Filed under: Analysis, Disability and Ableism, Featured, White Supremacy

In this critical analysis, the author examines how prison and police abolition intersect with madness and disability, and calls for increased movement solidarity in the fight against racial capitalism.

In 2020, police abolition erupted into popular discourse following the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Tony McDade and others. With one out of four U.S. prison inmates testing positive for COVID-19 in some facilities, calls for prison abolition have also attained a new prominence. We want to abolish these systems of violence – but what would that mean for the psych ward?

This essay explores possible responses to that question in two parts. This is part one, which focuses on the intersections between abolition, madness and disability. Part two will focus on the ways we can fight for mad and disabled communities while creating an abolitionist future.

ABCs of Abolition

When we call for abolition, it’s because we believe another world is possible. A world where black, brown, trans and poor communities are not executed by the state or held in cages. As abolitionists, we reject the fantasy that “public safety” depends upon state surveillance and mass incarceration. We call for abolition because prisons and police are rotten at the core – the issue isn’t a few “bad apples,” it’s the entire system.

In an era of racial reckoning, we can’t condemn the white supremacy of the past without acknowledging its ongoing role in today’s prisons and policing. This white supremacy is apparent at Louisiana State Penitentiary, also known as Angola, which functioned as a plantation prior to becoming a prison. As the largest maximum-security prison in the United States, Angola still maintains a massive “farm,” where inmates are forced to pick cotton and other crops.

White supremacy is also written into the Major Crimes Act, which attempts to deny Indigenous peoples’ sovereignty over their own communities and land. The origins of policing are inextricably linked to slave patrols and the Ku Klux Klan, and contemporary police shootings are a continuation of lynching practices and the genocide against Indigenous communities.

Since prisons and police are rooted in the same racial capitalism that created slavery – and colonialism – today’s abolition movements continue the work of 18th and 19th century abolitionists. These revolutionaries ask us not simply to end prisons and policing but to (re)discover new ways of living together in community, without state violence. Critical Resistance, the prison abolition group founded by Angela Davis, Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Rose Braz, and others, describes their work as a manifold process:

Abolition isn’t just about getting rid of buildings full of cages. It’s also about undoing the society we live in because the [Prison Industrial Complex] both feeds on and maintains oppression and inequalities… An abolitionist vision means that we must build models today that can represent how we want to live in the future.

Prisoner solidarity and practices like transformative justice are a clear part of abolition. It’s less clear, however, how we bring an abolitionist vision to disabled communities or to people’s lived experiences of madness. People say, “Police shouldn’t respond to non-emergency 911 calls. ‘Mentally ill’ people shouldn’t be jailed for petty crimes. We need better mental health.” But what does this actually mean?

This question matters because mad and disabled communities are overwhelming subjected to incarceration and state violence, especially among poor and houseless communities, trans and nonbinary individuals, and communities of color. To understand what’s at stake here, we might start by examining how racial capitalism currently relates to madness and disability.

Madness Under Racial Capitalism

When a person is perceived as being “mad” – that is to say, when a person is deemed “unstable,” “aggressive” or “in crisis” – the state responds with violence. After police attacked Elijah McClain on the streets of Aurora, Colorado, paramedics forcibly injected him with a lethal dose of ketamine. Chemical restraint was justified because McClain, a Black man, was exhibiting symptoms of “excited delirium.” In order words, McClain was executed for listening to music and dancing while walking down the street.

This murderous collaboration between paramedics and police typifies the relationship between “mental health providers,” their (para)medical proxies, and the state. When approaching anyone deemed “mentally ill,” the state responds with tools of incarceration, including coercion, confinement, and violence. This is because the mental health system operates on carceral logic. Psych holds and forced hospitalization are forms of incarceration that rarely require a crime or conviction. If you protest against your incarceration this is understood as resistance to treatment, and such resistance, which the doctors call anogosonia, is evidence of your “illness.” For anyone unfamiliar with psych wards and their rhetoric, poet Anita D’s piece “And the Psych Ward Says” is a powerful testimony of what it means to be involuntary committed.

Numerous social movements have arisen to fight against psychiatric oppression, with militant groups historically describing themselves as anti-psychiatry, psychiatric survivors, ex-patients, and human rights activists. These movements don’t only fight against forced hospitalization, but question the very narratives of psychiatric treatment.

