Filed under: Anarchist Movement, Featured, History, Interviews, Mexico, The State

On November 21, 2022, one hundred years after his death, anarchists gathered at the tomb of Ricardo Flores Magón in Mexico City, where clashes ensued with members of the Regional Confederation of Mexican Workers (CROM), leaving several compañerxs injured. In December, IGD contributor Scott Campbell interviewed Jaime, one of the anarchists present that day. The interview covers not only the events of November 21, but the life and legacy of Ricardo Flores Magón, the State’s attempts to recuperate his memory, and more.

Lee esta entrevista en español aquí.

IGD: How would you like to introduce yourself?

My name is Jaime. I’ll be speaking on behalf of those who took part in the action [on November 21], but which is not a collective.

IGD: Can you speak to the importance of Ricardo Flores Magón? Who was he, what is the significance of his work and legacy?

Ricardo Flores Magón was an anarchist, born in Eloxochitlán de Flores Magón, Oaxaca, in 1873, and who, at a very early age, became aware of the political and economic situation in Mexico at that time. He had contact with anarchist and libertarian ideas; he read Bakunin, Kropotkin, and Malatesta. As well, his Indigenous Mazatec origin and the practices of Indigenous communities, such as solidarity and mutual aid, had a large influence on the formation of his thought and ideology. From a very young age, he began to fight, to combat, to organize against the dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz, which brought him persecution and repression. He, along with his brothers Jesús and Enrique, and people such as Juan Sarabia and others, founded a newspaper in 1900, called Regeneración, through the distribution of which a network of liberal groups was created that over the years evolved into an insurrectional network.

In 1905, the Regeneración group left Mexico for exile in the United States. By then, Ricardo Flores Magón and others had been imprisoned, had been persecuted, the Regeneración printing press had been confiscated, so they considered it unsustainable to continue the struggle in Mexico and went to the United States and settled in California. In 1905, they created the Organizing Junta of the Mexican Liberal Party (PLM), which is the political organization that guided or gave form to this organizational network. By 1906, it became an insurrectional network that encouraged and fomented armed uprisings in different parts of the country, primarily in Veracruz, in Chihuahua, in Acayucan, in Las Vacas, and so on. That is to say, Ricardo Flores Magón and others, such as Librado Rivera, Margarita Ortega, Jacinto Palomares, in short, a series of individuals, began to fight the dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz, but not to put an end to it and just install someone else as president.

Within the Mexican Liberal Party there were different tendencies, one obviously much more liberal or moderate, that sought a political revolution, that is, a revolution just in those terms: to remove Porfirio Díaz from power and to hold free elections so that someone else may ascend to the presidency. But on the other hand, there was also a more radical tendency, represented or inspired by anarchism, which sought not a political but a social revolution that would put an end not only to the dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz but also to capitalism and the principle of authority.

This debate caused a rupture within the Mexican Liberal Party; the moderates left the PLM, leaving only the anarchists, who kept the name “liberal.” This corresponded to a strategic question documented in texts by Ricardo Flores Magón where he says that, for strategic reasons, so as not to scare or alert others, they continued calling themselves liberals, although their objectives were clearly anarchist and anti-authoritarian.

So, in 1906 and 1908, there were insurrectional attempts, armed uprisings, fomented by this network. There is much talk, for example, of the strikes at Cananea and Río Blanco as being precursors of the Mexican Revolution, and it is even said that they were inspired or influenced by the PLM. The truth is that although there were people from the PLM involved in these two movements, it was circumstantially. If there were movements before 1910 inspired and fomented by the PLM it was the Acayucan rebellion, the insurrection of Las Vacas, of Viesca, that had the very clear objective of establishing libertarian communism. The strikes at Río Blanco and Cananea certainly are important within the history of the labor movement and the history of Mexico, but they had very concrete demands the corresponded to the conditions of each site, though clearly they occurred within the context of the Díaz dictatorship and U.S. interests.

