Filed under: Critique, The State, White Supremacy

This piece was written and edited by a loose BIPOC collective out of the Bay Area and levels a critique of modern identity politics which traces new lines of revolt and recuperation following the George Floyd rebellion.

by Brazo & Turner

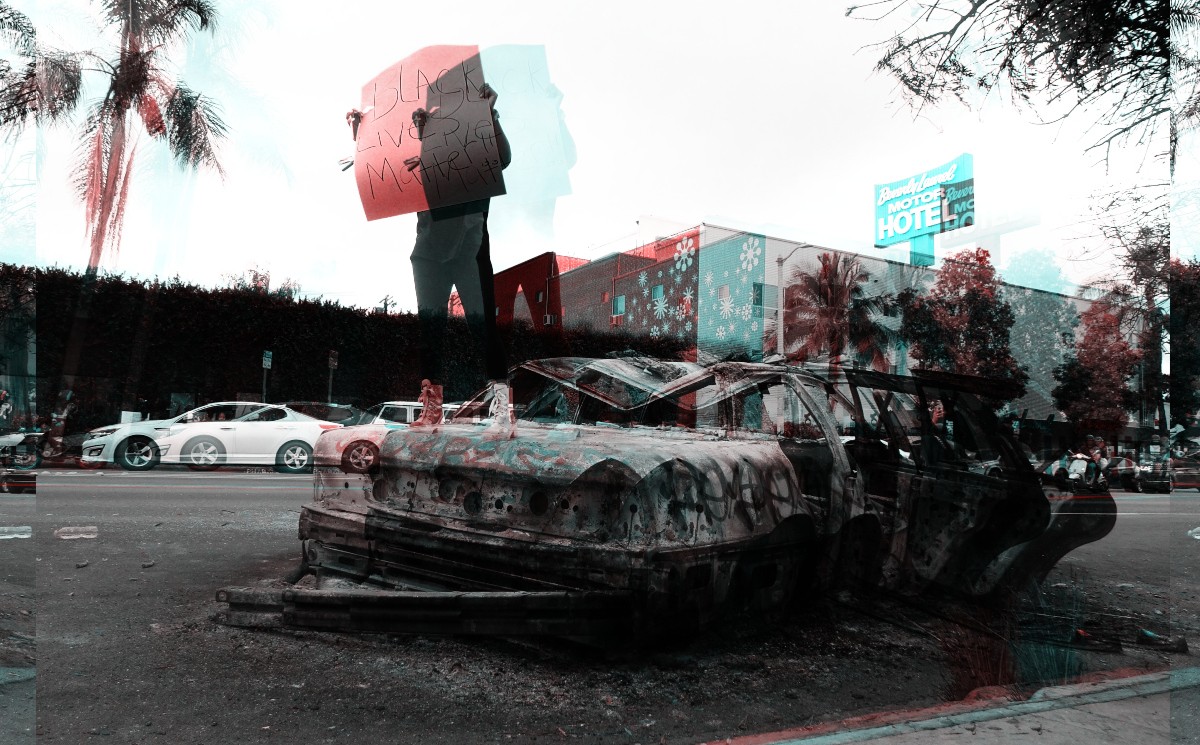

Since the beginning of the George Floyd rebellion on May 26th, 2020 we have seen an enormous wave of national and international support for the uprising, even in the face of millions of dollars lost to looting, expropriations, and property destruction around the US. This uprising has been marked by the 3rd police precinct in Minneapolis being turned to ash, the construction of the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone in Seattle, and the burning of the Department of Corrections building in Kenosha after yet another shooting of an unarmed black man named Jacob Blake. The repressive apparatus of the State has returned the volley in this social war with thousands of protesters of all different stripes facing long prison sentences, and of course, the federal occupation of the city of Portland.

There are a myriad of different ways one could choose to analyze, critique, and understand what has happen in the past few months, for us it is important to choose a method that reflects our politics. Unlike historical, sociological or Marxist texts that use the scientific method in order to generalize a “grand narrative” of past events, we hope to create one story among many for use in the liberatory project. We attempt to do this by using specific examples from peoples subjective experiences both past and present, as well as more abstract analytical tools that are specific to the US context. Since rebellions around the world are on the rise it has been a trend to attempt to draw translatable conclusions from Hong Kong to Argentina, from Lebanon to Greece, and while there are some generalizable characteristics, they are, by and large only tactical. Each rebellion has its own particulars that make it blossom. Routine generalization for sake of scientific accuracy masks more than it reveals, and is part of the academic imperial and colonial project.

