Filed under: Analysis, Canada, Editorials, Featured, Immigration, Indigenous, Land, The State

“the spectre of an indigenous insurrection emerged during the Harper years. This is probably the largest threat to the Canadian state and it makes further investment in infrastructure look risky…”

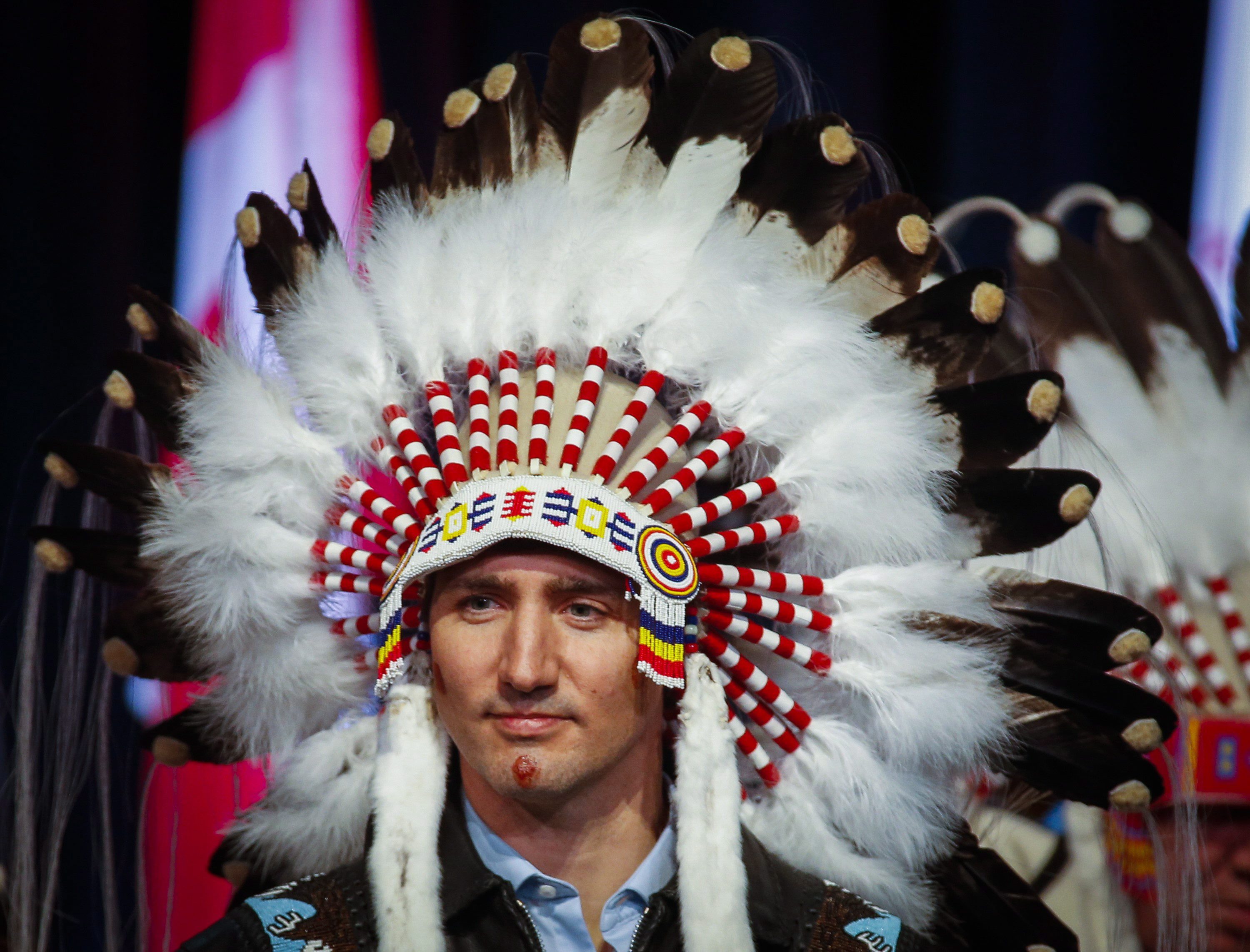

Like most people, I don’t pay much attention to Canadian politics. This is true even of those of us who live in the territory it controls. Especially these days, with an evil clown in charge of the United States government, the eyes of people in Canada are pretty fixed on the other side of the border. When people do bother to think about Canada, it’s usually to praise a political icon who has become an object of envy for progressives around the world — Justin Trudeau.