But where I am going with this is that a narrative has been created of Ricardo Flores Magón as the initiator of the Mexican Revolution. This revolution that, in 1911, ends the dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz and starts a factional conflict that ends in 1917, with the arrival of Venustiano Carranza to power and the birth of a post-revolutionary state that then begins to recuperate figures for its pantheon. It recuperates Emiliano Zapata as well as Venustiano Carranza, Francisco Villa as well as Felipe Ángeles. And in this recuperation of figures for the post-revolutionary pantheon and the nascent modern Mexican nation-state, Ricardo Flores Magón is recuperated as just that, the ideologue, the forerunner of the revolution and nothing more.

The official history says that Flores Magón founded a newspaper and began the struggle against Porfirio Díaz, but that in 1910, Francisco Madero came out of nowhere and issued the call to arms. So, it positions Magón as simply an intellectual, a journalist who wrote articles and criticized Porfirio Díaz. But what is not talked about is that Magón was much more than that. Magón and the Mexican Liberal Party, as I said, fomented a social revolution that they obviously lost. In short, the importance of Magón goes beyond the fact that he was a journalist or inspirer of the revolution.

Magonistas in Tijuana in 1911.

Magón never stopped fighting, and not just him. He was part of a much larger group, of a much more extensive network, that even as of 1914, for example, when the armed conflict in Mexico had entered a more advanced stage, there was still activity by the anarchist groups of the PLM. For the official history, this is irrelevant, it doesn’t speak of this, or when it speaks of it, it does so in order to disqualify or recuperate. An example of this recuperation is that, just recently, on November 21, the 100th anniversary [of Magón’s death], in an official act in the National Palace, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, the president of Mexico, paid homage to Ricardo Flores Magón, saying that he was an anarchist, but one of the good anarchists.

So, I think that the importance of Magón goes beyond having been a journalist, having been an initiator of the revolution. His importance, at least for the history of anarchism and the anarchist movement, is not just in Mexico but at the world level, because little is said about that, about the internationalist dimension of the PLM struggle. The PLM weaved networks, connections, with anarchist groups in the United States, with Italian anarchist groups based in the United States, it maintained relations with Russian anarchists such as Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman, with Luigi Galleani. It also maintained relationships with anarchist groups in Argentina, Colombia, Cuba, Spain, France, in a vision of struggle that was not only about removing Madero or whoever was in power at that moment in Mexico, but of a revolution on a much larger scale at the international level.

I believe that Magón’s importance for anarchism in Mexico and the world is that, and that his dedication to this struggle, his passion for freedom, was so great that until the last day of his life, until his last breath, he did not abandon it – something that precisely cost him his life. In 1918, he was imprisoned in the United States for a proclamation he wrote and that the U.S. government used as a pretext for jailing him again for violating laws about the war and so on. He was imprisoned together with his eternal compañero in the struggle, Librado Rivera. And from this imprisonment, Ricardo Flores Magón would not emerge alive. In 1922, he was killed in his cell, he was killed by another prisoner on the orders of the warden of the prison.

He was offered the possibility of being released, his health was already very poor, he was practically blind, and his health had deteriorated after having been in prison several times for years. He was offered his freedom in exchange for writing a letter asking for forgiveness and repenting for his actions, to which he replied that he would rather die in prison, go blind, than ask for forgiveness. So, I think it is just that passion, it never left him, and beyond putting him on an altar as an idol or seeing him as a martyr, what we see is an indomitable force and an enormous passion for freedom, and I think therein lies the importance of Ricardo Flores Magón.

IGD: You touched on this a little, but how has the State attempted to appropriate Magón for its own purposes? What have been the anarchist responses to this?

Mexican government propaganda declaring 2022 the year of Ricardo Flores Magón.

