Filed under: Analysis, Anarchist Movement, Anti-fascist, Political Prisoners, Repression, The State, US

The following analysis looks at the laws around firearms possession, and what you need to know about potential legal threats in a variety of situations.

In the past several months, at least two radicals have been arrested by the FBI and charged with violations of 18 U.S.C. 922(g), the federal statute which prohibits certain categories of people from possessing, transporting, or receiving firearms. It is sometimes referred to as the “felon in possession” law or “possession by a prohibited person” law. Neither case has gotten much attention in radical circles.

The first was Rakem Balogun, who was arrested in a pre-dawn raid in December 2017 as part of the FBI’s crackdown and repression of so-called “Black Identity Extremists” (FBI-speak for Black people organizing against white supremacy and for self-determination). He is charged with violating 922(g)(9) for allegedly having a prior conviction for a misdemeanor crime of domestic violence. He has pled not guilty and his attorney has filed a motion and extensive briefing challenging whether Rakem’s prior conviction qualifies as a “misdemeanor crime of domestic violence.” Nonetheless, despite the FBI taking months to slowly investigate the case, and then a full week to serve the warrant once it was obtained, prosecutors argued that Rakem was an imminent danger because of his politics and he was denied pretrial release while his case is pending.

On March 9, 2018, a person known as Dallas with Red Guards Austin was arrested by the FBI and charged with violating 922(g)(1) for allegedly having a prior felony conviction. The investigation and arrest of Dallas stems from an incident a month prior in which he was arrested on state charges of Aggravated Assault with a Deadly Weapon for some type of incident in which a gun was allegedly pulled, leading to a search of a residence that Dallas is alleged to have lived at.

One of the points of unity in the old Anti-Racist Action network was the non-sectarian defense of other anti-fascists. This is sometimes difficult, especially in the case of, say, authoritarian communists who have actively denounced, subverted, or maybe even attacked other revolutionary anti-fascists in the recent past, or people with histories of partner abuse. But regardless of how we personally feel about the ideology, praxis, and behavior of groups like Red Guards or Guerilla Mainframe, they serve as canaries in the coal mine for all types of radical movements that may consider pursuing tactics of armed self-defense against fascists, vigilantes, abusers, or others. What happens to them is a warning for what could happen to all of us. The cost of not paying attention and providing support when the State targets more marginal and less popular groups could be enormous in the long run. There is a legitimate debate to be had about what that support should look like and what limits there are, but it should start from the baseline that state repression is never legitimate and that those being targeted deserve support.

The Feds love 922(g) cases because they are relatively easy to investigate and prove at trial, often very hard to challenge for the defense, and carry stiff penalties—up to 10 years in prison. A 922(g) case avoids many of the political credibility issues that come up in elaborate (and often tenuous) conspiracy and entrapment cases. It also builds the FBI’s legitimacy in the eyes of many on the left who are calling for increasing gun control and stricter enforcement of gun laws. But 922(g) is not a statute that radicals have faced very often in recent years—one notable exception being Water Protector Red Fawn Fallis’ case.

These cases illustrate some of the minefield of legal and political issues around firearm possession. A better understanding of 922(g) will help radicals of all stripes make more informed decisions about the choices that are best for them regarding possessing and training with firearms. It also helps illustrate how U.S. gun laws—even the uncontroversial, “common sense” ones—can serve to reinforce other regimes of oppression. For example, some gun laws work in conjunction with drug laws and the War on Drugs to disproportionately criminalize poor communities and communities of color, stripping them of supposed constitutional rights that more privileged communities take for granted. Convictions for drug offenses lead quickly to a complete loss of Second Amendment rights, often for life. Similarly, a young queer or trans person who gets institutionalized by homophobic parents may have also lost their right to armed self-defense for the rest of their life. Conversely, there is a broad exemption from 922(g) for active military and law enforcement.

