Filed under: Analysis, Anarchist Movement, Community Organizing, Critique, Featured, US

The first in a series looking critically at mutual aid programs that exploded following the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic and the George Floyd rebellion. Originally posted to Notes on Mutual Aid.

Zine PDF For Printing HERE

In Spring of 2022 we were rejected by our anonymous friends at PugetSoundAnarchists.org. The site admins declined to publish a report-back submitted by a long-running project working with local mutual aid groups. They reasoned that the project in question wasn’t really mutual aid and thus not relevant to anarchism. In true anarchist fashion, the only solution that came to our minds was to write thousands of words telling them why they’re wrong…and why we were also a bit wrong.

This project comes out of our frustrations and hopes working with local mutual aid and anarchist projects for some years. The recent proliferation of groups taking the name “mutual aid” has led to an explosion of new and valuable organizing. But it has also spurred confusion over what exactly mutual aid is, and how its radical potential profoundly differs from charity. This zine is the first in a series that will explore and critique the budding movement of mutual aid groups around the Pacific Northwest. Our own experiences, observations, and research are synthesized with accounts gained from networking with other groups near and far.

Following this zine’s exploration of mutual aid’s history and theory, the next zine will explore the various enemies and allies mutual aid crews may encounter. A collection of helpful tips, tricks, and firsthand knowledge will follow. The final entry will provide more detail on various mutual aid groups as well as thoughts and hopes for future organizing. We hope it will provide both practical information and food for thought.

What Is Mutual Aid?

The past three years have seen an explosion of self-described mutual aid groups. The first wave formed in the early days of the Covid-19 Pandemic as grassroots organizers sought to build community support amid the cascading crisis of shutdowns, layoffs, and lockdowns. Many of these groups looked to Mutual Aid Disaster Relief networks established during recent natural disasters for inspiration. The George Floyd Rebellion sparked the next wave; as action in the streets slowed, many desired to stay active and saw need in every direction.In Seattle and many other towns, local government eased off everyday repression of unhoused folks during the early pandemic but restarted with a vengeance as protests died down. Much of this new wave of mutual aid sought to support these unhoused neighbors.

While some mutual aid projects struggled to build long-term activity, particularly in the first wave, others have carried out excellent work for several years at this point. Some of these groups are still creating new ideas and dynamics or growing in scope. There was a lot of initial energy and innovation, but we have also seen a lot of settling into patterns accompanied by burnout.

