Filed under: Editorials, Insumisión, Mexico

Originally published to It’s Going Down

By Scott Campbell

It’s been several weeks since the last Insumisión. Apologies for the break, but now we’re back at it and as always there’s a lot of ground to cover. Before diving in, I’d like to share that in the next couple of months, an It’s Going Down contributor will be spending a chunk of time in Mexico with the goal of producing lots of original content. If you value the work we do here at IGD and would like to see it continue to grow, please consider contributing to the trip fundraiser or making a donation in general. We also recently published a call for translators to help put out even more content from Mexico. If you’re interested, get in touch! And now let’s take a look at the latest from Mexico…

Zapatistas for President?

Zapatistas at the opening of the Fifth National Indigenous Congress.

On October 11, 500 delegates from the National Indigenous Congress (CNI) and the military command of the Zapatistas (EZLN) met in San Cristóbal de las Casas, Chiapas to mark the 20th anniversary of the founding of the CNI. The opening comments from the Zapatistas were largely a call for indigenous peoples to get organized. It was the closing statement that caught everyone’s attention though. The CNI and EZLN announced they would begin consultations with their communities on the EZLN’s proposal of naming “an indigenous woman, a CNI delegate, as an independent candidate to the presidency of the country under the name of the National Indigenous Congress and the Zapatista Army for National Liberation in the electoral process of 2018.”

The reactions were immediate. Andrés Manuel López Obrador, the darling of the liberal electorate, was furious. He blames the Zapatistas for his losses in 2006 and 2012, and now they seem poised to interfere again with his presidential plans. Meanwhile, some anarchists pointed out that this proves the Zapatistas aren’t anarchists and that those who support the EZLN have been duped. Never mind that the EZLN has never claimed to be an anarchist group. On the authoritarian left, Mexico’s Socialist Workers Party could barely contain its glee over the news, emphatically endorsing the EZLN’s proposal.

El EZLN en 2006: era "el huevo de la serpiente". Luego, muy "radicales" han llamado a no votar y ahora postularán candidata independiente.

— Andrés Manuel (@lopezobrador_) October 16, 2016

The Zapatistas responded with a defensive and irritated statement largely arguing that this proposal is valid due to the impact it would have on the spectacle of electoral politics in laying bare the racism and sexism inherent in that process. A few days later, another statement communicated that the CNI and EZLN will announce the decision to run a candidate or not on January 1. They also said the “Zapatistas and ConSciences for Humanity” gathering will begin in Chiapas on December 25.

In reading and discussing these developments with compas in Mexico, the generally attitude seems to be to wait and see what happens. Some feel it is a publicity stunt, designed to provoke just the sort of reaction it did, and that this will be made clear on January 1. On the other hand, if a joint CNI-EZLN candidate is put forward, then a reevaluation by many anti-authoritarians would have to occur. While some of what they are proposing is interesting – to have an indigenous woman as president guided by the decisions of an assembly – to consider entering the electoral arena strikes many as a betrayal and is difficult to reconcile with the EZLN’s strident critiques of the system and power. To flirt with electoral politics even with the goal of détournement is to engage with a system fundamentally opposed to liberation, designed to consolidate power and legitimize repression. Such a move seems more akin to Michael Moore and his ficus plant than the Zapatistas and their uncompromising, decades-long struggle for autonomy and self-determination. Stay tuned.

In related news, a member of the CNI from the autonomous Tzeltal community of San Sebastián Bachajón was detained and severely beaten by a group led by a local government official. Two days later, on October 19, 800 police and 400 paramilitaries positioned themselves on the outskirts of that community. Fearing a raid, the alarm was sounded, but it appeared to just be an intimidation tactic. For other Chiapas news, be sure to check out Dorset Chiapas Solidarity’s Zapatista new summaries for September and October.

Refusing Fear in the Face of Femicide

Originating from an Argentinian call for a general women’s strike, on October 19 actions occurred all over Mexico to condemn the ongoing crisis of femicide in the country and the system that facilitates impunity in the face of the epidemic murders of cis and trans women. El Enemigo Común has a round-up of the events of that day and provides context on femicide in Mexico. “The State of Mexico registered 1,045 homicides of women between 2013 and 2015, out of a total of 6,488 women killed country-wide, according to government statistics. Next came Guerrero, Chihuahua, Mexico City, Jalisco and Oaxaca, with 512, 445, 402, 335 and 291 homicides of women reported, respectively, in the same period.” Those numbers a likely low, as it is estimated an average of six cis women are murdered in Mexico daily. The actions on October 19 were given additional urgency following the murder of Alessa Flores on October 13. Flores became the third trans woman to be murdered in Mexico in 13 days, and the 22nd to be killed in 2016.