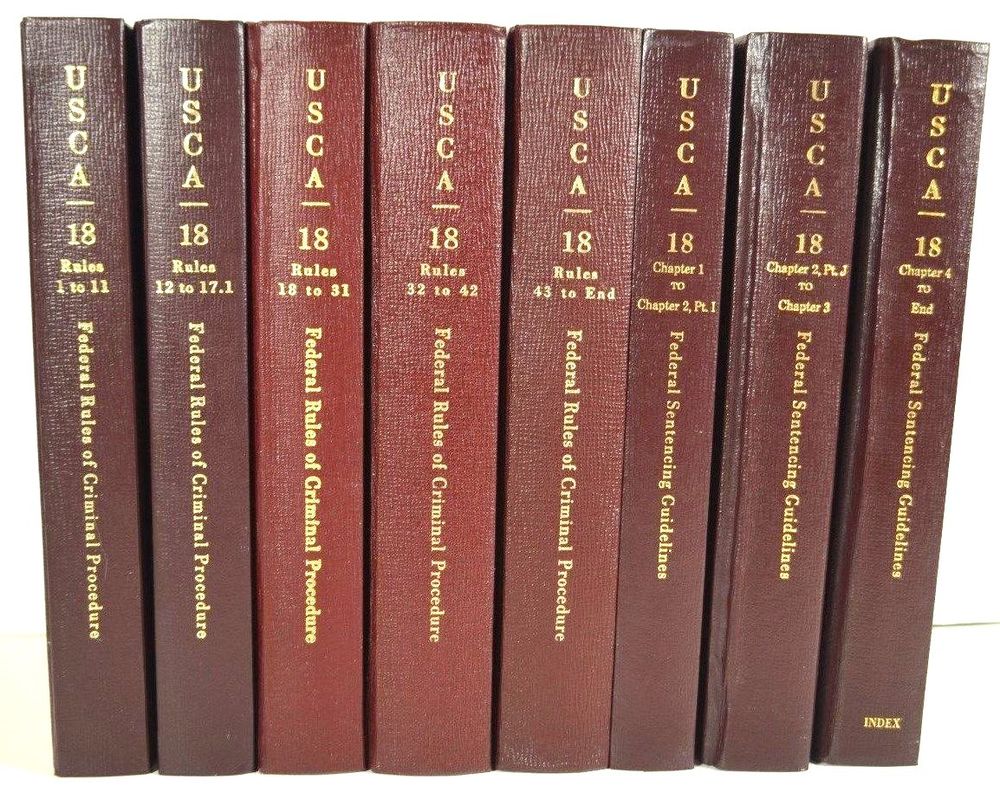

In our first installment, “Know Your (Gun) Rights: A Primer for Radicals,” we provided a broad overview of some of the main legal issues around firearms, including laws regarding who can possess firearms, what is and isn’t legal to purchase, the right to carry firearms, and a cursory look at self-defense laws. Here, we dive a bit more deeply into section 922(g), the primary federal law prohibiting certain persons from possessing firearms.

BUT CAUTION: As always this essay is NOT legal advice, or even a fully comprehensive guide to 922(g) and related federal laws. It is intended for general informational purposes only. Variations in decisions by federal appeals courts could mean that identical factual circumstances may have different legal ramifications in different parts of the country. Additionally, almost every state has a law that is similar to 922(g), but might have important and potentially catastrophic differences. If you have specific questions about how the law applies to your particular situation, you should consult with a competent attorney.

Also a quick warning that lawmakers really like to use language that is oppressive or hurtful in various ways, such as stigmatizing or pathologizing mental health conditions or demonizing and criminalizing migrants. Some of that is necessarily included below.

Introduction to 18 U.S.C. 922(g)

Section 922(g) was first enacted in October 1968 as part of the Gun Control Act (although the prohibition on convicted felons possessing firearms dates back much earlier). Lawmakers first proposed the law in 1963 after the assassination of President Kennedy, but it wasn’t until 1968—the height of the Black Power movement, the anti-war movement, and after four summers of Black rebellion and insurgency in America’s cities—that proponents mustered enough support in congress to pass it.