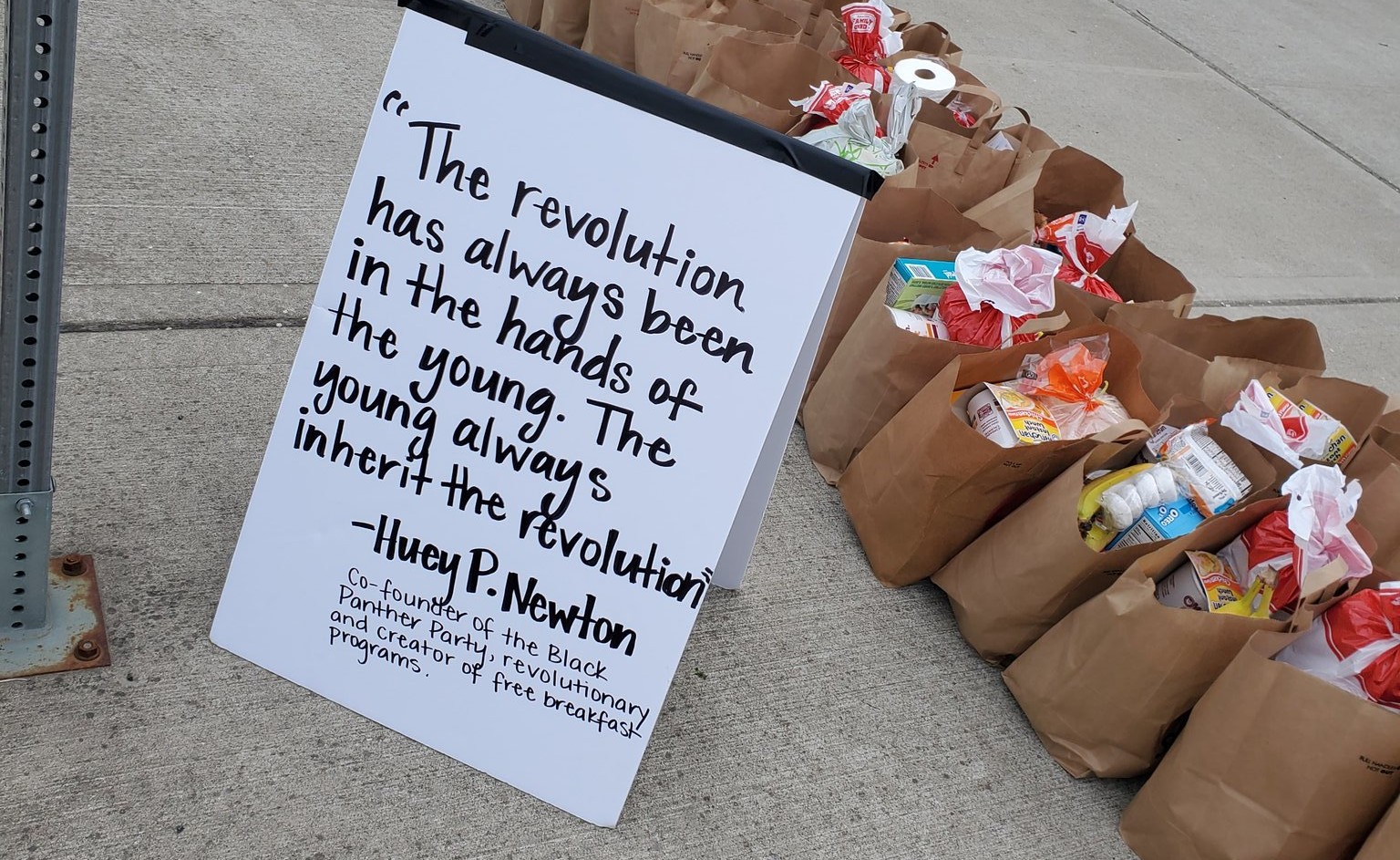

Feeding the kids with Tacoma Mutual Aid Collective at McCarver Elementary until noon or until we run out. pic.twitter.com/sRAkfE5Wcg

— J. (@GritCityMissfit) March 21, 2020

Early in the Pandemic it felt like the term “mutual aid” was on everybody’s tongue. Talking heads were very successful in getting the basic definition out there, but this definition frequently lacked the context for work being done in the streets and was removed from a broader revolutionary analysis. Taking a different approach, there were a ton of ‘how-to’ zines that were super helpful in getting infrastructure up and running but lacked a framework for thinking bigger. Many things have been called mutual aid, from e-spanging to public feeds. We have to consider deeper dynamics at play and take an honest accounting of our capacities.

Distros can meet daily needs in a crisis, but what happens when the crisis is every day? When hard-built relationships are constantly under attack as people are kicked from one curb to the next? Endless crisis response becomes unsustainable.

Where do we go from here? One starting point is rethinking our conception of mutual aid. How do we take this beautiful idea and apply it to our current landscape?

A whole lot of people have given definitions of mutual aid. A helpful working definition is that mutual aid encompasses the exchange of goods or resources with the expectation that the entire community will benefit. A resource can be thought of broadly, moving beyond material goods into things like physical spaces, legal support, or sharing time or knowledge. It’s about more than just giving things away, but rather seeks to reorient social relationships around interdependence – a world where we can freely rely on each other.