A week later in Oaxaca, women organized a shutdown of a taxi stand following the sexual assault of a woman passenger by a taxi driver. “We’re very angry and outraged by the increase in sexual violence against women in Oaxaca, but above all by the impunity that reigns and continues to get worse,” an organizer said.

Femicide was also the focus of a Day of the Dead march in Mexico City on November 1. With their faces painted like Catrinas, hundreds of people marched through the city center. Said one of the marchers, “It felt very important for us to come out today to remember all the women killed by femicide in this country. Today we gather here as feminist women, brought together by the wave of femicides happening all over the country. We came out at this time of night because the streets are ours, the city is ours, the spaces are ours, and we came to prove it.”

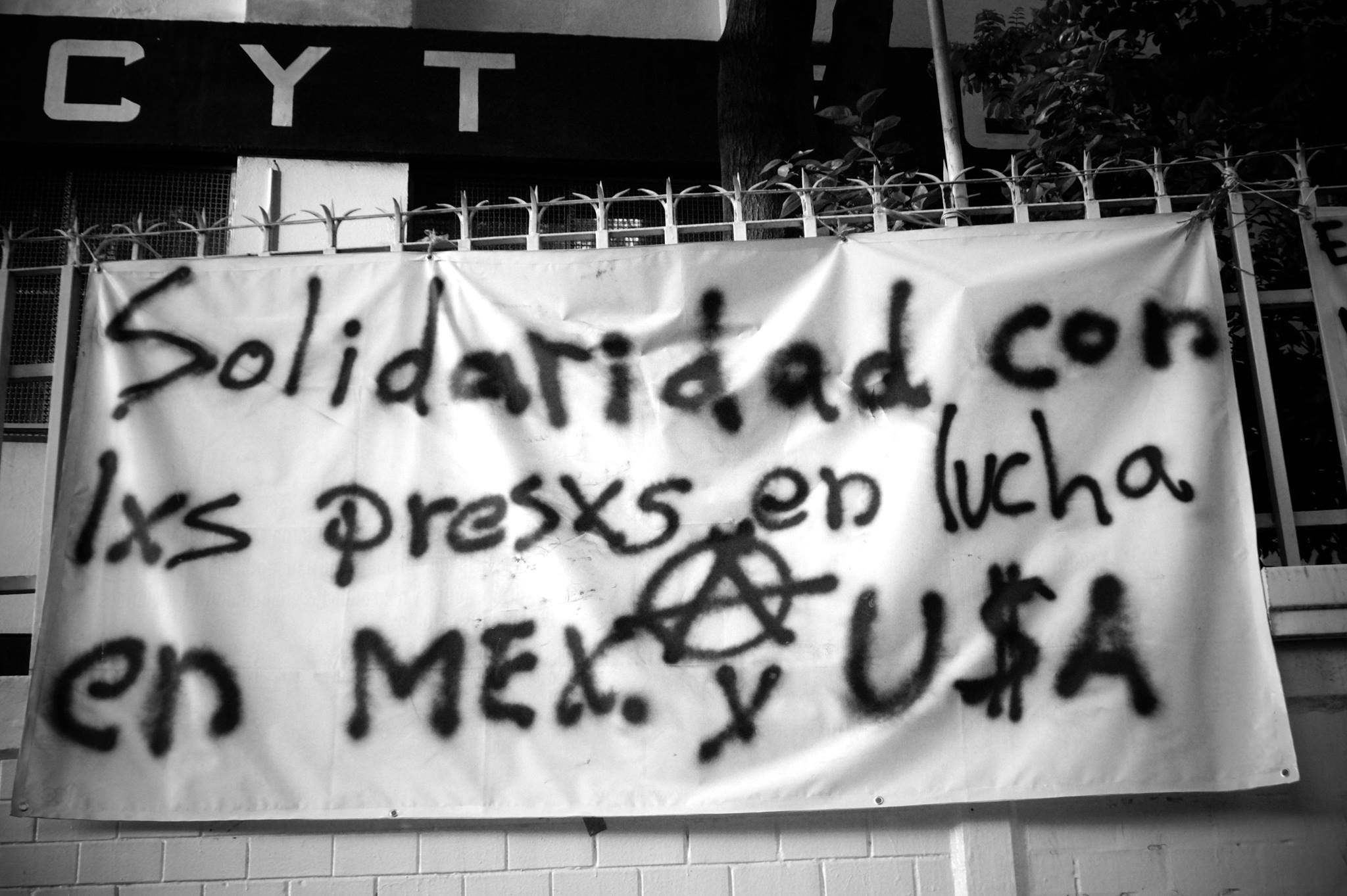

Prisoners in Resistance

On September 28, four anarchist prisoners in three different prisons began a hunger strike as an act of rebellion and in solidarity with the prison strike in the US. Throughout the strike, Luis Fernando Sotelo, Fernando Bárcenas and Miguel Peralta wrote various letters, all of which are translated on IGD. Out of concern for deteriorating health and permanent injury, the hunger strike ended after 15 days, though they continue to fast until 1pm each day.