Like I said, from the emergence of the modern Mexican nation-state, in 1917 and 1918, processes of recuperation and of rewriting history begin, of beginning to place figures within their imaginary pantheon. So, they start to recuperate figures that the Mexican state itself, or at least that the winning or militarily triumphant faction of the conflict, which was the Constitutionalist faction, had killed, such as Zapata or Pancho Villa. Or Ricardo Flores Magón, although he wasn’t killed directly by the Mexican government, it was the gringo government, but Magón was persecuted his entire life by the Mexican government on both sides of the border.

So, from the very birth of the modern Mexican nation-state, this recuperation of figures began as a means to legitimize itself, to say, “We are the heirs of the revolution.” The Mexican Revolution is a process, a conflict, that is extremely complex. You can’t say that it was A against B, because there was C, D, E, F, G. It was a fight among many factions, at some points factions clashed that were previously allied. In the end, the faction that wins begins to recuperate these figures, to position them as their forebearers, and that is precisely where this version of Ricardo Flores Magón as the precursor of the Mexican Revolution comes from.

It does this without understanding, or without wanting to understand, or without wanting to analyze – because it suits the state, it suits the official history – that Ricardo Flores Magón himself at one moment was strategically allied with the anti-reelectionist faction of Madero but ended up breaking with it and confronting it, including militarily, just as he confronted all the subsequent groups that took power. So, they take away that anarchist, radical part from Ricardo, they decaffeinate him, as we say, and leave him as just a simple journalist, writer, who started the struggle against Porfirio Díaz. According to the official history, Magón begins in 1900 with the founding of Regeneración and in 1910 disappears from the map because it is Madero’s anti-reelectionist party that takes the lead in the struggle against Porfirio Díaz and all that subsequently comes afterward with the war.

But the fact is that the Mexican Liberal Party and Ricardo Flores Magón were active well into the 1910s, until 1918, the year he was imprisoned. But Librado Rivera continued until almost the 1920s, promoting workers’ movements in Villa Sicilia with the CGT, as did Nicolás T. Bernal and others in the PLM who continued the struggle, continued organizing, continued fighting, even after the death of Ricardo Flores Magón and of course well after 1910. The Mexican state has always done this, appropriating figures, appropriating history, turning it into its history, twisting it for its convenience. In the case of Magón, there are streets with his name, schools with his name, a metro station with his name, there is even a police station with his name.

The Mexican state that emerged from the revolution was a state that for seven decades governed through its different parties, first the PNR, the PRM, and then the PRI, but in the end it’s the same, just changing the name. And it governed via a corporatist state project through the creation of clientelist and populist organizations such as the CTM (Confederation of Mexican Workers), the CROM (Regional Confederation of Mexican Workers), the CROC (Revolutionary Confederation of Workers and Peasants), and others, so as to have control over the population and over the workers’, peasants’, and popular organizations.

In the consolidation and creation of this corporatist state, it recuperated revolutionary figures for its pantheon and incorporated them into its discourse, allowing the state to position itself as the heir of the Mexican Revolution, the product of the Mexican Revolution. The PRI, for its entire life, has claimed to be the heir of the Mexican Revolution, to be a revolutionary political institute, the Institutional Revolutionary Party, based on that project, on that discourse of, “We come from Magón. If you trace back, if you look, if you search for our trail, you can follow it to those precursors of the Mexican Revolution, such as Ricardo Flores Magón.” It sought to give itself legitimacy, legitimacy to maintain control, be it through clientelist measures or direct repression, such as jail or, in many cases, assassination.

There is a break when the opposition under Vicente Fox wins the presidency in 2000, but this discourse about heroes of the revolution is still maintained, and figures that were antagonistic to one another are placed in there. And now, the Fourth Transformation (4T), the current government [of MORENA, the National Regeneration Movement] is also obviously seeking this legitimacy, or to legitimize itself as a leftist force. At least this is the discourse that they’ve used since their movement began: that they are the real parliamentary leftist option in this country. And for their own ends they have recuperated figures such as Zapata, who they paid homage to and dedicated an entire year to in 2019, and in 2022, declaring it as the year of Ricardo Flores Magón.