One monumental point for understanding the specificity of the US black liberation struggle and race relations in general is articulated by Hannah Arendt when she says, “The US is not a nation…This country is united neither by heritage, nor by memory, nor by soil, nor by language, nor by origin.” The early slave ships and native concentration camps are a case in point. Arendt was a Jew in Germany during the rise of Hitler and after being arrested by the Gestapo fled Germany and eventually ended up in the US. Her experience helped shape her understanding of the US and its statecraft being significantly different than other European countries which had some type of commonality before the formation of the State itself. The criterion for citizenry in the US is the simple consent to the constitution. We are constantly reminded by the State of the sacredness of this scrap of paper.

The US is a country “ruled by law, not by men” and this important dynamic illustrates both the liberal and conservative obsession with law and order, it is the only thing holding together American society. For the US, the State is the unifier and is the commonality. This order is one shaped by capital’s necessary exploitation of labor and the racial hierarchy it requires.

The war the US government has waged on different groups: indigenous people against State sponsored genocide, or slaves and abolitionists against slavery (culminating in the Civil War) has never ended, with the continued seizure of Native lands for extraction projects like Standing Rock, or the continuation of slave labor with special clauses in the 13th amendment, allowing for slave labor as long as the person is classified as a “criminal.” Thus the modern slave catchers known as the police continue their raids in our communities, and are met with our resistance. What we have witnessed during this rebellion is not new, but the residual conflicts that make up the fabric of US society. Furthermore we can see that in order to permanently rupture this relationship of domination and violence we must attack the state and allow for our own more liberatory relationships to take its place.

While spearheaded by a black avant-garde, this largely multi-ethnic rebellion managed to spontaneously overcome codified racial divisions. The containment of the revolt aims at reinstating these rigid lines of separation and policing their boundaries. “

– Idris Robinson “How it Might be Done?

Of the many counter-insurgency tactics used to shut down the uprisings, the increased policing of identity during demonstrations has been an important method used to pacify our movements towards liberal and reformist ends. Motivated by white guilt and identity authoritarianism, performative activists demanded “white people to the frontline,” as if their privilege can stop rubber bullets, or the more nullifying demands of self-appointed black leadership to only use non-violent tactics to accomplish all political goals. The liberal post civil rights era mythology has constructed an archetype of the authentic political actor. This actor is modeled after the most palatable people for the State, non-violent resisters who seek reform. Henry David Thoreau and Dr. Martin Luther King in the US context are the back bone of this modeled form of acceptable political action. In Thoreau’s words, “Under a government which imprisons any unjustly…the true place for a just man is also a prison.” Both Thoreau and King in practicing no-violent civil disobedience accept the logic of the State and it’s prisons. Identity politics has muddled the water between identifying with a systematically oppressed group, and prescribing what actions should be taken to end that oppression. There is no inherent relationship between who you are, and what you do, this is an act of will.

The current use of identity politics is policing identity (who can and cannot act based on who they are) and by extension police what acceptable political action looks like. This explains why those who act outside those bounds of behavior are labeled “white” or “outside agitators,” regardless of who is actually carrying out these actions. Raoul Vaneigem succinctly observed “the role is a model form of behavior…Access to roles is ensured by identification. The need to identify is more important to Power’s stability than the models identified with.” The policing of identity is a crucial part of reifying roles within power.

Before Oakland’s first night of major upheaval on May 29th, the self appointed black leader of Oakland, Cat Brooks (who is actually from Las Vegas) denounced the protest via Twitter before the demonstration even happened:

Let me be CLEAR: white people DON’T get to use Black pain to justify living out your riot fantasies. What’s happening in Minneapolis is BLACK LEAD Rebellion. That can’t be manufactured and we ain’t going back in time in Oakland. Please don’t make me come off this mountain.

