Filed under: Editorials, Insumisión, Mexico

Originally posted to It’s Going Down

By Scott Campbell

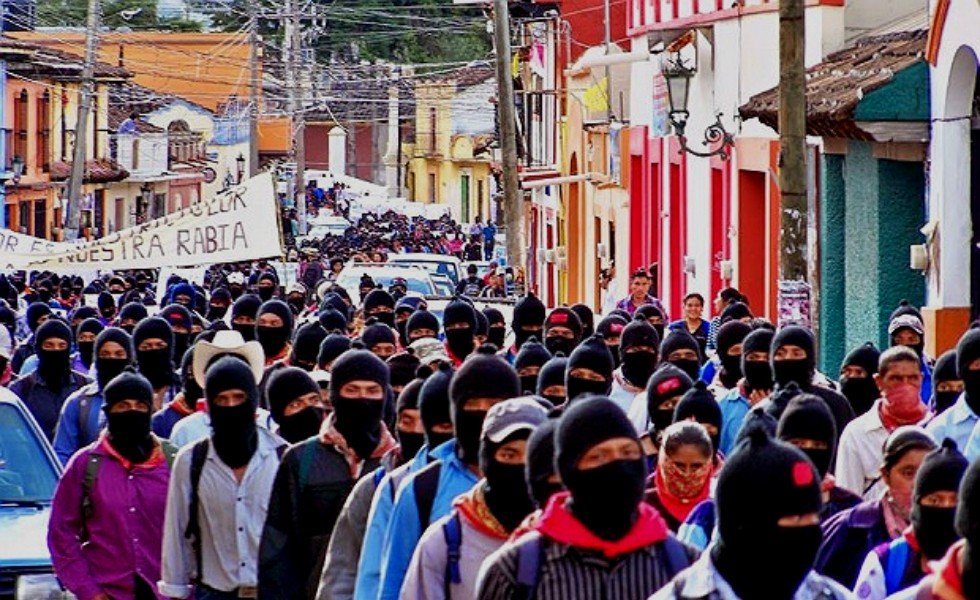

Happy May Day! Around Mexico today numerous marches will be held, primarily organized by the National Education Workers Union (SNTE) and its more radical tendency, the National Education Workers Coordinating Body (CNTE). A few of the demonstrations are listed on It’s Going Down’s roundup of May Day actions. These marches are usually large, as the teachers union requires their members to show up. That extra incentive probably isn’t needed this year, as the teachers are fed up with the state’s repression and attacks on public education. The CNTE has already announced an indefinite national strike for May 15, and as a warm-up held the largest march in its 37-year history in Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Chiapas on April 22. Stretching more than three miles with 100,000 participants, the march was in response to the repression faced by teachers there the week before. While the CNTE base has consistently demonstrated its militancy, the leadership remains stuck in the politics of respectability, as demonstrated during the April 22 march when they ordered that “no one should commit acts of vandalism and that anyone caught would be detained; that no one would be masked or cover their face.” The gap between the two seems likely only to widen as the union’s actions intensify.

When it comes to teachers and protests, fresh on everyone’s mind is Ayotzinapa. When it comes to a relentless dedication to preserving impunity at all costs, the Mexican state is quite impressive. This was on full display last week as the Interdisciplinary Group of Independent Experts (GIEI) sent by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (CIDH) released its final 600-page report in a four-hour press conference on April 24. The GIEI’s mandate was cut short by the CIDH following the Mexican government’s consistent harassment, subterfuge and non-cooperation. “The experts assured that the authorities have not followed key lines of investigation, evidence has been manipulated, obstructed and investigative work rejected, officials that would have participated in the disappearance protected, and alleged suspects tortured to obtain confessions that support the government’s version.” The details are too expansive to explore here, but the short version is that the GIEI found the students were under surveillance, the attack on them was recorded and coordinated among local and state police and the army, and that the head of the Criminal Investigations Agency (akin to the FBI in the US) had a personal role in manipulating evidence and illegally detaining and torturing someone who later “confessed” to involvement in the disappearance.

In response, Tomás Zerón, the head of the Criminal Investigations Agency and confidant of President Enrique Peña Nieto, gave a press conference where he lied unapologetically and presented doctored footage to support his deceit. The GIEI immediately responded, notifying Zerón that he is “distorting reality.” The UN High Commission for Human Rights in Mexico “denied” and “disassociated” itself from Zerón’s statements. And to pile on, just days prior, the Argentinian Forensic Anthropology Team released its report, noting that the government’s version of events “is not possible.” Nineteen months after the disappearances, the students’ relatives continue to mobilize and are now demanding the resignation of Zerón and for the Mexican government to accept a new investigatory mechanism proposed by the CIDH after the GIEI was essentially run out of the country. The government has yet to reply to the CIDH’s offer.

The UN Commission has also been visiting several communities under attack in the State of Mexico, including Xochicuautla and the National Commission for Human Rights has announced it will be taking that state to the Supreme Court in an attempt to block the recently approved Eruviel Law, which allows police to open fire on protests and meetings. One Mexiquense community that knows what it’s like to have the police open fire on them is Atenco – or “riot town” if you’re the BBC – where the government is again trying to move forward with plans to construct Mexico City’s new airport. When construction materials were moved onto their lands, Atenco’s residents responded by appropriating those materials. They have released a call for people to gather in Atenco on May 3 – marking ten years since the brutal attack on their town spearheaded by Peña Nieto – to dig trenches to block the entry of more construction equipment. “The only thing we have to do is to defend our land…we’re not going to let them have even a single fucking meter, let that be clear.”