We scrutinize why a group like the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) frames itself as a “grassroots” group while receiving up to 75% of their funding from pharmaceutical companies. As Sera Davidow writes, “We have to remember this: NAMI is a lobbying organization.” While less known as household names, lobbying groups like the Mental Health America (MHA) and the Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance (DBSA) are equally complicit in manipulating public discourses to mimic corporate agendas.

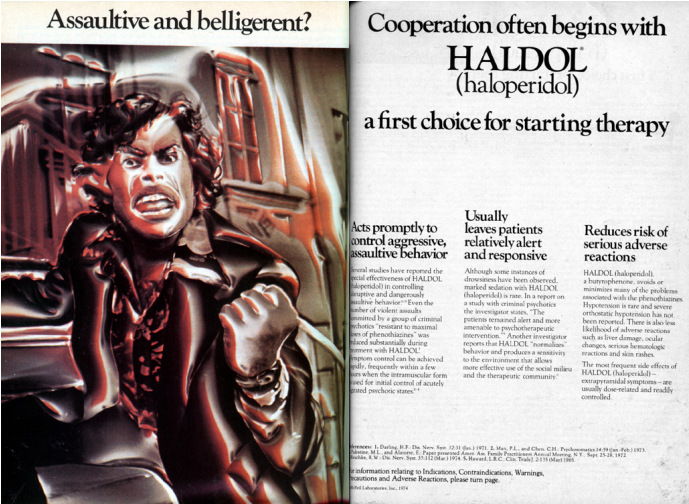

Image shows a 1974 advertisement from the Archives of General Psychiatry, which depicts an urban Black man in a leather jacket. The headline reads “Assaultive and belligerent?,” and the next page reads, “Cooperation often begins with Haldol,” followed by details about the antipsychotic medication.”