These sentiments have been spread by authoritarians and recuperative state leaders during the rebellion in every city in the US. Had Cat been on the ground and not “on the mountain” the first day of the rebellion, she would have witnessed what we have been seeing on the street since the Oscar Grant rebellion. A multi-ethnic multitude coming together like a match and gasoline, the college student and the project resident standing side by side overcoming spontaneously, all divisions imposed on them by society, to light a fire that never goes out.

The following night after heavy rioting the leaders tried to reinstate peace and control by calling for a sit in demonstration at 14th and Broadway. Thousands flooded the streets and sat in an intersection for over an hour listening to speeches and eventually went home. The correct order had been restored.

While it is true that the “multi-ethnic rebellion managed to spontaneously overcome codified racial divisions” during the first days of the rebellion, it is worth exploring further, the types of insurgent abolitionist relationships in US history to give us examples on how it might be done, and what long term multi-ethnic rebellion is capable of. The last movement for abolition in the US escalated into a civil war, with former slaves and abolitionists leading the charge. This is best personified in the relationship between Harriet Tubman and John Brown. Meeting for the 1st time on April 7th 1858 to plan the raid on Harpers Ferry, which sought to take over a West Virginian military arsenal in order to arm slaves in the south to start a slave insurrection. Their first encounter noted by historian Phillip Thomas Tucker is exemplary “important on a number of different levels was the fact that the expertise of the black radical world – in the form of Harriet Tubman in this case – was coming together at the right time and the right place with the radical white world (leading Northern abolitionists as best personified by John Brown).”

By the time the two had met, they had already known each other through reputation, Harriet Tubman having freed over 300 slaves through the underground railroad, and John Brown at that time known for freeing slaves in Missouri with use of guerrilla tactics and most notably the murder of 5 pro-slavery settlers in the Kansas Territory. Their relationship created “a deep bond…one of the most unique relationships in all America consisting of two remarkable individuals… A white man and a black women were thoroughly united as one in a single spirit in regard to their holy war and mission, which overcame racial and gender differences in an entirely unique and symbiotic relationship that was extremely rare in America in 1858.” Without both of these individuals the abolition of slavery in the US would not have been possible, both black and white together for the same goal: abolition.

A more contemporary example of multi-ethnic rebellion can be drawn from the modern plantation system, the prison. In California at the Pelican Bay state prison in 2011, the Short-Corridor collective was formed, and 3 years later initiated the California state prison hunger strike, which included 29,000 inmates throughout CA prisons:

The creators of the Corridor Collective and also the leaders behind the strike were Todd Ashker, Arturo Castellanos, Ronnie Dewberry, and Antonio Guillen. Each of the leaders were prisoners within the Pelican Bay Prison SHU (Security Housing Unit), with Ashker being a member of the Aryan Brotherhood, Castellanos belonging to the LA street gang Florencia 13, Dewberry being in the Black Guerrilla Family, and Guillen in the Nuestra Familia gang.

The strike sought “an end to long-term solitary confinement along with group punishments, better and more nutritious food, along with ending policies surrounding the identification and treatment of suspected gang members.” In the depths of some of the harshest conditions of oppression in the modern world, these prisoners found solidarity as the only weapon between vastly different groups in order to strike back against the prison system. One means of accomplishing such a goal was printed in their statement Agreement to End Hostilities:

Therefore, beginning on October 10, 2012, all hostilities between our racial groups… in SHU, Ad-Seg, General Population, and County Jails, will officially cease. This means that from this date on, all racial group hostilities need to be at an end… and if personal issues arise between individuals, people need to do all they can to exhaust all diplomatic means to settle such disputes; do not allow personal, individual issues to escalate into racial group issues!

As revolutionaries and abolitionists we must take the example from these brave freedom fighters. The racial divisions imposed in the prison system are exemplary of the divisions throughout society. The mechanisms of repression and division are not as clear on the outside of a cell.