We keep these ideas of free association, of community control in our hearts and want to build towards them. But we live in a flawed and broken place that comes with baggage, and we understand why many people feel unable to just directly live their ideals. We have to take the real world into account. We need our hopes and ideals as well as an understanding of the current political structures to move forward. Survival is important but we need more. Using mutual aid as a compass can help us keep on the right track through the constant struggles of everyday work.

Century-old texts and decades-old struggles provide profound inspiration and warnings of pitfalls. Mutual aid has a privileged place in anarchist discourse in-part due to the eponymous 1902 work by Peter Kropotkin. He argued that societies and species survived and prospered because their members cooperated with one another, as opposed to the contemporary social Darwinist obsession with competition.

Mutual aid societies for workers once provided a place to find support in hard times as well as a network for education and sociality. Many such organizations laid the foundation for later labor unions; modern unions with a strong, fighting culture almost invariably practice a culture of everyday mutual support for their members beyond the job site. On a broader level, many powerful movements seeking to liberate an oppressed community develop mutual aid dynamics among participants. Radically breaking from hierarchical control over support and resources is itself an act that builds and sustains resistance to capitalist, colonial, or patriarchal domination.

A new interview with the Tacoma Mutual Aid Collective about why we need solidarity not charity and how we will only survive the pandemic with #MutualAid https://t.co/mdmGtolUGt pic.twitter.com/pWx1qUcb5N

— Shane Burley (@shane_burley1) March 30, 2020

Kropotkin and other old white radicals did not invent mutual aid from thin air, instead frequently drawing on and at times appropriating community dynamics they witnessed in other societies. One practice Kropotkin cited based on his 1897 visit to the region is a set of related traditions by Coast Salish and neighboring peoples’ often known as Potlatch, or in Lushootseed speaking communities as Sgwigwi. Local communities frequently held great events where accumulated wealth was distributed to all; struggling community members got the support they needed while friendly relations were maintained with neighboring towns. In the case of Potlatch, Kropotkin’s status as an outside observer meant that his assumptions suffered de-contextualization. Even as the bulk of community material wealth was distributed, Potlatches were also a means of reinforcing social hierarchies. Those who had the most to give were expected to give the most, but in return gained prestige as leading figures in the community. Lacking this understanding, Kropotkin viewed the Potlatch as a pre-capitalist form of communism, the principle of an egalitarian society in which resources flowed “from each according to their ability, to each according to their need.”

It should also be noted that while Kropotkin and his contemporaries ostensibly drew on local indigenous traditions, mutual aid societies and cooperative colonies founded by white settler radicals frequently fought to take land and resources from these same indigenous groups. While it can be valuable to take inspiration from many sources, it is important to root our conception of mutual aid in our own context rather than romanticizing other cultures or the past.

Today we find ourselves trying to influence our communities in the context of gentrification, continuous war, and environmental catastrophe, but also amid revolt from below across the globe. Anarchism in the US is in a weird place, many of our ideas and practices have gained a certain level of acceptance in the last few years, but some of these ideas have become watered down. Practices are repeated even when divorced from their original context. If we want to build our communities and movements to meet the challenges we are facing we will need to learn from each other, learn from our past, and be critical about our own projects and the projects that we encounter. We should take ourselves seriously and be honest about the direction we are headed.

We hope to provide useful tools. We hope people read this piece critically and use it to start conversations. Contexts are different, not just in terms of physical space but involving different people who have their own experiences. But tools are meant to be used and any bare strategy or tool-kit can be used by anyone. Police departments use “mutual aid” to support one another when they would otherwise be overwhelmed. Many fascist groups do community meals (with a very different idea of community from our own); some even have squats, fight the police and engage in other forms of activism that would more commonly be associated with anarchists. It is very important that we don’t just follow a form, but that we are intentional and building from a deeper analysis.