Inspired the Basque and Palestinian struggles for their prisoners, social movements in Mexico also mobilized on April 17 to call for freedom for their political prisoners. The ejido of San Sebastián Bachajón, adherents to the Zapatista’s Sixth Declaration, called for the release of its three political prisoners in Chiapas. “To be committed to your people doesn’t mean to commit a crime. They are jailed and treated inhumanely for their struggles. They demand their rights, but the government turns a deaf ear.” Relatives and comrades of Alejandro Diaz Santíz, whose case was mentioned in last month’s Insumisión, marked the day by establishing an encampment in San Cristóbal de las Casas. In a statement they said, “To support the resistance of political prisoners in Chiapas, as well as that of Leonard Peltier and Mumia Abu-Jamal, jailed in the U.S., of the NO TAV Movement prisoners in Italy, of Marco Camenish and the other persecuted and jailed anarchists in Operations Pandora and Piñata by the Spanish State or of the hundreds of political prisoners of Euskal Herria [Basque Country], is to support the humanity that flourishes and struggles even in the blackest darkness of the dungeons of power.”

Also on April 17, in a community assembly the Otomí town of San Francisco Magú in the State of Mexico decided to not recognize or allow the authorities appointed by the municipal government to operate in its territory. They have taken a building from which to operate their autonomous project, and with it seizing the local water utility. In their next assembly, they vowed to take actions to ensure that their “autonomy is not only respected but deepened.”

In ejido Tila in northern Chiapas, the five-month long autonomous project in the Chol community continues. A recent article, available in English, discusses what the community has done to ensure everything from security and justice to keeping the sewers and streets clean. Without mentioning the autonomous project another translated article provides context about the “new reality” in Chiapas, in particular in Tila, and the inability of the Zapatistas to counter the growing power of narcos and paramilitaries, leading communities such as Tila to take matters into their own hands. A similar situation is unfolding in Simojovel, where a local priest organizing against corruption and drug trafficking reportedly has a one million peso bounty against him. If you have 30 minutes and speak Spanish (or Russian), check out this interview with Subcomandante Moíses from last week talking about the current situation of the Zapatistas. It’s one of, if not the, first interview he’s given since becoming the EZLN’s spokesperson.

In other struggles for autonomy, twelve members of the community assembly from the autonomous Mazatec municipality of Eloxochitlán de Flores Magón in Oaxaca have been held prisoner for 18 months. The community has begun to organize a new initiative to demand their release and preserve its autonomy. “Our struggle is for the defense of communal territory. And for the defense of our traditional communal system of assembly and direct democracy, and so that the political parties are unable to establish themselves in our communities…to be not divided and corrupted.” One of the most powerful examples of self-determination and autonomy in Mexico continues to be the small Pur’épecha city of Cherán in Michoacán, who in April celebrated five years since they rose up against the government and organized crime. They stated:

The civilizational crisis we had, that we were looking at before April 15, and that the whole country is still living, a reification and destruction of the environment and of human relationships, made us wake up as a community, as an autonomous process, as rebellion, as a social movement, we can find a thousand names but offer one solution, to return to our roots, to our own principles, to return to something we knew and were living, to set 186 bonfires, to make barricades and community patrols, these aren’t by chance, it is all a response to the cry of depredation and inhumanity we were living in.

On April 24, 27 of Mexico’s 31 states, as well as Mexico City, saw demonstrations to mark the National Mobilization Against Sexist [Machista] Violence. What began as a suggestion by one woman on social media in Tuxtla Gutiérrez was seized upon and led to tens of thousands taking to the streets to protest the relentless wave of gender-based violence in Mexico. A report by Revolution News noted the following grim statistics: “63% of Mexican women report having experienced some kind of sexual violence. The statistics increased to 72% in Mexico City. El Pais reported that various prosecutors’ offices have registered more than 15,000 complaints of rape per year, around 40 women per day. At least six Mexican women die per day at the hands of men. 50,000 women have been murdered over the past 30 years.”

A few more pieces of news to round out this edition. On April 14, all major political parties voted to approve new “Special Economic Zones” in southern Mexico, establishing “preferential conditions for national and foreign private companies” including tax and customs concessions. In Caborca, Sonora, police arrested 11 members of the community resisting the Penmont gold mine, claiming they somehow stole “more than 120 million gallons of a gold-rich cyanide solution, which if managed without proper equipment causes death and requires at least 15,000 cistern trucks to move.” On April 23, journalist Francisco Beltrán Pacheco became the fifth member of his profession to be killed this year in Mexico, in Taxco, Guerrero. And in a couple of attacks on the social peace, Informal Anarchic Individualities claimed an explosive attack against the government-run CORTV media outlet in Oaxaca, while days later in Mexico City the Green Child Cell, Blue Child targeted a car dealership with explosives:

Today, April 26, 2016, at approximately 3-3:30 AM, while the stinking slave masses gather energies in their bedrooms to rise early and work, while many people dream of saving money to buy luxuries and climb the social pyramid, we scurry our plague towards one of the most widely diffused and accepted symbols of techno-industrial, modern, capitalistic society: the car.

Three students remain hospitalized in critical condition in Michoacán after police violently attacked their protest of an appearance by the Secretary of Public Education. Fifty-two other students were arrested. Six years ago, on April 28, 2010, a solidarity caravan headed towards the besieged autonomous Triqui municipality of San Juan Copala in Oaxaca was attacked by government-backed paramilitaries. Bety Cariño, head of Community Support Center – Working Together (CACTUS) and Jyri Jaakkola, a solidarity activist from Finland, were killed. Despite issuing 11 arrest warrants and having knowledge of where the wanted individuals are, the Federal Attorney General’s Office on April 27 instead decided to close the file on the attack and no longer pursue their version of justice. Bety’s relatives stated, “We also want to say that we don’t believe in their justice, which is merely a mask that creates an illusory idea that justice is possible in the capitalist, patriarchal system of death.”