A grand juror from the Breonna Taylor case has come forward to say jurors were ‘never given the opportunity’ to deliberate homicide charges. Contrast that with AG Daniel Cameron’s RNC speech pic.twitter.com/6inPJnP20i

— NowThis (@nowthisnews) October 20, 2020

At this juncture we must return our attention to two examples that help us understand and resist the mechanisms of hierarchical division that are entrenched in the language of identity politics. After the Grand Jury decision was announced by Kentucky Attorney General Daniel Cameron in the case of Breonna Taylor, organizer and activist Tamika Mallory made a statement about the verdict that points to a nuance in identity politics that is rarely spoken about, she states:

As I lay and cried for and hurt for Tamika Palmer, for Breonna Taylor, for Kenny Walker…I thought about him (Daniel Cameron) saying he is a black man – I thought about the ships that went into Fort Monroe, and Jamestown with our people on them over 400 years ago, and how there were also black men on those ships that were responsible for bringing our people over here. Daniel Cameron is no different than the sellouts who sold our people into slavery and helped white men capture our people. You were used by the system to harm your own black mama, we have no respect for you, no respect for your black skin, because all of our skin folk, are not our kinfolk.

Tamika shows us the historical continuity between past and present, between the black “sellouts” of the slave ships, and the Black Attorney General who is complicit in the murder of Breonna Taylor. Tamika temporarily throws off the lens of identity politics to view the actions of Daniel Cameron as they stand, and for who they serve, and revokes his ability to use his identity to hide behind his cowardice. It is Cameron’s actions, not his identity that make him a servant for white supremacy.

Letter to Michael Reinoehl from Idris Robinson: “The sad fact of the matter is that everyone on our side claims to be waiting for the next John Brown, but when he finally appears before us, we instead line up to unanimously reject him.” https://t.co/wUoBLmgIvr

— Wendy Trevino (@prolpo) October 24, 2020

Armed white supremacist groups have been making more appearances enacting or threatening the use of violence all of over the US in response to the uprisings for black liberation. Right-wing protestors have been firing into crowds of BLM protestors, Alan Swinney of the Proud Boys was seen pointing a gun a protestors, and 17 year old white supremacist Kyle Rittenhouse shot three peopled and killed two in a march in Kenosha, Wisconsin. In Portland, Oregon after several weeks of protests after the murder of George Floyd, on August 29, 2020 in an act of revolutionary solidarity, antifascist Michael shot and killed an armed white supremacist Aaron J. Danielson. Reinhold conducted an interview about the killing on VICE. He admits killing Danielson as an act of self-defense and in the interview said, “I could have sat there and watched them kill a friend of mine of color. But I wasn’t going to do that.” A week later on September 3rd, Reinoehl was assassinated by the FBI and US Marshals. Both examples point to the abandonment of the use of pure identity as a determinant for action. Cameron, the Attorney General who should have supported Breonna Taylor as a black man, chose to serve white supremacy; Michael Reinoehl who is a beneficiary of white privilege, scarified his life to stand in solidarity with people of color.

In identity politics’ quest to find the most oppressed, we sort through the different identity formations looking for the most authentic actor for change. But as Frantz Fannon the Algerian writer on decolonization has pointed out; decolonization and liberation are processes, whereby acting defines and creates a new human being:

Decolonization never takes place unnoticed, for it influences individuals and modifies them fundamentally…It brings a natural rhythm into existence, introduced by new men, and with it a new language and a new humanity.

This understanding is of the utmost importance and simultaneously points to the shortcomings of identity based politics. Far from its point of origin in black feminism in late 1970’s, US identity politics now focuses mainly on individual behavior and attitudes as reflections of social privilege and oppression. Elevating individual behaviors as the only representations of oppression, signifies a retreat from politics and the material conditions of oppression itself. Arguing over ‘who is allowed to burn the police station’ before lighting a single match, many activists, non-profits, NGO’s and politicians make a living on continuously pronouncing that their particular brand of action is authentic and effective, when it is anything but this, to do this they rely heavily on representation and mediation of our rightful hatred of these system.

The theories of identity politics suit us in understanding the hegemonic racial hierarchy and identity, but to make the error of allowing them to essentialize us and define us in our totality simply reinforces power, by denying new constructions and formations of identity and solidarity through struggle. We must begin to judge one another based on what we do, and not solely on who we are perceived to be. If we believe in radical social change we must also believe individuals are capable of radical change as well. To recognize that the actions taken in the streets in the last few months have already fundamentally changed the people who participated in the uprising. What is required of us now is the ability to make those changes legible to ourselves by opening up our understandings of who the participants are in this struggle for collective liberation.