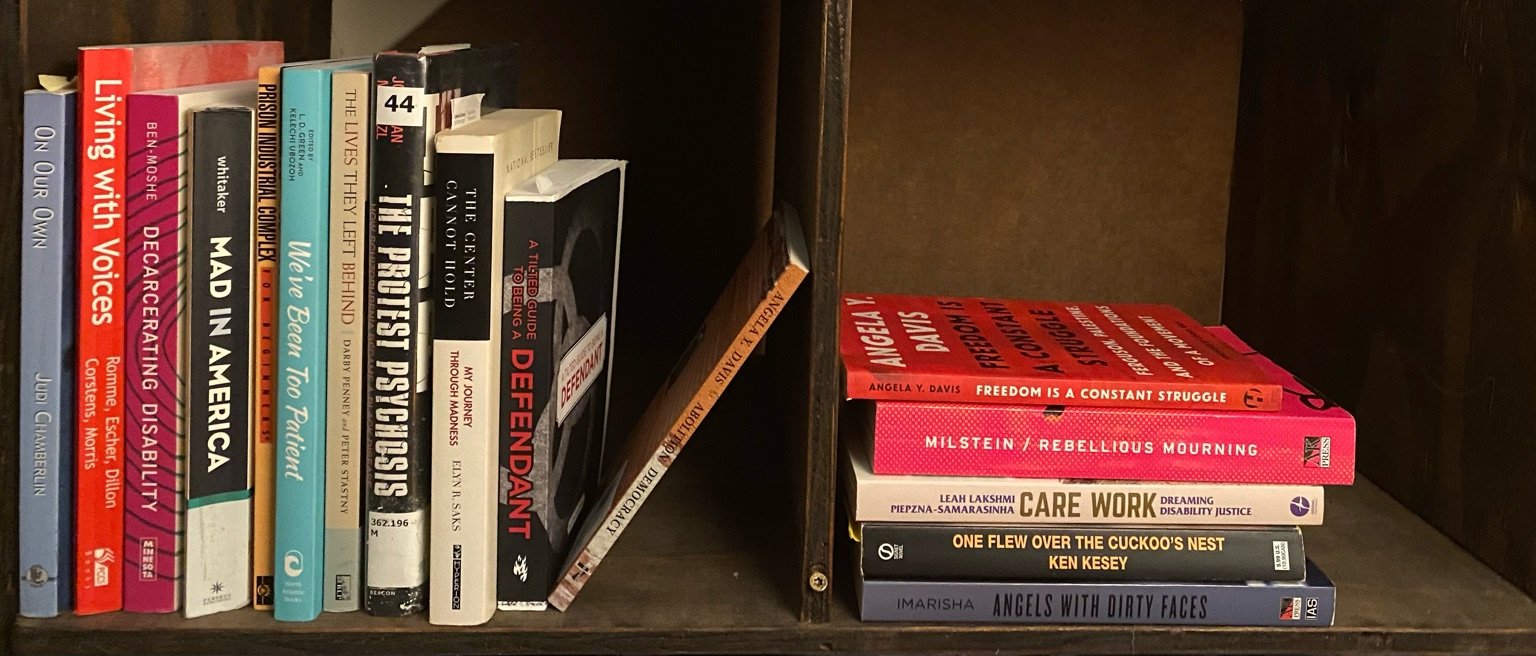

Books like Mad in America by Robert Whitaker and Psychiatry Under the Influence by Whitaker and Lisa Cosgrove further reveal how the bio-medical nature of “mental illness” is actually a capitalist ideology driven by the pharmaceutical industry and rooted in eugenics. Protest Psychosis by Jonathan Metzl highlights the racialized underpinning of these histories, with a focus on “schizophrenia” and its shifting symptomatology.

In the 1950s, writes Metzl, the diagnosis was a tool of white patriarchy primarily given to disobedient housewives. Following the re-writing of diagnostic criteria in 1968, schizophrenia became a “disease” disproportionately diagnosed among Black men, which provided doctors a means to pathologize and incarcerate Black political dissidents – by labelling angry, anti-state Black men as “paranoid” and “delusional” – during the era of Black power.

Psychiatric oppression is also central to colonization. In her chronicle of the Hiawatha Insane Asylum for Indians, Pemima Yellow Bird (Mandan, Hidasta, and Arikara Nation) describes “some of the darkest times of our holocaust, tangled in a horrific web of greed, political opportunism, and racist oppression.” In her cries of resistance, Yellow Bird declares, “never again will one of our people suffer at the hands of an omnipotent, destructive and corrupt government, or from the criminally misguided acts of the mental health industry in this country.”

These brutal histories are marginalized in the United States but thanks to the work of activists like Celia Brown and MindFreedom International, even the United Nations Human Rights Council recognizes the injustices of our systems. “Mental health systems worldwide are dominated by a reductionist biomedical model that uses medicalization to justify coercion as a systemic practice,” UN Special Rapporteur Dainius Pūras wrote in a recent report. In their failure to understand the roots causes of human distress, mental health systems render “diverse human responses to harmful underlying and social determinants (such as inequalities, discrimination and violence) as ‘disorders’ that need treatment.” This is one of many reasons why forced hospitalization actually increases the likelihood that a person will attempt suicide.

When we consider the horrors of the mental health industry, we should ask ourselves the same questions we ask of prisons and police. Can the system be “reformed,” or is it rotten to the core? For many of us organizing against psychiatric oppression, the answer is clear.

Diagnosis, Disability and State Violence

As a tool of psychiatric oppression, diagnosis itself can be understood as a precursor to violence. That is to say, labeling a person with “schizophrenia” or describing their behavior as “excited delirium” provides the future or immediate justification of state violence. But lack of diagnosis can also derive from systems of oppression. For instance, Lydia X. Z. Brown has highlighted the racist implications of under-diagnosing learning and developmental disabilities among youth of color.

Mad and disabled communities often have different ideas about diagnosis, which are not easily reconcilable. As we imagine what abolitionist relationships to diagnosis could be, it is important to center the perspectives of those most impacted by diagnosis (or lack thereof), including people who experience voices and visions, trans and nonbinary individuals, poor folks who depend on disability benefits, people with critical access needs, and anyone with lived experience of incarceration and institutionalization, including BIPOC youth who receive select diagnoses in the school-to-prison pipeline.