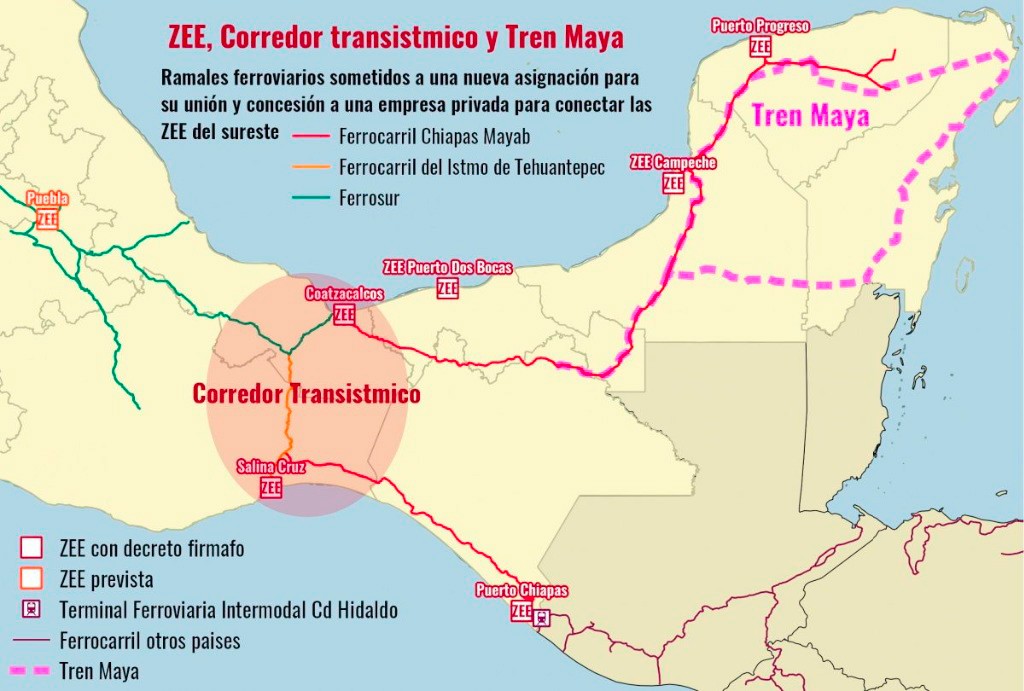

We’re not surprised by this, but it seems to us an attempt to incorporate, to legitimize MORENA as an option, as a leftist force, when it really is not. In fact, the 4T, MORENA, has maintained the foundations of the capitalist system and has intensified policies of territorial dispossession through the promotion of so-called mega development projects. Projects such as the Maya Train or the Trans-Isthmus Corridor, that, at the cost of dispossessing the Indigenous peoples of these regions, the only thing they will do is bring more profit for companies and big capitalists with the placement of industries in the region and the consequent environmental damage.

Map of the Trans-Isthmus Corridor and Maya Train.

But this also works perfectly for the geopolitics of the region, because the United States has put a lot of pressure on Mexico to stop northward migration. What they seek to do by placing these industrial belts precisely in this zone is to contain migration, playing a little bit the role of guardian, of the immigration police for the United States. So, the 4T needed leftist legitimacy that it was losing. It effectively arrived in 2018, with the support of the majority of the population, but a population that was fed up and disenchanted with both 70 years of the PRI and almost 20 years of governments of the other political force, the PAN (National Action Party). They voted for MORENA not because they were leftists but because they weren’t more of the same, they weren’t the PRI and they weren’t the others.