As of 2016, 922(g) cases account for 8% of federal prosecutions—though in some districts in the South and Midwest, 922(g) cases comprise well over a quarter of the federal caseload. According to the U.S. Sentencing Commission, more than half of all people sentenced for 922(g) cases are Black, and only 24% are white. The average sentence for those convicted of only 922(g) (without enhancements) is 5 years—over 25% higher than it was in 2012.

As of 2016, 922(g) cases account for 8% of federal prosecutions—though in some districts in the South and Midwest, 922(g) cases comprise well over a quarter of the federal caseload. According to the U.S. Sentencing Commission, more than half of all people sentenced for 922(g) cases are Black, and only 24% are white. The average sentence for those convicted of only 922(g) (without enhancements) is 5 years—over 25% higher than it was in 2012.

Section 18 U.S.C. 922(g) says:

It shall be unlawful for any person—

(1) who has been convicted in any court of, a crime punishable by imprisonment for a term exceeding one year;

(2) who is a fugitive from justice;

(3) who is an unlawful user of or addicted to any controlled substance (as defined in section 102 of the Controlled Substances Act (21 U.S.C. 802));

(4) who has been adjudicated as a mental defective or who has been committed to a mental institution;

(5) who, being an alien—

(A) is illegally or unlawfully in the United States; or

(B) except as provided in subsection (y)(2), has been admitted to the United States under a nonimmigrant visa (as that term is defined in section 101(a)(26) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (8 U.S.C. 1101(a)(26)));

(6) who has been discharged from the Armed Forces under dishonorable conditions;

(7) who, having been a citizen of the United States, has renounced his citizenship;

(8) who is subject to a court order that—

(A) was issued after a hearing of which such person received actual notice, and at which such person had an opportunity to participate;

(B) restrains such person from harassing, stalking, or threatening an intimate partner of such person or child of such intimate partner or person, or engaging in other conduct that would place an intimate partner in reasonable fear of bodily injury to the partner or child; and

(C)

(i) includes a finding that such person represents a credible threat to the physical safety of such intimate partner or child; or

(ii) by its terms explicitly prohibits the use, attempted use, or threatened use of physical force against such intimate partner or child that would reasonably be expected to cause bodily injury; or

(9) who has been convicted in any court of a misdemeanor crime of domestic violence,

to ship or transport in interstate or foreign commerce, or possess in or affecting commerce, any firearm or ammunition; or to receive any firearm or ammunition which has been shipped or transported in interstate or foreign commerce.

There are basically two fundamental questions at play: First, is there a reasonable argument that you are in possession or constructive possession of any firearm or ammunition? If so, are you part of one of the designated categories of people prohibited from possessing firearms or ammunition? The rest of this essay will examine both of these questions.

Is there a reasonable argument that you are or were in possession or constructive possession of any firearm or ammunition?

We all know what possession is. If there is evidence that you were actually holding the gun—evidence like photos or surveillance footage, your fingerprints or maybe even DNA on or inside the gun, testimony from someone who saw you with the gun, etc.—prosecutors would have a strong case for actual possession.

The more complicated cases arise around what’s called constructive possession—situations where you don’t have actual possession, but the law treats you like you do. To prove constructive possession, the prosecutor must show that there was connection between you and the firearm which supports the inference that you exercised dominion and control over the firearm. An example would be if your friend buried a pistol in the desert and then gave you a map to where it was buried, just in case you needed the pistol for something. You never touched the gun, but you know where it is, have the ability to access it freely, and can at any time go dig it up or send someone else to dig it up.

Some of the factors that courts might consider in a constructive possession determination include:

- Proximity to the firearm—being very near to a firearm (e.g. same car, same bedroom) isn’t the end of the analysis but looks really bad.

- Knowledge about the firearm—not knowing is a defense, but how do you prove a negative?! The prosecutor will likely use the other factors to try to establish an inference that you did have knowledge.

- Accessibility—was the firearm sitting on the table, in an unlocked drawer, hidden in a closet, or locked in a safe or a different room? Were you able to access it without someone else’s permission?