Like anyone deemed mad, disabled people are also hunted by the state, especially in communities of color and among poor and trans communities. Mad and disabled communities are disproportionately locked up in jails and prisons, and as scholar Ben Liat-Moshe writes in Decarcerating Disability, these systems actually create madness and disability.

SOURCE: http://disabilityhistory.org

In their statement on police violence, the disability justice collective Sins Invalid reports that more than half of the people murdered by police are disabled, and state violence only continues in prisons and detention centers:

We witness the horror of a deadly chokehold placed on Eric Garner, a Black man with multiple disabilities, by the NYPD. Our hearts break for Kayla Moore, a fat Black schizophrenic trans woman suffocated to death by police in her home in Berkeley, after her friends called 911 for help… We are outraged by the in-custody death of Lakota 24 year-old mother of two, Sarah Lee Circle Bear, who was refused medical care… We embrace the memories of Victoria Arellano, an under-documented Latinx trans woman, and Johana Medina, an asylum-seeking Latinx trans woman, who were both living with AIDS, and died in ICE facilities as a result of being denied medical care. We feel devastation with the family of Natasha McKenna, who cried ‘You promised you wouldn’t kill me!’ just before being tasered to death by half a dozen guards in a Virginia jail. We stand with Lashonn White, a Deaf queer Black woman who was running toward police for safety, and was instead tased by police and jailed for three days without access to an interpreter.

Despite the overlap between disability and other struggles for justice, many comrades are still focused on narrow, single-issue fights. This is articulated by disability justice organizers, who note that traditional disability rights communities often perpetuate racism, while racial justice organizers lack an analysis around disability.

“When a Black Disabled person is killed by the state, media and prominent racial justice activists usually report that a Black person was killed by the police,” writes Talila Lewis, a founding member of the Harriet Tubman Collective. “Contemporaneous reports from disability rights communities regarding the very same individual,” continues Lewis, “usually emphasize that a Disabled or Deaf individual was killed by the police – with not one word about that person’s race, ethnicity or indigenous roots.” Even disability rights/justice and mad communities often operate in parallel to one another, rather than our communities working together.

