishing houses and publications, public spaces etc., but not engaging in broader alliances and cooperation with official institutions, parties and mass-media. Gramsci was not a point of reference, and in general in the movement theory was quite absent. With the transformation into autonomous Antifa in the end of the 80s this political attitude changed.

Now the aim became to still refer to our own standpoint and political forms, but to better communicate them to others outside the scene, to use contacts in the media outside our own infrastructure (which also became quite weak, while the new digital technologies arose) and to initiate broader alliances. Like always in politics, it was important to promote one’s own standpoint and ideas, and as the autonomen were in a weak position towards mass media, it was always important to use and produce spectacular pictures. Militant action, although declared as direct and practical action, have always been important on a symbolic level, which became more and more obvious and was as such taken into account in terms of strategic considerations and political praxis.

The black bloc, for example, was not only a question of self-defence, but also to show that we are here and who we are. Likewise, militant action during demonstrations was necessary because the mass media simply doesn’t report on you, but you get nationwide attention if two windows are broken.

Another important shift is that with the generation of autonomous Antifa organizing, theory became much more important. We didn’t seek to follow a certain theory like Marxism or anarchism, nor to produce our own, but rather to sharpen the critique of capitalism, its ideological effects and of everyday life, by using in an undogmatic way, various strains: undogmatic Marxism beyond Party-based communism, Critical Theory, Post-Structuralism etc.

Talk more about how Antifa developed out of the autonomous movement. How does Antifa fit into a larger strategy for building revolutionary dual power?

Bender: Like I said, in the end of the 80s the autonomous movement was kind of exhausted. This is why the question of how to organize arose again. The main problem seems to be the lack of commitment and the non-binding nature of the structures. Like always, when politics is placed more in the ambiance of a movement – and especially in one that explicitly wants to practice and realise autonomy – you had people coming and going, with no clear responsibilities or functions, no clear program or theoretical basis, no organised discussion, and no linearity, either in a theoretical or organizational development fashion. In the autonomen there weren’t really formal structures, but informal connections, officially non-hierarchical, but with internal and very informal hierarchies.

Another problem was the movement, on a personal level, had no continuity. It always depended on very enthusiastic and normally quite young people, who certainly already had some level of experience, and who would, for a certain period, sacrifice themselves for the movement, and were able to live an autonomous lifestyle. In other words, there was no place for people with children and a family, or with a 40-hour-a-week job. This problem intensified drastically in the 90s with the advancement of the neoliberal restructuring of society.

Together with this lack of formal organizing structures and lack of personal continuity, there was no transmission of lessons and experiences from the older to the younger people, or from one generation to the next, and although there were lots of endless discussions, they did not contribute sufficiently to theoretical development. It seems that we had the same discussions over and over again, and whoever felt the need for some theoretical or critical debate — like about political economy or capitalism on an abstract, systematic level — they had to search for it elsewhere. So, in short, the key words coming out of the debate were Verbindlichkeit und Kontinuität: commitment and continuity: we felt the need for continuous and binding structures.

The most important step for more continuity and commitment was to get organized in groups, which would have regular meetings and a clear membership instead of open assemblies, a common basis of understanding and common goals, and a clear name. These groups would be approachable for others outside the group, and capable of and willing to engage in alliances, they also could take better care of new, interested people, and especially of younger ones who build Antifa Jugendfront groups, groups of the “Antifa Youth Front.” The groups would also represent their positions publicly in a way that was open to participation.

Another important point was temporary alliances with other groups outside the autonomous movement, such as other leftist groups, trade unions, the Green Party, the youth organisation of the Social Democrats, and so on. But as important as these alliances were, was the necessity to maintain our positions and our forms in these alliances. That means to have – at least on a symbolic level – an autonomous standpoint and a radical expression, for example at demonstrations, by using the politics and tactics of the black bloc.

This leads to another point: the importance of better public relations and being concerned with media representation. This means some form of not really working together with the mass media, but using them to produce pictures for the public, which nowadays has become, due to the mechanism of media and politics, part of the “society of the spectacle.”

Concerning all these important points — set groups with a common political basis, engaging in media politics, politicizing the youth, making alliances with reformists, and having a concrete praxis – for all these things, the best, most important, focus was on antifascism: Antifa.

These theoretical and strategic considerations where overwhelmed and run down by the implosion of the “real socialist” states and the East German GDR and the process of German re-unification. In the early 90s this brought a general climate of nationalism and an enormous boost of fascist groups, fascist attacks, with even actual pogroms. The attacks resulted in dozens of people killed, and so Antifa then was a question of self-defence, in particular in the former GDR, where the situation still today is much worse. I think this general climate and the necessity of a kind of self-defence in the beginning of the 90s, which we called Die antifaschistische Selbsthilfe organisieren (“to organize the antifascist self-help”), is quite similar to the situation you have right now in the US with Donald Trump’s election.