- Ownership or control over the place the firearm was found—do you own the house, rent it, or stay overnight? If you are just visiting the house, how often do you visit and for how long? Do you have a key to the house? Are you allowed to be there when no one else is home? Do you get mail there? Is it your car? A car you borrowed? Are you driving or just a passenger?

- Any other factors that create a connection between you and the firearm or ammunition.

Possession and constructive possession do not have to be exclusive—multiple people can constructively possess a firearm at the same time. A pistol in a living room closet in a house shared by 5 people might be constructively possessed by all 5 people. Similarly, if you direct the activities of a subordinate who is carrying a firearm (e.g. ordering someone to when to draw their pistol or put it away) a prosecutor could argue that you had sufficient control over that firearm to constitute constructive possession.

Are you part of one of the designated categories of people prohibited from possessing firearms or ammunition?

These categories appear deceptively simple, but that’s where people get caught. Remembering exactly what happened in that case you had 15 years ago isn’t always easy, especially if your attorney never explained it well in the first place and just told you to sign on the line to stay out of jail. Let’s break it down

1. People convicted of a crime punishable by imprisonment for a term exceeding one year

This encompasses almost every type of felony conviction—state or federal, recent or many decades ago, serious felonies or the ones that are just barely felonies. It doesn’t matter whether you were actually sentenced to imprisonment for more than a year, less than a year or not at all—if the law allows a sentence of more than a year, it probably falls under this section.

Two big exceptions though! First, a state-level offense that is classified as a misdemeanor in that state and which has an allowable punishment up to two years does not count as a disqualifying offense for this section. See 18 U.S.C. 921(a)(20). But be careful that you don’t get tripped up by a misdemeanor that carried a possible sentence of 2 ½ years or a misdemeanor that was enhanced to a felony.

The second exception—which just reeks of class privilege and the preferential treatment that the ruling class is extended in the criminal legal system—is for any Federal or State offenses pertaining to antitrust violations, unfair trade practices, restraints of trade, or other similar offenses relating to the regulation of business practices. See 18 U.S.C. 921(a)(20). So, sell a gram of weed? Lose your Second Amendment Rights! Violate antitrust laws? It’s all good Boss!

Whether or not something constitutes a conviction depends on the laws of the jurisdiction where the case happened. So certain deferrals that are successfully completed might not count as a conviction. Also, convictions which have been expunged, set aside, or for which a person has been pardoned or had their civil rights restored is generally not included, with some exceptions. See 18 U.S.C. 921(a)(20). Also, many jurisdictions do not consider juvenile adjudications to be convictions, but some might

However, there is no distinction between a felony conviction from a jury trial and a felony conviction from a plea you took just to get out of jail. Additionally, many people are now seeing states reduce punishments or even completely legalize conduct for which they have old felony convictions (i.e. possessing/selling weed). Unfortunately, the subsequent legalization or reduction in punishment for conduct that resulted in your felony conviction doesn’t get you off the hook, unless you actually get pardoned or otherwise have your conviction reversed.

Also, while 922(g)(1) only covers convictions, 922(n) makes it a crime for anyone under indictment for a felony to ship, transport or receive a firearm or ammunition, but not to merely possess. State laws or your bond conditions, however, might prohibit possession while a felony case is pending

Bottom line: if you’ve ever dealt with felony charges, it would be prudent to at least run a background check on yourself, obtain the records of your conviction from the court, and verify the outcome of your case and the charge, classification, and possible punishment at the time of case occurred.

2. Fugitives from justice

Section 18 U.S.C. 921(a)(15) defines “fugitive from justice” as any person who has fled from any State to avoid prosecution for a crime or to avoid giving testimony in any criminal proceeding. It also includes anyone “who knows that misdemeanor or felony charges are pending against [them] and who leaves the state of prosecution.” See 27 CFR 478.11. This is obviously much narrower than simply having a failure to appear warrant for a traffic ticket in the city you live in, but be careful if you’ve got outstanding cases in another state!