Doing a little distro and helping people survive is great, but if we are trying to build something bigger, we also have to incorporate it into a broader set of practices. Our communities and our friends are under constant attack and we need to do more than just respond. We must defend the gains that we make from the state, reactionary violence, and liberal co-option, but we have to take a more holistic approach. This can and should look a lot of different ways. We must build strategies not just for defense, but for building power with the people and communities we’ve built trust with.

A Local History of Survival and Struggle

Intra-community liberation movements blossomed in the late 1960s. Most famous were the Black Panthers, whose community-oriented “Survival Programs” were as vital to their legacy as their better-known armed resistance to white supremacy. Seattle’s Panthers created clinics, medical testing, jail visitation, and free breakfast programs for the Black community to be a “survival kit of a sailor stranded on a raft… to sustain himself until he can get out of that situation.” “Survival pending revolution” was both an organizing tool and a concrete expression of Panther politics. Alongside these formal programs, the Panther’s developed a culture of supporting community members in need. Local Panther Captain Aaron Dixon recalled how the local Panther headquarters often served as an informal safe-house and shelter for sex workers and other folks on the streets.

The Panthers and the Black Power movement profoundly influenced movements to liberate other marginalized communities. Indigenous peoples around the region reclaimed fishing waters at sites like Frank’s Landing and Lake Washington, and transformed occupied abandoned government facilities into community centers. Chicano activists took over an abandoned Seattle school that still serves as the centerpiece for a community center and low-income housing. Queer activists established networks of safe-houses and shelters for those forced to live rough while demanding visibility and respect. Many siloed away in asylums and state mental institutions organized to end institutionalization and provide real support as integrated members of the community.

The Neoliberal counterattack of the early 1970s was launched as the initial momentum of these movements slowed and internal conflicts emerged, often around a lack of intersectional awareness towards the needs of the most marginalized within particular communities. The only limited concessions that saw the light of day were those that could be framed through an economic logic of slashing state expenses while simultaneously increasing control over everyday life.

Widespread programs of “urban renewal” were initiated. Trendy apartments and galleries replaced the numerous single-residence-occupancy hotels that had long been a cheap place for anyone to spend the night in Pioneer Square, Belltown, Chinatown, and other neighborhoods. Seattle’s defacto residential segregation laid the basis for new gentrification. Simultaneously, state investments in public or social housing plummeted. Governments saw an opportunity to cut budgets and appease some disability liberation advocates by shuttering mental hospitals, but provided minimal support to the hundreds of thousands no longer committed.

With this came a massive expansion of “nonprofits” and “Non-Governmental Organizations” (NGOs) receiving state support; a never-ending, accountability-obscuring shell-game. Many of the most militant fighters for liberation were locked up or killed. Those willing to compromise with power received cushy grants and connections in return for “managing” but never truly solving the problems plaguing their communities.The husks of many former survival programs lingered, stripped of their connection to liberatory struggles driven further underground. Survival alone was on the agenda, revolution left out in the cold.

Starting in the 1980s, the deadly power of this malicious neglect reared its ugly head as the AIDS and Narcotic epidemics overlapped with the state’s War on Drugs. The Reagan administrations’ willful misinformation and intensified policing bordered on genocide. Grassroots mobilization became necessary simply to survive. What is now called “Harm Reduction” developed as organic practices of survival and care by folks “living, working, and dying on the streets.”

Drug users, radical queers, rogue healthcare workers, and anarchistic activists recognized the particular danger of needle-sharing in spreading HIV. They began exchanging clean needles acquired through a variety of creative means with anyone who needed them. The first needle exchanges in the United States emerged in 1988. Queer activists in Seattle’s ACT-UP chapter and Dave Purchase in Tacoma initially launched underground exchanges, setting up tables with supplies where they knew they could find fellow users. Not long after queer radicals in Bremerton followed suit; the Ostrich Bay Needle Exchange started out of an old gay communist’s garage. Ostrich Bay went mobile when the city declared the garage-exchange a public nuisance, but the same garage still stores harm reduction supplies over three decades later.