But despite these reasons for generating Antifa politics, we have to remember that autonomous politics were always conceived around concrete struggles like anti-war, anti-nuclear, squatting houses, etc. But the idea was always to fight for more and to use these single issues to politicize people and to radicalize the struggles and the people who are already involved or interested in these struggles.

So antifascism is one of these struggles that represents, for us, anti-capitalism, anti-imperialism and anti-statism in general. It was one important issue the autonomous movement had in common and that could be the starting point for creating concrete alliances with others, organized around events like blockading fascist demonstrations.

These groups were usually internally organized in working-groups, with different issues, even if all the politics happened under the common term “Autonome Antifa.” The idea was still to use one single issue and one single struggle which stands for a critique of capitalist society in general, and to radicalize other people and the situation in general via Antifa.

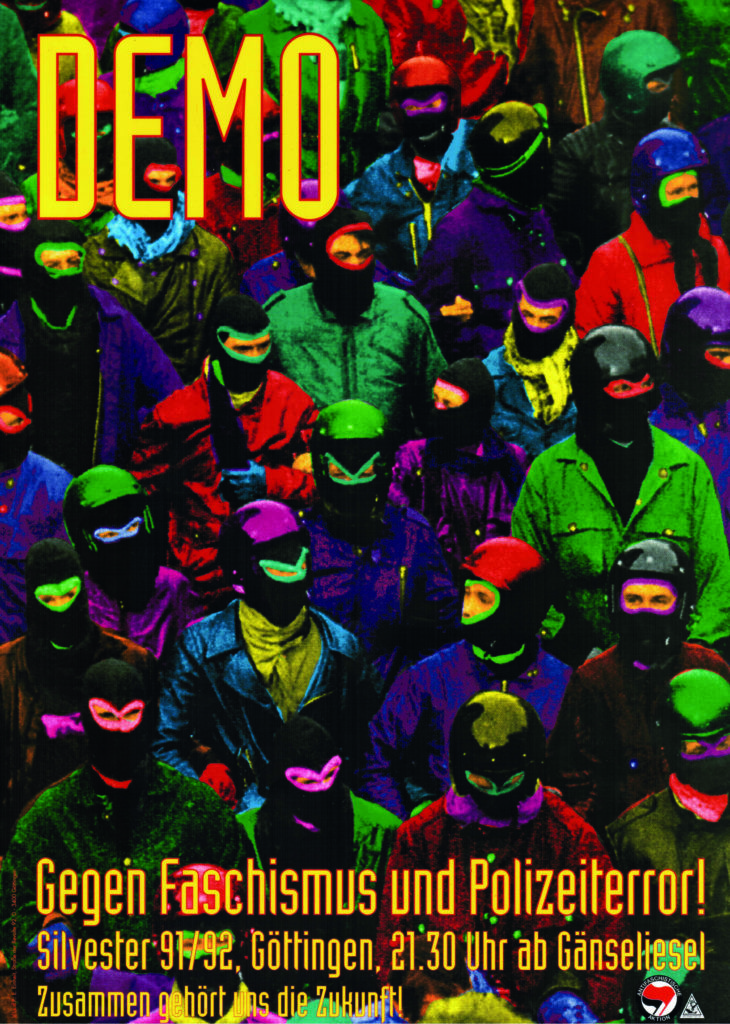

The black bloc, at the head of a demonstration against the Free German Workers’ Party (FAP), in Northheim, June 4th, 1994.

Talk about Autonome Antifa organization, from local affinity groups to larger formations. Talk about your national organizations and networks and what has worked well and what hasn’t.

Bender: The outcome of these discussions about organizing was not only a new style of politics in single Antifa groups, as opposed to lose connections around autonomous spaces and various struggles, but also an attempt at a broader kind of organizing, that means organizing on a national level.

The conflict was, in short, around the question: “organization or organizing?” The groups who advocated the building of a nationwide organization among Antifa-Groups, initiated the so called Antifaschistische Aktion/Bundesweite Organisation, AA/BO (Antifascist Action / Nationwide Organisation).

The AA/BO started in 1992 after a big meeting with a lot of interested autonomous groups, or part of the autonomous infrastructures. But in the end it only involved eleven groups and got a lot of criticism. One result of the critiques of AA/BO was the development of the more network-based structures of what was called Bundesweites Antifa Treffen (BAT). BAT started two years after AA/BO was founded as a reaction from those who saw the same need to organize but who thought it should take different forms. While the AA/BO was focused on a common praxis and unity under already quite well-organized antifascist groups, the BAT accepted a certain degree of openness and a more discussion-oriented type of organizing.