3. People who unlawfully use or are addicted to any controlled substance

This includes any substance on any schedule of the Controlled Substances Act (CSA), but does not include alcohol. See 21 U.S.C. 802(6). Probably the biggest trap is people who use marijuana in states where it has been legalized. Marijuana remains on Schedule I of federal CSA and is therefore almost always “unlawful” to possess or use anywhere in the United States, regardless of state law. Similarly, using many prescription drugs without a valid prescription is also “unlawful.”

This begs the question of what constitutes being a “user” or “addicted.” The Bureau of Alcohol Tobacco and Firearms (BATF) regulations say it includes:

“A person who uses a controlled substance and has lost the power of self-control with reference to the use of controlled substance; and any person who is a current user of a controlled substance in a manner other than as prescribed by a licensed physician. Such use is not limited to the use of drugs on a particular day, or within a matter of days or weeks before, but rather that the unlawful use has occurred recently enough to indicate that the individual is actively engaged in such conduct. A person may be an unlawful current user of a controlled substance even though the substance is not being used at the precise time the person seeks to acquire a firearm or receives or possesses a firearm. An inference of current use may be drawn from evidence of a recent use or possession of a controlled substance or a pattern of use or possession that reasonably covers the present time, e.g., a conviction for use or possession of a controlled substance within the past year; multiple arrests for such offenses within the past 5 years if the most recent arrest occurred within the past year; or persons found through a drug test to use a controlled substance unlawfully, provided that the test was administered within the past year.” See 27 CFR 478.11.

That’s really broad. Any evidence of recent use could be very damning, such as the presence of drugs, residue, or paraphernalia; testimony from an informant or cooperating co–defendant about your drug use; or internet search history or text message history showing evidence of drug-related transactions. Having a state-issued medical marijuana card could also be presumptive proof of unlawful marijuana use. A clever prosecutor could even use someone’s involvement in a recovery program like Narcotics Anonymous as evidence of their addiction rather than evidence of non-use.

That’s really broad. Any evidence of recent use could be very damning, such as the presence of drugs, residue, or paraphernalia; testimony from an informant or cooperating co–defendant about your drug use; or internet search history or text message history showing evidence of drug-related transactions. Having a state-issued medical marijuana card could also be presumptive proof of unlawful marijuana use. A clever prosecutor could even use someone’s involvement in a recovery program like Narcotics Anonymous as evidence of their addiction rather than evidence of non-use.

The situation gets even worse if you were selling or distributing a controlled substance while in possession of a firearm. See 18 U.S.C. 924(c) (prescribing a mandatory minimum sentence of five years or more). Suffice it to say, the War on Drugs and gun control really go hand in hand.

4. People who have been adjudicated as a mental defective or who have been committed to a mental institution

Adjudicated as a mental defective means “a determination by a court, board, commission, or other lawful authority that a person, as a result of marked subnormal intelligence, or mental illness, incompetency, condition, or disease is a danger to himself or to others; or lacks the mental capacity to contract or manage his own affairs.” It also includes a finding of insanity by a court in a criminal case and people found incompetent to stand trial or found not guilty by reason of lack of mental responsibility. See 27 CFR 478.11.

Being committed to a mental institution means “a formal commitment to a mental institution by a court, board, commission, or other lawful authority.” It includes a commitment to a mental institution involuntarily and commitments for mental defectiveness, mental illness, and other reasons, such as for drug use. However, the term does not include a person in a mental institution for observation or a voluntary admission to a mental institution. The term “lawful authority” means an entity having legal authority to make adjudications or commitments. The term “mental institution” includes mental health facilities, mental hospitals, sanitariums, psychiatric facilities, and other facilities that provide diagnoses by licensed professionals of mental retardation or mental illness, including a psychiatric ward in a general hospital. See 27 CFR 478.11.

The law does not distinguish between commitments that occurred recently or many years ago, or those that occurred when someone was a juvenile and those that occurred as an adult (a troubling fact considering what homophobic parents often do to kids who come out or are perceived as queer, trans, or otherwise not conforming with hetero-patriarchal gender norms). In light of recent national debates about mental health and gun violence, it is easy to imagine that this could be a section that starts to get used more often.