We take short breaks from watching the Trump circus to be vaguely relieved to see a handsome young man marching in the Pride parade, or being friends with refugees, or having his cabinet be half women.

But what the heck is Justin Trudeau? What role does he play in the ongoing capitalist, colonial project that is Canada? How does he relate to the ten years of conservative government that preceded him? And what does it mean to resist a state lead by a political figure like him?

Like I said, I don’t pay attention to Canada. But the way I see it, Canadian politics are defined by three factors: favourable comparison to the United States, resource extraction (aka colonial expansion), and the provincial/federal relationship. Let’s start by looking at the past couple of governments through this lens.

Trudeau’s Predecessors

To briefly consider the last two or three Canadian governments, for twelve years the Chretien/Martin Liberal party was built around neoliberal free trade policies. These deals opened up faster extraction of resources in Canada for a global market and unleashed Canadian extractive companies into every corner of the world. They balanced the federal budget while cutting social programs less that the Clinton government did during the same period and also avoided the Iraq war: this meant, to all of us with our eyes permanently fixed on the American spectacle, that Chretien didn’t seem that bad (even as folks threw down in the streets of Quebec city against the Free Trade Area of the Americas in 2001).

The Harper Conservative government was pushed to power by the same extractive industries that the Liberals had unleashed, notably the oil industry in Alberta’s Tar Sands, following a merger of the two right-leaning parties and the victory of their most conservative elements. He redefined the relationship between provinces and the federal government, reducing federal programs that were often then covered by provinces or replaced by tax cuts or payments. Harper largely reigned during the Obama years, which meant he didn’t have the important favourable comparison to the US working in his favour (though Canada did largely avoid the 2008 financial crisis, for which the Harper government took credit).

“Notably, this resistance prevented Tar Sands oil from reaching a port by pipeline – this was a major strategic win for the resistance and a serious blow to the credibility of the Harper government.”

During Harper’s ten year reign, there arose an increasingly powerful and well-organized resistance against him, led by indigenous nations across the country who organized on an impressive scale. This resistance was also characterized by increasing links between indigenous militants, who had built their skills with a string of land reclamations and the assertion of territorial autonomy during the previous decades, and settler anarchists and others on the anti-capitalist left.

Notably, this resistance prevented Tar Sands oil from reaching a port by pipeline – this was a major strategic win for the resistance and a serious blow to the credibility of the Harper government. The Canadian national identity as it has existed since the seventies is essentially opposed to Harper’s antagonistic politics, his stands on social issues, his militarism, nationalism, and racism — people were willing to ignore it for a while in the name of economic necessity, but it increasingly galvanized resistance as Harper pursued a more socially conservative agenda in his later years. Several provincial governments also shifted left during this time, notably BC, Alberta, and Ontario (slightly), partly in response to Harper’s downloading of programs, but also to recuperate popular anger.

Social Peace, for the Economy

Looking at these two recent governments helps us understand Trudeau’s mandate. The Harper government wasn’t able to take the expansion of resource extraction projects as far as it wanted to, because he wasn’t able to maintain the other two legs of the Canadian political stool: the pressure on the provinces from the retreat of the federal government and the appearance of being socially regressive relative to the US provoked too much opposition. At its base, Trudeau’s mandate then is to produce enough social peace for infrastructure expansion to become possible. It’s especially important for him to build this peace with indigenous nations, where resistance tends to be more committed, experienced, and able to act in critical areas far from cities (because Canada’s really big and me and most other anarchists live in a handful of large urban areas close to the border, far from these all-important extractive industries).

“Justin Trudeau is attempting to recreate this positive Canadian cultural identity to, on the one hand, pacify resistance to critical projects, and on the other, to to anchor a certain form of liberal (Liberal) politics…”

In spite of Harper’s token gestures of apologizing for residential schools and launching an inquiry, the spectre of an indigenous insurrection emerged during the Harper years. This is probably the largest threat to the Canadian state and it makes further investment in infrastructure look risky if the state can’t guarantee it can push projects through. Trudeau’s role is essentially counter-insurgency — divide, pacify, and undermine solidarity to isolate the elements of the resistance that will refuse to compromise, but who (he hopes) can be defeated.

It’s hard to exaggerate the level of goodwill Trudeau has enjoyed in Canada this past year as he put his program into effect. Above, I mentioned a Canadian national identity that was defined during the 1970s — well, this was largely done by Justin’s father, Pierre Elliot Trudeau, one of Canada’s most influential prime ministers. Justin Trudeau is attempting to recreate this positive Canadian cultural identity to, on the one hand, pacify resistance to critical projects, and on the other, to to anchor a certain form of liberal (Liberal) politics among the inhabitants of the Canadian territory, especially those who arrived in the country more recently.