They came into power with great electoral support, but it has been eroding. I don’t want to say that they have lost support, as they continue to have a lot of support, but I think that they also needed to legitimize themselves as a different leftist option. Sectors that historically had supported them have stopped doing so because what they see is that it continues to be more of the same, they continue practicing and implementing the same policies. So, to pay homage to Magón, I don’t think that’s the solution for MORENA, but it was something that they needed, to incorporate a figure like Flores Magón into their discourse, into their imaginary.

Regarding the anarchist responses, the figure and memory of Ricardo Flores Magón and the PLM have always been kept very much alive within anarchism here in Mexico. Regeneración, the newspaper founded by Ricardo Flores Magón, ceased to circulate in 1918, but in the ‘30s and ‘40s, with the founding of the first Anarchist Federation of Mexico, the FAM, the publication of Regeneración was resumed and that lasted until the ‘70s. So, the figure, the thought, the practice, the vision, the activity of Magón has always been very present within the memory and history of anarchism here in Mexico. There were cultural groups, such as the Ricardo Flores Magón Cultural Group headed up by Nicolás T. Bernal, one of the last living Magonistas, which was dedicated to republishing the writings of Ricardo Flores Magón in book form.

In the ‘80s and ‘90s, anarchism lost a little of its presence in social movements here in Mexico, and withdrew towards the counterculture, to punk collectives and that sort of thing. The figure of Magón continued to be very present there. At the end of every November, Magonista Days began to be held, including in 1997, if I remember correctly, there was an initiative from several organizations, among them the Social Reconstruction Library, the CIPO-RFM (Popular Indigenous Council of Oaxaca – Ricardo Flores Magón), the Authentic Labor Front (FAT), the community of Eloxochitlán de Flores Magón, and other organizations convened what was called the People’s Year of Ricardo Flores Magón, which was a year of various activities in different places that culminated with compañerxs from Eloxochitlán visiting the tomb of Ricardo Flores Magón.

The figure, the memory of Magón has always been there. There have always been activities, collectives, organizations that in some way have tried to keep him alive, and not just within anarchism but in other autonomous and autogestive movements, such as Indigenous movements. There is the CIPO, which I already mentioned, and other organizations that claim the figure of Magón and his thought, some because they are also from Oaxaca or because they are Indigenous peoples or because they find some affinity with him.

IGD: Can you share what happened on November 21 at the gravesite of Ricardo Flores Magón?

November 21 is the anniversary of the murder of Ricardo Flores Magón, and every year, or almost every year, anarchist compañerxs meet at the tomb of Ricardo Flores Magón to pay homage to him, to try to keep the memory of Ricardo Flores Magón and anarchism alive.

But also, and as part of these attempts by the state to recuperate the figure of Magón, there is an official event, often by the government itself, or on some occasions by some of these corporatist sell-out unions. On this occasion, some of us thought there was going to be an activity on the part of the state, but no, the government, the Mexican state, the 4T, held an official act of homage to Ricardo Flores Magón in the National Palace, where some academics, researchers, clowns lent themselves to the circus of a government paying homage to an anarchist. But yes, at the tomb there was an act on the part of the CROM, the Regional Confederation of Mexican Workers.

Upon arrival, the contingent of anarchist compañerxs held a counter-protest that denounced the hypocrisy of this organization paying homage to a person who, if he were alive, would surely disapprove of their actions in the first place, but not just that, he would fight against them. The counter-protest pointed this out, the contradiction, the hypocrisy of corrupt union leaders paying homage on that day. And it pointed out that Ricardo Flores Magón had been an indomitable anarchist his entire life, so much so that it cost him his life, and that all his life he had been persecuted by governments, so that on the day of his death, on the anniversary of his death, it was necessary, or at least important, that anarchists come out publicly to say that the memory of Ricardo Flores Magón is anarchist memory, it is memory of the struggle, it is memory of the revolution, it is not the memory of union bureaucrats, much less the memory of power.

