Filed under: Analysis, Anti-fascist, Community Organizing, Ontario, White Supremacy

What practical lessons can be drawn from community defense in Toronto?

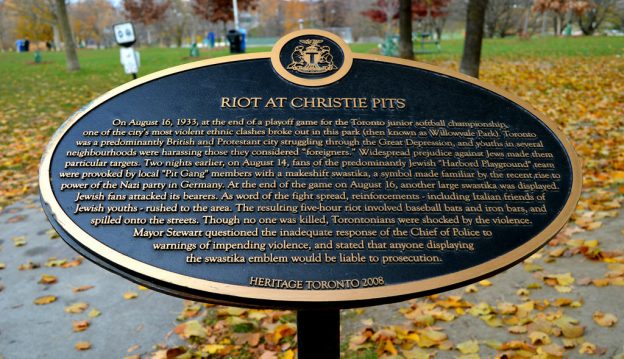

On Sunday, members of the antifascist community and the wider public in Toronto gathered to commemorate the August 16th 1933 Christie Pitts Uprising, often called a riot. This jovial community-oriented gathering brought people from various ideological lines together in reflection on the actions taken to defend the Jewish community in Toronto from then-Swastika Clubs and on the solidarity given between then-marginalized communities (primarily Jewish and Italian baseball club members).

As noted by Canadian-Italian publication, Panoram Italia, in an overview of Jewish and Italian collaboration, at this time “newspaper articles reached Toronto bringing word of the atrocities that the Nazis were committing against the Jews. As a result, many Anglos began forming Swastika Clubs, attempting to have Jews and other ‘foreigners’, like Italians, banned from the Beaches area.” This aim towards genocide and exclusion fueled the coming uprising in its start. In no way was this a sudden incident, but one grounded in growing community tensions and clear needs for community defence.

The August, 17th 1933 Toronto Daily Star reported the Uprising in its account in every confrontational detail. Yet their tone was a familiar one to anyone following the accounts of anti-fascist resistance today.

Both fascist and anti-fascist groups along the neighbourhood had long known of the possibility for confrontation that particular evening and local police, it seems, knew so as well (even if reports of police presence on the day was particularly low and disorganized). Aside from visual provocation, fascists made direct threats towards members of the Jewish community. In one instance, resulting in the injury of one Joe Goldstein:

As an illustration of the community nature of this resistance, Goldstein was later saved by one Joe Cancelli, an Italian community member who pulled Goldstein from the fascist grasp. In turn, while the Star gushed over weapons and injuries in text and in photos, the fascists admitted their role in starting the affair.

Meanwhile, resistance spurred forced a legalistic response from a city that had rested on its laurels until then, as the Star also then reported:

“For every Heather Heyer, there are countless black, indigenous, and other people of colour, queer and trans people, disabled people, and others who too have and will continue to suffer if we remain aloof.”

But, however some officials may have depicted their actions at the time, in the end, it was not some legalistic process that began movement against the fascists in Toronto, but instead deep community solidarity and common defence. The everyday person within Toronto’s Jewish and Italian community, not the State, put the fascists on notice.

Stories such as these and of other forms of anti-fascist resistance (like resistance to the Edmund Burke Society and the Heritage Front, or the Allan Garden Riots in 1965) are incredibly important to reflect on in this era of rising white nationalism and neo-Nazism. As with solidarity between the Jewish and Italian communities of the 1930s, there are many peoples coming together to resist in modern Toronto. Organizations and networks have been developing and reconfiguring across Toronto and beyond in the face of consistent right-wing violence—from the Quebec City mosque shooting to the Unite-the-Right murder of Heather Heyer in Charlottesville. In Toronto too, as I’ve previously argued, we see the germination of a neo-Nazi bloom.

But, what can antifascists and yet-uncommitted folks in Toronto learn from the specific resistance eighty-four years ago?