5. People who are in the United States illegally or unlawfully or were admitted under a nonimmigrant visa

Being in the United States illegally means that you are not a U.S. citizen and are not in valid immigrant, nonimmigrant, or parole status. See 27 CFR 478.11. This includes people (1) who unlawfully entered the U.S. without inspection and authorization; (2) whose authorized period of stay has expired or who has violated the terms of the nonimmigrant category in which they were admitted; (3) whose authorized period of immigration parole has expired or whose parole status has been terminated; and (4) who are under an order of deportation, exclusion, or removal, or under an order to depart the United States voluntarily.

A nonimmigrant alien is an alien in the United States in a nonimmigrant classification. The definition includes, in part, persons traveling temporarily in the United States for business or pleasure, persons studying in the United States who maintain a residence abroad, and certain foreign workers. The definition does NOT include permanent resident aliens.

A nonimmigrant visa is one allowing temporary entry to the U.S. for a specific purpose, such as for foreign government officials, visitors for business and for pleasure, students, international representatives, temporary workers and trainees, representatives of foreign information media, exchange visitors, fiancées of U.S. citizens, religious workers, and some others. Recipients of nonimmigrant visas typically maintain their permanent residence abroad. The definition of nonimmigrant visa does NOT include permanent residents, so-called “green card holders.”

6. People who have been dishonorably discharged from the Armed Forces

This includes only separation from the U.S. Armed Forces resulting from a dishonorable discharge or dismissal adjudged by a general court-martial. The term does not include any separation from the Armed Forces resulting from any other discharge, e.g., a bad conduct discharge. See 27 CFR 478.11.

7. People who have renounced their United States citizenship

For better or worse, it’s actually not that simple to renounce your citizenship! It generally requires making a formal declaration to a diplomatic or consular official, and paying over $2,000! But renunciation can also occur by certain acts like obtaining citizenship in or pledging allegiance to a foreign state or committing acts of treason or attempting/conspiring to overthrow the government of the United States. It’s not very common, and if you’re curious, the statute is 8 U.S.C. 1481.

8. People subject to domestic violence protection orders

To qualify under this section the protection order or restraining order must meet several requirements. First it must restrain the subject from harassing, stalking, or threatening an intimate partner or their child or the subject’s child, or engaging in other conduct that would place them in reasonable fear of bodily injury. Second it must include a finding that the subject is a credible threat to the partner’s physical safety or explicitly prohibits the use, attempted use, or threatened use of physical force. Additionally, the subject of the restraining order must have been given actual notice and provided an opportunity to participate in the proceedings leading to the issuance of the protection order.

The term “intimate partner” means the spouse of the person, a former spouse of the person, an individual who is a parent of a child of the person, and an individual who cohabitates or has cohabited with the person. It doesn’t include a romantic partner who has never cohabitated with the person.

There are a lot of detailed court decisions about which protection orders do and don’t fall under this category. Suffice it to say that if you are currently subject to a restraining order or protection order against a current or former intimate partner or their child or your child, you should check in with a lawyer before possessing any firearms. And really, instead of worrying about your gun rights, you should be much more concerned with getting the counseling and other help and support you need to change your behavior so that your partners don’t feel like they need restraining orders against you!

9. People who have been convicted of a misdemeanor crime of domestic violence

The misdemeanor crime of domestic violence section is a relatively recent addition to 922(g) and has been the subject of a lot of litigation over the past decade. A misdemeanor crime of domestic violence is any misdemeanor offense which fulfills two requirements. First, the statute defining the crime must include the use or attempted use of physical force, or the threatened use of a deadly weapon. See 18 U.S.C. 921(a)(33). The Supreme Court has said that amount of force necessary to meet the “use of force” requirement is minimal, and can include a slap or light shove. Even the reckless—rather than intentional—use of force counts as well. This includes most assault and battery statutes.

Second, the offense must have been committed by a current or former spouse, parent, or guardian of the victim, by a person who shares a child with the victim, by a person who is or has cohabited with the victim as a spouse, parent, or guardian, or by a person similarly situated to a spouse, parent, or guardian of the victim. It’s not clear exactly what “similarly situated” means, but certainly a romantic partner that you have cohabited with would qualify.