Harm Reduction sees drugs as an inescapable fact, not a moral issue. It seeks to reduce the harm associated with use. But the tensions at play since Harm Reduction’s days of illegality are illustrated by asking “whose harm?” Answers that are focused on the individual user, or a marginalized community one is a part of, draw easy parallels between Harm Reduction and older Panther Survival Programs. Many early developers of Harm Reduction practices saw their activities in this very light. Their efforts were oriented towards deeper social roots of harm; folks needed to survive to be able to fight.

Yet other answers were just as (if not more) focused on abstract harm to “the social order.” From this perspective, Harm Reduction could become a new logic of governing and control. The inevitable byproducts of a toxic system must be managed so the system can keep limping along. A lone public health officer may not have shared the anarchist politics of a needle exchange they clandestinely supported, but no one else was working to reduce the deadly epidemics before their eyes. As these efforts gained traction and broader support, however, a power imbalance emerged. Moonlighting-professionals were best placed to receive a new wave of grants and often backdoor state sanction. This spurred a de-politicization of the Harm Reduction movement still underway. Growing nonprofits like Seattle’s Downtown Emergency Services Center (DESC) began to embrace “Harm Reduction” in this context by the 1990s.

The Mutual aid group @TheWitchesPDX , who have been providing water and snacks to BLM protesters in Portland, have arrived in Mulino to drop off supplies to firefighters pic.twitter.com/QWaj9Pct7S

— Sergio Olmos (@MrOlmos) September 11, 2020

Many “living, working, and dying on the streets” were not content to remain on the streets. As countless were displaced and evicted every year, urban governments began harsh crackdowns. “Sweeps” was a racially-charged term before the 1980s; it described lily-white police forces rolling through parks in black and brown neighborhoods to arrest and assault anyone unfortunate enough to be in their way, usually under the guise of fighting drugs, gambling, and sex-work. As more folks of all demographics (though always disproportionately BIPOC and/or Queer folks) ended up on the street, they banded together for their mutual protection. People squatted, set up encampments, and built shacks in greenbelts and under overpasses. By the late ‘80s, major urban police departments began launching “Sweeps” against encampments that typically used the same excuses as older racist sweeps. People’s belongings were destroyed and stolen. Those not arrested had to find somewhere else to start over.

In many cities across the United States, homeless and formerly homeless folks organized the National Union of the Homeless. The movement started in 1984 in Philadelphia. People came together to open their first survival project, a shelter run by homeless folks themselves. In 1989 a “take off the boards” campaign coordinated takeovers of vacant homes in 73 cities. Massive public housing complexes abandoned by neoliberal policy were also occupied. By the early 1990s there were full-fledged Union chapters in twenty cities. Unfortunately, a combination of co-option and addiction took its toll on the organization. Some successful projects received major government grants and turned away from the more radical roots of the organization. Meanwhile, many of the most visible street-level organizers struggled to keep in touch amid the exploding crack epidemic. Seattle never had a full chapter of the Union, but people on the streets led a similar movement locally.

In Summer 1990, Seattle hosted the “Goodwill Games.” Thousands of athletes, tourists, and journalists from 54 countries poured in. The city established a “Goodwill Games Crime Suppression Task Force.” County sheriffs and police from Seattle, Tacoma, Kennewick and Spokane ran nightly raids and “street sweeps” with the usual excuses. An event allegedly fostering global “Goodwill” had none to share with homeless folks, an all-too-familiar pattern for high-profile global events.