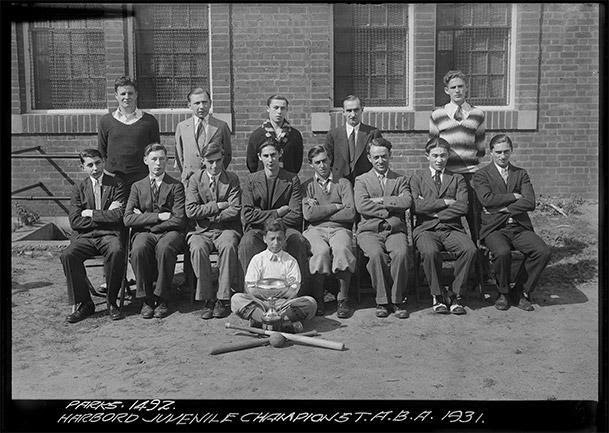

Harbord Playground team with coaches and manager, 1931. Photo: City of Toronto Archives, Series 372, Sub Series 52, Item 1492

We Need To Build Coalitions

No one community could have addressed the issues of Toronto’s Swastika Clubs alone and, unchecked, they would have continued to grow in strength within the city. The community coalitions developed to push them back and engage in community defence were critical in moving conversation beyond a liberal one of mutual violence and towards a conversation of making fascism unacceptable within public discourse and action. No politician or state force made this so, but coalition of everyday people impacted by these groups.

We Need To Take This Seriously

Surrounding Christie Pitts, members of the Jewish and Italian communities did not hesitate to recognize the immediate seriousness of the rise of fascist clubs within their area. Nor did they wait on a political establishment that sat on their hands while such forces grew. Instead, they acted. The seriousness of these threats have arrived for many communities at different times (most recently, for the middle class, white community across North America with the death of Heather Heyer in Charlottesville), but are long lived for many communities. Just as communities then and people of colour now have realized, we cannot wait for more deaths and more targeted violence from fascists to take these things seriously. For every Heather Heyer, there are countless black, indigenous, and other people of colour, queer and trans people, disabled people, and others who too have and will continue to suffer if we remain aloof. If our predecessors on the baseball fields of Christie Pitts figured this out, so too must we.

We Need To Accept That Some Resistance Requires Violence

While liberals blanche at some of the tactics of resistance used in Charlottesville, Quebec City, and elsewhere, we can look back at our successes to see that not all resistance will be calm and orderly affairs. The Christie Pitts Uprising was, essentially, a street battle for control between fascists and community defenders. This was not a dialogue. This is not seen today as an all-sides-are-equal fight. Instead, we commemorate the Uprising because it serves as a reminder of the power of community defence and its need in our city. The Uprising broke the wider silence against these clubs—and while the hydra of fascism rose again in Toronto and elsewhere—the safety of those communities were preserved and wider conversations began across the city.

The Uprising allowed for other tactics to have effect which would have otherwise been lost or blunted in an indifferent political structure. Contrast this to the often narrative that such tactics undermine others—instead, they move (and moved then) in concert to greater goals to disrupting fascist growth in the city.

We Need To Connect Anti-Fascism To Everyday Struggle

The Swastika Club and fascists of the era were not mythical figures. They were other people in the neighbourhood, playing in the local baseball league. They did not creep in like some shadow over the city, but were themselves part of our existing fabric. Too often we forget that fascists of all eras are still people—still part of the societies we live in and grow within those very spaces while violent and vile. They are not from some other place or from beyond our sight. Toronto, like any place, can be home to their rotten ideology.

But just as vile fascism is part of the fabric of the societies we live within, so too is resistance within ourselves. Our everyday resistance is also not in isolation from our anti-fascist action. For those in Christie Pitts on the 16th of August, fascist violence and provocation was a violent, extreme extension of the marginalization brought about on the Jewish and Italian communities. Fascists could grow then because they fed on existing violence in our city against these communities. Today, fascists feed on Islamophobia, transphobia, and anti-Semitism in Toronto to recruit and grow their ranks. They feed on poverty and systemic economic inequality—in both their targeting of rich and working class folks. We cannot truly beat back the fascists without grounding in these struggles. We cannot work in a vacuum, as the fascist certainly does not.

The working class solidarity shown by communities during the Uprising is a model here. These people did not have to imagine the jackboots of the Nazi Party—even as their communities had faced it—for they already faced marginalization here at home. Together, they fought for their communities, their freedom, and to push back against the forces which allowed for fascists to grow in the first place. We too must take this tact and view our work more seriously and connectedly.

While people debate endlessly over the merits of particular tactics today in Charlottesville, Quebec City, and elsewhere, do not forget the lessons from Christie Pitts—that we can resist and protect our communities, while building deep and lasting bonds together.

O. Berkman, a pseudonym, is a Toronto-based researcher on history in Southern Ontario and anti-fascist resistance in the region. They would encourage readers to also check out the original sources for this piece, particularly original reporting done in 1933—much of which is available through the Toronto Public Library.