This counterprotest was taking place at the same time as the official act, an act where the figure of Magón was exalted as a precursor to the revolution, as an intellectual and a journalist. There was a moment when some compañerxs, in a performative action, approached the stage of the CROM rally to paint a banner and pass in front of them waving a black flag. This provoked the bodyguards, the fighters in the CROM to begin to pushing and pulling and trying to take the flags away from the compañerxs, which led to an initial struggle, an initial confrontation. There was shoving, there was aggression on the part of the CROM, they threw some fists which were answered in turn by some compañerxs with their flags, but it did not go any further.

Their rally continued, or tried to continue, as the anarchist compañerxs began to shout slogans, “Down with the state, death to the state,” which led the leaders of the CROM to decide to suspend their event, and to end it, what they did was sing the national anthem. This provoked the anarchists to shout even louder. The rally ended and there was a threat issued by the secretary general, the leader of this confederation, to one of the compañerxs who was there, where he directly told him, “We’re going to kick your asses.” Immediately after that, the CROM fighters began to provoke, began to push, and began to hit.

There was a ratio of four or five against one. The beating was harsh, and they didn’t stop swinging until those who identified themselves as cemetery security intervened, security that had been there the whole time but that only stepped in once the CROM tired of hitting.

IGD: What is the CROM and why did its members attack anarchists?

We already talked a little about this, the CROM is one of the corporatist workers’ unions that was founded in 1918, at the behest of power, at the behest of the government as part of a project, a strategy to maintain control over the popular forces. The armed conflict had just ended, and the last thing they wanted was more revolts, more conflicts. In 1918, there was a general strike in Mexico City, the leaders of which were jailed and sentenced to death. So, that is a bit of what the tone was like in the government’s dealings with workers’ struggles. But there arrived a moment when they said, “No, instead of having the workers as enemies, I’m going to turn them to the dark side, I’m going to have them here and more aligned and controlled in an organization that I can control, where I can say, ‘Yes’ and ‘No,’” and that is how the CROM was founded.

This doesn’t mean that at that time there were no independent, radical, autonomous workers’ movements. There was the General Confederation of Workers (CGT), the anarcho-syndicalist confederation, that, in fact, the ‘20s were marked by fierce confrontations between the CROM and the CGT, confrontations that even resulted in deaths, because they were armed confrontations. The CGT, little by little, abandoned its anarcho-syndicalist positions and was coopted by the state. It still exists today, but it is now a completely corporatist union.

Since its birth, the CROM has been just that, a state project to control the workers. And since its birth, it has been in conflict with other expressions, with the radical, autonomous expressions of the workers’ movement and social movements. As I already mentioned, the CROM, together with other unions, formed part of this project to legitimize the Mexican state, appropriating from the history of the revolution, appropriating revolutionary figures, and in the case of the CROM, it has always tried to recuperate and appropriate the figure of Ricardo Flores Magón for a particular reason. When Ricardo Flores Magón died in 1922, he died in the United States, and so to bring back his body the railroad workers, part of the CGT, organized themselves, but so did the CROM. The CROM also intervened and helped to have the body of Ricardo Flores Magón transferred from the United States to Mexico. So, it’s been a little bit of that, of living off that and recuperating that.

IGD: What was the result of the confrontation?

In terms of compañerxs injured, because there were injuries, it was an unequal confrontation, it must be said, but I think we prefer to say that it was that: a confrontation. It’s not that we went with the idea of having one, that wasn’t the idea, the idea was to have a counterprotest, to make clear that at 100 years the memory of Ricardo Flores Magón is anarchist memory, and anarchist memory isn’t in the museums, it isn’t dead. It is still alive and still present in the struggles, in the struggles for territorial defense, in the struggles for better living conditions, in the struggle for the preservation of cultures, it is still alive; that is what we wanted to make clear.

