Filed under: Critique, Development, Housing, Southwest

From FireWorks

A piece from issue number six of local anarchist newspaper EastWest titled “Elaine Brown’s Second Plan,” with a brand new post-script which elaborates on the themes of the original article.

A story on a planned housing development in West Oakland has been making the rounds in the news recently. With the never-ending list of new developments popping up all across the area, what makes this one grab the headlines? Several things: the project was in part founded by ex-Black Panther Elaine Brown. The development also functions as a prisoner re-entry program, providing jobs to ex-inmates and housing to low-income families. They plan to build a community garden, with aspirations of a juice bar, fitness center, tech business, and shoe and clothing manufacturing companies not far behind. All this will be housed in a high rise building with as many as twelve stories, sitting atop the now-vacant lot at 7th & Campbell.

Providing housing for low-income families and jobs for those returning from incarcerated life is perfectly fine, but placed in the context of the gentrification epidemic in West Oakland, this development will probably act in concert with other proposed developments to further cement the fantasies of the rich. As luxury housing and upscale businesses sink their roots into 7th street, more and more wealthy (white) people will rush to the area and what constitutes “low-income” for Elaine’s development will continuously rise in price.

Beyond this, it is in the interests of the developers and future residents of the luxury housing to create an incubator of ex-prisoners and low-income families, keeping them in a single easily manageable space that will likely be aesthetically indistinguishable from the surrounding landscape. As for the proposed business projects, in the most optimist of perspectives, they will only serve to integrate a select few compliant low-income families and ex-prisoners into the “new Oakland” that is being built, perhaps as the token representation of it’s supposed diversity. Less optimistically, poor people (largely black and brown) will spend their days working at the farm, the bar, the manufacturing plant, in service of their new, wealthy neighbors.

Is this criticism of a development project proposed by a former Black Panther to harsh? Surely someone coming from such a radical background would have better intentions than described. And perhaps that’s true – Elaine Brown might very well have the best intentions, and she is certainly sincere. Along with family of Kenneth Harding, Elaine Brown helped organize the shutdown of the MUNI train system and helped oppose the WOSP development plans.

However, this would not be the first time her enthusiasm for a project has been misplaced. In the seventies, after using her leadership of the Panthers to get certain politicians elected, including former Mayor Lionel Wilson, she poured enormous effort into the construction of the Grove-Shafter freeway (I-980) which is now largely considered to have separated West Oakland from the rest of the city, reinforcing its position as the “ghetto.” Mayor Lionel Wilson also oversaw a significant amount of development in what is now known as the Oakland City Center, though several of the projects began before his term.

As discussed in our last issue, opposition to gentrification cannot take place within the capitalist system. Simply put: there are no solutions to be found within the market. As long as one class of people own property, they will drive up rents and people will be pushed out. Ultimately, they have the power of the courts, the police, and the government on their side – we only have each other. Despite Elaine Brown’s best intentions, this new project only pushes the agenda of gentrification forward. She only has a year-long development license and is in search of investors, so it remains to be seen what plans will be cut and left behind as it comes to fruition, if it happens at all. This isn’t to say that ordinary people cannot do anything to fight against sky-high rents, but it means not waiting for someone to save us, for new laws to be passed, or for new politicians to be elected. It means taking action now, organizing rent strikes, occupations of buildings, and organizing in our our neighborhoods, and taking back everything from the rich and powerful.

A year later, and Elaine’s grand vision has yet to come to fruition. The graffiti has been covered up and a community garden is maintained but there does not appear to be much progress in the business incubator she dreams of.

Despite the seemingly slow momentum, the project is still ongoing. An article on their activities was published recently in the SF Chronicle, including the following passage:

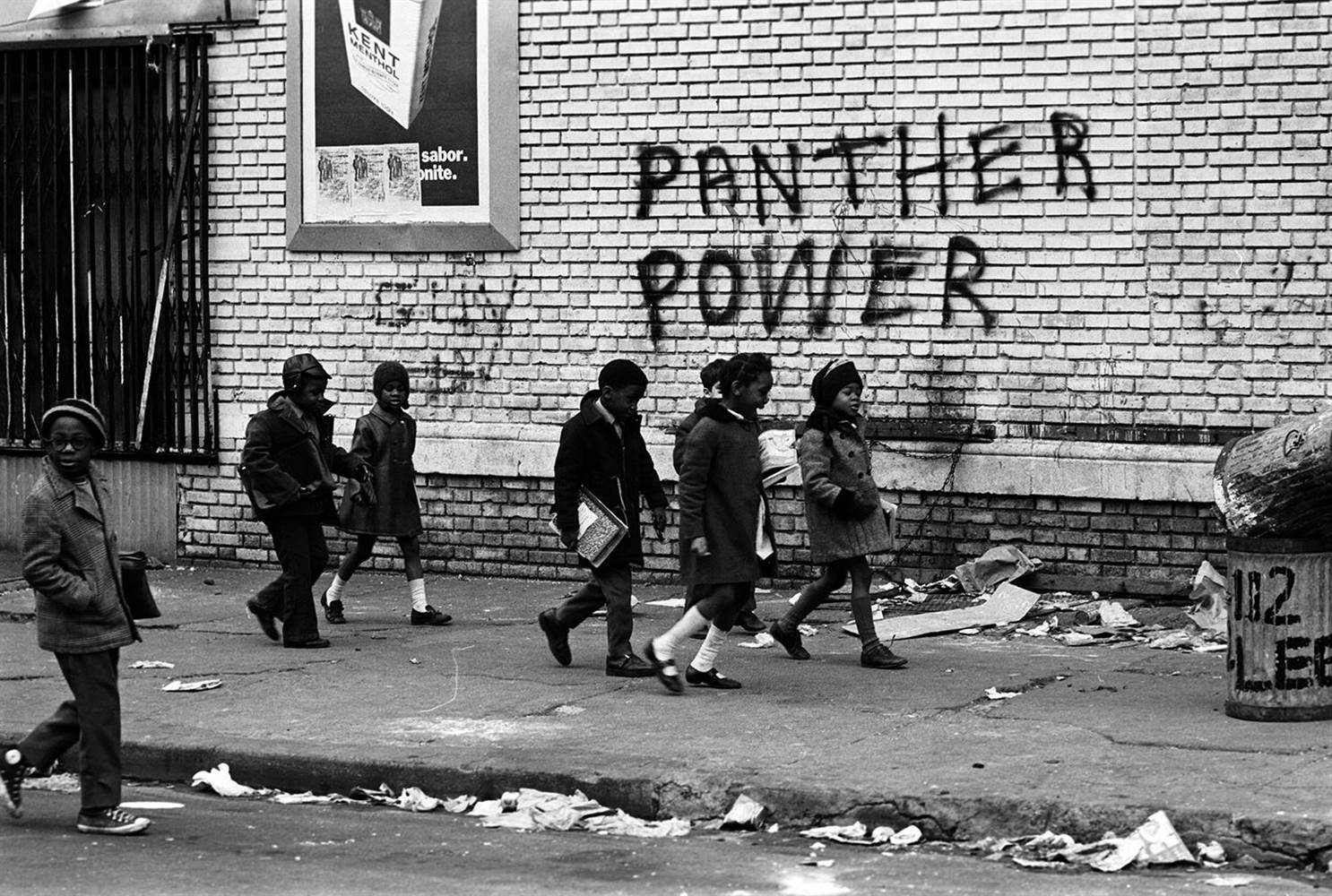

Some may see the farm as a manifestation of the Bay Area’s tech startup culture. Yet Brown also sees it as an extension of the work the Black Panther Party accomplished in West Oakland in the 1970s, when it organized free breakfasts for schoolkids, grocery giveaways, urban gardens and health clinics.

Interesting to note is that Brown does not see any inherent contradiction between the Bay Area’s tech culture and the work of the Black Panthers. What made the Black Panthers so powerful as an autonomous force was that their programs existed outside of and were antagonistic to the social order. Their programs were not sanctioned by the state, and they resisted integration into capitalism. On the other hand, this new development is founded for that very purpose—integration into the capitalist economy.

Although the article focuses on her personally, it might not be fair to focus our critique on Elaine Brown herself, as her involvement is incidental. She is in fact only one of several board members in the project. The rest of this list is a fairly predictable collection of bureaucrats, bankers and politicians. And of course, there is a bigger picture than just one project.

Another project with this same idea based in East Oakland was recently given a large grant from Google. This time, it’s about helping formerly incarcerated and low-income workers get jobs “in Oakland’s burgeoning ‘foodie’ economy.” The group, Restore Oakland—part of the Ella Baker Center—is headed by a former director of EcoDistricts’ Target Cities—all about urban revitalization. Suffice it to say, that all the good intentions in the world don’t make up for the actual mechanisms of gentrification that are driven by these projects.

Google is attempting to soften criticism against it with this and other grants to “racial justice causes.” This might work for the activists who think Google and other tech companies are inherently neutral entities that can choose to “not be evil” but this ignores the damage fundamental in the tech industry, and in capitalism itself. And that is why all attempts to integrate anyone—even those who are marginalized—into capitalism must be opposed.

For a moment, let’s return to a point made in the original article.

[I]t is in the interests of the developers and future residents of the luxury housing to create an incubator of ex-prisoners and low-income families, keeping them in a single easily manageable space[.]

Which is reminiscent of a definition of gentrification that appeared in french journal Tiqqun:

[T]he progressive gentrification of previously secessionist places, in the uninterrupted extension of the network of apparatuses.

While this definition misses the racial dimension that gentrification takes, it allows us to better understand why projects such as Elaine Brown’s are beneficial for our enemies. Places “previously secessionist,” in that they resisted the social order, are redeveloped for the purpose of policing the area and making it economically profitable. Compare this new development with the nearby ACORN housing development:

The physical layout of space, its geography and organization, determine how power can flow within. A critique of space and the way it governs relationships is not solely the domain of radicals and antagonists. Older developments such as the ACORN projects in West Oakland have been able to act as hubs for illegal capitalism because their architecture was opaque to social control. These mistakes in development culminated in a counter-insurgency-style raid on the projects in 2008, with 400 police and at least one armored personnel carrier. (Bay of Rage)

Because ACORN was built in a way that was not conducive to policing, the residents and their activities were opaque to the eyes of the state. Building developments that are conducive to policing are almost useless to power if only those who are obedient to the social order—those who can afford high-rise condos—occupy them. This concept of opacity is discussed further in popular text The Coming Insurrection:

Today’s territory is the product of many centuries of police operations. People have been pushed out of their fields, then their streets, then their neighborhoods, and finally from the hallways of their buildings, in the demented hope of containing all life between the four sweating walls of privacy. The territorial question isn’t the same for us as it is for the state. For us it’s not about possessing territory. Rather, it’s a matter of increasing the density of the communes, of circulation, and of solidarities to the point that the territory becomes unreadable, opaque to all authority.

It ought to go without saying that this is not an endorsement of “illegal capitalism,” but an example of the potential that can be found in so-called “zones of opacity.” This is what made the Black Panthers such a notable adversary of the social order—the density of solidarities, their ability to support and defend one another without and against the system that dominated them, and dominates us today.

Tags: Black Panthers