Many people mistakenly believe that if their prior state-level conviction did not get labeled as “domestic violence” under the laws of that state then they are safe. This is absolutely not true. Only an analysis of the actual statute that you were convicted of, as well as consideration of who the victim of the offense was, can determine whether or not your conviction qualifies as a misdemeanor crime of domestic violence.

Like with felony cases, the question of whether a case resulted in a conviction is based on the laws where the case occurred. There is no time limit on which convictions qualify. However, there are statutory exceptions for cases in which the prior conviction was obtained in violation of certain constitutional rights, such as the right to counsel or the right to a jury trial. There is also an exception for convictions which have been expunged, set aside, or pardoned.

Bottomline, if you have any criminal history that involves any physical contact or any threats between you and a partner or your child, you should be taking a close look and perhaps seeking legal help to determine whether it falls under 922(g)(9).

What about that interstate commerce part in the statute?

You might have noticed that the statute only prohibits firearm/ammunition possession “in or affecting [interstate] commerce.” Common sense would suggest that if you bought your firearm in the state you live in, from a company in that state, and you’ve never left the state with it, you might have a defense to prosecution! Unfortunately, federal courts have said that the connection to interstate commerce need only be minimal, so any firearm/ammunition that has ever crossed state lines falls under the purview of 922(g). With rare exception, this includes most firearms and ammunition.

Cops are special

We mentioned near the top that there is a broad exception to 922(g)—and many other federal firearms laws as well—for active law enforcement and military. Section 18 U.S.C. 925(a)(1) says in relevant part:

The provisions of this chapter, except for sections 922(d)(9) and 922(g)(9) … shall not apply with respect to the transportation, shipment, receipt, possession, or importation of any firearm or ammunition imported for, sold or shipped to, or issued for the use of, the United States or any department or agency thereof or any State or any department, agency, or political subdivision thereof.

The U.S. Attorney’s Manual (quoting an advisory letter from the BATF), in the section related to prosecutions under 922(g)(8) for people possessing firearms while subject to a domestic violence restraining order, states:

The U.S. Attorney’s Manual (quoting an advisory letter from the BATF), in the section related to prosecutions under 922(g)(8) for people possessing firearms while subject to a domestic violence restraining order, states:

This [exemption] applies to an officer’s possession of a firearm or ammunition whether on or off duty, as long as the officer’s official duties require the possession of the firearm or ammunition. On the other hand, Federal law would be violated if an officer subject to a disabling restraining order receives or possesses a firearm or ammunition in a personal capacity.

So a cop with a prior felony conviction and a prior involuntary mental health commitment who smokes weed and is subject to a domestic violence protection order with a court finding that they pose a credible threat to their partner’s safety, may, under federal law, still possess a firearm for “official duties.” A conviction for a misdemeanor crime of domestic violence does not fall under this exemption though.

Conclusion

The recent upswing in revolutionary antifascist organizing and militant street actions has so far resulted in surprisingly few federal arrests and prosecutions. We haven’t see the FBI informant/entrapment strategy at play around recent mobilizations the way we have in years past with cases like Eric McDavid and the Cleveland 4 and informants like Brandon Darby. The federal prosecutions we have seen recently—those at Standing Rock as well as Rakem’s and Dallas’—seem in many ways to be opportunistic more than premeditated. It’s impossible to know in the moment whether this marks a real shift in the federal repressive strategy, or whether it’s just a momentary blip as the FBI adjusts to the changing political terrain.

Nonetheless, fascist violence and organizing continues to escalate. In response, more and more people in radical movements are interested in at least understanding the operation and use of firearms for self-defense purposes. It’s critical that people who pursue this course of education and training understand the underlying legal issues so they can make informed choices about the potential risks they face. It’s even more important that people not accidentally expose other people to legal risks that they did not agree to take. It’s probably likely that we can expect to see more 922(g) cases, but the fewer opportunities we create for opportunistic federal prosecutions, the better.