The Invention of Canadian Identity

All nationalism is based on lies and imaginary narratives, but Canada’s is more transparent than most. Essentially, the Canadian national identity was created from nothing in the sixties and seventies. Canada didn’t have a flag before 1965, people sang God Save the Queen instead of Oh Canada up until 1980, there was no Canadian literature or music to speak of (there were regional musical forms, but the literary and cultural identity was mostly that of the British Commonwealth). Canada had fought unremarkably alongside England during the world wars, but didn’t have an independent foreign policy. And there’s no Canadian cuisine apart from a few things stolen from indigenous nations (maple syrup) and a few poverty dishes from Quebec (poutine).

“Canada” is an emptiness, an erasure. All the word “Canada” meant up until the mid sixties was a slow, methodical genocide against indigenous peoples and cultures and the exportation of resources. The project of Canada was nothing but that — and it still is nothing but that, though Pierre Trudeau and his immediate predecessor Lester B Pearson, also of the Liberal Party, made some efforts to pretty it up.

Prime Minister from 1968-1979, Trudeau 1 pumped lots of money into arts and culture, producing a generation of writers, musicians, and artists who, spread by an expanded state media apparatus, created an idea of what it meant to be Canadian. In this, he was able to rely on institutions like the National Film Board of Canada (which greatly expanded its operations in the late 60’s, extending the reach of official culture out from Canada’s centre) and the Canada Council For the Arts (which provided a huge boost in funding for artists producing Canada-themed content throughout the Trudeau years). The production of the new Canadian identity was still deeply tied to natural resources (think Gordon Lightfoot singing whistfully about the empty wild being opened up by the rail line), but framed as an appreciation of untouched natural beauty (canonization of the Group of Seven and Emily Carr).

“All nationalism is based on lies and imaginary narratives, but Canada’s is more transparent than most.”

At the time, these investments in culture were aimed at reducing regional discontent with a seemingly out-of-touch Ontario anglophone elite. The Official Languages Act of 1969 was the legislative cornerstone of a national identity based on two peoples, the French and the English, which sought to better integrate francophones, especially in Quebec, into the Canadian identity as the Quiet Revolution reached its peak. This was the carrot, while Trudeau also quickly showed he was also willing to use a stick, as the War Measures Act of 1970 aimed at Quebecois nationalists and communists shows, in the largest mass arrests in Canadian history until the 2010 G20 summit. At the same time, Trudeau 1 attempted to frame the Canadian identity he was producing as somehow “progressive” through his opposition to the Vietnam War, welcoming in thousands of US war resistors, building on Pearson’s rebranding of the Canadian military as a peacekeeper force, and also by pushing for a shift on ideas of race and immigration.

These were also the years when universal health care was established (introduced by Pearson, put into practice by Trudeau) and Employment Insurance (EI) and welfare income supports were massively expanded, all administered by the provinces with money from the federal government. These kinds of redistributive social policies are thus a big part of this version of the Canadian national identity, which means Harper’s challenges to universal health care (opening the door to private insurance) and the major cuts and underfunding to EI and income supports under the Chretien/Martin and Harper governments means there is an opportunity for Justin to be their champion.

This period in Quebec looked a little different and deserves its own analysis, which I won’t try to do here. The francophone cultural revival of this period emphasized a distinctly Quebecois identity, but it played on many of the same themes and values as in anglophone Canada and served a remarkbly similar function in building a sense of unity around colonial expansion.

And what about (im)migration?

In 1971, Pierre Trudeau also declared that Canada would adopt a multicultural policy, making it official that a part of the Canadian identity was to welcome other cultural practices in the territory without asking for assimilation to the reigning norm (though the Multiculturalism Act was not passed until 1988, many of its key policies were developed under Trudeau). Bilingualism and tolerance, both legally defined, remain important pieces of how Canada seeks to portray itself. During this period, Canada removed its ban on non-European immigration (late sixties) and by 1971 non-Europeans represented the majority of immigrants settling in Canada. However, they replaced the openly racist immigration policy with one more geared towards class – the point system. Canada’s geography gives it unique control over its borders and allows it to be very selective in its immigration. Canada, perhaps more than any other country, is built on courting the world’s upper classes to immigrate (a notable example being the billions of dollars brought by immigrants from Hong Kong in advance of the island’s reunification with China).