A group of current and formerly homeless folks organized together as SHARE (Seattle Housing and Resource Effort) and set up a “Goodwill Gathering” in Myrtle Edwards Park for those displaced by the ongoing sweeps. The connections made there persisted. By November SHARE squatted the mudflats south of the Kingdome to establish Tent City 1, a democratically self-managed camp soon home to 166 people. Negotiations with the city won them a handful of temporary buildings. When these agreements expired, SHARE refused to leave until offered permanent accommodations. The Aloha Inn was established as a result, but not without strings attached: the city required SHARE to have a “fiscal sponsor” to oversee grants and large facilities. The Low Income Housing Institute (LIHI) was established as a separate nonprofit from the grassroots, democratically-run SHARE.

Throughout the 1990s and the 2000s, SHARE continued establishing non-permitted, self-managed encampments. The city’s concessions included grants to cover facilities and eventually city-sanction for some tent cities. SHARE annually hosted camp-out protests outside of City Hall in collaboration with Real Change. The largest in 2008 forced the city to implement its current “72 Hour Rule” for clearing encampments, previously (and often still) carried out with no notice. It also saw the first local use of the slogan “Stop the Sweeps.”

But SHARE’s relationship with LIHI was a double-edged sword that divided the struggle for survival from that for systemic change. State support in the 70s helped drive the wedge between formalized Survival Programs and their revolution-minded initiators. Now an emerging Homeless Nonprofit Industrial Complex offered stable if not lucrative careers in ‘managing’ homelessness without solving it. Eventually even some long-term SHARE members made a career out of their efforts. They increasingly ran the show outside the ostensible democratic frameworks on the ground. LIHI, meanwhile, maneuvered with the city to undermine these democratic camps entirely in favor of their own management structures.

These conflicts have only sharpened over the past decade. Tech capital floods into the region, leaving the rest of us struggling to keep our heads above the water. All the while, the people living, working, and dying on the streets keep fighting for their survival. Campers established a series of squatted, collectively-run encampments called ‘Nicklesvilles’ in the late 2000s into the 2010s. Since a group of activists began showing up regularly at the city’s sweeps in 2016, the demand to Stop the Sweeps has grown particularly poignant. A large occupation at City Hall in 2017 brought this call to wider attention, but messy coalition organizing disrupted momentum. Groups like Socialist Alternative co-opted and transformed the original demand (Stop Sweeps, period) into what later became the failed Amazon Tax. As the political opportunists lost interest, though, hard work continued.

Homeless folks have also played an essential, and all-too-often overlooked role in recent social uprisings. The Seattle Police murder of homeless Nuu-chah-nulth woodcarver John T. Williams sparked significant unrest in 2010. The 2011-12 Occupy movement would have been impossible without homeless people forming the backbone of its occupations. The sustained occupation on Capitol Hill surrounding SPD’s East Precinct during the 2020 George Floyd Uprising would have been similarly impossible without hundreds of homeless comrades. Many of them remained in the neighborhood long after the CHAZ/CHOP was officially cleared.

The Present Wave

The groundwork for the current proliferation of autonomous mutual aid projects was laid in the years before the 2020 pandemic and protests. Stop the Sweeps helped facilitate a growing network of folks providing everyday support, while testing out ways to support residents facing imminent sweeps. Autonomous outreach and distro collectives were formed in Tacoma and a handful of Seattle neighborhoods like SODO. Community members in Ravenna and the Rainier Valley began holding weekly popup kitchens, joining long-running projects like Seattle Food Not Bombs. Small networks emerged to collect and distribute seasonal supplies like cold weather and smoke-protective gear. Those organizing around smoke-season in particular looked to the long-running efforts of Mutual Aid Disaster Relief providing community support amid crisis. These efforts provided not just a blueprint but also formative experience for many that started mutual aid groups since 2020.

The messy stew of the early Covid-19 Pandemic disrupted and transformed preexisting social and political networks. Millions were out of work, millions more got a pat on the back and an “essential worker” sticker as compensation for awful working conditions. Almost paradoxically, some poor folks temporarily had more disposable income than they’d ever had. Everyone was impacted by lockdowns and closures. With the world seemingly falling apart, survival was high on everyone’s mind. “Mutual aid” became an explosive buzzword on all sorts

of new tongues.