At no time were we looking for a confrontation, not with the police nor with anyone else, but rather to raise our voice and say that anarchism is neither dead nor defeated. In that sense, we believe that to take that position is to confront them, to confront power, to confront the state. So, we prefer to say it was a confrontation, we don’t conceive of it as an aggression and we’re not victimizing ourselves. We take the stance that from the moment we position ourselves against the state, against this farcical recuperation of Ricardo Flores Magón, we are confronting them. And obviously, as it has always been, the state reacted and reacted violently. Understanding the state not just as the government, but also as these corrupt unions that historically have been part of controlling the working class.

They reacted as the state has always reacted, violently, aggressively, and the result was that several compañerxs were beaten, some with injuries, two of them much more serious. One of them with a fracture in the left wrist that required surgery and the other with multiple facial contusions, mainly in the region of the eyes, which caused the eyes to swell. Fortunately, the two compañerxs received prompt medical attention and are out of danger.

For the moment, and thanks to the support and solidarity of compañerxs in this region and others, in the United States, in Europe, we have been able to raise a solidarity fund that allowed for us to cover the medical, rehabilitation, and food expenses of the injured compañerxs who are unable to work for the time being.

IGD: What support and solidarity are needed for the injured compañerxs?

A call for solidarity was issued to raise funds to support the expenses of the injured, and fortunately the response was good. So far, the medical and rehabilitation expenses have been covered. We hope that there will be no major complications and that we won’t incur more expenses. However, we continue to call for solidarity. People can send an email for more information on how to offer financial support.

But beyond economic support, which is obviously important, what we’d like is for this to be known and shared, but not just what happened that day in terms of us being attacked. Yes, it’s important, but it is only an illustration of a much broader issue, which is that there is a narrative on the part of the government, the state here in Mexico, that things have changed, that since 2018 and the 4T, Mexico is changing, things are getting better. But what happened at the tomb of Ricardo Flores Magón is an insignificant example that things have not changed, that things continue to be exactly the same, that the forces of capitalism are still alive. The CROM is one such force, but the CROM is one amongst many.

The same 4T is propping up and strengthening capitalism by implementing economic policies of exploitation and dispossession. And there will be those who say, “Hey, but the minimum wage is going up here in Mexico.” But from my point of view, it’s logical, obviously they’ll have to raise it, this is one of the cards they are playing now, that there is a 20 percent increase in the minimum wage, yes, because if they don’t increase it, people will die of hunger. It’s not a policy meant to improve things, it’s simply alleviating misery, it’s taking pressure off, but really what remains is dispossession, exploitation, misery, repression, but now dressed in purple [the color of MORENA] and disguised as leftist. And those forces that have maintained control and benefited from these policies, such as the CROM, are still there, benefitting without a care.

For us, it is very clear and obvious that there has been no change, no transformation in this country. One is needed, but those above won’t do it, the CROM won’t do it, they’re not interested, no matter how many tributes they pay to Magón. We have to do it ourselves, from below, the peoples, the collectives. I believe that beyond economic support, it is that, to invite folks to continue building these networks of support, of solidarity, of exchange, to let it be known that here in Mexico things haven’t changed and that we anarchists are still fighting – beyond a commemorative year like this one in memory of Ricardo Flores Magón – we continue creating projects, libraries, publishing houses, radio stations, social centers, in short, a series of initiatives.

We also continue to have compañerxs persecuted and imprisoned for these struggles, such as the case of our compañero Miguel Peralta, a compañero who was born in the community where Ricardo Flores Magón was born, Eloxochitlán de Flores Magón, a community that has been confronting and living through political conflict for years, where on one side there is the community and its assembly confronting the other side, a cacique group and political parties. As a result of this conflict, there are seven compañeros imprisoned, compañerxs displaced from the community, and compañerxs with arrest warrants, as is the case with Miguel Peralta. He had initially been sentenced to fifty years in prison and, thanks to solidarity and pressure, he was released. Now all the sudden they are saying his sentence has been reinstated. Things like this continue happening in this country, so homages to Ricardo Flores Magón in the National Palace are worthless when nothing has changed. I think that is the importance of the message that we would like to get out.