Around the same time the strike ended, a push was underway by liberals in Mexico City to pass an amnesty law for the city’s political prisoners, specifically the anarchists. Instigated by the MORENA party of Andrés Manuel López Obrador, it was an attempt to divert attention from the anarchist prisoners’ strike toward electoral ends and was roundly rejected by the prisoners themselves. Fernando Bárcenas wrote, “We don’t need amnesties because we don’t want or need laws to govern our lives…We want to see the insurrection spread everywhere that destroys centralized power, the common yoke that all of us poor carry on our backs.” And Luis Fernando Sotelo responded with, “I do not want any institution to recognize my freedom if it means that freedom is partial, if not illusionary…I don’t want to be forgiven or redeemed by the machine that torments the people.”

Anarchists in Mexico City expressed their solidarity with the prisoners’ struggle by making it a focus of their annual combative march on October 2, marking the 1968 Tlatelolco massacre – which is distinct from the symbolic, state-facilitated commemorative march on the same day. They also called for militant actions for the following week at two of the Mexico City prisons holding the comrades.

The indigenous Nahua community of San Pedro Tlanixco in the State of Mexico is restarting efforts to fight for the freedom of several of its residents criminalized for their defense of the community’s water. Three are serving sentences of up to 54 years, while three others have been held in prison for ten years without being sentenced. Two more have arrest warrants out against them.

On October 12, hundreds marched in Chilpancingo, Guerrero calling for the release of all political prisoners, in particular the 13 members of the indigenous community police (CRAC-PC) who have been jailed for the past three years on weapons charges. A similar situation is unfolding in the autonomous indigenous Nahua community of Santa María Ostula in Michoacán, where three arrest warrants are out against the commander of their community police. At the same time, drug cartels are reorganizing and threatening the community, who successfully drove the cartels off their lands in 2009. The Zapatistas and National Indigenous Congress also released a statement in solidarity with Ostula.

Students Organizing

Students around Mexico continue organizing for a greater role in determining their own education, against state violence, and for access to education and to employment following graduation. As usual, it has been teaching college students (normalistas) who have been taking the lead. In Michoacán, where the state discriminates against hiring normalistas, students have been taking militant actions to demand jobs after they finish school, as well as to fight back against state repression. On September 27, 49 were arrested at a highway blockade in Tiripetío where state police also opened fire on them. In the days that followed, the students escalated their actions to demand freedom for their comrades by blockading train tracks with a burning truck, shutting down the town’s bus station, blockading the highway again, and detaining five police officers. Ultimately they were victorious, as by October 3, all 49 students were released, along with eight who had been imprisoned since August 15.

But events didn’t end there. On October 17, normalistas blockaded another highway, an action that was attacked with tear gas and rubber bullets by police and where 30 students, primarily women, were arrested. They were released shortly after. On October 22 and November 5, normalistas again attempted to blockade the train tracks that run near their school in Tiripetío, only to be repelled by police. Lastly in Michoacán, as of mid-October, aspiring students had occupied Michoacán University in the state capital of Morelia for 50 days, demanding the school accept and enroll more students and reduce application fees.

To the south in Guerrero, two normalistas from Ayotzinapa were murdered on October 4 while traveling on a bus back to the school from the state capital. Gunmen on board killed John Morales Hernández and Filemón Tacuba Castro and wounded three other passengers. The state is saying it was a robbery, though survivors indicate that the gunmen knew the two were Ayotzinapa students. In other Ayotzinapa news, the state announced on October 21 it had arrested Felipe Flores Vázquez, who was the local police chief of Iguala when the normalistas were attacked and disappeared there on September 26, 2014. The lawyers and parents of the normalistas are demanding the right to participate in the legal process against Flores, though the state has rejected this request. The government is playing up the arrest as a chance to learn what really happened that night, belying the fact that for the past two years it has actively worked to conceal the truth.