Hence the organization versus organizing distinction is represented by each of these two groups. But what both had in common was the desire to get better organized and initiating actions and alliances under the label Antifa.

But despite this difference in how to organize, Antifa in both approaches meant always more than just fighting against Nazis and their infrastructure. Apart from the fact that most Antifa groups worked on different issues (like the autonomous movement before), actions under the name of Antifa always emphasized an anti-capitalist critique and politics in various forms, and in general had a militant and revolutionary attitude.

How do you relate to other European and international movements and organizations? What does anti-imperialism look like for the autonomous and antifascist movement?

Bender: Anti-Imperialism was part of the autonomen of the 80s, but at the same time anti-imperialism was a scene and a community of its own. There were lots of overlaps, but anti-imperialist groups had their own self-understanding, and their own meetings and discussions. In this time, armed groups and armed struggle still existed, not only in Germany, but also in other European countries. In Germany we had the Revolutionary Cells and the Red Army Fraction (RAF), for example. Anti-imperialist politics often took place in the environment of this kind of armed politics, and often referred to struggles not only by these kinds of armed groups inside Europe, but also in places like the Middle East or Latin America. Organized anti-imperialist groups had in common with the autonomous movement the fight against state repression and against institutions like NATO, and we also shared the ideas of self-organisation outside classical Communist Party politics. Nevertheless, in particular, the question of the necessary level of militancy – with all its consequences – also led to controversial discussions and marked a separation of the armed groups from the larger autonomous scene.

Perhaps even more important was the harsh critique that arose in the end of the 80s, when anti-nationalism became an important position. Anti-nationalism was a common goal as long as it regarded German nationalism, which after unification became quite strong and a big problem. But the critique went beyond German nationalism and also regarded the nationalism and the nation-building in the history of “real socialism” and both Social Democratic and Communist Party politics and of the national liberation movements and anti-imperialism in general.

With regards to the old school anti-imperialism of the 70s and 80s: even if there are a few small groups left, this kind of politics is dead. It has been replaced by a new orientation that felt the need of an anti-imperialism in other forms and in particular with a new theoretical basis. The current basis for anti-imperialism is anti-racism, post-colonial critique, solidarity with refugees and the fight against regimes seeking to control migration, etc.

Talk about where Antifa is at now in Germany. In particular, I’m interested in “post-antifa” politics. Talk about what is meant by the “antifa detour.” What are the limitations of Antifa? How can Antifa fully develop into a revolutionary movement, beyond defeating fascism?

Bender: “Post-” means – like in all the cases with this prefix – that the connection is still there, that there is not something really new or different that replaced Antifa, but the actual politics doesn’t really run under that label any longer. The political work, for more than a decade, has been more about organizing, also organizing theoretical debates around capitalism, crisis and precarity, about commons and communism and so on. These groups are often also called post-autonomous. I think in the end the “post-“ is also a way back to the beginning: Antifa in all its generations and in its various stages that we can differentiate since the 70s. We have antifa that started inside the K-groups, then it was part of the autonomous movement of the 80s, then the revolutionary Antifa Groups in the 90s, followed by Pop Antifa, and now we have Post-Antifa. But Antifa has, since its beginning, been about anti-capitalism.

I think it’s not an exaggeration to say that, in general in Germany, more than in every other country, the latest generations of the radical Left were politicized by two political issues. These are a “normal” anti-capitalism, like in other countries, and by the particularity of National Socialism and the holocaust. The latter is interpreted, from the radical Left, as one reactionary answer to capitalism from inside capitalism, as an anti-capitalist revolt, or even a revolution, inside capitalism itself. But National Socialism was also a failure of the working class and its organisations as well as of the population as a whole, creating in the German radical Left, a great distrust against any forms of populism, nationalism, and short-sighted anti-capitalism, together with a consciousness of the importance of anti-Semitism not only for the whole idea and ideology of National Socialism, but for the way in which capitalist modernity and it’s crises were ideologically digested and “resolved” by the masses.

But I think the real object of critique is the inner connection between capitalism and fascism and other authoritarian forms of politics and the turn from liberal democracy into its Other. And the same goes for other forms that the radical Left is criticizing, like all the forms we have in the so-called identity politics. The connection between capitalism and sexism, and racism, and anti-Semitism, and homophobia and so on, needs to be made explicit. To critique this inner connection to capitalism on a theoretical and political-practical level, already is a radical and even a revolutionary politic.