People considered less desirable are sometimes able to enter, but are often kept in long-term precarity through migrant worker and visa programs and purges (such as one against Roma people around 2012) are frequent. In 1978, the Trudeau government formally included acceptance of refugees in Canada’s immigration policy, and the image of Canada as a safe haven is another important piece of the positive Canadian identity. But this reputation as a refuge is greatly exaggerated – more than half of migrants are admitted on economic grounds, with then about another quarter being for family reunification. Only a slim section of Canada’s immigration allowance is for refugees, who are almost all carefully selected outside the country.

“in a context like Toronto’s, where more than half of people are born outside the country, the state clearly also has an interest in integrating new arrivals and the communities they form into this dominant Canadian identity.”

This selectiveness and the policy of multiculturalism have been invoked as reasons why Canada’s relationship to immigration is less conflictual than in countries like France and the US. But in a context like Toronto’s, where more than half of people are born outside the country, the state clearly also has an interest in integrating new arrivals and the communities they form into this dominant Canadian identity. In the past ten years, recent migrants, often new home owners in rapidly growing urban areas, have tended to vote against taxes and for conservative politicians, leading to phenomenons like Rob Ford and like the Federal Conservative Party carrying a majority of the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) in 2011. Harper was content to draw on their support while also stigmatizing migrants to get support from reactionaries.

Justin Trudeau has an interest then in re-asserting the positive, multi-cultural vision of Canada for reasons of party politics, but also to reduce the risk of regional tensions (GTA vs the rest of Southern Ontario; upsetting the linguistic power balance between French and English; etc) and to avoid an anti-immigrant movement that would threaten access to skilled workers and new capital coming from abroad. For all Pierre Trudeau’s rhetoric about how “uniformity is neither desirable nor possible,” the Canadian multicultural identity is simply a way for people to participate in their own way in the single-mindedly destructive capitalist and colonial project known as Canada. As Canada represents nothing but pillage, no cultural practice other than anti-authoritarian revolt can truly threaten it, so all governments since the 70s have continued Pierre Trudeau’s practice of funding and supporting “cultural” events in the name of the Canadian identity.

A Wave of Nostalgia

A major part of Trudeau’s charm comes from nostalgia for the kind of Canada he is selling: a return to peace-keeping (rather than the more bellicose posture of the Harper years); proud multiculturalism (after Harper’s “barbaric cultural practices” nonsense); socially progressive policies (especially relative to Trump); all trumpeted by made-in-Canada arts and culture that can stand up to the American cultural machine. This is the image of Canada that a large part of the generation that grew up in the 70’s still wants to be proud of.

It makes sense that people love health care, want to welcome immigrants, and are encouraged by progressive stands on social issues. These things aren’t the problem. The problem is that they are bundled together into a nationalistic project that causes us to see the Canadian state and economy as somehow benevolent and to let our guard down against their attacks.

“I don’t want the social peace Justin Trudeau offers, because social peace means business as usual — I want to fight for my autonomy and the autonomy of others on healthy land and water.”

By promoting a form of Canadian nationalism most developed by his father, Justin Trudeau is hoping to paper over the colonial nature of the Canadian project and the daily economic violence of capitalism. No less than Donald Trump, Trudeau is harkening back to a semi-imaginary past moment when there was less social conflict and nationalism could make us feel good. This form of nationalism is what allows Trudeau to assemble the three elements of Canadian politics: reducing popular anger allows resource extraction to proceed; progressive stands on social issues make Canada look good relative to the US; and reinvestment in social programs and infrastructure by a less debt-averse federal government reduces the burden on the provinces, which reduces conflict and makes it easier for the federal government to implement its agenda.

I’m not even in Canada, but it makes me sick to think about how Trudeau is making it ok to be proudly Canadian again. I don’t want to feel good about Canada. I don’t want to be either a pawn in its fuzzy colonial project or an excluded, banished from its gentrifying cities and productive workforce – I want to make the immense violence of the Canadian state and economy visible. I don’t want to fill the void that is Canada with flimsy little myths about how health care and multiculturalism mean we have nothing to be angry about – I want to look at the situation honestly and choose sides in the conflict. I don’t want the social peace Justin Trudeau offers, because social peace means business as usual — I want to fight for my autonomy and the autonomy of others on healthy land and water.

Rather than paint a maple leaf on your cheek for Canada 150, let’s take the opportunity to look the beast in the face. The sense of pride offered by nationalism is a false one and interferes with the real strength we can build together when we clearly identify our enemies and prepare to go on the offensive.