Since 2014, students at the National Polytechnic Institute (IPN) in Mexico City and an affiliated high school, the Scientific and Technological Studies Center 5 (CECyT 5), have been organizing and striking against cuts and attacks on education and pushing for the removal of the university’s director. CECyT 5 students have been on indefinite strike and their encampment was attacked by 40 to 60 porros (paid thugs) on October 7, leaving many students with serious injuries. In response, students installed barricades around campus, condemning not only the attacks and the administration, but expressing solidarity with anarchist prisoners on hunger strike in Mexico and with the prison strike in the US.

After the disappearance and murder of students and an alumnus of Veracruz University on September 29, students there organized a march against violence and impunity in the state, during which an Amnesty representative commented that “Veracruz has a human rights crisis like we’ve never seen before in the history of this state or in Mexico.” And in Chiapas, 28 normalistas also demanding work were arrested on November 5 and hit with federal charges. Fortunately, word spread quickly and people mobilized, leading to their release the next day.

#AlMomento

En estos momentos estan saliendo los estudiantes presos de #Chiapas. Gracias compas por todo el apoyo pic.twitter.com/UVjXYiWkGi— RadioZapote (@RadioZapote) November 7, 2016

Land Defense

Blockade of the Peñasquito gold mine in Zacatecas.

Actions in defense of the land continue around the country. In Acacoyagua, Chiapas, the municipality passed a declaration declaring it “mining free” and residents set up two blockades in early October to shut down the Casas Viejas titanium mine. Mining machinery was also set on fire. Around the same time in Zacatecas, twenty communities impacted by the Peñasquito mine, the largest gold mine in the state, blockaded all nine entrances to the mine. A few days later, police removed them from the main entrance, but the communities still held the eight other positions.

On October 22, the People’s Front in Defense of the Land (FPDT) in Atenco, State of Mexico, commemorated 15 years of existence. Formed to resist the construction of Mexico City’s new international airport on their lands, Atenco has come to symbolize militant self-determination and autonomy. “There were only two paths: to hand over the lands like merchandise and survive bent over, or to defend them with our lives if necessary. We decided to fight.” They defeated that attempt to build the airport, though are currently battling another. President Enrique Peña Nieto, who was formerly governor of the State of Mexico and whose police deployed severe violence against Atenco in 2006, including systematic sexual assault, the case of which is now before the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, is trying again for an airport. Despite work being ordered suspended by the courts, construction continues in Atenco. On October 5, gunmen opened fire on community members as they tried to halt the project.

Clashes between indigenous Yaqui communities left one dead and eight wounded on October 21. The conflict was instigated by Sempra Energy, a corporation based in San Diego, CA, who through their Mexican proxy company, IENova, is attempting to build a natural gas pipeline through Yaqui lands. One community, Lomas de Bacúm, has installed a blockade to stop the pipeline. They were attacked by communities who support the construction, likely due to the benefits promised if they let it be built on their lands. Following the violence, the Zapatistas and National Indigenous Congress released a statement in solidarity with the pipeline resistance and condemning the internal division and violence caused by the state and multinationals.

In Brief

Javier Duarte, the former governor of Veracruz who resigned on October 12, and Guillermo Padrés, the former governor of Sonora, are both on the run with warrants out for their arrests for corruption. Duarte fled in a state-owned helicopter, yet the government claims to not know where he is or how he got away. Priest and human rights defender Alejandro Solalinde indicated his likely location in Chiapas, but it has not been followed up on.

Quieren saber dónde está @Javier_Duarte ? Aquí las coordenadas. #VillaFlores #Chiapas #Chiapasionate pic.twitter.com/RmtYEByPQE

— Alejandro Solalinde (@padresolalinde) October 31, 2016

As many as 4,000 human bone fragments have been found on a five hectare site in Patrocinio, Coahuila. The state government says not to worry, they all belong to just three people. The group that searched the area begs to differ, as do the neighbors who said that SUVs drove into the site daily and huge fires were often seen burning on the land. PEMEX workers are organizing against the privatization of Mexico’s petroleum industry. A call has gone out among workers to fight back against firings and to take worker control of the Cangrejera plant in Veracruz to prevent its handover to private companies. There’s a good essay, translated into English, examining from a radical perspective the process of gentrification currently underway in Mexico City. In a recent example of that struggle, a group linked to the district government and escorted by police attacked and robbed vendors, who for 111 days had held an encampment in front of a Chedraui in Iztacalco, Mexico City. The vendors were protesting the opening of the big box chain store so close to their market.

That’s all the news for now. Insumisión will be back in about a month but keep an eye on IGD for more translations in the meantime.