In the case of Antifa, this connection is “only” the most drastic, and sometimes the most urgent one. Here the connection with repressive, anti-emancipatory forms is not only more drastic, but here different ideologies overlap. The limits are the same as in other issues. People say “OK, fascism is bad, like racism, sexism, nationalism and so on. But liberal democracy, law and order, the state and its institutions can protect us. Capitalism is not responsible for these forms.” And that’s all true. And still and nevertheless, on the one hand we must insist that we can’t talk about these forms without talking about capitalist forms and how they, besides its “pure” economic inequality and associated problems, also produce ideology. And on the other, we must use this “pure” capitalism to criticise its abridged, ideological forms of (self-)critique like in the anti-capitalism of National Socialism or in right-wing populism. So our critique of capitalism is also that it produces its own abridged ideological understanding. The devastation of neo-liberalism is not only economic, but is also social, and the immiseration and the poverty that capitalism today leads to is, in our societies, less economic, but more social, cultural and political.

What lessons has Antifa learned over the years in Germany that would be helpful to those of us in the US organizing against fascism.

Bender: With regards to the concrete situation you have in the US right now, it seems similar to the situation in the beginning of the 90s in Germany, when after Unification we had a political climate that gave an enormous boost to nationalism in the whole society and to fascist groups in particular. Our answer was to organise for self-defence and to propagate that.

But today in the US this climate has not come about by the implosion of “really existing socialism” and Unification, but by the crisis of finance capitalism and the delegitimation of neo-liberalism. This brought first authoritarian-technocratic solutions, still run by the “old elites,” and has now been taken over by right-wing populists, religious fundamentalists and the also “light” forms of fascism. These forms should be confronted in a different way than old-school fascism, and here all antifascists are in the same situation. Maybe the US is advanced as this populism is already in power, like in Hungary or Turkey.

But one of the few cool things in the German radical Left is that in Antifa several things came together. German Antifa developed analysis, theory, and critique as radical as Marxism and Critical Theory and organised as well as the K-groups of the 70s did. But at the same time we were against authoritarian and repressive forms, as informed by anarchism, and all that was done with the spirit of punk, and sexy and forever-young as pop. I don’t say that all this is fully realised, but the aim and desire is there. I don’t know if this is helpful for comrades in the US, but I don’t see this combination there and I know that comrades in the US also miss this mix of elements, too. In the US, the different political and subcultural scenes seem quite separated but maybe they are ready to get more mixed.

Also, in going into broader alliance with non-radical Leftists, I think this attitude we tried in German Antifa helps: to be as radical as possible in theoretical analysis and critique, irreconcilably against fascism, and true to one’s own experience and militant practice, but also flexible in different situations and with different political partners.

What further was important for German Antifa was to use antifascism to address the hidden connections of capitalism, liberal democracy, and individual freedom turning into its own opposite: into fascist ideology, fascist mass movement, and the devastating politics of fascism in power. This is what distinguishes autonomous and anti-capitalist antifascism from other political forces: not only the militant actions against fascists, but the radicallity of the critique. So anti-fascist research, counter-mobilisation, doxing etc. are an everyday duty, but the real purpose is to address this blind spot inside capitalism and in the self-understanding of capitalist bourgeois society.

What was also new in German Antifa was to turn around the understanding of the relation between theory and practice. Militant action in hard street clashes and direct actions is always, in non-revolutionary times like theses, only symbolic. It is important to bring ideas into a broader public view, so in a way direct actions and street fighting have an abstract and theoretical impact. The same goes, but in the opposite direction, for organising and creating theory: it is always, even in the most abstract forms and styles, very practical. It is important to work to change people’s consciousness and go beyond the status quo, and in theory and critique we have this free space to be as radical as possible – which we can’t currently be in political action.

So on the one hand, theory and practice that are interchangeable and even the same, but on the other hand we have to accept this gap between them and deal with it. But significantly, we can also turn this gap into a strength. We can go in our theoretical work much further than we can currently in our political praxis, and vice-versa. And in our practical politics, we can keep calm, concentrating on symbolic and subversive actions and their impact. But because we are not in a revolutionary situation, or in a situation where every strategic or tactical mistake can have huge consequences, we are free to be creative.

Bender has been involved in the autonomous movement in Germany since the 80s, in Autonome Antifa (M) and the nationwide organization AA/BO (Antifaschistische Aktion-Bundesweite Organisation). He’s taken part in all the “big events,” like the G8 and G20 protests and annual May Day actions. He is currently involved with TOP (Theory, Organization, Practice) in Berlin, which is part of the national organization Ums Ganze. Ums Ganze, an alliance of anti-nationalist, post-antifa groups that focuses on the critique of capitalism directly, and is part of Beyond Europe (beyondeurope.net)

Paul O’Banion is a long-time anarchist organizer, once part of the Love and Rage Revolutionary Anarchist Federation and other anarchist and radical groups. Still active, he has been a participant in anti-racist and other militant actions since the 80s.