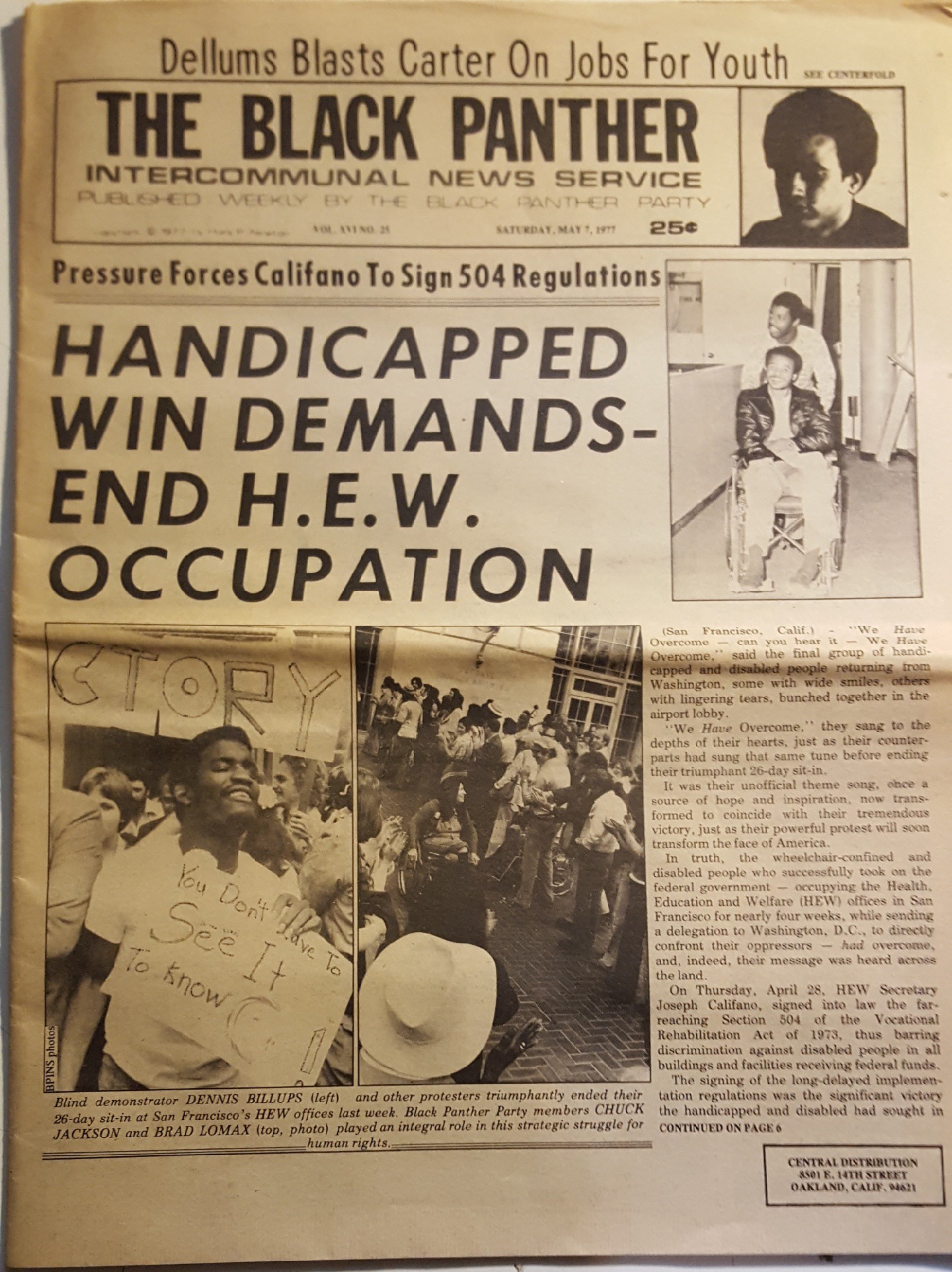

Mad communities has also re-enforced white patriarchal norms, as was evidenced by a recent statement on transmisogny in the movement. Yet it is important to acknowledge that intersectionality in our movements is not new – for instance, unions and the Black Panther Party were critical allies during the 1977 federal building takeovers of the 504 Sit-in. The current predominance of white, cisgendered leadership in mad and disabled communities should be understood as a result of ongoing movement politics – because leaders are “chosen” only after a lot of other people have been marginalized, ignored or forgotten. Perhaps it is through abolitionist analysis that mad and disabled communities will understand our own internal systems of dominance and erasure more clearly.

Movement Solidarity for Future Worlds

If we are to succeed in our struggles for liberation, we must build cross-movement solidarity. Developing strong alliances between existing abolitionists and mad and disabled communities will significantly expand our core of frontline activists, and further developing our base of committed supporters.

Cross-movement solidarity isn’t simply a good organizing strategy, it’s a necessity for survival. Mad and disabled communities are being incarcerated and murdered by the same institutions that target Black, trans and nonbinary, poor, Indigenous, youth of color, Latinx communities, and everyone else deemed expendable under racial capitalism. Police and prison abolitionist should come together with mad and disabled communities because we share common enemies, and interconnected goals.

Abolitionist histories offer essential insights into the so-called nature of progress, as it occurs under racial capitalism. Just as the convict leasing system arose in the post-Civil War era, today’s abolitionists must remain vigilant against “alternatives to incarceration,” including house arrest, electronic monitoring, and community assisted “treatment” programs. In today’s fight against false alternatives, mad and disabled communities carry profound wisdom – because we know that the current mental health system is not an acceptable “alternative” to mass incarceration or state violence. If abolitionists simply replace prison bars with hospital walls – or give social workers bullet proof vests and arm paramedics with lethal doses of ketamine – this doesn’t change anything.

The struggle requires incremental changes because police, prisons, and psych wards aren’t going to disappear overnight. This is why prison abolitionists talk about “non-reformist reforms,” which lay the foundation of our revolution. But where and how do these changes occur, in actuality? This is an open-ended question, and one that requires acts of imagination. We are, after all, dreaming new worlds (back) into existence.

Part two of this essay will explore the future worlds that mad and disabled communities are building, and the ways we can work together toward abolition. If you are interested in madness, disability, and abolition and would like to say hello, please write to madresistance@protonmail.com.

photo: Bianca Berg via Unsplash