In Seattle an eclectic coalition established a local “Covid-19 Mutual Aid Network,” a formation paralleled in many other cities and towns. Participants in Seattle’s network sought to unify a diverse set of tactics under one roof. One part of the network wanted to be a clearinghouse for rank-and-file labor agitation during the early pandemic, another sought avenues to pressure the system with demands, while a third and highly visible chunk sought to provide direct aid to people impacted by layoffs and lockdowns.

Seattle’s Covid-19 Mutual Aid Network dealt with growing pains that any new project bringing together a massive range of groups and tendencies is bound to face. Significant media attention and the trendy buzz around “mutual aid” funneled hundreds of thousands of dollars in donations to direct aid programs before a clear framework for how to handle so much money was established. Proposals for utilizing the sizable new volunteer list to try and form locally-based groups for longer-term support never really got off the ground. The organization’s direct-aid wing instead acted as a complex middle-man, matching random volunteers who could pick up some groceries with people who needed them delivered during the lockdown; something like a slower, free Instacart. This wasn’t an inherently bad thing, but lay far from the reciprocity and formation of new social ties central to mutual aid as opposed to charity.

The Covid-19 Mutual Aid Network ostensibly sought to organize on decentralized, non-hierarchical lines. Unfortunately, some participants had little background organizing this way and even less interest in learning how. A messy mix of long-time anarchists, state socialists, and non-profit operatives wrangled over structure. Structural ideas were imported from non-profit environments with little critical reflection how these might function in a loose, rapidly growing group.

When George Floyd’s murder set the world on fire in May 2020, many of the conflicts and limitations within Seattle’s Covid-19 Mutual Aid Network were coming to a head. These were left unresolved as many involved in mutual aid organizing across the continent quickly became active in the uprising. As an organization Seattle’s Covid-19 network more or less went dormant; its large social media pages mostly just repost and highlight projects that emerged afterwards.

Hello everyone here is an unboxing video mutual aid resource COVID-19.

Atlanta survival program:

Is based on projections, we expect that the new coronavirus will have a severe impact on people in Atlanta 🥕 🍎 🍉 🥦 💕 https://t.co/QpSSDONtDG https://t.co/0EKfI5faKW #Covid_19 pic.twitter.com/zQpTy7J0PP— Shanice Turner (@ShaniceSpeaks) May 7, 2020

But the street battles and occupied zones of Seattle’s Capitol Hill provided space for new ideas of mutual aid to flourish. Mutual aid stations sharing all sorts of skills and necessities were established amid a broad ethos of reciprocity. Genuine connections and comradeship were built between those who spent time in the occupied area, whether or not they had a home to return to. Many who traveled from afar to share food and resources around Cal Anderson Park and the East Precinct brought these ideas back to their communities. As one of many examples, visitors from Aberdeen on the Olympic Peninsula returned from the CHOP/CHAZ inspired to bring Mutual Aid ideas to their rural town; among other things they are now the only source of Harm Reduction supplies for their entire county.

As one might expect given the tragic, bloody end of Seattle’s occupied zone, mutual aid organizing was not all sunshine and roses. Messy power dynamics emerged around stockpiles of donated resources as some individuals took up the role of gate keepers. The “No Cop Co-Op” was one visible example; the woman who first set it up quickly clashed with many of the volunteers over her desire to monopolize the collection and distribution of donations. Other participants elected to break up the Co-Op and scatter its supplies when she began doxxing black activists and tried giving orders to barricade volunteers to act as her own security.

As protests continued for months, and the state remained legitimately afraid, many things seemed possible. The city of Seattle disbanded its police Navigation Team in August 2020, previously responsible for overseeing sweeps of homeless folks. Covid emergency conditions had already imposed a moratorium on most sweeps, and many people were temporarily offered hotel rooms. For those on the street this new pandemic was not particularly earth-shattering; pandemics from HIV to Hepatitis have afflicted the poorest and most vulnerable for years without a second-glance. The temporary reprieve from repression thus appeared as something of an opportunity for many.

During this brief lull, the first groups in the present wave of mutual aid were initiated to proactively support homeless neighbors that were establishing communities with a modicum of stability for the first time in years. Perhaps influenced by previous calls for decentralized organizing, Seattle-based crews set up as local neighborhood-based mutual aid collectives. Today these number several dozen, though a few have come and gone. New formations emerged in cities like Everett, Bremerton, and Bellingham while existing projects in Olympia and Tacoma were joined by new groups and faces.

While the Covid pandemic continues to rage years later, the imposed return to ‘normalcy’ included newly intensified attacks on those living on the streets. Vigilante attacks never ceased, and the feeling on the street was that they may have been increasing. But pressure from the state in Seattle re-escalated at the end of 2020 when the City announced plans to kick sweeps back into high gear. A perversely named “Hope Team” was established to oversee this dirty work at the same time as Covid relief programs were being gutted. A new Stop the Sweeps emerged in response out of the growing new networks of mutual aid crews and uprising veterans. Some sweeps have been significantly delayed and everyday support is provided when it otherwise would be absent. Interventions are most effective when local neighborhood groups with established relationships work in conjunction with a broader Stop the Sweeps network. But truly stopping the sweeps will require even more capacity and combativeness. Those in power are determined, and increasing millions have been pumped into terrorizing folks on the streets with often twice-daily sweeps.

The present wave of mutual aid work is at a crossroads. A solid foundation for future work has been established, but it is vital that groups avoid stagnant patterns, non-profit and electoral co-option, or settling into a wholly reactive pattern of responding only when attacks intensify. The dozens of disparate crews around the region must continue building networks between one another to share experiences and resources. The work of helping our neighbors survive while building community able to confront settler capitalism continues.

Further Reading

Articles available at theanarchistlibrary.org

Christopher B.R. Smith, “Harm Reduction as Anarchist Practice: A user’s guide to capitalism and addiction in North America”

Curious George Brigade, “Insurrectionary Mutual Aid”

Regan de Loggans, “Let’s Talk… Mutual Aid”

Zoë Dodd & Alexander McClelland, ”Taking Risks is A Path to Survival” + “Thoughts on an Anarchist Response to Hepatitis C & HIV”

Zines

“The National Union of the Homeless: A Brief History”

“Queens, Hookers, and Hustlers: Organizing for Survival and Revolt

Amongst Gender-Variant Sex Workers, 1950-1970”

“Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries: Survival, Revolt, and Queer Antagonist Struggle”

Books

David Hillard, The Black Panther Party: Service to the People Programs

Nancy E. Stoller, Lessons from the Damned: Queers, Whores and Junkies Respond to AIDS

Local Anarchist Media

Pugetsoundanarchists.,org | Itsgoingdown.org | Sabotmedia.noblogs.org

Some Local Mutual Aid Crews

Aberdeen – Chehalis River Mutual Aid Network

Bellingham – BOP Mutual Aid

Bremerton – Kitsap Food Not Bombs | Bremerton Bike Kitchen

Everett – South Everett Mutual Aid

Port Angeles – Port Angeles Food not Bombs

Olympia – Olympia Food not Bombs

Seattle – A Single Spark | A Will and a Way | Black Star Farmers |

Broadway Aid | Casa del Xolo | Cold World Mutual Aid | Egg Rolls

Community | Give a Damn | Long Haul Kitchen | North Beacon Hill

Mutual Aid | North Seattle Neighbors | Seattle Food not Bombs | Stop

the Sweeps Seattle | Subvert UD | West Seattle Mutual Aid Party

Tacoma – Tacoma Mutual Aid Collective | The People’s Assembly

photo: @GritCityMissfit